Abstract

In this paper, we examine herding across asset classes and industry levels. We also study what incentives managers at various layers of the financial industry face when investing. To do so, we use unique and detailed monthly portfolios between 1996 and 2005 from pension funds in Chile, a pioneer in pension-fund reform. The results show that pension funds herd more in assets that have more risk and for which pension funds have less market information. Furthermore, the results show that herding is more prevalent for funds that narrowly compete with each other, namely, when comparing funds of the same type across pension fund administrators (PFAs). There is much less herding across PFAs as a whole and in individual pension funds within PFAs. These herding patterns are consistent with incentives for managers to be close to industry benchmarks, and might be also driven by market forces and partly by regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Many papers in the literature focus on equity mutual funds, whose portfolio data are mostly available publicly, and study their investment patterns (e.g., Grinblatt et al. 1995; Wermers 1999; Kacperczyk et al. 2005). Others analyze general data on institutional investors (e.g., Sias and Starks 1997; Nofsinger and Sias 1999; Grinblatt and Keloharju 2000; Sias 2004; Choi and Sias 2009).

The few studies available on pension funds typically use quarterly data for a subsample of the funds and focus almost exclusively on equity holdings. Lakonishok et al. (1992), Badrinath and Wahal (2002), and Ferson and Khang (2002) analyze US data. Blake et al. (2002) and Voronkova and Bohl (2005) use data from the UK and Poland, respectively. Langford et al. (2006) use return data to study Australia’s superannuation funds.

The original data also contain information on the holdings of derivatives, investment and mutual fund quotas, former pension system bonds, deposits, and foreign assets, but we exclude them from the analysis for various reasons. For instance, former pension system bonds are securities that were issued to the workers that moved from the old pay-as-you-go system to the new pension system when the reform was implemented in 1981. Thus, they are highly idiosyncratic and are increasingly disappearing as the system matures. Also, while quotas of investment and mutual funds are variable income instruments, the underlying assets are in many cases fixed income (bond funds) or a combination of bonds and equity, so they cannot be easily mapped into the standard categories. Foreign assets are excluded because, for regulatory reasons, most foreign investment carried out by Chilean pension funds occurs through the purchase of quotas of foreign investment funds.

While mortgage bonds (letras hipotecarias) represent 73.3 % of the observations, they only stand for 19.6 % of the investment when considering the entire period 1996–2005.

In this table, corporate bonds and financial institutions bonds are grouped together for data availability reasons.

The median amounts per issue are smaller for corporate bonds than for equity because companies typically issue several series of a corporate bond. Median amounts per issue for government bonds are small because the government tries to issue regularly to provide liquidity to the market and establish the benchmark yield curve. However, this should not make each issuance less transparent because the underlying debtor is the same. Summary statistics on amounts per issue are not reported but are available upon request.

Data on the trading frequency of corporate and government bonds come from Lazen (2005). Trading frequency for equities come from the Santiago Stock Exchange.

Infrequent trading does not necessarily mean that PFAs do not actively change the relative composition of their portfolios because, even if most assets are not traded, their relative importance depends on the changes experienced by those that are active.

The turnover measures described above are useful to determine the extent to which PFAs rebalance their portfolios, but they do not appropriately capture the extent to which that rebalancing is passive or active. In other words, part of the turnover might just be the consequence of passive trading due to: (i) the constant net inflows PFAs receive from current contributors that have not yet retired, or (ii) outflows due to pensioners retiring and leaving the system. Passive trading might also occur because some assets mature and, in order to reinvest them, PFAs need to purchase new instruments. Therefore, the amount of active turnover and the number of managers willing to change positions over time to maximize returns is lower than the turnover measures reported above.

Some papers propose that financial-institution bonds are more opaque than standard corporate bonds (Morgan 2002). However, others have shown that large banks are not more opaque than comparable corporations (Flannery et al. 2004). In Chile, only large banks issue corporate bonds, so in principle there is not a large difference in opacity between these two asset classes.

During 1996–1999, pension funds administrators offered a single fund (corresponding to Fund C in the current classification), and during 2000–2002 they offered two funds (corresponding to Funds C and D in the current classification).

The working paper version of this paper, Raddatz and Schmukler (2011), shows the buy and sell decomposition at the PFA level as well.

These results might slightly overestimate the role of purchases at issuance. The reason is that we do not have the issuance date for the fixed-income assets, so we assume that it corresponds to the date when the assets first appear in our data set. This is a good approximation because PFAs tend to quickly absorb fixed-income assets in their portfolio. According to market participants, PFAs actively demand assets during the underwriting process. However, it is possible that, in a few cases, we might exclude the first purchase of an asset in secondary markets.

The reason Sias (2004) standardizes the statistics is that it conducts inference on β t based on the time-variation of the parameters only (à la Fama and MacBeth 1973), and the standardization of the variables controls for changes in their mean and variance over time. Sias’ approach is reasonable but cannot be directly applied to the Chilean data because Chilean PFAs trade infrequently and a large fraction of the assets that are active in a month are not traded in the following one. This means that the sample over which the regressions in equation (2) can be estimated (i.e. the sample of assets traded in two consecutive periods) is different from the sample of traded assets in each period. Moreover, the mean and variance of the standardized statistics are different from zero and one, respectively, in the regression sample. Since the regression sample changes over time, the correct standardization in our case is time varying. We achieve this time-varying standardization by estimating the regressions of the raw fractions (Raw i,t ) including a constant (to remove the mean of the dependent and independent variable) and then correcting the estimated coefficients, multiplying them by the ratio of the standard deviation of the dependent to the independent variable in each regression sample.

The idea is that funds investing in riskier assets will have a higher degree of idiosyncratic volatility if they do not follow the herd, making them more likely to hit the regulatory band. On the other hand, if they always follow the crowd, all risk in their portfolios would be aggregate risk. So, even if their absolute returns are volatile, their relative returns are not.

For a discussion, see Bodie (1990), Piñera (1991), Davis (1995), Vittas (1999), Arrau and Chumacero (1998), Zurita (1999), Catalán et al. (2000), Impavido and Musalem (2000), Lefort and Walker (2002a, b), Blommestein (2001), Davis and Steil (2001), Corbo and Schmidt-Hebbel (2003), Impavido et al. (2003), Catalán (2004), Olivares (2005), Yermo (2005), Berstein and Chumacero (2006), de la Torre and Schmukler (2006), Andrade et al. (2007), The Economist (2008), and Raddatz and Schmukler (2011).

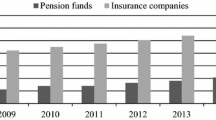

Moreover, pension funds invest heavily short term. Opazo et al. (2009) show that Chilean pension fund portfolios are short term relative to those of insurance companies and US mutual funds.

References

Amihud Y, Mendelson H (1986) Asset pricing and the bid-ask spread. J Financ Econ 17(2):223–249

Andrade L, Farrell D, Lund S (2007) Fulfilling the potential of Latin America’s financial systems. McKinsey Quarterly

Arrau P, Chumacero R (1998) Tamaño de los fondos de pensiones en Chile y su desempeño financiero. Cuad Econ 35(105):205–235

Badrinath SG, Wahal S (2002) Momentum trading by institutions. J Finance 57(6):2449–2478

Banerjee AV (1992) A simple model of herd behavior. Quar J Econ 107(3):797–817

Bekaert G, Harvey CR, Lundblad C (2007) Liquidity and expected returns: lessons from emerging markets. Rev Financ Stud 20(6):1783–1831

Berstein SM, Chumacero R (2006) Quantifying the costs of investment limits for Chilean pension funds. Fisc Stud 27(1):99–123

Bessembinder H, Maxwell W (2008) Transparency and the corporate bonds market. J Econ Perspect 22(2):217–234

Bikhchandani S, Hirshleifer D, Welch I (1992) A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change in informational cascades. J Pol Econ 100(5):992–1026

Blake D, Lehmann B, Timmermann A (2002) Performance clustering and incentives in the UK pension fund industry. J Asset Manag 3(2):173–194

Blommestein H (2001) Ageing, pension reform, and financial market implications in the OECD area. CeRP Working paper 9/01

Bodie Z (1990) Managing pension funds and retirement assets: an international perspective. J Financ Serv Res 4(4):419–460

Bolton P, Scheinkman J, Xiong W (2006) Executive compensation and short-termist behavior in speculative markets. Rev Econ Studies 73(3):577–610

Catalán M (2004) Pension funds and corporate governance in developing countries: what do we know and what do we need to know? J Pension Econ Finance 3(2):197–232

Catalán M, Impavido G, Musalem AR (2000) Contractual savings or stock market development: which leads? J Appl Soc Sci Stud 120(3):445–487

Chevalier J, Ellison G (1999) Career concerns of mutual fund managers. Q J Econ 114(2):389–432

Choi N, Sias RW (2009) Institutional industry herding. J Financ Econ 94(3):469–491

Chordia T, Roll R, Subrahmanyam A (2001) Market liquidity and trading activity. J Finance 56(2):501–530

Corbo V, Schmidt-Hebbel K (2003) Macroeconomic effects of the pension reform in Chile. In: Pension reforms: results and challenges. International Federation of Pension Fund Administrators, Santiago, pp 241–329

Dahlquist M, Punkiwutz L, Stulz R, Williamson R (2003) Corporate governance and the home bias. J Financ Quant Anal 38(1):87–110

Davis EP (1995) Pension funds: retirement income security and capital markets—an international perspective. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Davis EP, Steil B (2001) Institutional investors. MIT Press, Cambridge

de la Torre A, Schmukler S (2006) Emerging capital markets and globalization: the Latin American experience. Stanford University Press and World Bank

Eterovic EF, Silva A, Oyarzun C (2011) Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 81(3):607–636

Fama EF, MacBeth JD (1973) Risk, return, and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Pol Econ 81(3):607–636

Ferson W, Khang K (2002) Conditional performance measurement using portfolio weights: evidence for pension funds. J Financ Econ 65(2):249–282

Flannery MJ, Kwan SH, Nimalendran M (2004) Market evidence on the opaqueness of banking firms’ assets. J Financ Econ 71(3):419–460

Froot KA, Scharfstein DS, Stein JC (1992) Herd on the street: informational inefficiencies in a market with short-term speculation. J Finance 47(4):1461–1484

Gompers PA, Metrick A (2001) Institutional investors and equity prices. Q J Econ 116(1):229–259

Graham JR (1999) Herding among investment newsletters: theory and evidence. J Finance 54(1):237–268

Greenwood R, Nagel S (2009) Inexperienced investors and bubbles. J Financ Econ 93(2):239–258

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M (2000) The investment behavior and performance of various investor types: a study of Finland’s unique data set. J Financ Econ 55(1):43–67

Grinblatt M, Titman S, Wermers R (1995) Momentum investment strategies, portfolio performance, and herding: a study of mutual fund behavior. Amer Econ Rev 85(5):1088–1105

Impavido G, Musalem AR (2000) Contractual savings, stock, and asset markets. World Bank Policy Research Paper 2490

Impavido G, Musalem AR, Tressel T (2003) The impact of contractual savings institutions on securities markets. World Bank Policy Research Paper 2948

Kacperczyk M, Sialm C, Zheng L (2005) On the industry concentration of actively managed equity mutual funds. J Finance 60(4):2379–2416

Kacperczyk M, Sialm C, Zheng L (2008) Unobserved actions of mutual funds. Rev Financ Studies 21(6):2379–2416

Kaminsky G, Lyons R, Schmukler S (2004) Managers, investors, and crises: mutual fund strategies in emerging markets. J Inter Econ 64(1):113–134

Kapur S, Timmermann A (2005) Relative performance evaluation contracts and asset market equilibrium. Econ J 115(506):1077–1102

Lakonishok J, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1992) The impact of institutional trading on stock prices. J Financ Econ 32(1):23–43

Langford B, Faff R, Marisetty V (2006) On the choice of superannuation funds in Australia. J Financ Serv Res 29(3):255–279

Lazen V (2005) El mercado secundario de deuda en Chile. Documento de Trabajo N°5, Superintendencia de Valores y Seguros, Santiago, Chile

Lefort F, Walker E (2002a) Premios por plazo, tasas reales y catástrofes: evidencia de Chile. El Trimestre Económico 69(2):191–225

Lefort F, Walker E (2002b) Pension reform and capital markets: are there any (hard) links? World Bank Social Protection Discussion Paper 0201

Livingston M, Naranjo A, Zhou L (2007) Asset opaqueness and split bond ratings. Financ Manag 36(3):49–62

Morgan DP (2002) Rating banks: risk and uncertainty in an opaque industry. Amer Econ Rev 92(4):874–888

Nofsinger J, Sias RW (1999) Herding and feedback trading by institutional and individual investors. J Finance 54(6):2263–2295

Olivares JA (2005) Investment behavior of the Chilean pension funds. Financial Management Association European Conference Paper 360419

Opazo L, Raddatz C, Schmukler S (2009) The long and the short of emerging market debt. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5056

Piñera J (1991) El cascabel al gato: la batalla por la reforma previsional. Zig-Zag, Santiago

Raddatz C, Schmukler S (2011) Deconstructing herding: evidence from pension fund Investment behavior. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5700

Scharfstein DS, Stein JC (1990) Herd behavior and investment. Amer Econ Rev 80(3):465–479

Shiller RJ, Pound J (1989) Survey evidence on diffusion of interest and information among investors. J Econ Behav Organ 12(1):47–66

Shleifer A, Vishny R (1990) Equilibrium short horizons of investors and firms. Amer Econ Rev 80(2):148–153

Sias RW (2004) Institutional herding. Rev Financ Studies 17(1):165–206

Sias RW (2007) Reconcilable differences: momentum trading by institutions. Financ Rev 42(1):1–22

Sias RW, Starks R (1997) Return autocorrelation and institutional investors. J Financ Econ 46(1):103–131

Stein J (2003) Agency, information, and corporate investment. In: Constantinides G, Harris M, Stulz R (eds) Handbook of the economics of finance. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 115–165

Stein J (2005) Why are most funds open-end? Competition and the limits of arbitrage. Q J Econ 120(1):247–272

The Economist (2008) Money for old hope. Special report on asset management, March 1

Vittas D (1999) Pension reform and financial markets. Harvard Institute for International Development, Development Discussion Paper 697

Voronkova S, Bohl M (2005) Institutional traders’ behavior in an emerging stock market: empirical evidence on polish pension fund investors. J Bus Finance Account 32(7–8):1537–1560

Wermers R (1999) Mutual fund herding and the impact on stock prices. J Finance 54(2):581–622

Yermo J (2005) The contribution of pension funds to capital market development in Chile. Mimeo, Oxford University and OECD

Zurita F (1999) Are pension funds myopic? Revista de Administración y Economía, Catholic University of Chile 39:13–15

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are indebted to the Chilean Superintendency of Pensions for giving us unique data and support that made this paper possible. For very useful comments, we thank Solange Berstein, Matías Braun, Anderson Caputo, Pablo Castañeda, Pedro Elosegui, Eduardo Fajnzylber, Gregorio Impavido, David Musto (the Editor), Gonzalo Reyes, Luis Servén, an anonymous referee, and participants at presentations held at the LACEA Annual Meetings (Buenos Aires, Argentina), NIPFP-DEA Workshop (Delhi, India), Superintendencia de Pensiones and Universidad Alfonso Ibañez (Santiago, Chile), and World Bank Group (Washington, DC). For excellent research assistance, we are especially grateful to Ana Gazmuri and Mercedes Politi. We also thank Alfonso Astudillo, Leandro Brufman, Francisco Ceballos, Lucas Núñez, and Matías Vieyra, who ably helped us as research assistants at different stages of the project, and Jonathan Moore, who edited the paper. The World Bank Research Department and the Knowledge for Change Program provided generous financial support. The views expressed here do not necessarily represent those of the Central Bank of Chile or the World Bank. The authors are with the Central Bank of Chile and the World Bank, Development Research Group, respectively. Email addresses: craddatz@bcentral.cl and sschmukler@worldbank.org.

Appendix 1. The case of Chile: more details

Appendix 1. The case of Chile: more details

Chile and its pension funds are an interesting case to study. Chile not only is a pioneer and introduced a novel pension fund system, but also continuously improves the regulatory environment such that pension funds become better investment vehicles for pensioners. In addition, Chile fosters the development of mutual funds and insurance companies as alternative and complementary investment vehicles. Aside from reforming the institutional investor base, Chile has more broadly implemented and succeeded in a series of macroeconomic and institutional policies to achieve a stable market-friendly economy, where capital markets play an important role and investors have incentives to participate. Furthermore, among many countries, Chile has been regarded as the example to follow in terms of pension fund and capital market reforms.

When Chile introduced the new pension fund system in 1980, contributors were given the choice of remaining in a national state-run DB system or transferring to the new individual account system. All new entrants to the wage workforce would be automatically enrolled in the new scheme and would select a pension fund administrator (PFA) to manage their accounts. The pension funds have been regulated by the Superintendency of Pensions (Superintendencia de Pensiones, SP).

Although pensioners choose their PFA and the specific funds in which they invest, they cannot select individual investments (assets) themselves. The choice of funds was not always available in the new system; it became more flexible over time as investment regulations were relaxed and options increased. During the first 10 years of the system, each PFA managed a unique fund offering no choice to individuals in terms of risk-return combinations. The set of choices was expanded in March 2000 by the introduction of a new fund type (Fund 2), and in August 2002 by the implementation of the multi-fund scheme in which all PFAs started offering a set of five different funds to their contributors (Funds A to E). Each fund type is subject to different restrictions on its asset allocation. Therefore, the entire set of funds offers more flexibility through different risk-return combinations. Depending on their age and gender profile, contributors can choose among a subset of these five funds. In particular, as pensioners come close to retirement they are forbidden to invest in the more risky funds.

Pension funds manage the pensioners’ assets by mostly purchasing securities in capital markets. The managers that the PFAs hire decide the portfolio of each fund and actively reallocate it as they deem necessary. Managers are typically compared with similar funds in other PFAs through returns. Pension funds do not operate like individual life-cycle funds. Moreover, their mandate differs from that of life insurance companies that need to meet the (typically long-term) obligations stipulated in the insurance contracts. They just need to manage the portfolio according to the mandate. Within a PFA, pension fund portfolios are managed separately, but the PFA provides market analysis and asset recommendations for all its funds, resulting in some correlation on portfolio compositions. Most PFAs have managers that specialize in broad asset classes (fixed income and variable income) and participate in the construction of the portfolios of each of the funds.

In terms of the restrictions at the asset level, Chilean PFAs invest in different assets subject to a set of quantitative limits that the law defines and that specify how much pension fund administrators can invest in specific instruments. Pension funds can only invest in assets listed in the pension law and traded in public offerings. These investment limits have been relaxed over time, incorporating quantitative and conceptual changes. However, these limits do not seem to have been binding (except for the case of foreign investments that reached the limit over time). During the multi-fund period of 2002–2005, PFAs invested in only a subset of the assets approved for investment by the Risk-Rating Commission (Comisión Clasificadora de Riesgo, CCR). For example, during this period they invested in 65–72 % of all the approved equity and in 15–18 % of all the approved foreign mutual funds.

Aside from the investment restrictions, pension funds are subject to a minimum return regulation that establishes that administrators are responsible for ensuring an average real rate of return over the last 36 months that exceeds either (i) the average real return of all funds of the same type (i.e., Funds C are benchmarked with other Funds C) minus two percentage points for Funds C, D, and E, and minus four percentage points for Funds A and B, or (ii) 50 % of the average real return of all the funds of the same type, whichever is lower. The average real rate of return to calculate the minimum return changed from 12 months to 36 months in October 1999, giving PFAs more flexibility to deviate in the short term from the industry comparators. PFAs must keep a return fluctuation reserve equal to 1 % of the value of each fund, which is used if the minimum return is not achieved. When the difference is not completely covered by this reserve or the administrator’s funds, the state must provide for it. However, in this case or when the reserve is not restored after being used (in a 15-day period), the PFA’s operating license can be revoked.

After the introduction of the multi-fund scheme in August 2002, investment limits per instrument set by the central bank did not change for domestic instruments during the period 2002–2005. Limits on domestic fixed-income (variable-income) instruments gradually increase (decrease) as funds become less risky. For example, Fund A is the riskiest fund, having the lowest (highest) limits on domestic fixed-income (variable-income) instruments across the five funds. Fund E is the most conservative fund, having the highest limits on fixed-income instruments, the only instruments in which its assets are allowed to be invested. For foreign investments, the limit is set at the PFA level and was relaxed twice during 2003. The maximum allowed by law is 30 % of the value of all funds managed by a single PFA.

Pension funds in Chile are large. Assets under pension fund management increased substantially both in absolute and relative terms. In 2005, pension funds managed around 75 billion dollars, an amount that was almost 2.5 times the 1996 value in real terms. Since their inception in 1981 and 2005, pension funds grew at an average annual rate of 28 % in GDP terms. Furthermore, pension funds held around 10 % of equity market capitalization (which corresponds to around 28 % of free-float), 60 % of outstanding domestic public sector bonds, and 30 % of corporate bonds’ capitalization in 2004.

As assets under management expanded, the industry consolidated. The number of PFAs operating in Chile decreased by two-thirds while the number of pension funds doubled. The number of PFAs decreased from 15 to 6 due to a series of mergers and acquisitions that took place mostly in the late 1990s. Because the number of pension funds in the market has been proportional to the number of PFAs, the number of pension funds increased from 15 (one per PFA) to 30 (five per PFA) from July 1996 to December 2005.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raddatz, C., Schmukler, S.L. Deconstructing Herding: Evidence from Pension Fund Investment Behavior. J Financ Serv Res 43, 99–126 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0155-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0155-x