Abstract

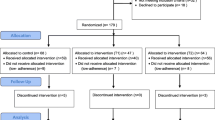

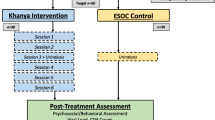

This study describes the results of an online social support intervention, called “Thrive with Me” (TWM), to improve antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence. HIV-positive gay or bisexually-identified men self-reporting imperfect ART adherence in the past month were randomized to receive usual care (n = 57) or the eight-week TWM intervention (n = 67). Self-reported ART outcome measures (0–100 % in the past month) were collected at baseline, post-intervention, and 1-month follow-up. Follow-up assessment completion rate was 90 %. Participants rated (1–7 scale) the intervention high in information and system quality and overall satisfaction (Means ≥ 5.0). The intervention showed modest effects for the overall sample. However, among current drug-using participants, the TWM (vs. Control) group reported significantly higher overall ART adherence (90.1 vs. 57.5 % at follow-up; difference = 31.1, p = 0.02) and ART taken correctly with food (81.6 vs. 55.7 % at follow-up; difference = 47.9, p = 0.01). The TWM intervention appeared feasible to implement, acceptable to users, and demonstrated greatest benefits for current drug users.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

The Antiretroviral Therapy Cohort Collaboration. Life expectancy of individuals on combination antiretroviral therapy in high-income countries: a collaborative analysis of 14 cohort studies. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):293–9.

Cohen MS, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Prejean J, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, HIV Surveillance Report: Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2010, 2012.

Mills EJ, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e438.

Mugavero MJ, et al. Failure to establish HIV care: characterizing the “no show” phenomenon. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(1):127–30.

Simoni J, et al. Efficacy of interventions in improving highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-1 RNA viral load. A meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S23–35.

Simoni J, et al. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: a review of current literature and ongoing studies. Top HIV Med. 2003;11(6):185–98.

Thompson MA, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an international association of physicians in AIDS care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(11):817–33.

Saberi P, Johnson MO. Technology-based self-care methods of improving antiretroviral adherence: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27533.

Page TF, et al. A cost analysis of an internet-based medication adherence intervention for people living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(1):1–4.

Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC. Recent advances (2011–2012) in technology-delivered interventions for people living with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2012;9(4):326–34.

Fisher JD, et al. Computer-based intervention in HIV clinical care setting improves antiretroviral adherence: the LifeWindows project. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1635–46.

Portnoy DB, et al. Computer-delivered interventions for health promotion and behavioral risk reduction: a meta-analysis of 75 randomized controlled trials, 1988–2007. Prev Med. 2008;47(1):3–16.

Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(1):107–15.

Madden M, Zickuhr K. 65 % of online adults use social networking sites. 2011. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Social-Networking-Sites.aspx, Pew Research Center: Washington DC.

Fox S. Peer-to-peer healthcare: many people-especially those living with chronic or rare diseases-use online connections to supplement professional medical advice. Washington DC: Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project; 2011.

Horvath K, et al. Technology use and reasons to participate in social networking health websites among people living with HIV in the US. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):900–10.

Rosser BS, et al. Reducing HIV risk behavior of men who have sex with men through persuasive computing: results of the Men’s INTernet Study-II. AIDS. 2010;24(13):2099–107.

Potosky D. The internet knowledge (iKnow) measure. Comput Hum Behav. 2007;23(6):2760–77.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1992;1:385–401.

Zhang W, et al. Validating a shortened depression scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40793.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96.

Wong MD, et al. The association between life chaos, health care use, and health status among HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1286–91.

Emlet CA. Measuring stigma in older and younger adults with HIV/AIDS: an analysis of an HIV stigma scale and initial exploration of subscales. Res Soc Work Pract. 2005;15:291–300.

Saunders JB, et al. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804.

DeLone WH, McLean ER. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. J Manag Inf Syst. 2003;19(4):9–30.

DeLone WH, McLean ER. Information systems success: the quest for the dependent variable. Inf Syst Res. 1992;3(1):60–95.

Simoni J, et al. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–45.

Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS. 2002;16(2):269–77.

Begg C, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–9.

Dimitrov DM, Rumrill PD Jr. Pretest-posttest designs and measurement of change. Work. 2003;20(2):159–65.

Gottman JM, Rushe RH. The analysis of change: issues, fallacies, and new ideas. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(6):907–10.

Bangsberg DR, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–3.

Pasternak AO, et al. Modest non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy promotes residual HIV-1 replication in the absence of virological rebound in plasma. J Infect Dis. 2012;206(9):1443–52.

Rivet Amico K, Harman JJ, Johnson BT. Efficacy of antiretroviral therapy adherence interventions: a Research Synthesis of Trials, 1996 to 2004. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):285–97.

Anderson PL, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(151):151ra125.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the participants of this study for their time and effort. We also thank Tony Miles at the Positive Project for allowing us to use segments from their video archive for the purpose of this study. This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (5R34MH083549).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horvath, K.J., Michael Oakes, J., Simon Rosser, B.R. et al. Feasibility, Acceptability and Preliminary Efficacy of an Online Peer-to-Peer Social Support ART Adherence Intervention. AIDS Behav 17, 2031–2044 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0469-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0469-1