Abstract

Background

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess whether ventricular longitudinal strain can be used as a prognostication tool in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

Systematic literature searches of PubMed, Embase, and EuropePMC databases were performed on 16 November 2020. Left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LV-GLS) refers to LV contraction measurement using the speckle tracking-based method refers to the mean of strain values of the RV free wall (three segments) measured using echocardiography. The main outcome was poor outcome, defined as a composite of mortality and severe COVID-19.

Results

Seven studies comprising of 612 patients were included in meta-analysis. Six studies have mortality as their outcome, and 1 study has severity as their outcome. Patients with poor outcome have lower LV-GLS (SMD 1.15 (0.57, 1.72), p < 0.001; I2 70.4%). Each 1% decrease in LV-GLS was associated with 1.4x increased risk of poor outcome (OR 1.37 (1.12, 1.67), p = 0.002; I2 48.8%). Patients with poor outcome have lower RV-LS (SMD 1.18 (0.91, 1.45), p < 0.001; I2 0%). Each 1% decrease in RV-LS was associated with 1.3x increased risk of poor outcome (OR 1.25 (1.15, 1.35), p < 0.001; I2 11.8%). Subgroup analysis showed that for every 1% decrease in LV-GLS and RV-LS is increased mortality with OR of 1.30 (1.12, 1.50) and OR of 1.24 (1.14, 1.35), respectively.

Conclusion

This study shows that lower LV-GLS and RV-LS measurements were associated with poor outcome in patients with COVID-19.

Trial registration

PROSPERO CRD42020221144

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is spreading rapidly and is one of the most common disease today [1]. Although most of COVID-19 infections are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, a proportion of patients, especially those with comorbidities https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104324, are at higher risk for severe illness. Severe illness may lead to cardiac injury, multiple organ failure, and death [2, 3].

Since cardiac injury is frequently encountered in patients with COVID-19, routine echocardiography in selected patients is reasonable. Bedside echocardiography is time and cost-efficient. Routine echocardiography is also useful in critical care settings. Global longitudinal strain (GLS) measurement provides direct measurement of myocardial deformation; thus, it is less affected by different loading conditions compared to ejection fraction [4]. Ventricular strain has been shown to be a useful tool for prognostication in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [5]. Studies indicate the potential use of ventricular strain assessment for prognostication in patients with COVID-19 [6,7,8].

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to assess whether ventricular longitudinal strain can be used as a prognostication tool in patients with COVID-19. Ventricular longitudinal strain comprises of left ventricular GLS (LV-GLS) and right ventricular free wall longitudinal strain (RV-LS), measured using speckle tracking echocardiography.

Methods

This study is in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines (Fig. 1). The protocol for this study is registered in the PROSPERO [9] (CRD42020221144).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were all studies with primary data reporting patients with COVID-19 along with the data on the LV-GLS or RV-LS for prognostic purposes. The main outcome was poor outcome, defined as a composite of mortality and severe COVID-19. Mortality was defined as clinically validated death/mortality/non-survivor. Severe COVID-19 was defined as COVID-19 that fulfills the criteria for severe CAP, including the need for mechanical ventilation [10].

The exclusion criteria were preprints, review articles, non-research letters, commentaries, case reports, and articles in non-English Language. Preprints were excluded due to inconsistent credibility [11].

Search strategy and study selection

Systematic literature searches of PubMed, Embase, and EuropePMC databases were performed with keywords “SARS-CoV-2” OR “COVID-19” OR “2019-nCoV” AND “longitudinal strain” on 16 November 2020. The PubMed (MEDLINE) search strategy was ((SARS-CoV-2) OR (COVID-19) OR (2019-nCoV)) AND (longitudinal strain)). Duplicates were removed, and two authors independently screened the articles’ title/abstract. Potentially relevant articles were then assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Two independent authors extracted the data from eligible studies with the help of standardized extraction form that comprises of first author, year of publication, study design, age, male (gender), hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic lung disease (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma), the outcome of interest, and its effect estimates.

LV-GLS refers to the measurement of LV contraction using the speckle tracking-based method [12, 13]. RV-LS refers to the mean of strain values of the RV free wall (three segments) measured using echocardiography [14].

The main outcome was poor outcome; the effect estimate was reported in odds ratio (OR) which is pooled from the adjusted effect estimate extracted from the corresponding studies. Standardized mean difference (SMD) of the LV-GLS and RV-LS between patients with poor outcome and favorable outcome was obtained.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to facilitate quality assessment of the included studies which was performed by two independent authors. Discrepancies that arise at the end of assessment were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

To perform meta-analysis of the extracted data, we use STATA 16 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA). Effect estimate comprising of continuous variables were reported as SMD along with its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The adjusted ORs were pooled using the DerSimonian & Laird random-effects model, irrespective of heterogeneity, and reported as ORs along with its 95% CI. The p values of the effect estimates were two-tailed, and statistical significance was set at ≤ 0.05. To assess inter-study heterogeneity, we performed I squared (I2) and Cochrane Q test; a value of > 50% or p value < 0.10 indicates the presence of heterogeneity. Inverted funnel plot analysis was generated to help evaluate the presence of publication bias qualitatively. Regression-based Egger’s test was conducted to assess the presence of small-study effects. We performed a subgroup analysis to assess the association between LV-GLS, RV-GLS, and mortality.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Initial search yields 410 records, and 377 remained after removal of duplicates. The articles were then screened for title/abstract, and 367 records were excluded. Ten potentially eligible articles were evaluated based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Three full-text articles were excluded because (1) comparison was between cardiac vs non-cardiac injury (n = 1); (2) comparison was between COVID-19 (+) vs COVID-19 (-) (n = 1); and (3) case series with inadequate comparison (n = 1). There were seven studies comprising of 612 patients in the qualitative and quantitative synthesis [4, 6,7,8, 15,16,17]. The baseline characteristics of the included studies are displayed in Table 1. Six studies have mortality as their outcome, and 1 study has severity as their outcome. The result of quality assessment using NOS can be seen in Table 1.

LV-GLS and poor outcome

Patients with poor outcome have lower LV-GLS (SMD 1.15 (0.57, 1.72), p < 0.001; I2 70.4%, p = 0.018) (Fig. 2a). Each 1% decrease in LV-GLS was associated with 1.4x increased risk of poor outcome (OR 1.37 (1.12, 1.67), p = 0.002; I2 48.8%, p = 0.119) (Fig. 2b).

Subgroup analysis for mortality indicated that LV-GLS (SMD 0.96 (0.32, 1.60), p < 0.001; I2 71.7%, p = 0.029) was lower in non-survivors. Each 1% decrease in LV-GLS was associated with 1.3x increased mortality (OR 1.30 (1.12, 1.50), p = 0.001; I2 30.8%, p = 0.236).

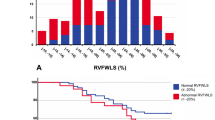

RV-LS and poor outcome

Patients with poor outcome have lower RV-LS (SMD 1.18 (0.91, 1.45), p < 0.001; I2 0%, p = 0.751) (Fig. 3a). Each 1% decrease in RV-LS was associated with 1.3x increased risk of poor outcome (OR 1.25 (1.15, 1.35), p < 0.001; I2 11.8%, p = 0.338) (Fig. 3b).

Subgroup analysis for mortality indicated that RV-LS (SMD 1.18 (0.89, 1.48), p < 0.001; I2 0%, p = 0.549) was lower in non-survivors. Each 1% decrease in RV-LS was associated with 1.2x increased mortality (OR 1.24 (1.14, 1.35), p < 0.001; I2 15.8%, p = 0.313).

Risk of publication bias

The mean difference in terms of LV-GLS in patients with poor outcome and those without having a symmetrical funnel plot and was non-significant for small-study effects (p = 0.888). However, pooled OR for LV-GLS has an asymmetrical funnel plot and was significant for small-study effects (p = 0.016) (Fig. 4a).

The funnel plot was asymmetrical for the mean difference in terms of RV-LS; however, it was not statistically significant for small-study effects (p = 0.062). The pooled OR for RV-LS also has an asymmetrical funnel plot (Fig. 4b) but a not statistically significant for small-study effects (p = 0.099).

Discussion

This meta-analysis indicates that lower LV-GLS and RV-LS were independently associated with poor outcome in COVID-19. Subgroup analysis indicate that for every 1% decrease in LV-GLS and RV-LS, the mortality increased for 1.3x and 1.24x, respectively.

Systemic inflammation induced by COVID-19 may culminate in LV and RV failure [2, 18,19,20,21]. Patients with COVID-19 often have reduced basal LV strain, especially in those with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension [22]. The latter comorbidities affect the subendocardial fibers, inducing LV fibrotic process [23, 24]. Lassen et al. also reported lower LV-GLS and RV-LS in patients with COVID-19 compared to those without [4]. Cardiac injury is frequently observed in patients with COVID-19 and is associated with increased mortality [3]. Myocardial injury is expected to affect GLS and GLS has been shown to be a predictor of heart failure in patients with myocardial infarction [25]. However, a study showed that elevated troponin was not associated with LV-GLS in patients with COVID-19, despite an increase in adverse events [26]. A smaller study showed that there was no significant difference in terms of LV-GLS between those without COVID-19, with COVID-19, and COVID-19 + increased cardiac troponin [27]. Thus, reduced GLS might also be affected by acute conditions such as myopericardial damage and acute respiratory distress syndrome to other chronic causes (comorbidities) such as cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and diabetes. A study noted that pericardial involvement was associated with lower GLS, in patients with COVID-19 [28]. Reduced GLS might be associated with the severity of myopericardial damages, suggesting that regional longitudinal strain is an important marker, even in asymptomatic COVID-19 patients [28]. Croft et al. study showed that there was no significant difference in terms of LV-GLS in non-survivors compared to survivors, this is likely due to the high prevalence of hypertension in the patients. As previously discussed, hypertension is expected to reduce the LV-GLS [22,23,24]; thus, difference will be marginal at best. Croft et al. sample size was small, amidst the high prevalence of hypertension; a larger sample size might be needed to demonstrate significant difference. Comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and drugs related to them affect COVID-19-related mortality; thus, these variables may confound the analysis, primarily if they are unequally distributed in the two groups [29,30,31,32,33]. GLS has been shown to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes without prior cardiovascular diseases; which thought to be caused by subclinical myocardial systolic dysfunction, reduced GLS was observable even in normotensive and asymptomatic patients [34,35,36]. Abdominal obesity has also been associated with reduced GLS [37]. Hence, these factors may affect the pooled effect estimate.

The right ventricular strain has previously been shown to be useful for prognostication of patients with ARDS [5, 38]. Inflammation is thought to cause RV overload and damage that resulted in RV failure, which can be assessed by RV-LS [17]. Free wall has a more excellent prognostic value than total RV strain in patients with COVID-19 [16]. One of RV-LS’s advantage is that the performance of RV-LS as a prognostication tool is independent of LV systolic functional index [8]. The included studies uniformly reported that RV-LS was associated with poor outcome with low heterogeneity (11.8%).

Baycan et al. reported that LV-GLS > − 15.2% has an OR of 8.34, area under a curve (AUC) 0.83, sensitivity of 77%, and specificity of 75%, while RV-LS > − 18.45% has an OR of 6.23, AUC 0.77, sensitivity of 72%, and specificity of 66% [16]. Li et al. found that RV-LS at − 23% cutoff was associated with AUC 0.87, sensitivity of 94.4%, and specificity of 64.7% [8]. Croft et al. reported that LV-GLS reduction of > 8.5 showed trend towards increased mortality, but was not independently associated; the unadjusted or adjusted ratio and their corresponding p values were not thoroughly reported [6].

Clinical implications

LV-GLS and RV-GLS are potentially useful in assessing patients with COVID-19. Lower longitudinal strain has been shown to be independently associated with poor outcome. Additionally, cardiac injury is not uncommon and markedly increased the mortality. Hence, routine echocardiography is reasonable and might be useful in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Considering the time and resources taken to perform echocardiography, the decision should account for individual regions’ capability. In a region with limited resources, routine echocardiography can be performed in COVID-19 with moderate severity or patients at high risk; while the region with greater resources, echocardiography can be performed more liberally. A robust risk prediction model can be made by combining cardiac troponin, natriuretic peptides https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-137884, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic findings.

Limitations

Most of the included studies were retrospective in design, which is a potential source of bias. The data presented by the studies were inadequate to facilitate diagnostic meta-analysis which might be useful in determining post-test probability of patients with high or low GLS. If reported, the cutoff points of LV-GLS and RV-LS were highly polarized. The comorbidities such as hypertension and obesity may affect the analysis; since the number of available studies was small, we cannot perform meta-regression analysis.

Conclusion

This study shows that lower LV-GLS and RV-LS measurements were associated with poor outcome in patients with COVID-19.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AUC:

-

Area under a curve

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- GLS:

-

Global longitudinal strain

- LV-GLS:

-

Left ventricular global longitudinal strain

- NOS:

-

Newcastle Ottawa Scale

- RV-LS:

-

Right ventricular longitudinal strain

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

References

World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 95. World Heal. Organ. 2020.

Lim MA, Pranata R, Huang I, Yonas E, Soeroto AY, Supriyadi R. Multiorgan failure with emphasis on acute kidney injury and severity of COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Kidney Heal Dis. 2020;7.

Santoso A, Pranata R, Wibowo A, Al-Farabi MJ, Huang I, Antariksa B. Cardiac injury is associated with mortality and critically ill pneumonia in COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020.

Lassen MCH, Skaarup KG, Lind JN, Alhakak AS, Sengeløv M, Nielsen AB, et al. Echocardiographic abnormalities and predictors of mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: the ECHOVID-19 study. ESC Hear Fail. 2020:1–9.

Lemarié J, Maigrat C-H, Kimmoun A, Dumont N, Bollaert P-E, Selton-Suty C, et al. Feasibility, reproducibility and diagnostic usefulness of right ventricular strain by 2-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography in ARDS patients: the ARD strain study. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:24.

Croft LB, Krishnamoorthy P, Ro R, Anastasius M, Zhao W, Buckley S, et al. Abnormal left ventricular global longitudinal strain by speckle tracking echocardiography in COVID-19 patients. Future Cardiol. 2020.

Janus SE, Hajjari J, Karnib M, Tashtish N, Al-Kindi SG, Hoit BD. Prognostic value of left ventricular global longitudinal strain in COVID-19. Am J Cardiol. 2020;131:134–6.

Li Y, Li H, Zhu S, Xie Y, Wang B, He L, et al. Prognostic value of right ventricular longitudinal strain in patients with COVID-19. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2287–99.

Pranata R, Wibowo A, Astuti A, Tiksnadi B, Martanto E, Martha J, Purnomowati A, Akbar M. Prognostic value of the left and right ventricular longitudinal strain in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PROSPERO 2020 CRD42020221144. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020221144.

Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–67.

Henrina J, Lim MA, Pranata R. COVID-19 and misinformation: how an infodemic fuelled the prominence of vitamin D. Br J Nutr. 2020:1–2.

Leitman M, Lysyansky P, Sidenko S, Shir V, Peleg E, Binenbaum M, et al. Two-dimensional strain-a novel software for real-time quantitative echocardiographic assessment of myocardial function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:1021–9.

Reisner SA, Lysyansky P, Agmon Y, Mutlak D, Lessick J, Friedman Z. Global longitudinal strain: a novel index of left ventricular systolic function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:630–3.

Mor-Avi V, Lang RM, Badano LP, Belohlavek M, Cardim NM, Derumeaux G, et al. Current and evolving echocardiographic techniques for the quantitative evaluation of cardiac mechanics: ASE/EAE consensus statement on methodology and indications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:277–313.

Kim M, Nam JH, Son JW, Kim SO, Son NH, Ahn CM, et al. Cardiac manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a multicenter cohort study. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e366.

Baycan OF, Barman HA, Atici A, Tatlisu A, Bolen F, Ergen P, et al. Evaluation of biventricular function in patients with COVID-19 using speckle tracking echocardiography. Springer Netherlands: Int J Cardiovasc Imaging; 2020.

Bursi F, Santangelo G, Sansalone D, Valli F, Vella AM, Toriello F, et al. Prognostic utility of quantitative offline 2D-echocardiography in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 disease. Echocardiography. 2020:1–11.

Argulian E, Sud K, Vogel B, Bohra C, Garg VP, Talebi S, et al. Right ventricular dilation in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 infection. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:2459–61.

Xiong TY, Redwood S, Prendergast B, Chen M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1798–800.

Huang I, Pranata R, Lim MA, Oehadian A, Alisjahbana B. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, D-dimer, and ferritin in severe coronavirus disease-2019: a meta-analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2020;14:175346662093717.

Yonas E, Alwi I, Pranata R, Huang I, Lim MA, Gutierrez EJ, et al. Effect of heart failure on the outcome of COVID-19 — a meta analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2020.

Goerlich E, Gilotra NA, Minhas AS, Bavaro N, Hays AG, Cingolani OH. Prominent longitudinal strain reduction of basal left ventricular segments in patients with COVID-19. J Card Fail. 2020.

Chan J, Hanekom L, Wong C, Leano R, Cho GY, Marwick TH. Differentiation of subendocardial and transmural infarction using two-dimensional strain rate imaging to assess short-axis and long-axis myocardial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2026–33.

Kang SJ, Lim HS, Choi BJ, Choi SY, Hwang GS, Yoon MH, et al. Longitudinal strain and torsion assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking correlate with the serum level of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1, a marker of myocardial fibrosis, in patients with hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:907–11.

Lee SH, Lee S-R, Rhee K-S, Chae J-K, Kim W-H. Usefulness of myocardial longitudinal strain in prediction of heart failure in patients with successfully reperfused anterior wall ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2019;49:960.

Balaban Kocas B, Cetinkal G, Ser OS, Kilci H, Keskin K, Ozcan SN, et al. The relation between left ventricular global longitudinal strain and troponin levels in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging [Internet]. 2020; Available from: http://link.springer.com/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10554-020-02102-1.

Lairez O, Blanchard V, Houard V, Vardon-Bounes F, Lemasle M, Cariou E, et al. Cardiac imaging phenotype in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): results of the cocarde study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020.

Brito D, Meester S, Yanamala N, Patel HB, Balcik BJ, Casaclang-Verzosa G, et al. High prevalence of pericardial involvement in college student athletes recovering from COVID-19. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging [Internet]. 2020; Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1936878X20309463.

Pranata R, Huang I, Lim MA, Wahjoepramono EJ, July J. Impact of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases on mortality and severity of COVID-19–systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29.

Pranata R, Lim MA, Huang I, Raharjo SB, Lukito AA. Hypertension is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2020;21:147032032092689.

Pranata R, Permana H, Huang I, Lim MA, Soetedjo NNM, Supriyadi R, et al. The use of renin angiotensin system inhibitor on mortality in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. Elsevier Ltd. 2020;14:983–90.

Pranata R, Lim MA, Yonas E, Vania R, Lukito AA, Siswanto BB, et al. Body mass index and outcome in patients with COVID-19: a dose-response meta-analysis. Elsevier Masson SAS: Diabetes Metab; 2020.

Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia – a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression: Diabetes and COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14.

Holland DJ, Marwick TH, Haluska BA, Leano R, Hordern MD, Hare JL, et al. Subclinical LV dysfunction and 10-year outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Heart. 2015;101:1061–6.

Ng ACT, Delgado V, Bertini M, van der Meer RW, Rijzewijk LJ, Shanks M, et al. Findings from left ventricular strain and strain rate imaging in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1398–401.

Liu JH, Chen Y, Yuen M, Zhen Z, Chan CWS, Lam KSL, et al. Incremental prognostic value of global longitudinal strain in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15.

Russo C, Sera F, Jin Z, Palmieri V, Homma S, Rundek T, et al. Abdominal adiposity, general obesity, and subclinical systolic dysfunction in the elderly: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Heart Fail [Internet]. 2016;18:537–44. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.521.

Furian T, Aguiar C, Prado K, Ribeiro RVP, Becker L, Martinelli N, et al. Ventricular dysfunction and dilation in severe sepsis and septic shock: relation to endothelial function and mortality. J Crit Care. 2012;27:319.e9-319.e15.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Arief Wibowo: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, writing—original draft, Raymond Pranata: conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, formal analysis, statistical analysis (meta-analysis), investigation, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Astri Astuti: data curation, writing—original draft. Badai Bhatara Tiksnadi: investigation, writing—review and editing. Erwan Martanto: investigation, writing—review and editing. Januar Wibawa Martha: investigation, writing—review and editing. Augustine Purnomowati: investigation, writing—review and editing. Mohammad Rizki Akbar: conceptualization, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

All authors approve the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

None

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wibowo, A., Pranata, R., Astuti, A. et al. Left and right ventricular longitudinal strains are associated with poor outcome in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. j intensive care 9, 9 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-020-00519-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-020-00519-3