Abstract

Background

Hypovitaminosis D is one of the hazardous factors for multiple sclerosis (MS) and can be attested by expanding clinical studies. We aimed to study vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene polymorphisms: FokI, BsmI, ApaI, TaqI, and Tru9I genotype; frequency; haplotype structure; and linkage disequilibrium (LD) in MS Egyptian patients. The study was conducted on 50 MS patients and 50 healthy controls of matching age and sex. Alleles and genotype variants of VDR gene SNPs were analyzed by PCR using the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). Haplotype and linkage disequilibrium analysis based on the five genetic loci was studied on the detected genotypes.

Results

Frequency of FokI genotype (Ff+ff) was significantly higher in healthy controls (50%) compared to MS (28%) (P = 0.03), and “f” allele was significantly associated with the control group (OR = 0.42, CI = 0.26–0.85, P = 0.015). Frequency of ApaI genotype (Aa+aa) was significantly higher in MS (60%) (P = 0.002), and “a” allele was significantly associated with MS cases (OR = 2.47, CI = 1.25–4.88, P = 0.008). TaqI allelic distribution showed significant association of “t” allele with control group (OR = 0.55, CI = 0.31–0.98, P = 0.04). Statistically significant LD was detected between BsmI and ApaI in controls and MS (D' = 0.89 and P < 0.001, and D' = 0.52 and P < 0.001), respectively. Odd ratios of “fAt” and “BAt” were 0.2 (95% CI = 0.06–0.66) and 0.43 (95% CI = 0.19–0.97), respectively, suggesting that MS risk was 5 times and 2.3 times lesser, respectively, for haplotype carriers compared to non-carriers.

Conclusion

The study findings suggest that VDR gene variants “f,” “A,” and “t” alleles as well as VDR gene haplotypes “BAt” and “fAt” may have a protective effect against MS disease in Egyptian population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an immunoinflammatory and neurodegenerative disease caused by autoimmune reaction to the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. These inflammatory insults result in MS symptoms such as optic nerve damage and motor difficulty [2]. MS is a multifactorial disease that is reliant on both genetic and environmental susceptibility [2,3,4]. In the perspective of substantial results from experimental work, reliable epidemiological information, and encouraging clinical findings, the theory that hypovitaminosis D as one of MS risk factors has quickly gained support and can, before long, be affirmed by more broad clinical studies. Vitamin D (VD) role in MS pathogenesis was highlighted in several studies that showed decreased level of active form of VD in initial and serious phases of MS [5,6,7,8]. Genetic variations in vitamin D receptor (VDR) gene as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) might alter VD-VDR pathway causing disturbance of VD immune-regulatory functions which consequently is reflected on MS risk [9,10,11,12]. Most of genomic studies in MS pathogenesis suggested that no single gene locus predisposed to MS disease and multiple genes may have an impact on MS pathogenesis, risk, and presentation. The currently studied VDR polymorphisms include FokI polymorphism (rs10735810) in the 5′ promoter area and are referred to as start codon polymorphism (SCP) [13]. Presence of FokI restriction enzyme site results in the variant “f” allele and translation of a 3 amino acid longer VDR protein, while the “F” allele, the wild type, produces shorter VDR protein and is associated with an increased transcriptional activity [13]. Other VDR SNPs are located in the 3′UTR and defined by the restriction enzymes as BsmI polymorphism (rs1544410) A/G in intron 8, ApaI polymorphism (rs7975232) G/T in intron 8, TaqI polymorphism (rs731236) T/C in exon 9, and Tru9I polymorphism (rs757343) G/A in intron 8 [6,7,8, 14,15,16,17,18]. Considering each SNP site independently may not uncover critical impacts or clarify variations of numerous endeavors to associate VDR genotype with MS [7, 19,20,21,22]. Hence, our aim was to study the genotype and frequency of VDR gene polymorphisms: FokI, BsmI, ApaI, TaqI, and Tru9I, in MS Egyptian patients. Additionally, we analyzed the haplotype structure and possible genetic linkage disequilibrium (LD) of the studied loci. To our knowledge, no previous studies have covered those genetic aspects in MS Egyptian population, and we believe it may help in establishing clinical registries for future studies.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

One hundred subjects were recruited in this study and divided into 2 groups: group I, 50 MS patients that were diagnosed according to McDonald criteria [23], and group II, 50 healthy subjects of matching age and sex were included as a control group. All patients were subjected to thorough history taking, clinical, and neurological examination. The study has been carried out following the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, in accordance with Helsinki Declaration (reference number: 0101952). Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

VDR gene polymorphisms genotyping by PCR-RFLP

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA-peripheral blood samples obtained from both groups using Thermo Scientific GeneJET Whole Blood Genomic DNA Purification Mini Kit (USA #K0781) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The extracted DNA was stored at − 20 °C till used. The targeted SNP was identified by PCR-RFLP where the targeted SNP was amplified by conventional PCR followed by restriction digestion. SNP primer sequences, PCR thermal profiles, and expected amplicon size following restriction digestion are summarized in Table 1. All VDR polymorphisms were named according to their corresponding restriction enzymes, using the commonly used BAT nomenclature of VDR (NCBI official nomenclature, reference sequence AY342401.1, GI:32891816) [24]. The presence of the restriction site was indicated with small letters, and its absence was indicated with capital letters. Only in Tru9I, its presence was indicated by “u” letter and absence by “U” (Table 2).

PCR-RFLP reactions were performed in a 50-μl final volume; 25 μl Thermo Scientific Dream Taq green PCR master mix, 2 μl of forward and reverse SNP primers (Sigma Aldrich, USA), 10 μl genomic DNA, and 11 μl DNase-free water and PCR protocols designed to the corresponding SNP were applied as in Table 1. The amplicons were examined by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis to ensure appropriate amplification. The amplified PCR products were digested using the corresponding restriction enzymes, and the resulted RFLP products were analyzed by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by Dolphin-Doc gel documentation system (Wealtec, USA). The restriction enzyme mixture reaction was 30 μl final volume and contained 17 μl nuclease-free water, 2 μl 10X FastDigest green buffer, 10 μl PCR product, and 1 μl FastDigest enzyme. Restriction enzymes were used following the manufacturer’s instructions: FokI code number: #FD2144, BsmI code number: #FD0964, Tru9I code number #FD0984, ApaI code number #FD1414, and TaqI code number: #FD0674 (Thermo Scientific FastDigest, USA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software package version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Odds ratios (OR) are given with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Qualitative data were analyzed using the chi-square test and Monte Carlo to compare different groups. Normally distributed quantitative data were analyzed using Student’s t test. Parametric quantitative data were expressed using mean and standard deviation. P value was assumed to be significant at ≤ 0.05. Haplotype frequencies and distribution study were conducted using Haploview 4.2 software, and haplotypes were assembled as different combinations of the five VDR SNPs. Normalized linkage disequilibrium coefficient D′ (D′)[25] values range from − 1 to 1, and values close to − 1 or 1 indicate high polymorphism linkage on one allele and were calculated using SPSS software [26].

Results

Demographic data

The studied cases were divided into group I (MS patients; n = 50, 22 males (44%) and 28 females (56%), age range 18–50 years (mean 30 ± 8 years)) and group II (healthy controls; n = 50, 18 males (36%) and females 32 (64%), age range 17–55 years (mean 32 ± 11 years)). Demographically, among MS patients, females were presented more than males with percentage of 56%. Studied MS patients were categorized according to clinical and neurological examination into relapsing/remitting MS (RRMS) which is characterized by clearly discrete attacks with neurological stability between attacks (n = 44 (88%)) and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) which usually starts as RRMS with progressive worsening of neurologic function (n = 6 (12%)), while primary progressive MS (PPMS) which is characterized by deteriorating neurologic function from the onset of symptoms without acute attacks or progressive relapsing MS (PRMS) which is characterized by steady functional deterioration with occasional attacks had no presentation among studied MS cases.

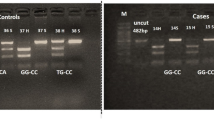

VDR gene polymorphism genotype and allelic distribution (Fig. 1, Table 2)

VDR gene polymorphisms were genotyped for all studied subjects, and the resulted RFLP products were visualized by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 1). Distribution of FokI, BsmI, ApaI, TaqI, and Tru9I genotypes with the respective allele frequencies and associations was analyzed in MS and controls (Table 2).

-

1.

FokI genotype distribution in MS was as follows: FF (wild) = 72%, Ff (heterozygous) = 28%, and ff (mutant) = 0%, while in controls: FF = 50%, Ff = 44%, and ff = 6%. FokI genotype (Ff+ff) percentage was higher in controls 50% vs MS case 28% (P = 0.029) (Table 2). There was a statistically significant association of “f” allele with the control group compared to MS cases (OR = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.26–0.85, P = 0.015) (Table 2).

-

2.

BsmI genotype distribution in MS was as follows: BB (mutant) = 40%, Bb (heterozygous) = 24%, and bb (wild) = 36%, while in controls: BB = 44%, Bb = 30%, and bb = 26%. No statistically significant difference was detected between MS cases vs controls with respect to BsmI genotype or allelic distribution (Table 2).

-

3.

ApaI genotype distribution in MS was as follows: AA (mutant) = 40%, Aa (heterozygous) = 56%, and aa (wild) = 4%, while in controls: AA = 72%, Aa = 24%, and aa = 4%. ApaI genotype (Aa+aa) percentage was higher in MS cases 60% vs control group 28% (P = 0.002) (Table 2). Statistically significant association was detected between “a” allele and MS cases (OR = 2.47, 95% CI = 1.25–4.88, P = 0.008) Table 2.

-

4.

TaqI genotype distribution in MS was as follows: TT (wild) = 48%, Tt (heterozygous) = 40%, and tt (mutant) = 12%, while in controls: TT = 36%, Tt = 36%, and tt = 28%. No statistically significant difference was detected between MS cases vs controls with respect to TaqI genotype distribution (Table 2). However, there was a statistically significant association of “t” allele with the control group (OR = 0.55, CI = 0.31–0.98, P = 0.042) (Table 2).

-

5.

Tru9I genotype distribution in MS was as follows: UU (wild) = 56%, Uu (heterozygous) = 40%, and uu (mutant) = 4%, while in controls: UU = 74%, Uu = 20%, and uu = 6%. No statistically significant difference was detected between MS cases and controls with respect to Tru9I genotype or allelic distribution (Table 2).

PCR-RFLP based genotyping of VDR gene polymorphisms. VDR SNP was genotyped by PCR-RFLP (described in methodology), and the RFLP bands were visualized by 3% agarose gel electrophoresis. a FokI: lane 1: FF, lane 2: Ff, and lane 3: ff. b BsmI: lane 1: BB, lane 2, 4: bb, and lane 3: Bb. c ApaI: lane 1, 2: aa, lane 3, 4: Aa, and lane 5, 6: AA. d TaqI: lane 1: tt, lane 2: TT, and lane 3: Tt. e Tru9I: lane 1: Uu, lane 2: UU, lane 3, 4: uu, and lane 5, 6: DNA from lanes 3 and 4 were reloaded on 5% agarose gel for better resolution. DM, 100 bps DNA marker, size of the band in bps is written above the corresponding band with white arrowhead. VDR SNPs genotypes with the expected RFLP bands are summarized in a table (right-hand side)

Haplotype analysis

In controls; haplotype analysis revealed statistically significant pairwise LD between FokI/ApaI (D′ = 0.39, P = 0.012), FokI/TaqI (D′ = 0.47, P = 0.002), BsmI/ApaI (D′ = 0.89, P < 0.001), and BsmI/TaqI (D′ = − 0.26, P = 0.017) (Table 3). While in MS cases, statistically significant pairwise LD was detected between BsmI/ApaI(D′ = 0.52, P < 0.001) and Tru9I/ApaI (D′ = 0.26, P = 0.03) (Table 3). Haplotype frequencies for the linked di- or tri-allelic SNPs were listed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. We classified haplotypes into non-protective haplotypes, where when detected, suggested that carriers of the corresponding haplotypes would be at greater MS risk than non-carriers, and protective haplotypes, where when detected, suggested that carriers of the corresponding haplotypes would be at lower MS risk than non-carriers. Studying bi-allelic haplotypes (Table 4) showed that non-protective haplotypes were “Ba,” “ua,” and “Fa” with the ORs 10.55 (95% CI = 1.27–87.46), 5.07 (95% CI = 1.36–18.85), and 3.59 (95% CI = 1.45–8.94), respectively. This means that MS risk was 10.5 times, 5 times, and 3.6 times, respectively, greater for individuals carrying this haplotype compared to non-carriers. Protective haplotypes were “fA” and “ft” where ORs were 0.331 (95% CI = 0.124–0.884) and 0.23 (95% CI = 0.09–0.62), respectively, which means that MS risk was 3 times and 4.3 times lesser for these haplotype carriers compared to non-carriers. Structuring tri-allelic haplotypes (Table 5) showed two protective haplotypes: “fAt” and “BAt” haplotype with ORs 0.2 (95% CI = 0.06–0.66) and 0.43 (95% CI = 0.19–0.97), respectively, with MS risk 5 times and 2.3 times lesser for these haplotype carriers compared to non-carriers. No statistically significant associations were detected for haplotypes compiled as a combination of four or five SNPs (tables not included).

Discussion

Studying VDR gene polymorphisms in association with MS has provoked a large body of research with special interest to the studied race and population. It was concluded from our study that VDR gene variants “f,” “A,” and “t” alleles as well as VDR haplotypes “BAt” and “fAt” may have a protective effect against MS disease in Egyptian population. In our study, females represented most of the studied MS cases which agrees with general MS epidemiology [27, 28] as well as in a recent published survey conducted by Egyptian team on Egyptian MS patients [29]. In the recent years, females outnumbered men with MS which was related to increased levels of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1PR2), a blood vessel receptor protein that is expressed at higher levels by female brain tissue and controls the immune cells passage across brain blood vessels causing the inflammation that promotes MS [30].

In the present study, we analyzed VDR gene SNPs, FokI in the 5′ promoter area and BsmI, ApaI, TaqI, and Tru9I in the 3′UTR (three prime untranslated region), and their relation to MS in Egyptian patients for a better understanding of MS susceptibility. According to our data, statistically significant higher percent of FokI genotype (Ff+ff) was detected in the healthy controls compared to MS cases with statistically significant association of “f” allele with the control group indicating the possible association of “f” allele with decreased MS risk.

Our result is in accordance with other studies that demonstrated the association between “ff” genotype with reduced MS risk suggesting a role for FokI SNP in MS pathogenesis [3, 15]. Mamutse et al. reported an association between ff genotype and less MS disability outcome in patients diagnosed with MS for over 10 years [15]. However, Bettencourt et al.’s study detected ff genotype more in MS patients with no difference in disease course or disability progression, even though they could not rule out FokI role in MS [19]. Simon et al. showed no significant association between genotypes of FokI and MS disease [31]. Nevertheless, they observed an interaction between dietary intake of vitamin D and FokI polymorphism on MS risk, where the protective effect of increasing vitamin D supplement was apparent in women with the “ff” genotype with significant 80% reduced risk of MS [31]. They explained their findings in the context of variation in VDR protein functionality resulted from FokI polymorphism effect, where among women with increased target cell activity, any slight exposure to vitamin D might be enough to maintain a healthy immunologic environment. Meanwhile, there were studies that could not detect any association between FokI and MS diseases [18, 20]. The study conducted by Smolders et al. showed an association between “F” allele and low 25(OH) D in patients and controls which highlighted FokI role in vitamin D metabolism in MS [18].

Changes in VDR protein sequence result in major functional impacts, as changes in DNA binding, transcriptional activation or heterodimerization, and hormonal ligand affinity [13, 32]. FokI SNP results in frameshift mutations and introduces premature methionine start codon which creates shorter/wild/F-VDR or a long/f-VDR proteins resulting in different VDR protein structure and function [13]. The short “F” isoform has been associated with a higher transcriptional activity and more efficient protein interaction [13, 33, 34]. van Etten et al. showed that VDR FokI polymorphism affected immune cell behavior as monocytes, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes with a more active immune system for the short F-VDR, highlighting its role in immune-mediated diseases [35, 36].

We expanded our study and included 3′UTR region VDR polymorphisms BsmI, ApaI, TaqI, and Tru9I and studied their frequencies and association with MS. 3′UTR regulatory region affects mRNA stability and translational activity, which is important in understanding the functionality of sequence variations in the 3′UTR [37]. Our study showed statistically significant higher percent of ApaI genotype (Aa+aa) in MS compared to controls with statistically significant association of “a” allele with MS cases than with control group. For TaqI, although no statistically significant difference was detected between TaqI genotype in MS cases and controls, TaqI allelic distribution showed a statistically significant association of “t” allele with control group than with MS cases. No statistically significant differences were detected between MS cases or controls with respect to BsmI and Tru9I genotype or allelic distribution. Most of the published work agreed with part of our data and disagreed with others, keeping in mind these variations mainly correlated to the studied population. The study published by Cierny et al. on Slovaks showed an association between BsmI and MS risk, yet no association between ApaI or TaqI and MS was detected [7]. Another study conducted by a Turkish group concluded an association between FokI and MS, yet no association was detected between TaqI or ApaI and MS risk [22]. Studying the Greek population, being epidemiologically comparable to the Middle East and North Africa where Egypt belongs, showed no association between BsmI and MS [38]. The effect of allele variation between populations can be attributed to differences in environmental factors affecting these populations, e.g., exposure to ultraviolet irradiation and diet [12]. This may explain the significant association between some VDR polymorphisms and MS in certain populations, e.g., BsmI and ApaI polymorphisms in Japanese population [39], TaqI and ApaI polymorphisms in Australian population [20], and FokI, ApaI, and TaqI in Egyptian population according to our study.

Following the study of VDR polymorphisms, we thought it is important to understand how they relate to each other. Polymorphisms can be related genetically where the alleles are linked to each other and can be studied by linkage disequilibrium (LD), or biologically (functionally) and studied by analyzing alleles interaction that can enhance or reduce gene functional effects. Additionally, analyzing multiple polymorphisms and haplotypes may help to understand contradictory results from other studies.

In controls, our study demonstrated a statistically significant LD between FokI and both ApaI and TaqI, with nearly comparable D' strength. FokI is often considered an independent marker in the VDR gene showing no LD with any of the other VDR SNPs [40, 41]; however, Sweeney et al.’s study on colorectal cancer showed LD between FokI-BsmI and FokI-Poly (A) polymorphisms in Asians [42].

In the current study, haplotype structure analysis revealed that both BAt and fAt haplotypes were associated with controls more than MS cases, which means that MS risk was 2.3 and 5 times lesser, respectively, for individuals carrying any of these haplotypes compared with non-carrier. The identified haplotypes matched our detected LD and were distributed sensibly between the study group. Bsm-Apa-Taq haplotype can be considered the commonest studied haplotype in respect to VDR function [42,43,44]. Researches who studied bone mineral density demonstrated that BAt haplotype expressed better response than baT haplotype in improving bone mineral density in response to several treatments [42,43,44]. This was explained in terms of better mRNA stability and half-life, which would hypothetically result in higher quantities of VDR protein being translated in the target cells with preferred response to vitamin D effect. Thakkinstian et al. pointed in their study that baT was the most common haplotype for the VDR gene, regardless of ethnicity, followed by BAt and bAT in Caucasians, and bAT and BaT in Asians [43]. We identified BAt and fAt haplotypes as protective haplotypes from MS in Egyptians. Studying the four SNPs haplotype together, FokI, BsmI, ApaI, and TaqI showed that there was a trend of increased frequency of “fBAt” haplotype in controls than in MS cases, suggesting that this haplotype could be a protective haplotype, and on a bigger scale study, more definitive results can be concluded. Similar study investigated FokI, BsmI, ApaI, and TaqI haplotype in Korean population and found no significant association for BsmI and TaqI but observed that the haplotype “fbaT” was associated with a reduced colorectal cancer risk [45].

Conclusion

A corollary of this work is that studying several VDR gene polymorphic site variations is imperative to comprehend VDR functionality and increase the likelihood for distinguishing alleles contributing to common diseases risk. LD pattern and degree at each genomic region contrasted broadly, and the discrepancy seen between populations strengthens the requirement for characterizing haplotypes and LD of studied population. Establishing registries in Egypt to study the clinical course of the MS disease, safety and benefit of including vitamin D supplements in treatment protocols, and the epidemiology of MS in Egypt are highly recommended [29]. Further investigation is needed with the inclusion of more cases to avoid results that can be inflated by small samples or low frequencies of minor alleles.

Availability of data and materials

The data used or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

Abbreviations

- 3′UTR:

-

Three prime untranslated region

- bp:

-

Base pair

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- D′:

-

Linkage disequilibrium coefficient D′

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- OR:

-

Odds ratios

- PPMS:

-

Primary progressive MS

- PRMS:

-

Progressive relapsing MS

- RFLP:

-

Restriction fragment length polymorphism

- RPMS:

-

Relapsing/remitting MS

- S1PR2:

-

Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2

- SCP:

-

Start codon polymorphism

- SNPs:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- SPMS:

-

Secondary progressive MS

- VD:

-

Vitamin D

- VDR:

-

Vitamin D receptor

References

Khosravi-Largani M, Pourvali-Talatappeh P, Rousta AM, Karimi-Kivi M, Noroozi E, Mahjoob A et al (2018) A review on potential roles of vitamins in incidence, progression, and improvement of multiple sclerosis. eNeurologicalSci. 10:37–44

Disanto G, Morahan JM, Ramagopalan SV (2012) Multiple sclerosis: risk factors and their interactions. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 11:545–555

Partridge JM, Weatherby SJ, Woolmore JA, Highland DJ, Fryer AA, Mann CL et al (2004) Susceptibility and outcome in MS: associations with polymorphisms in pigmentation-related genes. Neurology. 62:2323–2325

Ramagopalan SV, Dobson R, Meier UC, Giovannoni G (2010) Multiple sclerosis: risk factors, prodromes, and potential causal pathways. Lancet Neurol. 9:727–739

Behrens JR, Rasche L, Giess RM, Pfuhl C, Wakonig K, Freitag E et al (2016) Low 25-hydroxyvitamin D, but not the bioavailable fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D, is a risk factor for multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 23:62–67

Chen XL, Zhang ML, Zhu L, Peng ML, Liu FZ, Zhang GX et al (2017) Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and the risk of multiple sclerosis: an updated meta-analysis. Microb Pathog. 110:594–602

Cierny D, Michalik J, Skerenova M, Kantorova E, Sivak S, Javor J et al (2016) ApaI, BsmI and TaqI VDR gene polymorphisms in association with multiple sclerosis in Slovaks. Neurol Res. 38:678–684

Abdollahzadeh R, Fard MS, Rahmani F, Moloudi K, Kalani BS, Azarnezhad A (2016) Predisposing role of vitamin D receptor (VDR) polymorphisms in the development of multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. J Neurol Sci. 367:148–151

Ascherio A, Munger KL, Simon KC (2010) Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 9:599–612

Mark BL, Carson JA (2006) Vitamin D and autoimmune disease--implications for practice from the multiple sclerosis literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 106:418–424

Smolders J, Damoiseaux J, Menheere P, Hupperts R (2008) Vitamin D as an immune modulator in multiple sclerosis, a review. J Neuroimmunol. 194:7–17

Uitterlinden AG, Fang Y, Van Meurs JB, Pols HA, Van Leeuwen JP (2004) Genetics and biology of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms. Gene. 338:143–156

Arai H, Miyamoto K, Taketani Y, Yamamoto H, Iemori Y, Morita K et al (1997) A vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism in the translation initiation codon: effect on protein activity and relation to bone mineral density in Japanese women. J Bone Miner Res. 12:915–921

Smolders J, Peelen E, Thewissen M, Menheere P, Tervaert JW, Hupperts R et al (2009) The relevance of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms for vitamin D research in multiple sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 8:621–626

Mamutse G, Woolmore J, Pye E, Partridge J, Boggild M, Young C et al (2008) Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism is associated with reduced disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 14:1280–1283

Morrison NA, Yeoman R, Kelly PJ, Eisman JA (1992) Contribution of trans-acting factor alleles to normal physiological variability: vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and circulating osteocalcin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 89:6665–6669

Faraco JH, Morrison NA, Baker A, Shine J, Frossard PM (1989) ApaI dimorphism at the human vitamin D receptor gene locus. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:2150

Smolders J, Damoiseaux J, Menheere P, Tervaert JW, Hupperts R (2009) Fok-I vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism (rs10735810) and vitamin D metabolism in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 207:117–121

Bettencourt A, Boleixa D, Guimaraes AL, Leal B, Carvalho C, Bras S et al (2017) The vitamin D receptor gene FokI polymorphism and multiple sclerosis in a Northern Portuguese population. J Neuroimmunol. 309:34–37

Tajouri L, Ovcaric M, Curtain R, Johnson MP, Griffiths LR, Csurhes P et al (2005) Variation in the vitamin D receptor gene is associated with multiple sclerosis in an Australian population. J Neurogenet. 19:25–38

Monticielo OA, Brenol JC, Chies JA, Longo MG, Rucatti GG, Scalco R et al (2012) The role of BsmI and FokI vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in Brazilian patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 21:43–52

Kamisli O, Acar C, Sozen M, Tecellioglu M, Yucel FE, Vaizoglu D et al (2018) The association between vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and multiple sclerosis in a Turkish population. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 20:78–81

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M et al (2011) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 69:292–302

Flugge J, Krusekopf S, Goldammer M, Osswald E, Terhalle W, Malzahn U et al (2007) Vitamin D receptor haplotypes protect against development of colorectal cancer. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 63:997–1005

Lewontin RC (1964) The interaction of selection and linkage. I. General considerations; Heterotic Models. Genetics. 49:49–67

Ching A, Caldwell KS, Jung M, Dolan M, Smith OS, Tingey S et al (2002) SNP frequency, haplotype structure and linkage disequilibrium in elite maize inbred lines. BMC Genet. 3:19

Koch-Henriksen N, Sorensen PS (2010) The changing demographic pattern of multiple sclerosis epidemiology. Lancet Neurol. 9:520–532

Magyari M (2016) Gender differences in multiple sclerosis epidemiology and treatment response. Dan Med J. 63(3):pii: B5212

Zakaria M, Zamzam DA, Abdel Hafeez MA, Swelam MS, Khater SS, Fahmy MF et al (2016) Clinical characteristics of patients with multiple sclerosis enrolled in a new registry in Egypt. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 10:30–35

Cruz-Orengo L, Daniels BP, Dorsey D, Basak SA, Grajales-Reyes JG, McCandless EE et al (2014) Enhanced sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 expression underlies female CNS autoimmunity susceptibility. J Clin Invest. 124:2571–2584

Simon KC, Munger KL, Xing Y, Ascherio A (2010) Polymorphisms in vitamin D metabolism related genes and risk of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 16:133–138

Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Haussler CA, Hsieh JC, Thompson PD, Selznick SH et al (1998) The nuclear vitamin D receptor: biological and molecular regulatory properties revealed. J Bone Miner Res. 13:325–349

Jurutka PW, Remus LS, Whitfield GK, Thompson PD, Hsieh JC, Zitzer H et al (2000) The polymorphic N terminus in human vitamin D receptor isoforms influences transcriptional activity by modulating interaction with transcription factor IIB. Mol Endocrinol. 14:401–420

Colin EM, Weel AE, Uitterlinden AG, Buurman CJ, Birkenhager JC, Pols HA et al (2000) Consequences of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms for growth inhibition of cultured human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 52:211–216

van Etten E, Verlinden L, Giulietti A, Ramos-Lopez E, Branisteanu DD, Ferreira GB et al (2007) The vitamin D receptor gene FokI polymorphism: functional impact on the immune system. Eur J Immunol. 37:395–405

Gross C, Krishnan AV, Malloy PJ, Eccleshall TR, Zhao XY, Feldman D (1998) The vitamin D receptor gene start codon polymorphism: a functional analysis of FokI variants. J Bone Miner Res. 13:1691–1699

Kuersten S, Goodwin EB (2003) The power of the 3' UTR: translational control and development. Nat Rev Genet. 4:626–637

Sioka C, Papakonstantinou S, Markoula S, Gkartziou F, Georgiou A, Georgiou I et al (2011) Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in multiple sclerosis patients in northwest Greece. J Negat Results Biomed. 10(3)

Fukazawa T, Yabe I, Kikuchi S, Sasaki H, Hamada T, Miyasaka K et al (1999) Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism with multiple sclerosis in Japanese. J Neurol Sci. 166:47–52

Fang Y, van Meurs JB, d'Alesio A, Jhamai M, Zhao H, Rivadeneira F et al (2005) Promoter and 3'-untranslated-region haplotypes in the vitamin d receptor gene predispose to osteoporotic fracture: the rotterdam study. Am J Hum Genet. 77:807–823

Nejentsev S, Godfrey L, Snook H, Rance H, Nutland S, Walker NM et al (2004) Comparative high-resolution analysis of linkage disequilibrium and tag single nucleotide polymorphisms between populations in the vitamin D receptor gene. Hum Mol Genet. 13:1633–1639

Sweeney C, Curtin K, Murtaugh MA, Caan BJ, Potter JD, Slattery ML (2006) Haplotype analysis of common vitamin D receptor variants and colon and rectal cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 15:744–749

Thakkinstian A, D’Este C, Attia J (2004) Haplotype analysis of VDR gene polymorphisms: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 15:729–734

Bell NH, Morrison NA, Nguyen TV, Eisman J, Hollis BW (2001) ApaI polymorphisms of the vitamin D receptor predict bone density of the lumbar spine and not racial difference in bone density in young men. J Lab Clin Med. 137:133–140

Park K, Woo M, Nam J, Kim JC (2006) Start codon polymorphisms in the vitamin D receptor and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Lett. 237:199–206

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH conceived of the study and revised the manuscript draft. AD participated in conceiving the study and supervised the selection of MS cases and controls. DE supervised the molecular genetic studies and the statistical analysis and interpretation, and helped in drafting the manuscript. IT carried out the molecular genetic work and the statistical study and interpretation, and helped in drafting the manuscript. AF participated in the design and coordination of the study and the statistical analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and accepted the publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been carried out following the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, in accordance with Helsinki Declaration (reference serial number: 0101952). Informed written consent to participate in the study was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassab, A.H., Deif, A.H., Elneely, D.A. et al. Protective association of VDR gene polymorphisms and haplotypes with multiple sclerosis patients in Egyptian population. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 20, 4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-019-0009-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43042-019-0009-2