Abstract

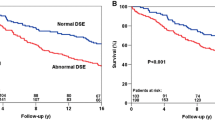

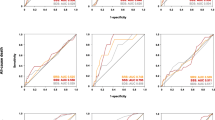

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prognostic value of hemodynamic variables during ergometric stress testing for 99mTc-sestamibi myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (MPS) as compared to several patient-related variables and MPS results with regard to referral to early coronary angiography (<3 months after MPS; CA) as well as cardiac event (CE) free survival in a study population aged ≥70 years. About 90 patients aged ≥70 years (74.5 ± 3.6 years) who underwent ergometric stress/rest MPS were included in this study. About 19 hemodynamic variables during stress testing were assessed. Semiquantitative visual interpretation of MPS images were performed and Summed-Stress-(SSS), Summed-Difference-, and Summed-Rest-Scores were calculated. Emerging CE comprised myocardial revascularization and -infarction as well as cardiac-related death. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed for evaluation of independent prognostic impact of hemodynamic-, MPS- and clinical-variables with regard to referral to early catheterization as well as emerging CE. Kaplan–Meier survival- and log rank analyses were calculated for assessment of CE free survival. History of CAD (Odds ratio; OR: 99.3), low rest heart rate (OR: 14.9) and low peak systolic blood pressure (OR: 15.4) during ergometric stress testing as well as pathological SSS (OR: 48.4) were significantly associated with referral to CA. History of ischemic ECG (OR: 4.7) and pathological SSS (OR: 3.7) independently predicted emerging CE and were associated with a lower CE free survival. In patients aged ≥70 years, CA is independently predicted by clinical variables, pathological results of MPS and hemodynamic variables. In contrast, hemodynamic response to stress testing failed to show any predictive impact on emerging CE.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schulman SP, Fleg JL (1996) Stress testing for coronary artery disease in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 12:101–119

Foot DK, Lewis RP, Pearson TA, Beller GA (2000) Demographics and cardiology, 1950–2050. J Am Coll Cardiol 35:66B–88B

Wang FP, Amanullah AM, Kiat H, Friedman JD, Berman DS (1995) Diagnostic efficacy of stress technetium 99m-labeled sestamibi myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography in detection of coronary artery disease among patients over age 80. J Nucl Cardiol 2:380–388. doi:10.1016/S1071-3581(05)80025-X

Alexander KP, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH et al (2000) Outcomes of cardiac surgery in patients age ≥80 years: results from the National Cardiovascular Network. J Am Coll Cardiol 35:731–738. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00606-3

Batchelor WB, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH et al (2000) Contemporary outcome trends in the elderly undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions: results in 7,472 octogenarians. National Cardiovascular Network Collaboration. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:723–730. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00777-4

Elhendy A, van Domburg RT, Bax JJ et al (2000) Safety, hemodynamic profile, and feasibility of dobutamine stress technetium myocardial perfusion single-photon emission CT imaging for evaluation of coronary artery disease in the elderly. Chest 117:649–656. doi:10.1378/chest.117.3.649

Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H et al (2002) Value of stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography in patients with normal resting electrograms. Circulation 105:823–829. doi:10.1161/hc0702.103973

Berman DS, Hachamovitch R, Kiat H et al (1995) Incremental value of prognostic testing in patients with known or suspected ischemic heart disease: a basis for optimal utilization of exercise technetium-99m sestamibi myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 26:639–647. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(95)00218-S

Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H et al (1996) Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease: incremental prognostic value and use in risk stratification. Circulation 93:905–914

Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Shaw LJ et al (1998) Incremental prognostic value of myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography for the prediction of cardiac death: differential stratification for risk of cardiac death and myocardial infarction. Circulation 97:535–543

Iskandrian AS, Chae SC, Heo J et al (1993) Independent and incremental prognostic value of exercise single-photon emission computed tomographic (SPECT) thallium imaging in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 22:665–670

Shaw LJ, Hachamovitch R, Heller GV et al (2000) Noninvasive strategies for the estimation of cardiac risk in stable chest pain patients: the Economics of Noninvasive Diagnosis (END) study group. Am J Cardiol 86:1–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(00)00819-5

Younis LT, Chaitman BR (1993) The prognostic value of exercise testing. Cardiol Clin 11:229–240

Gibbons RJ, Balady GJ, Beasley JW et al (1997) ACC/AHA guidelines for exercise testing: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Exercise Testing). J Am Coll Cardiol 30:260–311. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00150-2

Elhendy A, Mahoney DW, Khandheria BK, Burger K, Pellikka PA (2003) Prognostic significance of impairment of heart rate response to exercise. Impact of left ventricular function and myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 42:823–830. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00832-5

Lauer MS, Okin PM, Larson MG, Evans JC, Levy D (1996) Impaired heart rate response to graded exercise: prognostic implications of chronotropic incompetence in the Framingham Heart study. Circulation 93:1520–1526

Ellestad MH (1996) Chronotropic incompetence: the implication of heart rate response to exercise (compensatory parasympathetic hyperactivity?). Circulation 93:1485–1487

Lai S, Kaykha A, Yamazaki T et al (2004) Treadmill scores in elderly men. J Am Coll Cardiol 43:606–615. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.051

Gobel FL, Nordstrom LA, Nelson RR, Jorgensen CR, Wang Y (1978) The rate-pressure product as an index of myocardial oxygen consumption during exercise in patients with angina pectoris. Circulation 57:549–556

Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H et al (1995) Gender-related differences in clinical management after exercise nuclear testing. J Am Coll Cardiol 26:1457–1464. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(95)00356-8

Sharir T, Germano G, Kang X et al (2001) Prediction of myocardial infarction versus cardiac death by gated myocardial perfusion SPECT: risk stratification by the amount of stress-induced ischemia and the poststress ejection fraction. J Nucl Med 42:831–837

Oberman A, Jones B, Riley CB (1972) Natural history of coronary artery disease. Bull N Y Acad Med 48:1109–1125

Stratmann HG, Williams GA, Wittry MD, Chaitman BR, Miller DD (1994) Exercise technetium-99m sestamibi tomography for cardiac risk stratification of patients with stable chest pain. Circulation 89:615–622

Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD et al (2003) Is there a referral bias against catheterization of patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction? J Am Coll Cardiol 42:1286–1294. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00991-4

Amanullah AM, Kiat H, Hachamovitch R et al (1996) Impact of myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography on referral to catheterization of the very elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol 28:680–686. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(96)00200-8

Irving JB, Bruce RA, DeRouen TA (1997) Variations in and significance of systolic blood pressure during maximal exercise (treadmill) testing. Am J Cardiol 39:841–848. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(77)80037-4

Lauer MS, Pashkow FJ, Harvey SA, Marwick TH, Thomas JD (1995) Angiographic and prognostic implications of an exaggerated exercise systolic blood pressure response and rest systolic blood pressure in adults undergoing evaluation for suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 26:1630–1636. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(95)00388-6

Morrow K, Morris CK, Froelicher VF et al (1993) Prediction of cardiovascular death in men undergoing noninvasive evaluation for coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med 118:689–695

Weiner DA, McCabe CH, Cutler SS, Ryan TJ (1982) Decrease in systolic blood pressure during exercise testing: reproducibility, response to coronary bypass surgery and prognostic significance. Am J Cardiol 49:1627–1631. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(82)90238-7

Dorn J, Naughton J, Imamura D, Trevisan M, National Exercise Heart Disease Project Staff (2001) Prognostic value of peak exercise systolic blood pressure on long-term survival after myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 87:213–216. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01320-5

Fraser RS (1954) Studies on the effect of exercise on cardiovascular function II. The blood pressure and pulse rate. Circulation 9:193–198

Bruce RA, Gey GO Jr, Cooper MN, Fisher LD, Peterson DR (1974) Seattle Heart Watch. Initial clinical, circulatory and electrocardiographic response to maximal exercise. Am J Cardiol 33:459–469. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(74)90602-X

Dresing TJ, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ et al (2000) Usefulness of impaired chronotropic response to exercise as a predictor of mortality, independent of the severity of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 86:602–609. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(00)01036-5

Brener SJ, Pashkow FJ, Harvey SA et al (1995) Chronotropic response to exercise predicts angiographic severity in patients with suspected or stable coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 76:1228–1232. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(99)80347-6

Lauer MS, Francis GS, Okin PM et al (1999) Impaired chronotropic response to exercise stress testing as a predictor of mortality. JAMA 10:524–529. doi:10.1001/jama.281.6.524

Lauer MS, Mehta R, Pashkow FJ et al (1998) Association of chronotropic incompentence wit hechocardiographic ischemia and prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 32:1280–1286. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00377-5

Huikuri HV, Jokinen V, Syvänne M, Lopid Coronary Angioplasty Trial (LOCAT) Study Group et al (1999) Heart rate variability and progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19:1979–1985

Hinkle LE Jr, Carver ST, Plakum A (1972) Slow heart rates and increased risk of cardiac death in middle-aged men. Arch Intern Med 129:732–748. doi:10.1001/archinte.129.5.732

Vivekananthan DP, Blackstone EH, Pothier CE, Lauer MS (2003) Heart rate recovery after exercise is a predictor of mortality, independent of the angiographic severity of coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 42:831–838. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00833-7

Cole CR, Blackstone EH, Pashkow FJ, Snader CE, Lauer MS (1999) Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality. N Engl J Med 341:1351–1357. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411804

Diaz LA, Brunken RC, Blackstone EH, Snader CE, Lauer MS (2001) Independent contribution of myocardial perfusion defects to exercise capacity and heart rate recovery for prediction of all-cause mortality in patients with known or suspected coronary heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 37:1558–1564. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01205-0

Abidov A, Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW et al (2003) Prognostic impact of hemodynamic response to adenosine in patients older than age 55 years undergoing vasodilator stress myocardial perfusion study. Circulation 107:2894–2899. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000072770.27332.75

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bucerius, J., Joe, A.Y., Herder, E. et al. Hemodynamic variables during stress testing can predict referral to early catheterization but failed to show a prognostic impact on emerging cardiac events in patients aged 70 years and older undergoing exercise 99mTc-sestamibi myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 25, 569–579 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-009-9461-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-009-9461-2