Abstract

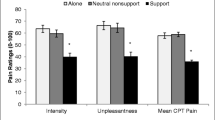

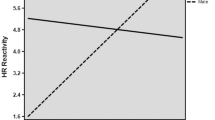

Background: Gender differences in coronary heart disease are mirrored by gender differences both in cardiovascular reactivity to stress and in the nature and content of social support networks. However, little research has examined the association between cardiovascular reactivity in the laboratory and social support outside; and none has established whether gender differences in such associations can elucidate relevant psychosomatic mechanisms. In addition, in general, studies of cardiovascular reactivity fail to take adequate account of cardiovascular response habituation.Purpose: The present study sought to examine gender differences in associations between psychometrically assessed social support and cardiovascular reactivity and, in particular, response habituation patterns.Method: Ninety-two undergraduate men and women underwent two consecutive cardiovascular reactivity assessments, after having provided psychometric assessments of quantity and quality of social support in ordinary life.Results: Inverse associations between social support and cardiovascular reactivity during the second assessment suggested that highly-supported women exhibited cardiovascular response habituation. For men, the opposite trend—that of support-related cardiovascular sensitization—was found. Results were unaffected by performance of the task used to elicit reactivity or by participant ratings of task dimensions.Conclusions: These findings suggest that men and women differ in the degree to which social support in ordinary life moderates cardiovascular stress responses in laboratories. This difference is highlighted when looking at how cardiovascular responses fluctuate over repeated testing. Habituation-sensitization patterns suggest that, when dealing with difficult tasks, women may derive benefit from background social relationships whereas men may find that such background relationships bring additional pressures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rutter A, Hine DW: Sex differences in workplace aggression: An investigation of moderation and mediation effects.Aggressive Behavior. 2005,31:254–270.

Weidner G, Cain VS: The gender gap in heart disease: Lessons from Eastern Europe.American Journal of Public Health. 2003,93:768–770.

Inaba A, Thoits PA, Ueno K, et al.: Depression in the United States and Japan: Gender, marital status, and SES patterns.Social Science & Medicine. 2005,61:2280–2292.

Linden W, Gerin W, Davidson K: Cardiovascular reactivity: Status quo and a research agenda for the new millennium.Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003,65:5–8.

Lovallo WR, Gerin W: Psychophysiological reactivity: Mechanisms and pathways to cardiovascular disease.Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003,65:36–45.

Schwartz AR, Gerin W, Davidson KW, et al.: Toward a causal model of cardiovascular responses to stress and the development of cardiovascular disease.Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003,65:22–35.

Treiber FA, Kamarck T, Schneiderman N, et al.: Cardiovascular reactivity and development of preclinical and clinical disease states.Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003,65:46–62.

Light KC, Turner JR, Hinderliter A, Sherwood A: Race and gender comparisons: I. Hemodynamic responses to a series of stressors.Health Psychology. 1993,12:354–365.

Newton TL, Watters CA, Philhower CL, Weigel RA: Cardiovascular reactivity during dyadic social interaction: The roles of gender and dominance.International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2005,57:219–228.

Sarlo M, Palomba D, Buodo G, Minghetti R, Stegagno L: Blood pressure changes highlight gender differences in emotional reactivity to arousing pictures.Biological Psychology. 2005,70:188–196.

Stoney CM, Davis MC, Matthews KA: Sex differences in physiological responses to stress and in coronary heart disease: A causal link?Psychophysiology. 1987,24:127–131.

Cohen S: Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease.Health Psychology. 1988,7:269–297.

Eriksen W: The role of social support in the pathogenesis of coronary heart disease: A literature review.Family Practice. 1994,11:201–209.

House J, Landis SA, Umberson D: Social relationships and health.Science. 1988,241:540–545.

Thorsteinsson EB, James JE: A meta-analysis of the effects of experimental manipulations of social support during laboratory stress.Psychology & Health. 1999,14:869–886.

Kors DJ, Linden W, Gerin W: Evaluation interferes with social support: Effects on cardiovascular stress reactivity in women.Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1997,16:1–23.

Thorsteinsson EB, James JE, Gregg ME: Effects of video-relayed social support on hemodynamic reactivity and salivary cortisol during laboratory-based behavioral challenge.Health Psychology. 1998,17:436–444.

Lepore SJ: Cynicism, social support, and cardiovascular reactivity.Health Psychology. 1995,14:210–216.

Gerin W, Milner D, Chawla S, Pickering TG: Social support as a moderator of cardiovascular reactivity in women: A test of the direct effects and buffering hypotheses.Psychosomatic Medicine. 1995,57:16–22.

Sheffield D, Carroll D: Social support and cardiovascular reactions to active laboratory stressors.Psychology & Health. 1994,9:305–316.

Uchino BN, Garvey TS: The availability of social support reduces cardiovascular reactivity to acute psychological stress.Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997,20:15–27.

Hughes BM: Research on psychometrically evaluated social support and cardiovascular reactivity to stress: Accumulated findings and implications.Studia Psychologica. 2002,44:311–326.

Janicki DL, Kamarck TW, Shiffman S, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Gwaltney CJ: Frequency of spousal interaction and 3-year progression of carotid artery intima medial thickness: The Pittsburgh Healthy Heart Project.Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005,67:889–896.

Hughes B, Curtis R: Quality and quantity of social support as differential predictors of cardiovascular reactivity.Irish Journal of Psychology. 2000,21:16–31.

Roy MP, Steptoe A, Kirschbaum C: Life events and social support as moderators of individual differences in cardiovascular and cortisol reactivity.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998,75:1273–1281.

Väänänen A, Buunk BP, Kivimäki M, Pentti J, Vahtera, J: When it is better to give than to receive: Long-term health effects of perceived reciprocity in support exchange.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005,89:176–193.

Van Emmerik IJH: Gender differences in the creation of different types of social capital: A multilevel study.Social Networks. 2006,28:24–37.

Bellman S, Forster N, Still L, Cooper CL: Gender differences in the use of social support as a moderator of occupational stress.Stress & Health. 2003,19:45–58.

Taylor SE, Klein LC, Lewis BP, et al.: Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight.Psychological Review. 2000,107:411–429.

Taylor SE:The Tending Instinct: How Nurturing Is Essential to Who We Are and How We Live. New York: Times Books, 2002.

Belle D: Gender differences in the social moderators of stress. In Barnett RC, Biener L, Baruch GK (eds),Gender and Stress. New York: Free Press, 1987, 257–277.

Copeland EP, Hess RS: Differences in young adolescents’ coping strategies based on gender and ethnicity.Journal of Early Adolescence. 1995,15:203–219.

Carter CS: Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love.Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998,23:779–818.

Geary DC, Flinn MV: Sex differences in behavioral and hormonal response to social threat: Commentary on Taylor et al. (2000).Psychological Review. 2002,109:745–750.

Kelsey RM: Electrodermal lability and myocardial reactivity to stress.Psychophysiology. 1991,28:619–631.

Carroll D, Cross G, Harris MG: Physiological activity during a prolonged mental stress task: Evidence for a shift in the control of pressor reactions.Journal of Psychophysiology. 1990,4:261–269.

Turner JR:Cardiovascular Reactivity and Stress: Patterns of Physiological Response. New York: Plenum, 1994.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The hospital anxiety and depression scale.Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983,67:361–370.

Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Shearin EN, Pierce GR: A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications.Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1987,4:497–510.

Jennings JR, Kamarck T, Stewart C, Eddy M, Johnson P: Alternate cardiovasuclar baseline assessment techniques: Vanilla or resting baseline.Psychophysiology. 1992,29:742–750.

Llabre MM, Spitzer SB, Saab PG, Ironson GH, Schneiderman N: The reliability and specificity of delta versus residualized change as measures of cardiovascular reactivity to behavioural challenges.Psychophysiology. 1991,28:708–711.

Benjamin L: Facts and artifacts in using analysis of covariance to “undo” the law of initial values.Psychophysiology. 1967,4:187–206.

Williams RH, Zimmerman DW: Are simple gain scores obsolete?Applied Psychological Measurement. 1996,20:59–69.

Jamieson J: Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with difference scores.International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2004,52:277–283.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS:Using Multivariate Statistics (3rd ed.). New York: HarperCollins, 1989.

Cohen J:Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988.

Cohen J: A power primer.Psychological Bulletin. 1992,112:155–159.

Greenhouse SW, Geisser S: On methods in the analysis of profile data.Psychometrika. 1959,24:95–112.

Cohen S, Wills TA: Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis.Psychological Bulletin. 1985,98:310–357.

Bassett JR, Cairncross KD: Changes in the coronary vascular system following prolonged exposure to stress.Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1977,6:311–318.

McCarty R, Horwatt K, Konarska M: Chronic stress and sympathetic-adrenal medullary responsiveness.Social Science & Medicine. 1988,26:333–341.

Kelsey RM: Habituation of cardiovascular reactivity to psychological stress: Evidence and implications. In Blascovich J, Katkin ES (eds),Cardiovascular Reactivity to Psychological Stress and Disease. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1993, 135–153.

Fleming I, Baum A, Davidson LM, Rectanus E, McArdle S: Chronic stress as a factor in physiologic reactivity to challenge.Health Psychology. 1987,6:221–237.

Konarska M, Stewart RE, McCarty R: Sensitization of sympathetic-adrenal medullary responses to a novel stressor in chronically stressed laboratory rats.Physiology & Behavior. 1989,46:129–135.

Carroll D, Cross G, Harris MG: Physiological activity during a prolonged mental stress task: Evidence for a shift in the control of pressor reactions.Journal of Psychophysiology. 1990,4:261–269.

Yamagishi H, Yoshiyama M, Shirai N, et al.: Protective effect of high diastolic blood pressure during exercise against exercise-induced myocardial ischemia.American Heart Journal. 2005,150:790–795.

Smith TW, Limon JP, Gallo LC, Ngu LQ: Interpersonal control and cardiovascular reactivity: Goals, behavioral expression, and the moderating effect of sex.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996,70:1012–1024.

Hughes BM, Callinan S: Trait dominance and cardiovascular reactivity to social and non-social stressors: Gender-specific implications.Psychology & Health. 2007,22:457–472.

James JE: Critical review of dietary caffeine and blood pressure: A relationship that should be taken more seriously.Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004,66:63–71.

Ehlers A, Mayou RA, Sprigings DC, Birkhead J: Psychological and perceptual factors associated with arrhythmias and benign palpitations.Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000,62:693–702.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

This study was supported by a Scientific Research Grant from the Irish Heart Foundation.

About this article

Cite this article

Hughes, B.M. Social support in ordinary life and laboratory measures of cardiovascular reactivity: gender differences in habituation-sensitization. ann. behav. med. 34, 166–176 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02872671

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02872671