Abstract

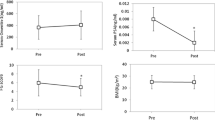

Background/aims: Prostatic specific antigen (PSA) is the most specific prostatic tumor marker in man. Recently, PSA has been detected in a variety of tissues and fluids in women, and its determination suggested as a marker of hyperandrogenism. However, precise information about the physiology of PSA in females is not available. The goal of this study was to assess serum concentrations of PSA in healthy pre-menopausal women (healthy pre-menopausal group), menopausal women (menopause group) and patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS group). Methods: PSA, androgens, LH, FSH, 17-β-estradiol (E2), progesterone (Pg) were assessed in 40 post-menopausal women, 35 fertile controls and 35 women with PCOS. Results: No significant difference in PSA concentrations could be demonstrated in different phases of the menstrual cycle in healthy pre-menopausal group and between pre- and post-menopausal groups. No correlations could be demonstrated between serum PSA levels and the following parameters: age, body mass index (BMI), LH, FSH, E2, testosterone (T), DHEAS, and SHBG, both in pre- and post-menopausal women. Significantly higher PSA levels (median=14 pg/ml) were found in the PCOS group compared to both pre-menopausal (median=5 pg/ml) and menopausal (median= 5 pg/ml) groups (p<0.05). Conclusions: only minor fluctuations of serum PSA concentrations are observed in healthy pre- and post-menopausal women, while serum level is higher in PCOS, and therefore PSA can be considered a suitable marker of female hyperandrogenism.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Clements JA. The glandular kallicrein family of enzymes. Tissue-specific expression and hormonal regulation. Endocr Rev 1989, 10: 393–419.

Hara M, Koyanagi Y, Inoue T, et al. Some physico-chemical characteristic of gamma-“seminoprotein” and antigenic component specific for human seminal plasma. Nippon Hoigaku Zasshi 1971, 25: 322–4.

Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ratiff DL, et al. Measurement of prostate-specific antigen in serum as a screening test for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 1991, 17: 1156–61.

Clements JA. The human kallicrein gene family: a diversity of expression and function. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1994, 99: C1–6.

Tepper SL, Jagirdar J, Heath D, Geller SA. Homology between the female parauretral (Skene’s) glands the prostate. Immunohistochemical demonstration. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984, 108: 423–5.

Flamini MA, Barbeito CG, Gimeno EJ, et al. Morphological characterization of the female prostate (Skene gland or paraurethral gland) of Lagostomus maximus maximus. Ann Anat 2002, 184: 341–5.

Luke MC, Coffey DS. Human androgen receptor binding to the androgen response element of prostate specific antigen. J Androl 1994, 15: 41–51.

Yu H, Diamandis EP, Monne M, et al. Oral contraceptive-induced expression of prostate-specific antigen in the female breast. J Biol Chem 1995, 270: 6615–8.

Diamandis EP, Yu H. Non prostatic sources of prostate-specific antigen. Urol clin North Am 1997, 24: 275–82.

Yu H, Diamandis EP, Levesque M, et al. Expression of the prostate-specific antigen gene by a primary ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res 1995, 1555: 1603–6.

Majumdar S, Diamandis EP. The promoter and the enhancer region of the KLK 3 (prostate specific antigen) gene is frequently mutated in breast tumours and in breast carcinoma cell lines. Br J Cancer 1999, 79: 1594–602.

Zarghami N, Grass L, Diamandis EP. Steroid hormone regulation of prostate-specific antigen gene expression in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1997, 75: 579–88.

Melegos DN, Yu H, Ashok M, et al. Prostate-specific antigen in female serum, a potential new marker of androgen excess. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82: 777–80.

Negri C., Tosi F., Dorizzi R., et al. Antiandrogen drugs lower serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels in hirsute subjects: evidence that serum PSA is a marker of androgen action in woman. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000, 85: 81–4.

Escobar-Morreale HF, Serrano-Gotarredona J, Avila S, et al. The increased circulating prostate-specific antigen concentrations in women with hirsutism do not respond to acute changes in adrenal or ovarian function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998, 83: 2580–4.

Escobar-Morreale HF, Avila S, Sancho J, et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen concentrations are not useful for moni-toring the treatment of hirsutism with oral contraceptive pills. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000, 85: 2488–92.

Zarghami N, Grass L, Sauter ER, et al. Prostate-specific antigen in serum during the menstrual cycle. Clin Chem 1997, 43: 1862–7.

Aksoy H, Akcay F, Umudum Z, et al. Changes of PSA concentrations in serum and saliva of healthy women during the menstrual cycle. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2002, 32: 31–6.

Jongen VH, Shuijmer AV, Heineman MU. The postmeno-pausal ovary as an androgen-producing gland; hypothesis on the etiology of endometrial cancer. Maturitas 2002, 43: 77–85.

Ferriman D, Gallwey JD. Clinical assessment of body hair growth in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1961, 21: 1440–7.

The Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 2004, 19: 41–7.

Mitchell G, Sibley PE, Wilson AP, etal. Prostate-specific antigen in nipple aspiration fluid. Menstrual cycle variability and correlation with serum prostate specific antigen. Tumour Biol 2002, 23: 287–97.

Couzinet B, Meduri G, Glecce M, et al. The post-menopausal ovary is not a major androgen-producing gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001, 86: 5060–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burelli, A., Cionini, R., Rinaldi, E. et al. Serum PSA levels are not affected by the menstrual cycle or the menopause, but are increased in subjects with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 29, 308–312 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03344101

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03344101