Abstract

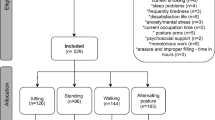

Low back pain (LBP) has been identified as one of the most costly disorders among the worldwide working population. Sitting has been associated with risk of developing LBP. The purpose of this literature review is to assemble and describe evidence of research on the association between sitting and the presence of LBP. The systematic literature review was restricted to those occupations that require sitting for more than half of working time and where workers have physical co-exposure factors such as whole body vibration (WBV) and/or awkward postures. Twenty-five studies were carefully selected and critically reviewed, and a model was developed to describe the relationships between these factors. Sitting alone was not associated with the risk of developing LBP. However, when the co-exposure factors of WBV and awkward postures were added to the analysis, the risk of LBP increased fourfold. The occupational group that showed the strongest association with LBP was Helicopter Pilots (OR=9.0, 90% CI 4.9–16.4). For all studied occupations, the odds ratio (OR) increased when WBV and/or awkward postures were analyzed as co-exposure factors. WBV while sitting was also independently associated with non-specific LBP and sciatica. Vibration dose, as well as vibration magnitude and duration of exposure, were associated with LBP in all occupations. Exposure duration was associated with LBP to a greater extent than vibration magnitude. However, for the presence of sciatica, this difference was not found. Awkward posture was also independently associated with the presence of LBP and/or sciatica. The risk effect of prolonged sitting increased significantly when the factors of WBV and awkward postures were combined. Sitting by itself does not increase the risk of LBP. However, sitting for more than half a workday, in combination with WBV and/or awkward postures, does increase the likelihood of having LBP and/or sciatica, and it is the combination of those risk factors, which leads to the greatest increase in LBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andersson GBJ (1981) Epidemiologic aspects of low-back pain in industry. Spine 6(1):53–60

Andersson GBJ, Örtengren R (1974) Myoelectric back muscle activity during sitting. Scand J Rehabil Med 3:73–90

Black K, Lis A, Nordin M (2001) Association between sitting and occupational low back pain. In: Grammer symposium, Ulm, Germany. Ergomechanics, Chap. 1, pp 11–35

Bongers PM, Hulshof CTJ, Dijkstra L, Boshuizen HC (1990) Back pain and exposure to whole body vibration in helicopter pilots. Ergonomics 33(8):1007–1026

Boshuizen HC, Bongers PM, Hulshof CTJ (1990) Self-reported back pain in tractor drivers exposed to whole body vibration. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 62:109–115

Boshuizen HC, Bongers PM, Hulshof CTJ (1992) Self-reported back pain in fork-lift truck and freight-container tractor drivers exposed to whole body vibration. Spine 17(1):59–65

Bovenzi M, Betta A (1994) Low-back disorders in agricultural tractor drivers exposed to whole body vibration and postural stress. Appl Ergon 25(4):231–241

Bovenzi M, Hulshof CTJ (1999) An update review of epidemiologic studies on the relationship between exposure to whole body vibration and low back pain (1986–1997). Int Arch Occup Environ Health 72:351–365

Bovenzi M, Zadini A (1992) Self-reported low back symptoms in urban bus drivers exposed to whole body vibration. Spine 17(9):1048–1059

Bridger RS, Groom MR, Jones H, Pethybridge RJ, Pullinger N (2002) Task and postural factors are related to back pain in helicopter pilots. Aviat Space Environ Med 73:805–811

Brown JJ, Wells GA, Trottier AJ et al (1998) Back pain in a large Canadian police force. Spine 23(7):821–827

Burdorf A, Zondervan H (1990) An epidemiological study of low-back in crane operators. Ergonomics 33(8):981–987

Burdorf A (1992) Exposure assessment of risk factors for disorders of the back on occupational epidemiology. Scandinavian Work Environ Health 18:1–9

Burdorf A, Naaktgeboren B, deGroot HCWM (1993) Occupational risk factors for low back pain among sedentary workers. J Occup Med 35(12):1213–1220

Chen JC, Chang WR, Shih TS, Chen CJ, Chang WP, Dennerlein JT, Ryan LM, Christiani DC (2004) Using ‘exposure prediction rules’ for exposure assessment: an example on whole-body vibration in taxi drivers. Epidemiol 15(3):293–299

Dainoff MJ (1999) Ergonomics of seating and chairs. In: Salvendy C (ed) Handbook of human factors and ergonomics, chap. 97. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Frymoyer JW, Cats-Baril WL (1991) An overview of the incidences and costs of low back pain. Orthop Clin North Am 22(2):263–271

Griffin MJ (1978) The evaluation of vehicle vibration and seats. Appl Ergon 9(1):15–21

Guo HR, Tanaka S, Cameron LL et al (1995) Back pain among workers in United States: National estimates and workers at high risk. Am J Ind Med 28:591–602

Hartvigsen JK, Kyvik KOP, Leboeuf YC, Lings S, Bakketeig L (2003) Ambiguous relation between physical workload and low back pain: a twin contol study. Occup Environ Med 60:109–114

Hartvigsen J, Leboeuf YC, Lings S, Corder EH (2000) Is sitting-while-at-work associated with low back pain? A systematic critical literature review. Scand J Public Health 28(3):230–239

Heliövaara M, Mäkelä M, Knekt P et al (1991) Determinants of sciatica and low back pain. Spine 16(6):608–614

International Organization for Standardization (1985) Guide for the evaluation of human exposure to whole body vibration. Part 1: General requirements, 1st edn. ISO, Geneva. 1985:ISO 2631–1

Johanning E (1991) Back disorders and health problems among subway train operators exposed to whole body vibration. Scand J Work Environ Health 17:414–419

Johanning E (2000) Evaluation and management of occupational low back disorders. Am J Ind Med 37:94–111

Johanning E, Bruder R (1998) Low back disorders and dentistry—stress factors and ergonomic intervention. In: Murphy DC (ed) Ergonomics and the dental care worker. Washington DC, pp 355–373

Johanning E, Wilder DG, Landrigan PJ, Pope MH (1991) Whole body vibration exposure in subway cars and review of adverse health effects. J Occup Med 33(5):605–612

Kamwendo K, Linton SJ, Moritz U (1991) Neck and shoulder disorders in medical secretaries. Scand J Rehabil Med 23:127–133

Kelsey JL (1975) An epidemiological study of the relationship between occupations and acute herniated lumbar intervertebral discs. Int J Epidemiol 4(3):197–205

Keyserling WM, Punnet L, Fine LJ (1988) Trunk posture and back pain: identification and control of occupational risk factors. Appl Ind Hyg 3(3):87–92

Kopec JA, Sayre EC, Esdaile JM (2004) Predictors of back pain in a general population cohort. Spine 29(1):70–78

Kroemer KHE, Kroemer HB, Kroemer-Ebert KE (1994) Ergonomics: how to design for ease and efficiency, Chap. 8. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Kumar A, Varghese M, Mohan D et al (1999) Effect of whole body vibration on the low back. Spine 24(23):2506–2515

Leclerc A, Tubach F, Landre MF, Ozguler A (2003) Personal and occupational predictors of sciatica in the GAZEL cohort. Occup Med 53:384–391

Lee P, Helewa A, Goldsmith CH, Smythe HA, Stitt LW (2001) Low back pain: prevalence and risk factors in an industrial setting. J Rheumatol 28(2):346–351

Lehman KR, Psihogios JP, Meulenbroek GJ (2001) Effects of sitting versus standing and scanner type on cashiers. Ergonomics 44(7):719–738

Levangie PK (1999) Association of low back pain with self-reported risk factors among patients seeking physical therapy services. Phys Ther 79(8):757–766

Li G, Haslegrave CM (1999) Seated postures for manual, visual and combined tasks. Ergonomics 42(8):1060–1086

Liira JP, Shannon HS, Chambers LW, Haines TA (1996) Long-term back problems and physical work exposures in the 1990 Ontario Health Survey. Am J Public Health 86(3):382–387

Lings S, Leboeuf-Yde C (2000) Whole body vibration and low back pain: a systematic, critical review of the epidemiological literature 1992–1999. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 73:290–297

Liss G, Jesin E, Kusiak A, White P (1995) Musculoskeletal problems among Ontario dental hygienists. Am J Ind Med 28:521–540

Lu JLP (2003) Risk factors for low back pain among Filipino manufacturing workers and their anthropometric measurements. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 18(3):170–176

Macfarlane G, Thomas E, Papageorgiou AC et al (1997) Employment and physical work activities as predictors of future low back pain. Spine 22(10):1143–1149

Magnusson ML, Pope MH, Wilder DG, Areskoug B (1996) Are occupational drivers at an increased risk for developing musculoskeletal disorders? Spine 21(6):710–717

Magora A (1972) Investigation of the relation between low back pain and occupation. 3. Physical requirements: sitting, standing and weightlifting. Scand J Rehabil Med 41:5–9

Maniadakis N, Gray A (2000) The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain 84:95–103

Marras WS, Lavender SA, Leurgans SE et al (1995) Biomechanical risk factors for occupationally related low back disorders. Ergonomics 38(2):377–410

Massaccesi M, Pagnottaa A, Soccettia A, Masalib M, Masieroc C, Grecoa F (2003) Investigation of work-related disorders in truck drivers using RULA method. Appl Ergon 34(4):303–307

Masset D, Malchaire J (1994) Epidemiologic aspects and work-related factors in the steel industry. Spine 19(2):143–146

Masset D, Malchaire J, Lemoine M (1993) Static and dynamic characteristics of the trunk and history of low back pain. Int J Ind Ergon 11:279–290

Merlino LA, Rosecrance JC, Anton D, Cook TM (2003) Symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders among apprentice contruction workers. Appl Occup Environ Hyg 18(1):57–64

Miranda H, Viikari-Juntura E, Martikainen R, Takala EP, Riihimaki H (2002) Individual factors, occupational loading, and physical exercise as predictors of sciatic pain. Spine 27(10):1102–1108

Miyamoto M, Shirai Y, Nakayama Y, Gembun Y, Kaneda K (2000) An epidemiologic study of occupational low back pain in truck drivers. J Nippon Med Sch = Nihon Ika Daigahu Zasshi 67(3):186–190

Moen BE, Bjorvatn K (1996) Musculoskeletal symptoms among dentists in a dental school. Occup Med 46:65–68

Murphy PL, Volinn E (1999) Is occupational low back pain on the rise? Spine 24(7):691–697

Nachemson A, Elfström G (1970) Intravital dynamic pressure measurements in lumbar discs. Scand J Rehabil Med 1(Suppl):1–40

NIOSH (1989) Proposed National strategy for the prevention of musculoskeletal injuries. US Department of Health and Human Services, NIOSH 89–129

NIOSH (1997) Musculoskeletal disorders and workplace factors: a critical review of epidemiologic evidence for work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, upper extremity, and low back. Pub 97–141. Department of Health and Human Services, DHHS

O*NET 5.1 [database online]. US Department of Labor: National O*NET Consortium; 2004. Available at http://www.onetcenter.org/database.html. Accessed April 11, 2004

Özkaya N, Willems B, Goldsheyder D, Nordin M (1994) Whole body vibration exposure experienced by subway train operators. J Low Freq Noise Vib 13(1):13–18

Papageorgiou AC, Croft PR, Ferry S et al (1995) Estimating the prevalence of low back pain in the general population: evidence from the South Manchester Back Pain Survey. Spine 20(17):1889–1894

Pietri F, Leclerc A, Boitel L et al (1992) Low-back pain in commercial travelers. Scand J Work Environ Health 18:52–58

Porter JM, Gyi DE (2002) The prevalence of musculoskeletal troubles among car drivers. Occup Med 52(1):4–12

Pynt J, Higgs J, Mackey M (2002) Milestones in the evolution of lumbar spinal postural health in seating. Spine 27(19):2180–2189

Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders (1995) Critical appraisal form. Spine 20:1S–73S

Reinecke SM, Hazard RG, Coleman K, Pope MH (2002) A continuous passive lumbar motion device to relieve back pain in prolonged sitting. In: Kumar S (ed) Advances in industrial ergonomics and safety IV. Taylor and Francis, London, pp 971–976

Riihimäki H (2002) Low-back pain, its origin and risk indicators. Scand J Work Environ Health 17:81–90

Rohlmann A, Claes LE, Bergmann G, Graichen F, Neef P, Wilke HJ (2001) Comparison of intradiscal pressures and spinal fixator loads for different body positions and exercises. Ergonomics 44(8):781–794

Rotgoltz J, Derazne E, Froom P et al (1992) Prevalence of low back pain in employees of a pharmaceutical company. Isr J Med Sci 28:615–618

Rundcrantz BL, Johnsson B, Moritz U (1991) Pain and discomfort in the musculoskeletal system among dentists. Swed Dent J 15:219–228

Seidel H, Heide R (1986) Long-term effects of whole body vibration: a critical survey of the literature. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 58:1–26

Shinozaki T, Yano E, Murata K (2001) Intervention for prevention of low back pain in Japanese forklift workers. Am J Ind Med 40(2):141–144

Skov T, Borg V, Orhede E (1996) Psychosocial and physical risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders of the neck, shoulders, and lower back in salespeople. Occup Environ Med 53(5):351–356

Toren A (2001) Muscle activity and range of motion during active trunk rotation in a sitting posture. Appl Ergon 32:583–591

Van Deursen LL, Patijn J, Brouwer R et al (1999) Sitting and low back pain: the positive effect of rotatory dynamic stimuli during prolonged sitting. Eur Spine J 8:187–193

Vingard E, Alfredsson L, Hagberg M, Kilbom A, Theorell T, Waldenstrom M, Hjelm EW, Wiktorin C, Hogstedt C (2000) To what extent do current and past physical and psychosocial occupational factors explain care-seeking for low back pain in a working population? Results from the Musculoskeletal Intervention Center-Norrtalje Study. Spine 25(4):493–500

Walsh K, Cruddas M, Coggon D (1992) Low back pain in eight areas of Britain. J Epidemiol Commun Health 46:227–230

Webster BS, Snook S (1990) The cost of compensable low back pain. J Occup Med 32:13–16

Wells R, Moore A, Potvin J, Norman R (1994) Assessment of risk factors for development of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Appl Ergon 25(3):157–164

Wilke HJ, Neef P, Caimi M et al (1999) New in vivo measurements of pressures in the intervertebral disc in daily life. Spine 24(8):755–762

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lis, A.M., Black, K.M., Korn, H. et al. Association between sitting and occupational LBP. Eur Spine J 16, 283–298 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0143-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-006-0143-7