Abstract

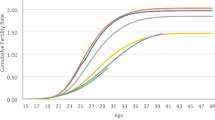

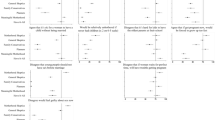

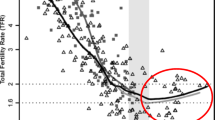

Second demographic transition (SDT) theory posits that increased individualism and secularization have contributed to low fertility in Europe, but very little work has directly tested the salience of SDT theory to fertility trends in the US. Using longitudinal data from a nationally representative cohort of women who were followed throughout their reproductive years (National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 cohort, NLSY79), this study examines the role of several key indicators of the SDT (secularization, egalitarianism, religious affiliation, and female participation in the labor market) on fertility behavior over time (1982–2006). Analyses employ Poisson estimation, logistic regression, and cross-lagged structural equation models to observe unidirectional and bidirectional relationships over the reproductive life course. Findings lend support to the relevance of SDT theory in the US but also provide evidence of “American bipolarity” which distinguishes the US from the European case. Furthermore, analyses document the reciprocal nature of these relationships over time which has implications for how we understand these associations at the individual-level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In one case, completed fertility behavior is measured using a different specification: the total number of children ever born by 2006 (range = 0–11, mean = 1.83, standard deviation = 1.41). (See Poisson models presented in Table 3.).

Women who were unemployed or out of the labor market received a value on this variable corresponding with the mean number of hours worked among employed women in the sample in a given year. This allows for a straightforward interpretation of the effect of the number of hours worked net of employment status, since point estimates in regression models indicate the effect of an independent variable on the dependent variable, net of all other covariates in the model. This logic is similar to calculating a predicted probability as a value of x changes, when all other values on the right side of the equation are held constant at their mean value. Thus, the point estimates from subsequent regression models can be interpreted as the effect of being employed, and the effect of the number of hours worked net of employment status.

Similar to hours worked, unemployed women were assigned the mean level of job satisfaction for employed women in that year. This point estimate from subsequent regression equations can be interpreted as the effect of job satisfaction net of employment status.

Consistent with the coding strategy for women’s participation in the labor market, women who remained childless by the 2006 interview were assigned the mean value of both indicators among mothers in the sample.

Although Moors (2003, 2008) advocates for the use of latent class analysis to determine attitude profiles for the prediction of fertility behavior, these data do not include a sufficient number of variables within each domain to adequately produce such profiles. Instead, this analysis utilizes sparser but broader data to examine the impact of SDT indicators on multiple parity progressions over time to determine a similar profile.

Mplus provides superior estimation of models including ordered or dichotomous dependent variables. Other programs geared towards structural equation modeling such as AMOS use algorithms which assume all dependent variables are continuous measures. Additionally, two goodness-of-fit statistics are provided for each model. Since the sample size is somewhat large, the χ2 statistic (which compares the observed and predicted covariances, testing the null hypothesis that the model fits the data perfectly) fails to provide the best measure of model fit. Instead, I draw upon the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) which performs well for large sample sizes and adjusts for model complexity. This statistic compares model fit between the given model and the independence model, and tends to range between 0 and 1 with higher scores conferring better model fit. Scores of 0.90 are required to accept the model as a good fit for the data. I also reference the root means square error of approximation (RMSEA) which adjusts for error in the population, thus making it ideal for use with large population-level samples. Scores less than 0.05 indicate adequate approximation (Curran et al. 2003).

References

Barber, J. S. (2001). The intergenerational transmission of age at first birth among married and unmarried men and women. Social Science Research, 30, 219–247.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. In G. B. Roberts (Ed.), Demographic and economic change in developed countries (pp. 209–240). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1991). Treatise on the family. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bhrolchain, M. N. (1992). Period paramount? A critique of the cohort approach to fertility. Population and Development Review, 18(4), 599–629.

Bielby, W. T., & Hauser, R. M. (1977). Structural equation models. Annual Review of Sociology, 3, 137–161.

Bumpass, L. L. (1990). What’s happening to the family? Interactions between demographic and institutional change. Demography, 27(November), 483–498.

Caldwell, J. C. (2001). The globalization of fertility behavior. Population and Development Review, 27(Supplement), 93–115.

Casterline, J. B. (2001). The pace of fertility transition: National patterns in the second half of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review, 27(Supplement), 17–52.

Cleland, J., & Wilson, C. (1987). Demand theories of the fertility transition: An iconoclastic view. Population Studies, 41(1), 5–30.

Cunningham, M., Beutel, A. M., Barber, J. S., & Thornton, A. (2005). Reciprocal relationships between attitudes about gender and social contexts during young adulthood. Social Science Research, 34(4), 862–892.

Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., Chen, F., Paxton, P., & Kirby, J. B. (2003). Finite sampling properties of the point estimates and confidence intervals of the RMSEA. Sociological Methods and Research, 32, 208–252.

Forste, R., & Tienda, M. (1996). What’s behind racial and ethnic fertility differentials? Population and Development Review, 22(Supplement), 109–150.

Guzzo, K. B., & Furstenberg, F. F., Jr. (2007). Multipartnered fertility among young women with a nonmarital first birth: Prevalence and risk factors. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39, 29–38.

Hayford, S. R., & Morgan, S. P. (2008). Religiosity and fertility in the United States: The role of fertility intentions. Social Forces, 86(3), 1163–1185.

Hofferth, S. L. (1987). The social and economic consequences of teenage childbearing. In C. Hayes & S. L. Hofferth (Eds.), Risking the future: Adolescent sexuality, pregnancy, and childbearing (Vol. II, pp. 123–144). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Hoffman, S. D., & Maynard, R. A. (2008). Kids Having Kids: Economic costs and social consequences of teen pregnancy (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Kent, M., & Mather, M. (2002). What drives US population growth? Population Bulletin, 57(4), 1–43.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1983). A century of demographic and cultural change in Western Europe: An exploration of underlying dimensions. Population and Development Review, 9(3), 411–435.

Lesthaeghe, R. (1998). On theory development: Applications to the study of family formation. Population and Development Review, 24(1), 1–14.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211–251.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Neels, K. (2002). From the first to the second demographic transition: An interpretation of the spatial continuity of demographic innovation in France, Belgium and Switzerland. European Journal of Population, 18, 325–360.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Neidert, L. (2006). The second demographic transition in the United States: Exception or textbook example? Population and Development Review, 32(4), 669–698.

Lesthaeghe, R., & Surkyn, J. (1988). Cultural dynamics and economic theories of fertility change. Population and Development Review, 14(1), 1–45.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Sutton, P. D., Ventura, S. J., Menacker, F., & Kirmeyer, S. (2006). Births: Final data for 2004. National Vital Statistics Report, 55(1), 1–102.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627.

McQuillan, K. (2004). When does religion influence fertility? Population and Development Review, 30(1), 25–56.

Moors, G. (2003). Estimating the reciprocal effect of gender role attitudes and family formation: A log-linear path model with latent variables. European Journal of Population, 19, 199–221.

Moors, G. (2008). The valued child: In search of a latent attitude profile that influences the transition to motherhood. European Journal of Population, 24, 33–57.

Morgan, S. P. (2003). Is low fertility a twenty-first-century demographic crisis? Demography, 40(4), 589–603.

Morgan, S. P., & Rackin, H. (2010). The correspondence between fertility intentions and behavior in the United States. Population and Development Review, 36(1), 91–118.

Morgan, S. P., & Rindfuss, R. R. (1999). Reexamining the link of early childbearing to marriage and subsequent fertility. Demography, 36, 59–75.

Morgan, S. P., & Taylor, M. G. (2006). Low fertility at the turn of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 375–399.

Mosher, W. D., & Bachrach, C. A. (1996). Understanding U.S. fertility: Continuity and change in the National Survey of Family Growth, 1988–1995. Family Planning Perspectives, 28, 4–12.

Mosher, W. D., Williams, L. B., & Johnson, D. P. (1992). Religion and fertility in the United States: New patterns. Demography, 29(2), 199–214.

Musick, K., England, P., Edgington, S., & Kangas, N. (2009). Education differences in intended and unintended fertility. Social Forces, 88(2), 543–572.

Mustillo, S., Landerman, L. R., & Land, K. C. (2012). Modeling longitudinal count data: Testing for group differences in growth trajectories using average marginal effects. Sociological Methods and Research, 41(3), 467–487.

NLSY79 User’s Guide: A guide to the 1979–2006 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth Data. (2008). Available via http://www.nlsinfo.org/nlsy79/docs/79html/79text/front.htm. Cited 1 March 2010.

Ogden, P. E., & Hall, R. (2004). The second demographic transition, new household forms and the urban population of France during the 1990’s. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 29(1), 88–105.

Preston, S. (1987). Changing values and falling birth rates. Population and Development Review, S12, S176–S195.

Population Reference Bureau. (2009). 2007 World Population Data Sheet. Retrieved March 1, 2010, from www.prb.org.

Quesnel-Vallée, A., & Morgan, S. P. (2003). Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review, 22(5–6), 497–525.

Reher, D. S. (2007). Towards long-term population decline: A discussion of relevant issues. European Journal of Population, 23, 189–207.

Robinson, W. C. (1997). The economic theory of fertility over three decades. Population Studies, 51, 63–74.

Smock, P. (2000). Cohabitation in the United States: An appraisal of research themes, findings and implications. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 1–20.

Surkyn, J., & Lesthaeghe, R. (2004). Value orientations and the second demographic transition (SDT) in Northern, Western and Southern Europe: An update. Demographic Research, Special Collection 3, Article 3, 45–86.

van de Kaa, D. J. (1987). Europe’s second demographic transition. Population Bulletin, 42(1), 1–57.

Ventura, S. J., Bachrach, C. A., Hill, L., Kaye, K., Holcomb, P., & Koff, E. (1995). The demography of out-of-wedlock childbearing. In U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Report to Congress on Out-of-Wedlock Childbearing (pp. 1–80). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Westoff, C. F., & Jones, E. F. (1979). The end of ‘Catholic’ fertility. Demography, 16(2), 209–217.

Westoff, C. F., & Marshall, E. A. (2010). Hispanic fertility, religion and religiousness in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review, 29(4), 441–452.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Paul Amato, Alan Booth, and Nancy Landale for helpful comments on earlier drafts. Support for this work was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Interdisciplinary Training in Demography (Grant No. T32 HD007514, PI: Gordon DeJong) to the Pennsylvania State University Population Research Institute. Opinions reflect those of the author and not necessarily those of the granting agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kane, J.B. A Closer Look at the Second Demographic Transition in the US: Evidence of Bidirectionality from a Cohort Perspective (1982–2006). Popul Res Policy Rev 32, 47–80 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9257-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-012-9257-2