Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We studied the physiological, metabolic and hormonal mechanisms underlying the elevated risk of type 2 diabetes in carriers of TCF7L2 gene.

Methods

We undertook genotyping of 81 healthy young Danish men for rs7903146 of TCF7L2 and carried out various beta cell tests including: 24 h glucose, insulin and glucagon profiles; OGTT; mixed meal test; IVGTT; hyperglycaemic clamp with co-infusion of glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 or glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP); and a euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp combined with glucose tracer infusion to study hepatic and peripheral insulin action.

Results

Carriers of the T allele were characterised by reduced 24 h insulin concentrations (p < 0.05) and reduced insulin secretion relative to glucose during a mixed meal test (beta index: p < 0.003), but not during an IVGTT. This was further supported by reduced late-phase insulinotropic action of GLP-1 (p = 0.03) and GIP (p = 0.07) during a 7 mmol/l hyperglycaemic clamp. Secretion of GLP-1 and GIP during the mixed meal test was normal. Despite elevated hepatic glucose production, carriers of the T allele had significantly reduced 24 h glucagon concentrations (p < 0.02) suggesting altered alpha cell function.

Conclusions/interpretation

Elevated hepatic glucose production and reduced insulinotropic effect of incretin hormones contribute to an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in carriers of the rs7903146 risk T allele of TCF7L2.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several studies have reported a link between variants in the TCF7L2 gene and type 2 diabetes [1–8] and in a recent meta-analysis, rs7903146 of TCF7L2 was associated with type 2 diabetes with allelic odds ratios of 1.46, making it the single strongest known genetic risk factor for type 2 diabetes [9].

TCF7L2 is expressed in the pancreatic beta cell, and there is evidence of reduced insulin secretion in carriers of the rs7903146 risk T allele [2, 10–12]. It has been suggested that the association with type 2 diabetes may be mediated through defects in the enteroinsular axis [3, 12, 13]. TCF7L2 encodes a transcription factor that binds to the promoter of the proglucagon gene, which in turn encodes glucagon, glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 and GLP-2 [14]. Inappropriately increased glucagon secretion is a described abnormality in individuals with type 2 diabetes [15]. However, it is unknown whether this abnormality is present in prediabetic patients or whether it may be secondary to the diabetic state as such. Reduced secretion of GLP-1 and impaired insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) have been reported in type 2 diabetes patients [16–18]. Interestingly, Schafer et al. recently reported normal GLP-1 secretion but reduced effect of GLP-1 upon stimulation of insulin secretion in rs7903146 T allele carriers [12]. However, the extent to which GIP secretion or action is influenced by TCF7L2 variants is unknown. Lyssenko et al. [11] found that basal endogenous glucose production (EGP) was elevated in CT/TT carriers of rs7903146 of TCF7L2 in the face of normal fasting plasma glucagon levels and that rs7903146 had no impact on peripheral insulin action. It is not known whether rs7903146 influences the suppressive effect of insulin on hepatic glucose production. Finally, no data are available addressing the impact of the TCF7L2 genotype on 24 h profiles of plasma glucose, insulin and glucagon.

In this study we performed detailed metabolic characterisation of young healthy glucose-tolerant men with and without the TCF7L2 rs7903146 risk T alleles. We investigated 24 h profiles of plasma insulin, plasma glucagon and plasma glucose and performed euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamps combined with [3H]glucose tracer infusions to study peripheral insulin action and hepatic glucose production. We studied the secretion of GLP-1 and GIP during a meal test and the action of the incretin hormones during a mild hyperglycaemic clamp (7 mmol/l) with infusion of either GLP-1 or GIP. Finally, we analysed fasting proglucagon and glucagon levels to explore whether TCF7L2 genotype influences alpha cell function.

Methods

Participants

DNA was collected from 81 healthy white men aged 18 to 23 years. All participants are participating in a large-scale ongoing study programme aimed at determining the impact of the intrauterine environment and low birthweight on development of type 2 diabetes later in life, and have been extensively metabolically characterised [19, 20]. Consequently, half of the participants had birthweights below the 10th percentile (2,800–3,010 g) and the other half had birthweights in the upper normal range (3,390–4,300 g). All participants were born at term and none had parents, grandparents or siblings with any type of diabetes; none was receiving medication known to interfere with glucose homeostasis. Freathy et al. [21] found each risk allele of the rs7903146 variant to be associated with an increase in birthweight by 18 g, which was subsequently explained by maternal hypoinsulinaemia and hyperglycaemia in pregnancy and consequently increased offspring birthweight. Since birthweight was an original inclusion variable, this was adjusted for in all analyses. The protocol was approved by the regional ethics committee and procedures were performed according to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. After thorough written and oral explanation of the study all participants gave their written consent.

Experimental protocols

Detailed descriptions of the study procedures have previously been provided [19, 20]. All 81 participants underwent standard blood testing after an overnight fast (serum triacylglycerol, serum LDL- and HDL-cholesterol, serum alanine transaminase, serum thyroid-stimulating hormone, haemoglobin), anthropometric measurements, blood pressure and a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan. In addition, 34 of the 81 participants underwent the four following tests after a 10 h fast:

-

1.

24 h profiles of plasma glucose, plasma insulin and plasma glucagon. Blood samples were collected at predefined time points (08:00, 09:45, 10:45, 12:45, 16:30, 18:30, 23:00, 03:00 and 08:00 hours) throughout the 24 h period. Standardised meals were served at 08:15, 11:15, 17:00 and 20:30 hours. A light bicycle exercise was performed at 10:00 and 13:00 hours.

-

2.

OGTT. A standard 2 h 75 g OGTT was performed. Blood samples for glucose were drawn at: 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min. Insulin, C-peptide, GLP-1 and GIP were assessed at 0, 30 and 120 min.

-

3.

IVGTT. A 30 min IVGTT was performed. At −1 min a bolus of 0.3 g/kg glucose was given. Blood samples for glucose, insulin and C-peptide were drawn at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, 20 and 30 min.

-

4.

Euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamps. A primed-continuous infusion of [3-3H]glucose (bolus 40.3 KBq, 0.403 KBq/min) was initiated at 0 h. A primed-continuous insulin infusion (square wave bolus 2 IU, 10 mU m−2 min−1) was begun at 150 min, continued for 120 min and increased to 40 mU m−2 min−1 for another 120 min. Steady state was defined as the last 30 min of each 2 h basal, low-insulin and high-insulin clamp period. Variable infusion of glucose (180 g/l) enriched with [3H]glucose (50.9 KBq/500 ml [10 mU m−2 min−1], 203.5 KBq/500 ml [40 mU m−2 min−1]) was used to maintain euglycaemia during insulin infusion.

Forty-seven of the 81 participants underwent the following three tests after a 10 h fast: (1) a 2 h standardised mixed meal tolerance test (2,370 kJ), with plasma being drawn for glucose, insulin, C-peptide, GLP-1 and GIP determination at 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105 and 120 min; (2) hyperglycaemic clamps (7 mmol/l; 2 h) in conjunction with primed continuous infusion of either GLP-1 or GIP, performed on separate days. Glucose infusion was initiated at −30 min and terminated at 120 min. At −2 min, a bolus of either GLP-1 or GIP was infused to increase the plasma concentration to approximately 120 and 1,000 pmol/l, respectively. At 0 min, a continuous infusion of GLP-1 (60 pmol kg−1 h−1) or GIP (240 pmol kg−1 h−1) was initiated and terminated at 120. For these experiments synthetic GLP-1 and GIP were purchased, dissolved and dispensed as previously described [20]. The peptides were more than 97% pure and identical to the natural human peptides by HPLC, mass and sequence analysis.

Analytical procedures

Plasma glucose, plasma insulin and plasma C-peptide were determined as previously described [19, 20]. Serum total proinsulin concentrations were measured using two-site enzyme-linked immuno adsorbent assay (sandwich ELISA) with monoclonal antibodies [22]. The assay shows 0% cross-reactivity with insulin and C-peptide. Between-batch CVs were 0.0474 at 2.3 pmol/l, 0.067 at 5.1 pmol/l and 0.087 at 10 pmol/l. Blood for analysis of plasma GLP-1 and plasma GIP was sampled in heparin-EDTA tubes with addition of aprotinin, immediately cooled on ice and centrifuged at 4°C for 20 min. Plasma was stored at −20°C until analysis. Plasma samples were assayed for GLP-1 immunoreactivity using a radioimmunoassay specific for amidated C-terminus of the GLP-1 molecule. Intact, biologically active GIP was measured using a newly developed assay specific for the intact N-terminus of GIP. This assay cross-reacts less than 0.1% with GIP(3-42) or with the structurally related peptides GLP-1(7-36) amide, GLP-1(9-36) amide, GLP-2(1-33) and GLP-2(3-33) or glucagon at concentrations of up to 100,000 pmol/l. Glucagon concentrations were measured after extraction of plasma with 70% ethanol (vol./vol., final concentration). The antibody employed (code no. 4305) was directed against the C-terminus of the glucagon molecule and therefore mainly measured glucagon of pancreatic origin [23]. A detailed description of the analysis of glucagon, GLP-1 and GIP is provided in Electronic supplementary material (ESM).

Statistical methods

The effect of TCF7L2 rs7903146 genotype on various outcomes was evaluated by linear regression analysis and data were adjusted for birthweight and sampling period. Neither correction for birthweight nor sampling period had a significant impact on the results. All variables were checked for normal distribution and if necessary logarithmically transformed prior to analysis. Tables show means ± SEM values unless otherwise indicated. A p < 0.05 (two-tailed analysis) was considered to be statistically significant. Due to a relatively low number of individuals, homozygous and heterozygous carriers of the T allele were pooled in the analysis and a dominant model was applied.

Calculations

The AUC was calculated by the trapezoidal method during 24 h study, OGTT and IVGTT. Basal and insulin-stimulated glucose turnover rates, including disposal rates (R d), glycolytic flux, glucose oxidation, glucose storage and EGP were measured during euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp. Detailed information on these calculations is provided in the ESM. During euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp the insulin sensitivity index (Si R d) was defined as (R d 40 mU − R d basal)/(plasma insulin40 mU − plasma insulinbasal) × (plasma glucose40 mU) (mg [kg FFM]−1 min−1 [pmol/l insulin]−1 [mmol/l glucose]−1), where FFM denotes fat-free mass. In the IVGTT, insulin secretion rates (ISR) were calculated using the 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 min concentrations after initiation of the glucose bolus. We used clamp-based estimate of insulin sensitivity (Si Rd) to calculate disposition indices during the IVGTT, namely: D i IVGTT (AUCISR 0–10/AUCglu 0–10) × Si R d (mg [kg FFM]−1 min −1 [mmol/l glucose]−2); and during the OGTT: D i OGTT ([AUCins/AUCglu] × Si R d) (mg [kg FFM]−1 min−1 [mmol/l glucose]−2). During the meal test, AUCs were calculated for plasma glucose, GLP-1 and GIP. ISRs were estimated by deconvolution of the measured C-peptide concentrations by applying population-based individual variables for C-peptide kinetics and expressed as picomoles per kilogram body weight, as described previously [24, 25]. Changes in ISR in response to changes in plasma glucose during the meal test express the efficacy by which changes in plasma glucose concentrations, amino acids and gut factors (i.e. GLP-1 and GIP) stimulate insulin secretion. Therefore, the relationship between plasma glucose concentrations and ISRs during the meal test was evaluated by cross-correlation analyses in each patient. The relationship was linear in all participants and the slope of the line was used as an index (β-index) of beta cell response to glucose (and incretin hormones). The β-index was not corrected for differences in BMI, since body weight was accounted for when calculating ISR. The combined smoothing and deconvolution method may induce a tendency to flatten rapid peaks in secretion resulting in early rise and delayed decrease. For hyperglycaemic clamps with co-infusion of GLP-1 or GIP, the first-phase insulin response was defined as ISR AUC 0–20 min and the second-phase response as ISR AUC 20–120 min.

Genotyping

TCF7L2 rs7903146 was genotyped using allelic discrimination performed with an ABI 7900 system (KBioscience, Hoddesdon, UK). The genotype distribution obeyed Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (p > 0.05). The minor allele frequency of rs7903146 was 27.2% (95% CI 20.3–34.2] with a genotype frequency for CC, CT and TT of 54%, 37% and 9% respectively. The overall genotyping success rate was >96%.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

As shown in Table 1, the T allele of rs7903146 was significantly associated with elevated HbA1c, reduced fasting insulin and higher proinsulin/insulin ratio, whereas fasting plasma glucose levels were not significantly different. Fasting plasma glucagon was reduced in the sample of 34 participants but not significantly reduced in the combined group (n = 81) of T allele carriers.

24 h profiles

Figure 1 shows that while no effect of genotype was observed on plasma glucose concentrations, plasma insulin (AUCins 24 h: CT/TT: 1,752 ± 202 vs CC: 2,314 ± 182 pmol l−1 day−1; p < 0.05) and plasma glucagon (AUCglucagon 24 h: CT/TT: 523 ± 49 vs CC: 694 ± 45 ng l− day−1; p < 0.02) concentrations were significantly reduced in T allele carriers.

Twenty-four hour profiles, where 0 and 24 h correspond to 08:00 hours. a Plasma (P) glucose (p < 0.64 for AUC); b insulin (p < 0.05 for AUC) and c glucagon (p < 0.02 for AUC). Data presented as mean ± SEM, p values are corrected for birthweight. *p < 0.05 between genotypes at indicated times. Broken lines with white triangles, risk T allele carriers (n = 15); continuous lines with black circles, wild-type participants (n = 19)

Euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp

Glucose turnover rates were evaluated in the basal state, and at 10 and 40 mU m−2 min−1 of insulin administration. As seen in ESM Table 2, glucose disposal rates increased with increasing plasma insulin levels, independently of genotype. Plasma glucose and plasma insulin levels were similar between genotypes during the three steady-state periods (ESM Fig. 1). By contrast, EGP was elevated at all three physiological insulin levels in risk T allele carriers, reaching significance at the basal state (EGPbasal CT/TT: 3.08 ± 0.14 vs CC: 2.76 ± 0.09 mg [kg FFM]−1 min−1; p < 0.05) and during the high insulin clamp where glucose production in T allele carriers was twice that of wild-type participants (EGP40 mU; CT/TT: 1.84 ± 0.31 vs CC: 0.87 ± 0.28 mg [kg FFM]−1 min−1; p < 0.03). Plasma glucagon was lower in T allele carriers during the basal period (ESM Fig. 1). Basal and insulin-stimulated glucose storage as well as the insulin sensitivity index and glucose oxidation, non-oxidative glucose metabolism and fat oxidation were similar in the two genotype groups during all experimental settings (ESM Table 2). The difference in BMI between genotype groups in this cohort was 0.2 kg/m2. Correcting for this variable had no influence on the results.

OGTT

Plasma glucose concentrations during the OGTT were identical in the two genotype groups (Fig. 2). A trend towards lower plasma insulin levels was observed in risk allele carriers at all time points (AUCins 0–120 CT/TT: 24,968 ± 7,373 vs CC: 39,386 ± 6,623 pmol l−1 [120 min]−1; p = 0.16) while disposition index did not differ (D i OGTT CT/TT: 5.7 × 10−10 ± 9.1 × 10−11 vs CC: 5.5 × 10−10 ± 8.3 × 10−11 p = 0.73). GLP-1 and GIP concentrations did not differ between genotypes (AUC GLP-10–120 CT/TT: 2,577 ± 326 vs CC: 3,086 ± 293, pmol l−1 [120 min]−1; p = 0.26; AUC GIP0–120 CT/TT: 3,842 ± 346 vs CC: 3,896 ± 323 pmol l−1 [120 min]−1; p = 0.91).

OGTT. a Plasma glucose (p = 0.57 for AUC); b plasma insulin (p = 0.15 for AUC); c GLP-1 (p = 0.26 for AUC); and d GIP (p = 0.91 for AUC). Data presented as mean ± SEM, p values are corrected for birthweight. No significant difference was seen at any time point. Broken lines with white triangles, risk T allele carriers (n = 15); continuous lines with black circles, wild-type participants (n = 19)

IVGTT

There were no significant differences in plasma glucose or in first or late phase of insulin secretion between genotypes (Fig. 3). Di did not differ between genotypes (CT/TT: 0.84 ± 0.09 vs CC: 0.66 ± 0.07; p = 0.11). The overall insulin response in carriers of the T allele was reduced during the OGTT compared with the IVGTT (AUCinsOGTT/AUCinsIVGTT CT/TT: 1.45 ± 0.16 vs CC: 2.00 ± 0.22; p = 0.06), supporting an imbalanced enteroinsular axis. To quantify the incretin abnormality, we compared the ratio of AUCinsulin OGTT 0–30 − AUCinsulin IVGTT 0–30/AUCinsulin OGTT 0–30 [11] between genotypes. This surrogate marker of incretin effect was insignificantly decreased in carriers of the risk T allele (CC: 2.00 ± 0.22 vs CT/TT: 1.45 ± 0.16; p = 0.15).

IVGTT. a Plasma (P) glucose (p = NS for AUC); b ISRs (p = NS for AUC); c P-insulin (p = NS for AUC); and d plasma C-peptide (p = NS for AUC). Data presented as mean ± SEM, p values are corrected for birthweight. Broken lines with white triangles, risk allele carriers (n = 15); continuous lines with black circles, wild-type participants (n = 19)

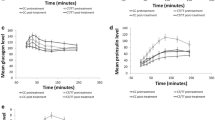

Meal test

ISRs (Fig. 4) mirrored the changes in plasma glucose concentrations and returned to near fasting levels after 90 min in both genotype groups. Both incretin hormones exhibited prolonged profiles that did not reach fasting levels at 120 min. Neither glucose levels nor ISR differed significantly between genotype groups. Notably, when expressed as beta cell responsiveness to changes in glucose (β-index), i.e. the slope of the relationship between the calculated ISR and the corresponding blood glucose concentrations, carriers of the at-risk T allele had significantly reduced postprandial beta cell responsiveness (CT/TT: 2.85 ± 0.29 vs CC: 4.15 ± 0.27 pmol insulin kg−1 min−1 [mmol glucose]−1 l−1; p < 0.003) even after accounting for insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR); (p < 0.006). There was a trend towards reduced postprandial secretion of GIP in risk allele carriers (CT/TT: 5583 ± 470 vs CC: 6691 ± 462 pmol l−1 [120 min]−1; p = 0.086) only reaching significance at 45 min (CT/TT: 46 ± 4 vs CC: 61 ± 5 pmol l−1; p = 0.035). GLP-1 concentrations did not differ significantly between genotypes.

Meal test. a Plasma (P) glucose (p = 0.45 for AUC); b ISRs (p = 0.19 for AUC); c GLP-1 (p = 0.34 for AUC); d GIP (p = 0.09 for AUC); and e P-insulin (p = 0.19 for AUC). Data presented as mean ± SEM, p values are corrected for birthweight. *p < 0.05 between genotypes at indicated times. Broken lines with white triangles, risk allele carriers (n = 22); continuous lines with black circles, wild-type participants (n = 25)

Hyperglycaemic clamps with co-infusion of GLP-1 or GIP

The first-phase insulin response (0–20 min) was similar between risk allele carriers and non-carriers during GLP-1 as well as during GIP infusion (Fig. 5). In contrast, the ISRs were significantly reduced in carriers of the T allele during GLP-1 infusion at 75 and 90 min, and overall in the late phase (AUC20–120 CT/TT: 1,068 ± 79 vs CC: 1,323 ± 78; p = 0.03). During infusion of GIP, ISRs were significantly reduced at 15, 60 and 65 min and also tended to be reduced during the late phase of GIP infusion (AUC20–120 CT/TT: 630 ± 36 vs CC: 722 ± 33; p = 0.07), indicating reduced insulinotropic effects of both GLP-1 and GIP.

Hyperglycaemic clamps (7 mmol/l) with infusion of GLP-1 (a, c, e) or GIP (b, d, f). a, b Plasma (P) glucose; c, d P-insulin; and ISRs during infusion of e GLP-1 (p = 0.03 for 20 to 120 min) or f GIP (p = 0.07 for 20 to 120 min). Glucose infusion was initiated at −30 min, and GLP1 or GIP bolus given at −2 min. GLP1 or GIP co-infusion began at 0 min. Data presented as mean ± SEM, p values are corrected for birthweight. *p < 0.05 between genotypes at indicated times. Broken lines with white triangles, risk allele carriers (n = 22); continuous lines with black circles, wild-type participants (n = 25)

Prohormones

To address the hypothesis of malfunctioning prohormone convertase (PC) 1 and 2 in risk allele carriers, we performed post hoc analysis of the prohormones in the fasting state in all 81 individuals (Table 1). While plasma proinsulin levels were similar, plasma insulin was decreased and consequently the ratio of proinsulin:insulin increased in carriers of the risk T allele (CT/TT: 0.22 ± 0.02 vs CC: 0.17 ± 0.01; p = 0.014). However, the ratio of proglucagon/glucagon was not clearly affected by genotype (CT/TT: 3.44 ± 0.12 vs CC: 3.25 ± 0.11; p = 0.259).

Discussion

The novel findings in this study include reduced insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 as well as reduced beta cell responsiveness to glucose during a meal test in risk allele carriers of TCF7L2 rs7903146 among 47 young glucose-tolerant Danish men. In a similar group of 34 young healthy men, carriers of the risk T allele were characterised by elevated endogenous (hepatic) glucose production (EGP) as well as reduced 24 h circulating plasma insulin and plasma glucagon levels.

The major strength of this study is the detailed and extensive in vivo physiological phenotyping of a homozygous group of young white men, allowing us to document a number of metabolic abnormalities linking carriers of the T allele of rs7903146 to increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Conversely, an evident weakness is the relatively low number of study participants when seen in a genetic and epidemiological perspective.

Reduced insulin secretion associated with TCF7L2 polymorphisms may be mediated through multiple different mechanisms. Transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) is present in human islet cells [11, 26, 27] and animal studies have found that it directly regulates insulin secretion [27]. TCF7L2 operates in conjunction with β-catenin as a transcription factor to activate the expression of wingless-type MMTV integration site family member 2 (WNT)-signalling target genes. The WNT signalling pathway is involved in cell differentiation, beta cell proliferation [28] and insulin secretion [29]. The proglucagon gene is transcriptionally regulated by TCF7L2 and proglucagon is processed to GLP-1 in the L-cells of the intestines. Besides its insulinotropic effect, recent studies have shown that GLP-1 induces Wnt signalling in the beta cell and that WNT signalling appears to mediate GLP-1-induced beta cell proliferation [30]. Two studies have already provided evidence of an incretin-mediated insulin secretion defect in carriers of the risk allele [11, 12]. Our data expand on current knowledge by unmasking a robust early-onset beta cell hypo-responsiveness to GLP-1 in a young, healthy, glucose-tolerant population at much lower plasma glucose (7 mmol/l) using high physiological GLP-1 levels. Furthermore, we found a borderline significant reduction of insulin secretion during hyperglycaemic clamps with co-infusion of GIP in carriers of the risk T allele. Our differential findings of reduced late-, but not initial-phase insulin secretion in the carriers of the T alleles in response to both incretin hormones indicate that the acute release of insulin from the readily releasable granules docked on or in close proximity to the plasma membrane is intact, while the subsequent second phase of insulin release primarily derived from stored secretory granules and de novo insulin synthesis is impaired during GLP-1, and to some extent also GIP administration. The extent to which the impaired insulinotropic effect of GLP-1 may be due to acute intrinsic abnormalities, central effects or even mediated through reduced beta cell proliferation very early in life remains to be elucidated.

Theoretically, insulin secretion should be corrected for in vivo insulin sensitivity by calculating the disposition index, thereby accounting for the inverse relationship between insulin secretion and action in non-diabetic participants. Interestingly, the sensitivity and responsiveness of pancreatic insulin secretion to glucose during meal tests (i.e. the beta index) remained significantly reduced after correction for insulin action in carriers of the T allele of rs7903146 TCF7L2, supporting the notion of a true functional defect of pancreatic insulin secretion.

Most studies of patients with overt type 2 diabetes report elevated plasma glucagon levels compared with non-diabetic controls [15, 31]. Thus, our finding of lower, and not of elevated plasma glucagon levels during 24 h profiles in carriers of the T allele genotype may appear somewhat paradoxical. On the other hand TCF7L2 is also a transcription factor of the proglucagon gene and proglucagon is processed to glucagon in alpha cells [32]. Reduced expression of proglucagon in the alpha cells or altered posttranslational processing to glucagon could explain our findings of reduced plasma glucagon levels during 24 h profiles. Furthermore, it is possible that the apparent insulin secretion defect may be enhanced by impaired paracrine glucagon stimulation of the beta cells [33, 34]. Finally, the novel idea that TCF7L2 is involved in the control of plasma glucagon levels is supported by unpublished data (V. Lyssenko and L. Groop) from 580 non-diabetic individuals participating in the Prevalence–Prediction–Prevention study, in which two other single nucleotide polymorphisms of TCF7L2, including rs10885414 and rs4639863 (but not rs7903146), were associated with altered plasma glucagon levels (p = 0.03 and p = 0.02, respectively).

Two other recent studies reported a disproportionately increased basal rate of EGP and hepatic insulin resistance in carriers of the risk T allele of rs7903146 [11, 35]. Expanding on those recent findings, we found the absolute rate of EGP to be elevated in the basal state as well as during a high physiological insulin infusion in carriers of the risk T allele. While the elevated basal rate of EGP may be due to relatively lower endogenous ‘portal’ insulin secretion, this may not explain the elevated rate of EGP during clamp insulin infusions. Notably, the reduced diurnal plasma glucagon profiles were found in exactly the same participants with a documented elevated rate of EGP, so the increased EGP was not driven by elevated plasma glucagon levels. Studies in two MODY genotypes, HNF-1α/β (also known as HNF1A/B), have reported differential effects of HNF-1β and HNF-1α on hepatic insulin sensitivity, with normal plasma glucagon levels and unaffected peripheral insulin sensitivity, and it has been proposed that the site of defect is located in the regulation of insulin action by HNF-1β and its effect on gluconeogenesis [36]. Intra-cerebral administration of a GLP-1 receptor agonist caused a fourfold increase in insulin secretion and enhanced liver glycogen storage in mice [37]. It remains to be determined whether TCF7L2 exerts a direct or indirect (via the central nervous system) influence on hepatic gluconeogenesis, glycogenolysis and/or glycogen synthesis, explaining its effect on EGP in the basal state as well as during insulin infusion.

In accordance with findings from Loos et al. [10], we found an increased ratio of proinsulin/insulin, which was primarily due to relatively reduced insulin levels as opposed to elevated proinsulin levels as such. We saw no impact of genotype on the proglucagon/glucagons ratio. PC1 and PC2 are differentially synthesised in various endocrine cell lines and give rise to a varied mixture of peptide products [38]. It can be hypothesised that carriers of the risk T allele have a specific impairment in PC1, which is more greatly involved in post-translational insulin processing than PC2, which has been shown to account for the majority of proglucagon processing in the alpha cells [39]. GLP-1 is processed from proglucagon by PC1 in the L-cells. Schäfer et al. reported unaffected levels of GLP-1 in response to an OGTT in risk allele carriers [12]. In this study, GLP-1 levels were non-significantly lower in carriers of the T allele of the TCF7L2 genotype, and additional studies will be required to provide conclusive results concerning the impact of this genotype on GLP-1 secretion.

In conclusion, we report that in two populations of young, healthy, glucose-tolerant men, carriers of the risk T allele of rs7903146 TCF7L2 had significantly elevated HbA1c as well as reduced fasting/postabsorptive and postprandial insulin concentrations during the course of a standardised 24 h period. The T allele was associated with reduced beta cell responsiveness to a mixed meal and diminished incretin effect as evidenced by reduced late-phase beta cell responsiveness to GLP-1. The finding of elevated EGP in the basal state and during insulin infusion in the face of paradoxically reduced plasma glucagon levels in carriers of the T allele indicates either a more direct role of TCF7L2 in the regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism or a potential indirect effect on hepatic glucose metabolism operating via the central nervous system.

Abbreviations

- EGP:

-

Endogenous glucose production

- FFM:

-

Fat-free mass

- GIP:

-

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

- GLP:

-

Glucagon-like peptide

- ISR:

-

Insulin secretion rate

- PC:

-

Prohormone convertase

- TCF7L2:

-

Transcription factor 7-like 2

References

Chandak GR, Janipalli CS, Bhaskar S et al (2007) Common variants in the TCF7L2 gene are strongly associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Indian population. Diabetologia 50:63–67

Florez JC, Jablonski KA, Bayley N et al (2006) TCF7L2 polymorphisms and progression to diabetes in the Diabetes Prevention Program. N Engl J Med 355:241–250

Grant SFA, Thorleifsson G, Reynisdottir I et al (2006) Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene confers risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 38:320–323

Helgason A, Palsson S, Thorleifsson G et al (2007) Refining the impact of TCF7L2 gene variants on type 2 diabetes and adaptive evolution. Nat Genet 39:218–225

Horikoshi M, Hara K, Ito C, Nagai R, Froguel P, Kadowaki T (2007) A genetic variation of the transcription factor 7-like 2 gene is associated with risk of type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetologia 50:747–751

Mayans S, Lackovic K, Lindgren P et al (2007) TCF7L2 polymorphisms are associated with type 2 diabetes in northern Sweden. Eur J Hum Genet 15:342–346

van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Shiri-Sverdlov R, Zhernakova A et al (2007) Association of variants of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) with susceptibility to type 2 diabetes in the Dutch Breda cohort. Diabetologia 50:59–62

Zhang CL, Qi L, Hunter DJ et al (2006) Variant of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene and the risk of type 2 diabetes in large cohorts of US women and men. Diabetes 55:2645–2648

Cauchi S, El AY, Choquet H et al (2007) TCF7L2 is reproducibly associated with type 2 diabetes in various ethnic groups: a global meta-analysis. J Mol Med (Berlin) 85:777–782

Loos RJF, Franks PW, Francis RW et al (2007) TCF7L2 polymorphisms modulate proinsulin levels and beta-cell function in a British Europid population. Diabetes 56:1943–1947

Lyssenko V, Lupi R, Marchetti P et al (2007) Mechanisms by which common variants in the TCF7L2 gene increase risk of type 2 diabetes. J Clin Invest 117:2155–2163

Schäfer SA, Tschritter O, Machicao F et al (2007) Impaired glucagon-like peptide-1-induced insulin secretion in carriers of transcription factor 7-like 2 (TCF7L2) gene polymorphisms. Diabetologia 50:2443–2450

Nauck MA, Meier JJ (2007) The enteroinsular axis may mediate the diabetogenic effects of TCF7L2 polymorphisms. Diabetologia 50:2413–2416

Yi F, Brubaker PL, Jin T (2005) TCF-4 mediates cell type-specific regulation of proglucagon gene expression by beta-catenin and glycogen synthase kinase-3beta. J Biol Chem 280:1457–1464

Unger RH (1970) Studies of pancreatic alpha cell function in normal and diabetic subjects. J Clin Invest 49:837–848

Vaag AA, Holst JJ, Volund A, Beck-Nielsen H (1996) Gut incretin hormones in identical twins discordant for non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM)-evidence for decreased glucagon-like peptide 1 secretion during oral glucose ingestion in NIDDM twins. Eur J Endocrinol 135:425–432

Nauck MA, Heimesaat MM, Orskov C, Holst JJ, Ebert R, Creutzfeldt W (1993) Preserved incretin activity of glucagon-like peptide-1 (7-36-amide) but not of synthetic human gastric inhibitory polypeptide in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 91:301–307

Vilsbøll T, Krarup T, Madsbad S, Holst JJ (2002) Defective amplification of the late phase insulin response to glucose by GIP in obese type II diabetic patients. Diabetologia 45:1111–1119

Jensen CB, Storgaard H, Dela F, Holst JJ, Madsbad S, Vaag AA (2002) Early differential defects of insulin secretion and action in 19-year-old Caucasian men who had low birth weight. Diabetes 51:1271–1280

Schou JH, Pilgaard K, Vilsbøll T et al (2005) Normal secretion and action of the gut incretin hormones glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide in young men with low birth weight. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:4912–4919

Freathy RM, Weedon MN, Bennett A et al (2007) Type 2 diabetes TCF7L2 risk genotypes alter birth weight: A study of 24,053 individuals. Am J Hum Genet 80:1150–1161

Kjems LL, Roder ME, Dinesen B, Hartling SG, Jorgensen PN, Binder C (1993) Highly sensitive enzyme immunoassay of proinsulin immunoreactivity with use of two monoclonal antibodies. Clin Chem 39:2146–2150

Holst JJ (1982) Evidence that enteroglucagon (II) is identical with the C-terminal sequence (residues 33–69) of glicentin. Biochem J 207:381–388

Hovorka R, Koukkou E, Southerden D, Powrie JK, Young MA (1998) Measuring prehepatic insulin secretion using a population model of C-peptide kinetics: Accuracy and required sampling schedule. Diabetologia 41:548–554

Kjems LL, Volund A, Madsbad S (2001) Quantification of beta-cell function during IVGTT in type II and non-diabetic subjects: Assessment of insulin secretion by mathematical methods. Diabetologia 44:1339–1348

Cauchi S, Meyre D, Dina C et al (2006) Transcription factor TCF7L2 genetic study in the French population—expression in human beta-cells and adipose tissue and strong association with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 55:2903–2908

Loder MK, Xavier GDS, McDonald A, Rutter GA (2008) TCF7L2 controls insulin gene expression and insulin secretion in mature pancreatic β-cells. Biochem Soc Trans 36:357–359

Rulifson IC, Karnik SK, Heiser PW et al (2007) Wnt signaling regulates pancreatic beta cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:6247–6252

Smith U (2007) TCF7L2 and type 2 diabetes—we WNT to know. Diabetologia 50:5–7

Liu ZY, Habener JF (2008) Glucagon-like peptide-1 activation of TCF7L2-dependent Wnt signaling enhances pancreatic beta cell proliferation. J Biol Chem 283:8723–8735

Unger RH, Orci L (1977) Role of glucagon in diabetes. Arch Intern Med 137:482–491

Fehmann HC, Goke R, Goke B (1995) Cell and molecular-biology of the incretin hormones glucagon- like peptide-i and glucose-dependent insulin releasing polypeptide. Endocr Rev 16:390–410

Huypens P, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Schuit F (2000) Glucagon receptors on human islet cells contribute to glucose competence of insulin release. Diabetologia 43:1012–1019

Sørensen H, Winzell MS, Brand CL et al (2006) Glucagon receptor knockout mice display increased insulin sensitivity and impaired beta-cell function. Diabetes 55:3463–3469

Wegner L, Hussain MS, Pilgaard K et al (2008) Impact of TCF7L2 rs7903146 on insulin secretion and action in young and elderly Danish twins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:4013–4019

Brackenridge A, Pearson ER, Shojaee-Moradie F, Hattersley AT, Russell-Jones D, Umpleby AM (2006) Contrasting insulin sensitivity of endogenous glucose production rate in subjects with hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta and -1 alpha mutations. Diabetes 55:405–411

Knauf C, Cani PD, Perrin C et al (2005) Brain glucagon-like peptide-1 increases insulin secretion and muscle insulin resistance to favor hepatic glycogen storage. J Clin Invest 115:3554–3563

Rouille Y, Martin S, Steiner DF (1995) Differential processing of proglucagon by the subtilisin-like prohormone convertases pc2 and pc3 to generate either glucagon or glucagon-like peptide. J Biol Chem 270:26488–26496

Rouille Y, Westermark G, Martin SK, Steiner DF (1994) Proglucagon is processed to glucagon by prohormone convertase PC2 in alpha TC1-6 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:3242–3246

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the volunteers for their participation in the project. We also wish to acknowledge the outstanding technical assistance provided by M. Modest and S. Reimer. The study was supported by the Danish Diabetes Association. Work in Malmö was supported by an EFSD grant (to V. Lyssenko) and a grant from the Swedish Research Council (to L. Groop).

Duality of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Text

(PDF 50.9 KB)

ESM Table 1

Euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp (PDF 129 KB)

ESM Table 2

Characteristics of study participants categorised by groups (PDF 89.6 KB)

Fig. 1

Euglycaemic–hyperinsulinaemic clamp. Data from the last 30 min of basal, low-insulin and high-insulin period for a plasma (P) glucose, b P-insulin and c P-glucagon. *p < 0.05. White triangles, risk T-allele carriers (n = 15); black circles, wild-type participants (n = 19) (PDF 12.1 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pilgaard, K., Jensen, C.B., Schou, J.H. et al. The T allele of rs7903146 TCF7L2 is associated with impaired insulinotropic action of incretin hormones, reduced 24 h profiles of plasma insulin and glucagon, and increased hepatic glucose production in young healthy men. Diabetologia 52, 1298–1307 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1307-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-009-1307-x