Abstract

Background

The 1910 Flexner Report on Medical Education in the United States and Canada is often taken as the point when medical schools in North America took on their modern form. However, many fundamental advances in surgery, such as anesthesia and asepsis, predated the report by decades. To understand the contribution of educators in this earlier period, we investigated the forgotten career of John Wishart, founding Professor of Surgery at Western University, London Ontario.

Methods

Archives at the University of Western Ontario, University of Toronto, London City Library, and Wellington County Museum were searched for material about Wishart and his times.

Results

A fragmented biography can be assembled from family notes and obituaries with the help of contemporary documents compiled by early 20th century medical school historians. Wishart assisted Abraham Groves in the first reported operation for which aseptic technique was used (1874). He was considered locally to perform pioneering surgery, including an appendectomy in 1886. Wishart was a founding member of the medical faculty at Western University in 1881, initially as Demonstrator of Anatomy and subsequently as its first Professor of Clinical Surgery, which post he held until 1910. Comprehensive notes from his undergraduate lectures demonstrate his teaching style, which mixed organized didacticism with practical advice. The role of the Flexner review in the termination of his professorship is hinted at in minutes of Faculty of Medicine meetings. Wishart was a foundation fellow of the American College of Surgeons and a founding physician of London’s Catholic hospital, St. Joseph’s, despite his own Protestant background.

Conclusions

Wishart’s career comprised all the elements of modern academic surgery, including pioneering service, research, and teaching. Surgery at Western owes as much to Wishart as it does to university reorganization in response to the Flexner report.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

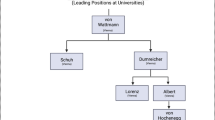

A century ago, educationalist Abraham Flexner undertook a series of on-site reviews of institutions providing medical education in North America. The 1910 Flexner Report on Medical Education in the United States and Canada is often taken as the point when medical schools in North America took on their modern form [1]. The medical school at Western University, currently called the University of Western Ontario, was judged to be below acceptable standards principally because it lacked resources and a “professional” faculty. It responded by hiring new professors and investing in infrastructure. American College of Surgeons founding fellow [2] John Wishart (Fig. 1), who was Western’s first Professor of Surgery, resigned. However, many fundamental advances in surgery, such as anesthesia and asepsis, predated the report by decades. To understand the contribution of educators during this earlier period, we investigated Wishart’s forgotten life and career.

Methods

Archives at the University of Western Ontario, University of Toronto, London City Library, Wellington County Museum, Library of the Surgeon General, and Sisters of St. Joseph of London were searched for material about Wishart and his times. Secondary texts, including local medical histories, were consulted to supplement these primary documents.

Results

Born in Eramosa Township near Guelph, Ontario on May 27, 1850, John Wishart was the seventh and youngest child of farmer W. John Wishart and Jessie Wishart, née McKean (both originally of Edinburgh, Scotland). Wishart received his early education at Guelph Collegiate and Rockwood Academy, a prestigious Ontario private school, following which he became a schoolteacher near his family home.

Wishart soon enrolled at the Trinity Medical School in Toronto. The year in which Wishart began his studies at Trinity is not certain, but it is known that he completed a course in 1867 at the Toronto Lying-In Hospital (Lectures on Midwifery and The Diseases of Women and Children) [3] and that he received a Bachelor of Medicine degree from Trinity in 1871. Wishart went abroad for postgraduate training, becoming a member of the Royal College of Surgeons of England and a fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1877 [4]. Before returning to practice in Canada, he used his medical degree to see the world, spending 2 years as ship’s surgeon on steamers traveling between exotic locales [5–7]. During this period, Wishart also spent time in Fergus, Ontario studying under the surgeon Abraham Groves. The exact years and length of this period are again uncertain, but Wishart assisted Groves in 1874 in performing a laparotomy, which is notable because it was the one of first times that instrument sterilization and modern aseptic technique were used [7–9]. By 1875, Wishart had completed his time with Dr. Groves, received his license from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario [4], and moved to London, Ontario to practice medicine in partnership with a local physician, Friend R. Eccles, in whose house he initially stayed [10, 11]. Wishart soon struck out on his own, opening his practice in London, Ontario in 1880, where he remained for the next 40 years. A Doctor of Medicine degree was granted to Wishart by Trinity College, Toronto in 1881, but records of his thesis have not been preserved [12].

A founder of the medical school in London, Ontario in 1881, Wishart was a professor there for 28 years. During the school’s first academic year (1882–1883), he served as Demonstrator of Anatomy and was in charge of the dissecting room. He was Professor of Clinical Surgery from 1883 until his resignation in 1910 [5]. Wishart also gave lectures to nurses at the City Hospital, later named Victoria Hospital, and at London’s School of Nursing on such topics as “asepsis” and “wounds” [13, 14].

In addition to his role in the medical school, Wishart’s career was notable for several reasons. Perhaps the most tantalizing of these is that he claimed to have performed the first surgery for appendicitis in North America (in 1886). Wishart was also an active participant in local hospital development and administration. He was one of the founders of London’s St. Joseph’s Hospital in 1888 and its first Chief of Staff in 1922 [15]. He sat on the first board of Victoria Hospital and may have served as Chief of Staff there for some years as well [16]. He was also one of the founding members of the American College of Surgeons [2] and was associated with the development of nursing, including equipping the first Victorian Order of Nurses of Upper Canada [17].

On September 19, 1893, Wishart married Minnie Teresa Armstrong (1871–1935) of Whitby, Ontario [18]. The union produced no offspring. Wishart may have had a previous, also childless, marriage. A note in the J.W. Crane collection at the University of Western Ontario, probably written by Crane, refers to Augusta Hawkesworth-Wood as Wishart’s “first wife” [19]. We could find no official record of this marriage or of Augusta’s death. We did find that a female with a similar name lived with Wishart’s former partner Dr. Eccles at the time of the census in 1881 [20]. In addition, a woman of the same name and age later married Dr. William H.B. Aikin, the son of Wishart’s Professor of Surgery in Toronto, in 1887 [21].

Details regarding Wishart’s death are scant. He passed away at St. Joseph’s Hospital in the early morning of November 4, 1926 after a protracted unidentified illness. Wishart had undergone surgery for that illness the previous July, which was reportedly successful but left him with “insufficient strength to regain his former health and vigor, and practically from the first his recovery was doubtful” [6]. At the time of his death, all his siblings had already died, and his sole familial survivor was his wife, Minnie, who passed away in Vancouver 9 years later [6, 22]. Wishart’s effects, which included a large library, were moved to Vancouver after his death and have since been lost [22]. John and Minnie Wishart were buried together in Woodland Cemetery in London [23]. The loss of Dr. Wishart as both a person and a noted surgeon was deeply felt in London, and his memory was honored by lengthy front page obituaries in the London Free Press and the London Advertiser. A brief obituary also appeared in the November 5, 1926 edition of the New York Times [24].

Discussion

Trained at the University of Toronto at the same time as William Osler and Abraham Groves, Wishart received a particularly strong education in anatomy from Professor J.H. Richardson, but his clinical training was impeded by hospital disruptions at that time [25]. Abraham Groves said he never saw the abdomen opened during his training because of the prohibitive risk of septic complications [7]. Surgery at the time was restricted to setting bones, draining abscesses, and resecting peripheral tumors. Although this probably explains why Wishart traveled to London, England for further training, surgery in Toronto was no different from that in most of Europe and North America.

Surgery was about to change, however, because of the availability of reliable anesthesia and strategies to avoid infection. In 1870, Ontario’s Chief Examiner, Dr. John Sullivan, introduced, as a licensing requirement, an oral test of anatomy using a cadaver for the first time in the British Empire [26]. This may have prepared Ontario students in particular for the coming revolution in surgery. On his return from Britain, Wishart was in a select group of physicians in Canada with a Royal College fellowship and a practice limited to surgery.

We do not have much information on the training Wishart received in London (UK). He would certainly have been exposed to Listerism and use of the carbolic spray. On May 5, 1874, Wishart assisted Dr. Abraham Groves (Fergus, Ontario) in an operation that included early use of modern aseptic technique [8, 9] The case, which included laparotomy and oopherectomy, was the first reported instance where the surgeons scrubbed and surgical instruments including sponges were sterilized by boiling to avoid infection [27]. Unlike Lister, who believed that infections were spread through the air, Groves theorized that surgical infections were spread by contact with body fluids in a manner similar to typhoid in drinking water. Wishart’s own practice later was similar to that of modern times: a blend of strict asepsis that he learned from Groves and antisepsis that he saw in London (UK) [28]. As a teacher he lectured on this topic not only to medical students but also to nurses who, he believed, had an important role to play in preventing surgical infections [14].

A notice published in the New York Times the day after Wishart’s death extolled him as an “eminent surgeon, who was credited here with having performed the first modern operation for appendicitis” [24]. A full-length obituary in the London Advertiser similarly credited him with having performed the first appendectomy in North America [7], an attribution that has been echoed by local historians [17]. Notwithstanding these assertions, little direct information is available to substantiate the claim. It is likely that Wishart performed the operation in question in 1886, when he removed an inflamed appendix during surgery for an abdominal abscess [17]. The obituary reference includes a direct quotation from Wishart [7].

It was rather funny the way this operation came about…. The patient had a large abscess and I really operated for that. Then it was that I discovered that he also had what we called inflammation of the bowels. So I took out his appendix. That was the first time it was ever done.

In fact, it was not the first time it was ever done. The first appendectomy for acute appendicitis probably occurred in Britain in 1848, performed by Dr. Henry Hancock [29]. The two other major claimants to the first appendectomy in North America are Dr. Richard J. Hall of New York (in 1886) [29] and Dr. Abraham Groves (in 1883) [8, 9] with whom Wishart worked early in his career. In Canada at the time of Wishart’s surgery, removal of the appendix was not standard practice for “inflammation of the bowels,” which resulted in a devastating and commonly fatal illness. Fitz’s landmark description of appendicitis was published that same year, 1886, and acceptance of appendectomy occurred several years later [29]. It is not possible to give Wishart the credit for the first appendectomy in North America based on the available information, but it is clear that he was an innovative surgeon performing this surgery in advance of many of his contemporaries.

In May 1881, a group of influential physicians in the London (Ontario) area were invited by the chancellor of the newly established Western University (founded in 1878) to a meeting to discuss the creation of a medical school there [30]. Wishart was one of nine physicians in attendance at the initial meeting and at another meeting 2 days later when they established the first medical faculty [5, 30, 31]. These initial lecturers became part owners of the school and were paid based on what was left after expenses were covered [32]. These financial arrangements, which Flexner found abhorrent, may well have been the basis for his negative review more than two decades later. Extant accounts indicate that during his time as professor Wishart inspired in his students a sentiment “akin to hero worship” [33]. He was known for his clear, methodical lectures, which used a primarily didactic method complemented with personal anecdotes, and he has been described as having an outstanding ability to impart knowledge [13]. Only one university lecture, undergraduate urology, survives in the form of notes taken by a student. It shows a systematic approach to clinical history and physical examination that is similar to what is taught today.

Wishart was nowhere nearly as productive as his mentor Abraham Groves with respect to medical publishing. We only found two articles written by him, one concerning nephrectomy for hydronephrosis and the other on surgery for strangulated inguinal hernia repair [34, 35]. Each provides a glimpse of the challenges faced by surgeons during the late 19th century. Diagnosis was difficult in the absence of imaging. Wishart advocated exploratory laparotomy, a relatively new procedure, in cases of uncertainty. His description of transabdominal nephrectomy carefully mentions the appropriate surgical planes. His doubt about whether to excise the cyst or the kidney—or do nothing—is expressed through a concise review of the medical literature of the time, in which previous articles are cited by authors’ names without a bibliography.

Flexner estimated that Canada needed to graduate 250 physicians a year to service its population. He believed that this would be best achieved by concentrating medical education in Toronto and Montreal and closing schools in Halifax, Quebec City, Kingston, and London [1]. Wishart resigned shortly after the 1910 publication of the report that was similarly critical of many schools in the United States. While several medical schools in the United States closed as a result of the report, Canada’s schools, including Western, instituted financial reforms and invested in Flexner’s keystone parameters: library, laboratory, and pharmacy. Evidence from Faculty of Medicine meeting minutes around this time suggests that Wishart’s professorship may have been terminated as part of this process [36].

Several aspects of Wishart’s personal life merit comment. His possible first marriage to Augusta Hawkesworth-Wood may have resulted from a liaison developed during the time they both stayed with Dr. Eccles. This fact, and the poor regard in which divorce was held, did not adversely effect either party’s reputation. Wishart was descended from prominent Scottish reformers, and he was a lifelong practicing Presbyterian [37], but the professional relationship that was mutually most treasured was that with the Roman Catholic Sisters of St. Joseph [38]. Wishart possessed an unremitting dry and sarcastic sense of humor, and he was regarded as exceedingly modest, holding a “withering contempt and scorn” for ostentation and egoism [19, 39]. Wishart’s interests included reading, especially biographies of prominent Canadian and British men [40]. Loss of his personal and medical library is unfortunate.

Wishart’s contribution to the development of academic surgery at the University of Western Ontario is more significant than any of the cosmetic changes that were made in response to the Flexner Report. His eulogy was given by his successor in the Chair of Surgery, Dr Hadley Williams, through whom Wishart’s contribution was passed on [5].

No surgeon ever gave better advice, whether to the physician, the student, or the patient. He was one of the few greatly conservative surgeons of our period, was always very careful in trying out new theories. Few men on the American continent understood better the basic principles of surgery, and none surpassed him in sound, common sense and good judgment. An operator of rare skill, he was as tender as a child, and ever had the patient’s welfare at heart.

References

Flexner A (1910) Medical education in the United States and Canada: a report to the Carnegie foundation for the advancement of teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, New York, pp 322–323. http://www.archive.org/details/medicaleducation00flexiala/. Accessed 20 June 2010

Anonymous (1913) A list of fellows. American College of Surgeons, Chicago, p 8. http://www.archive.org/stream/yearboo1913ameruoft#page/8/mode/2up/search/wishart/. Accessed 18 June 2011

Anonymous (1867) Toronto lying-in hospital, course certificate (March 10, 1867). Wishart collection. University of Western Ontario Archives and Research Collections Centre, London

Anonymous (1882) Ontario medical register. The College of Physicians and Surgeon of Ontario, Toronto, p 109. http://www.archive.org/stream/publishedontario1882coll#page/108/mode/2up/. Accessed 19 June 2011

Barr ML (1977) A century of medicine at western. The University of Western Ontario, London

Obituary (1926) Dr. John Wishart dies after four months’ illness. London Free Press, London, pp 1–7

Obituary (1926) Dr. John Wishart. London Advertiser, London, November 4

Groves A (1934) All in the day’s work; leaves from a doctor’s case-book. Macmillan, Canada

Geddes CR, McAlister VC (2009) A surgical review of the priority claims attributed to Abraham groves (1847–1935). Can J Surg 52:E126–E130

Cook JM (1937) Letter to Dr. Edwin Seaborn. Seaborn collection. Vol: Doctors 1000. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Bayly B. Reminiscence by Ben Bayly. Seaborn collection. Vol: Reminiscences 33. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Anonymous (1881) Johannem Wishart, doctoris in medicina et magistri in chirurgia. Trinity College, Toronto. Wishart collection, University of Western Ontario Archives and Research Collections Centre, London

Anonymous. Chronicles of St. Joseph’s Hospital, London, ON. Vol 1: 1888–1942. Sisters of St. Joseph of London Archives, London

Anonymous (1898) Lectures to nurses at city (Victoria) hospital. Wishart collection. University of Western Ontario Archives and Research Collections Centre, London

Stephen RA, Smith LM (1988) The history of St. Joseph’s hospital: faith and caring. St. Joseph’s Health Centre, London

Anonymous. Seaborn collection. Vol: Hospitals 940. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Seaborn E (1944) The march of medicine in western Ontario. Ryerson Press, Toronto, p 368

Anonymous. Ontario, Canada marriages 1857–1924. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Wishart J. Crane index. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Anonymous (1881) Census of Canada. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Hayter C (2011) William Henry, Beaufort Aikins. Dictionary of Canadian biography. http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?&id_nbr=8001&interval=20&&PHPSESSID=53reurgm8mbdsebqsct9mu01g0/. Accessed 19 June 2011

Winslow RM (1938) Letter from R.M. Winslow of the Canada Trust Company to Dr. Edwin Seaborn re estate of Dr. John Wishart. Seaborn Collection. Vol: Doctors 1603. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Anonymous. Register of cemetery transcriptions. Woodland Cemetery, London

Wishart J (1926) New York Times. November 5

Elliott JH (1942) Osler’s class at the Toronto school of medicine. CMAJ 47:161–165

Gibson W (2011) Senator The Hon. Michael Sullivan, MD. CCHA Report 6 (1938–1939), pp 85–93. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/17636. Accessed 20 June 2011

Groves A (1874) Case of ovariotomy. Canada Lancet 6:345–347. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/17628/. Accessed 20 June 2011

Anonymous. Seaborn collection. Vol: Reminiscences 426. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Kelly HA, Hurdon E (1905) The vermiform appendix and its diseases. Saunders, Philadelphia, pp 43–44

McKibben PS (1928) The Faculty of Medicine of the University of Western Ontario: history. University of Western Ontario, London

Anonymous. Seaborn collection. Vol: Doctors 674. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Godfrey CM (1979) Medicine for Ontario: a history. Mika Publishing, Belleville

Anonymous. Seaborn collection. Vol: Reminiscences 593. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Wishart J (1890) Abdominal nephrectomy for hydro-nephrosis, with a report of two operations. Montreal Med J 19:1–10. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/27929. Accessed 20 June 2010

Wishart J (1895) The treatment of strangulated hernia. Canada Lancet 27:197–202. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/17609/. Accessed 22 June 2011

Anonymous (1910) Faculty of medicine minutes 1881–1913 (September 19, October 13, October 27). University of Western Ontario Archives and Research Collections Centre, London

Anonymous (2004) Tweedsmuir history books, Belwood Women’s Institute, Belwood/West Garafraxa Township, Vol 5, pp 206, 341–345. Wellington County Museum & Archives, Fergus

Hennessey G (Sister). Chronicles of the Sisters of St. Joseph of the Diocese of London, Ontario, 1868–1932. Sisters of St. Joseph’s of London Archives, St. Josephs Hospital, London

Cline C. Seaborn collection. Vol: Doctors 1599. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Dearness N. Notes of Dr. John dearness. Seaborn collection. Vol: Doctors 1600. Ivey Family London Room, Central Library, London

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Claydon, E., McAlister, V.C. The Life of John Wishart (1850–1926): Study of an Academic Surgical Career Prior to the Flexner Report. World J Surg 36, 684–688 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1407-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-011-1407-x