Abstract

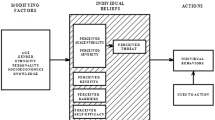

Hispanic women’s cervical cancer rates are disproportionately high. The Health Belief Model (HBM) was used as a theoretical framework to explore beliefs, attitudes, socio-economic, and cultural factors influencing Hispanic women’s decisions about cervical cancer screening. A cross-sectional survey was conducted among Hispanic women 18–65 years old (n = 205) in the Upstate of South Carolina. Generalized Linear Modeling was used. Across all models, perceived threats (susceptibility and severity), self-efficacy, and the interaction of benefits and barriers were significant predictors. Significant covariates included age, marital status, income, regular medical care, and familism. A modified HBM was a useful model for examining cervical cancer screening in this sample of Hispanic women. The inclusion of external, or social factors increased the strength of the HBM as an explanatory model. The HBM can be used as a framework to design culturally appropriate cervical cancer screening interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2009. Atlanta, GA, 2009. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/500809webpdf.pdf.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: recommendations and rationale. Rockville, MD: USPSTF Program Office; 2012. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/3rduspstf/cervcan/cervcanrr.htm.

National Cancer Policy Board, IOM. Fulfilling the potential of cancer prevention and early detection. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer screening. US Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(51):1038–42.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020 topics and objectives: cancer. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=5.

White K, Garces IC, Bandura L, et al. Design and evaluation of a theory-based, culturally relevant outreach model for breast and cervical cancer screening for Latina immigrants. Ethn Dis. 2012;22(3):274–80.

American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer. Prevention and early detection. Atlanta, GA, 2013. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003167-pdf.pdf.

Peirson L, Fitzpatrick-Lewis D, Ciliska D, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2013;2(35):1–14.

Meissner BN, Taubman ML, et al. Which women aren’t getting mammograms and why? (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(1):61–70.

Erwin DO, Treviño M, Saad-Harfouche FG, et al. Contextualizing diversity and culture within cancer control interventions for Latinas: changing interventions, not cultures. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(4):693–701.

Beach ML, Flood AB, Robinson CM, et al. Can language-concordant preventive care managers improve cancer screening rates? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2007;16(10):2058–64.

Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control. Health United States, 2012. Washington DC: DHHS Publication No. 2013-1232.2013, 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus12.pdf.

Parra-Medina D, Hilfinger DK, Fore E, et al. The partnership for cancer prevention: addressing access to cervical cancer screening among Latinas in South Carolina. JSC Med Assoc. 2009;105(7):297–305.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2012. Atlanta, GA, 2012. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-033423.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cervical cancer rates by race and ethnicity. Atlanta, GA, 2012. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/statistics/race.htm.

Arredondo EM, Pollak K, Costanzo PR, et al. Evaluating a stage model in predicting monolingual Spanish-speaking Latinas’ cervical cancer screening practices: the role of psychosocial and cultural predictors. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35(6):791–805.

Abraido-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Gammon MD. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Latinas and non-Latina Whites. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1393–98.

Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The health belief model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health behavior and health education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. p. 45–66.

Ben-Natan M, Adir O. Screening for cervical cancer among Israeli lesbian women. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56:433–41.

Lopez R, McMahan S. College women’s perception and knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. Calif J Health Promot. 2007;5(3):12–25.

Montgomery K, Bloch JR, Bhattacharya A, et al. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer knowledge, health beliefs, and preventative practices in older women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;39(3):238–49.

Tracy JK, Lydecker AD, Ireland L. Barriers to cervical cancer screening among lesbians. J Womens Health Issues Care. 2010;19(2):229–37.

Urrutia MT, Hall R. Beliefs about cervical cancer and Pap test: a new Chilean questionnaire. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2013;45(2):126–31.

Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:328–35.

Rosentock IM, et al. Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(2):175–83.

Palmer R, Fernandez ME, Tortolero-Luna G, et al. Acculturation and mammography screening among Hispanic women living in farmworker communities. Cancer Control. 2005;12:21–7.

Ramirez AG, Suarez L, McAlister A, et al. Cervical cancer screening in regional Hispanic populations. Am J Health Behav. 2000;24(3):181–92.

Sussner KM, Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, et al. Acculturation and familiarity with, attitudes towards and beliefs about genetic testing for cancer risk within Latinas in East Harlem, New York City. J Genet Couns. 2009;18(1):60–71.

Rosenstock IM. Why people use health services. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3):94–121.

Hayden J. Introduction to health behavior theory. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2009.

Vadaparampil ST, Champion VL, Miller TK, et al. Using the health belief model to examine differences in adherence to mammography among African-American and Caucasian women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2003;2(4):59–78.

Clark NM, Becker MH. Theoretical models and strategies for improving adherence and disease management. In: Shumaker SS, et al., editors. The handbook of health behavior change. New York, NY: Springer; 1998. p. 5–33.

Johnson CE, Mues KE, Mayne SL, et al. Cervical cancer screening among immigrants and ethnic minorities: a systematic review using the health belief model. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2008;12(3):232–41.

Espinosa de los Monteros K, Gallo LC. The relevance of fatalism in the study of Latinas’ cancer screening behavior: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Med. 2011;18(4):310–8.

Boyer LE, Williams M, Calker LC, et al. Hispanic women’s perceptions regarding cervical cancer screening. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2000;30:240–5.

Erwin DO, Treviño M, Saad-Harfouche FG, et al. Contextualizing diversity and culture within cancer control interventions for Latinas: changing interventions, not cultures. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:693–701.

Siatkowski A. Hispanic acculturation: a concept analysis. J Transcult Nurs. 2007;18(4):316–23.

Wu ZH, Black SA, Markides KS. Prevalence and associated factors of cancer screening: why are so many older Mexican American women never screened? Prev Med. 2001;33:268–73.

Marín G, Marín BVO. Research with Hispanic populations. Applied social research methods series. California: Sage; 1991. p. 23.

Sabogal F, Marín G, Otero-Sabogal R, et al. Hispanic familism and acculturation: what changes and what doesn’t? Hisp J Behav Sci. 1987;9(4):397–412.

Gaines S, Marelich W, Bledsoe K, et al. Links between race/ethnicity and cultural values as mediated by racial/ethnic identity and moderated by gender. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72:1460–76.

Abraido-Lanza AF, Viladrich A, Florez KR, et al. Fatalismo reconsidered: a cautionary note for health-related research and practice with Latino populations. Ethn Dis. 2003;17:153–8.

Antshel KM. Integrating culture as a means of improving treatment adherence in the Latino population. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7(4):435–49.

Powe BD, Finnie R. Cancer fatalism: the state of the science. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(6):454–65.

Scarinci IC, Beech BM, Kovach KW, et al. An examination of sociocultural factors associated with cervical cancer screening among low-income Latina immigrants of reproductive age. J Immigr Health. 2003;5(3):119–28.

Byrd TL, et al. Cervical cancer screening beliefs among young Hispanic women. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):192–7.

Fulton J, et al. Determinants of breast cancer screening among inner-city Hispanic women in comparison with other inner-city women. Public Health Rep. 1995;110(4):476–82.

Mandelblatt JS, et al. Breast and cervix cancer screening among multiethnic women: role of age, health, and source of care. Prev Med. 1999;28:418–25.

Urrutia MT. Development and testing of a questionnaire: beliefs about cervical cancer and Pap test in Chilean women. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami; 2009.

Bracken BA, Barona A. State of the art procedures for translating, validating and using psychoeducational tests in cross-cultural assessment. Sch Psychol Int. 1991;12(1–2):119–32.

Marín G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: the bidimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hisp J Behav Sci. 1996;18:297–316.

Lugo-Steidel AG, Contreras JM. A new familism scale for use with Latino populations. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2003;25(3):312–30.

Lopez-McKee G, et al. Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of the Powe fatalism inventory. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2007;39(1):68–70.

Watts L, et al. Understanding barriers to cervical cancer screening among Hispanic women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(2):199.e1–8.

Ries LA, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2005. Bethesda, MD, 2008. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2005/.

Allahverdipour H, Emami A. Perceptions of cervical cancer threat, benefits, and barriers of papanicolaou smear screening programs for women in Iran. Women Health. 2008;47(3):23–37.

Parra-Medina D, et al. The partnership for cancer prevention: addressing access to cervical cancer screening among Latinas in South Carolina. JSC Med Assoc. 2009;105(7):297–305.

Fernandez-Esquer ME, Espinoza P, Torres I, et al. A su salud: a quasi-experimental study among Mexican American women. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27(5):536–45.

Bazargan M, Bazargan SH, Farooq M, et al. Correlates of cervical cancer screening among underserved Hispanic and African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;39(3):465–73.

Owusu GA, Brown S, Cready CM, et al. Race and ethnic disparities in cervical cancer screening in a safety-net system. Matern Child Health J. 2005;9(3):285–95.

Suarez L. Pap smear and mammogram screening in Mexican-American women: the effects of acculturation. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(5):742–6.

Marin G, Triandis HC. Allocentrism as an important characteristic of the behavior of Latin Americans and Hispanics. In: Diaz-Guerrero R, editor. Cross-cultural and national studies of social psychology. Amsterdam: North Holland; 1985.

Kreuter MW, Lezin N. Social capital theory: implications for community-based health promotion. In: Clemente D, Crosby RA, Kegler MC, editors. Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research: strategies for improving public health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moore de Peralta, A., Holaday, B. & McDonell, J.R. Factors Affecting Hispanic Women’s Participation in Screening for Cervical Cancer. J Immigrant Minority Health 17, 684–695 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-9997-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-9997-7