Abstract

The article investigates characteristics of legal concepts as found in academic articles, focusing upon the knowledge base of legal experts. It is a cognitively oriented study of one of the semiotic basics of communication for academic legal purposes. The purpose is to study the structure of knowledge elements connected to the concept of “Criminal liability of corporations” from US law in and across individual experts in order to look for individual differences and similarities. The central concern is to investigate the conditions for the observable efficiency of semiosis in academic discourse. In a first basic section I discuss aspects relevant for a cognitively oriented study of academic discourse. The empirical part of the article consists of an analysis of text passages from two articles in American law journals. The results of the study support the assumption that high efficiency and precision of semiosis is due rather to the use of specific cognitive processing skills than to total identity of cognitive structures across individual experts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Roelcke [35, pp. 17–26] talks about approaches focusing upon the influential factors as subscribing to the context model of pragmalinguistics. Studies of this kind typically come from the fields of genre or discourse analysis.

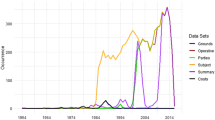

An interesting case of focusing on the communication of the group, but with interest in developments, is the work on detecting new terms and concepts in corpora by looking for words with a specifically high ‘weirdness factor’ [20].

Roelcke [35, pp. 17–26] sees such terminological approaches as adhering to the inventory model of system linguistics.

For more arguments in favour of memory as a (re-)constructive process, see [34].

Candlin [6, pp. 24–28] states that this means that specialised discourse is characterised by alterity rather than by intersubjectivity.

Concerning the distinction, see [33, p. 526].

Sowa [40] calls this type of semantic networks assertion oriented networks.

For a deeper discussion of the methodology, see [10].

I thank one of the anonymous reviewers for these suggestions.

References

Ahmad, K., and M.T. Musacchio. 2003. Enrico Fermi and the making of the language of nuclear physics. Fachsprache 25(3–4): 120–140.

Arntz, R., H. Picht, and F. Mayer. 2004. Einführung in die Terminologiearbeit. Hildesheim: Olms.

Bazerman, C. 1999. The languages of Edison’s light. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Becker, B.R. 1992. Corporate successor criminal liability: The real crime. American Journal of Criminal Law 19(3): 435–483.

Bucy, P.H. 1991. Corporate ethos: A standard for imposing corporate criminal liability. Minnesota Law Review 75(4): 1095–1184.

Candlin, C.N. 2002. Alterity, perspective and mutuality in LSP research and practice. In Conflict and negotiation in specialized texts, ed. M. Gotti, D. Heller, and M. Dossena, 20–40. Bern: Lang.

Christensen, R. 2005. Die Paradoxie richterlicher Gesetzgebung. In Recht verhandeln. Argumentieren, Begründen und Entscheiden im Diskurs des Rechts, ed. K.D. Lerch. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Dam, H.V., J. Engberg, and A. Schjoldager. 2005. Modelling semantic networks on source and target texts in consecutive interpreting: a contribution to the study of interpreters’ notes. In Knowledge and translation—Systemic approaches and methodological issues, ed. H.V. Dam, J. Engberg, and H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast, 227–254. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Engberg, J. 2008. Begriffsdynamik im Recht—Monitoring eines möglichen Verständlichkeitsproblems. In Profession & Kommunikation. Ausgewählte Beiträge zur GAL-Jahrestagung Koblenz 2005, ed. H. Diekmannshenke and S. Niemeier, 75–95. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

Engberg, J. 2009. Inhaltsvergleich von Gebrauchsanleitungen über Sprachgrenzen hinweg. In The instructive text, ed. M.G. Ditlevsen, P. Kastberg, and C. Pankow, in press. Tübingen: Narr.

Engelkamp, J. 1994. Episodisches Gedächtnis: Von Speichern zu Prozessen und Informationen. Psychologische Rundschau 45: 195–210.

Engelkamp, J. 2000. Fortschritte bei der Erforschung des episodischen Gedächtnisses. Zeitschrift für Psychologie 208: 91–109.

Fodor, J.A. 1975. The language of thought. New York: Crowell.

Fodor, J.A. 2001. The mind doesn’t work that way: The scope and limits of computational psychology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fodor, J.A., and E. Lepore. 1999. All at sea in semantic space: Churchland on meaning similarity. The Journal of Philosophy 96(8): 381–403.

Gerzymisch-Arbogast, H. 1994. Übersetzungswissenschaftliches Propädeutikum. Tübingen: Francke.

Gerzymisch-Arbogast, H. 1996. Termini im Kontext: Verfahren zur Erschließung und Übersetzung der textspezifischen Bedeutung von fachlichen Ausdrücken. Tübingen: Narr.

Gerzymisch-Arbogast, H. 1999. Kohärenz und Übersetzung: Wissenssysteme, ihre Repräsentation und Konkretisierung in Original und Übersetzung. In Wege der Übersetzungs- und Dolmetschforschung, ed. H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast, 77–106. Tübingen: Narr.

Gerzymisch-Arbogast, H., and K. Mudersbach. 1998. Methoden des wissenschaftlichen Übersetzens. Tübingen: Francke.

Gillam, L., and K. Ahmad. 2002. Sharing the knowledge of experts. Fachsprache 24(1/2): 2–19.

Hanauer, D.I. 2006. Scientific discourse. Multiliteracy in the classroom. London: Continuum.

Harder, P. 1999. Partial autonomy, ontology and methodology in cognitive linguistics. In Cognitive linguistics: Foundations, scope, and methodology, ed. T. Janssen, 195–222. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hodge, R., and G. Kress. 1988. Social semiotics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Horn, D. 1966. Rechtssprache und Kommunikation. Grundlegung einer semantischen Kommunikationstheorie. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Kuhn, T.S. 1970. The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Laurén, C. 2001. Fiktion und Wirklichkeit in einem schwedischen soziologischen Text. In Language for special purposes: Perspectives for the new millennium, ed. F. Mayer, 524–528. Tübingen: Narr.

McCabe, D.P., and D.A. Balota. 2007. Context effects on remembering and knowing: The expectancy heuristic. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory & Cognition 33(1): 536–549.

Millikan, R.G. 1998. A common structure for concepts of individuals, stuffs, and real kinds: More Mama, more milk, and more mouse. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 21: 55–100.

Mudersbach, K., and H. Gerzymisch-Arbogast. 1989. Isotopy and translation. In Translator and interpreter training and foreign language pedagogy, ed. P.W. Krawutschke, 147–170. New York: SUNY.

Müller, F. 1997. Rechtstext und Textarbeit in der Strukturierenden Rechtslehre. In Methodik, Theorie, Linguistik des Rechts. Neue Aufsätze (1995–1997), ed. R. Christensen, 71–92. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Nordman, M. 2001. Die Person hinter dem Text. Über die Soziologin Rita Liljeström. In Language for special purposes: Perspectives for the new millennium, ed. F. Mayer, 529–536. Tübingen: Narr.

Papafragou, A. 2002. Mindreading and verbal communication. Mind & Language 17(1–2): 55.

Premack, D., and G. Woodruff. 1978. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 4: 515–526.

Riegler, A. 2005. Constructive memory. Kybernetes 34(1): 89–104.

Roelcke, T. 1999. Fachsprachen. Berlin: Schmidt.

Roelcke, T. 2004. Stabilität statt Flexibilität? Kritische Anmerkungen zu den semantischen Grundlagen der modernen Terminologielehre. In Stabilität und Flexibilität in der Semantik, ed. I. Pohl, and K.-P. Konerding, 137–150. Frankfurt am Main: Lang.

Schroeder, T. 2007. A recipe for concept similarity. Mind & Language 22(1): 68–92.

Searle, J. 1995. The construction of social reality. New York: The Free Press.

Sinha, C. 1999. Grounding, mapping, and acts of meaning. In Cognitive linguistics: Foundations, scope, and methodology, ed. T. Janssen, 223–255. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Sowa, J.F. 2006. Semantic network. http://www.jfsowa.com/pubs/semnet.htm. Accessed 9 Sept 2009.

Sperber, D., and D. Wilson. 1988. Relevance—Communication and cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sperber, D., and D. Wilson. 2002. Pragmatics, modularity and mind-reading. Mind & Language 17(1–2): 3–23.

Temmerman, R. 2000. Towards new ways of terminology description. The sociocognitive approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Thibault, P.J. 2000. The dialogical integration of the brain in social semiosis: Edelman and the case for downward causation. Mind Culture and Activity 7(4): 291–311.

Tulving, E. 1972. Episodic and semantic memory. In Organization of memory, ed. E. Tulving, and W. Donaldson, 381–403. New York: Academic Press.

Tulving, E. 2002. Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review: Psychology 53: 1–25.

van Leeuwen, T. 2005. Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.

Wierzbicka, A. 1996. Semantics: Primes and universals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

The studies underlying this article have been partly undertaken during my visit as a research fellow at Brooklyn Law School, New York in February and March 2007. This visit was made possible by a grant from the Danish foundation Carlsbergfondet. I want to thank Prof. Larry Solan and Rachel Ehrhardt for invaluable help with these studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Engberg, J. Individual Conceptual Structure and Legal Experts’ Efficient Communication. Int J Semiot Law 22, 223–243 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-009-9104-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-009-9104-x