Abstract

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the phenotypic and genotypic patterns of aminoglycoside resistance among the Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) isolates collected from pediatric and general hospitals in Iran. A total of 836 clinical isolates of GNB were collected from pediatric and general hospitals from January 2018 to the end of December 2019. The identification of bacterial isolates was performed by conventional biochemical tests. Susceptibility to aminoglycosides was evaluated by the disk diffusion method (DDM). The frequency of genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs) was screened by the PCR method via specific primers. Among all pediatric and general hospitals, the predominant GNB isolates were Acinetobacter spp. (n = 327) and Escherichia coli (n = 144). However, E. coli (n = 20/144; 13.9%) had the highest frequency in clinical samples collected from pediatrics. The DDM results showed that 64.3% of all GNB were resistant to all of the tested aminoglycoside agents. Acinetobacter spp. and Klebsiella pneumoniae with 93.6%, Pseudomonas aeruginosa with 93.4%, and Enterobacter spp. with 86.5% exhibited very high levels of resistance to gentamicin. Amikacin was the most effective antibiotic against E. coli isolates. In total, the results showed that the aac (6')-Ib gene with 59% had the highest frequency among genes encoding AMEs in GNB. The frequency of the surveyed aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes among all GNB was found as follows: aph (3')-VIe (48.7%), aadA15 (38.6%), aph (3')-Ia (31.3%), aph (3')-II (14.4%), and aph (6) (2.6%). The obtained data demonstrated that the phenotypic and genotypic aminoglycoside resistance among GNB was quite high and it is possible that the resistance genes may frequently spread among clinical isolates of GNB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is being increasingly recognized as a serious public health threat worldwide [1,2,3,4]. Antimicrobial resistance is highly noticeable among Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), and therefore, clinical isolates resistant to multiple or almost all available antibiotics have been consistently emerging [5, 6]. The three broad-spectrum classes of antimicrobial agents including β-lactams (especially β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, cephalosporins, and carbapenems), aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones are the most common classes of antibiotics used to treat different infections caused by GNB [1, 7, 8]. Aminoglycosides as broad-spectrum antibiotics have an important role under clinical settings and are used for the treatment of severe and life-threatening hospital-acquired infections caused by GNB [9]. The aminoglycosides including tobramycin, gentamicin, and amikacin play a bactericidal role against a wide range of GNB such as Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), Escherichia coli (E. coli), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) [10, 11]. However, in recent years, resistance to aminoglycosides, especially its association with other antibiotic classes such as β-lactams and fluoroquinolones, has been increasingly reported. Resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics is present virtually all over the world, particularly in Asia and Latin America [12]. The resistance mechanisms against aminoglycosides in GNB mainly result from the (1) production of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes (AMEs), inactivating antibiotics classified in several families such as aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferases (ANTs), aminoglycoside acetyltransferases (AACs), and aminoglycoside phosphoryltransferases (APHs); (2) methylation of 16S rRNA by a family of ribosomal methyltransferase enzymes; (3) mutation in the 30S ribosomal subunit; (4) active expulsion of antibiotics from the bacterial cells by efflux pumps; and (5) alteration of cell membrane permeability and reduction in intracellular concentration of aminoglycosides [13,14,15]. Among these factors, AMEs represent the most common mechanism by which clinical isolates of GNB and Gram-positive bacteria (GPB) can enzymatically modify the hydroxyl or amino groups of the drug, inhibiting their binding to ribosomes and hence allowing the bacteria to survive [16, 17]. According to the several condition such as partial immune system, neonates and children are a susceptible group to bacterial infections. Neonates can acquire bacteria from families or mothers within horizontally and vertically transmission ways, respectively. Antibiotic-resistant GNB can cause severe infections in neonates and children and are considered the main concern for physicians [18].

In Iran, although some authors have reported a high prevalence rate of aminoglycoside resistance among the GNB isolated from clinical samples [19,20,21], the overall prevalence of aminoglycoside-resistant genes among clinical GNB isolates has not been determined widely. Therefore, the present study follows several objectives: (1) evaluation of the phenotypic resistance patterns of GNB; (2) determination of the frequency of common aminoglycoside-resistance genes including genes encoding AMEs; and (3) characterization of the correlation between aminoglycoside-resistance genes and the phenotypic resistance.

Materials and methods

Samples and bacterial isolation

The present study investigated the clinical isolates of GNB that were collected from pediatric and general hospitals throughout Iran during January 2018 to the end of December 2019 (Supplementary file).

Bacterial identification was carried out using conventional biochemical tests including growth on MacConkey (MAC) agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), chocolate agar, and blood agar plates; evaluation of colony morphologies and Gram stain characteristics; oxidase test; catalase test; citrate utilization test; nitrate reduction test; indole production; motility; lactose fermentation; H2S production; urease activity; Methyl Red (MR) test; and Voges Proskauer (VP) test. After identification, all bacterial strains were preserved in Tryptic Soy Broth (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) containing 20% glycerol at – 70 °C for further analysis.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

The susceptibility and resistance patterns of GNB to aminoglycoside agents were determined by the disk diffusion method (DDM) on Mueller Hinton agar medium (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The tested antimicrobial agents included amikacin (30 μg/disk), gentamicin (10 μg/disk), and tobramycin (30 μg/disk). The isolates resistant to at least one of these aminoglycoside agents were considered as aminoglycoside-resistant strain. The results of the DDM method were interpreted based on Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria. E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used as quality control strains in every test run.

Molecular detection of aminoglycoside-resistant genes

Total genomic DNA was extracted from GNB isolates grown in Mueller-Hinton broth (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) overnight at 37 °C. The bacterial cell pellets were resuspended in 250 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then, DNA extraction was performed using High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) in line with the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration of the extracted DNA were evaluated by Nanodrop (DeNovix Inc., USA). Extracted DNA was stored at – 80 °C for further analysis. The frequency of six main genes encoding AMEs including aac (6')-Ib, aph (3')-VIe, aph (3')-II, aadA15, aph (3')-Ia, and aph (6) was screened by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method via specific primers. The sequence of the primers used for performing PCR is shown in Supplementary Table 1. The PCR reaction was performed on a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Mastercycler Gradient; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) under the following condition: 1 cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 56 °C, 57 °C, 60 °C, 63 °C, and 64 °C according to the specific temperature for each primer for 35–40 s, and then extension step at 72 °C for 1 min followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR products were analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel, stained by DNA-safe stain (SinaClon, Tehran, Iran), and visualized under (UV) light (UVItec, Cambridge, UK).

Statistical analysis

All data regarding the prevalence of isolated bacteria, resistance profile to aminoglycoside agents, and frequency of genes encoding AMEs were added to the statistical package SPSS v.23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and analyzed using descriptive statistical tests.

Results

Distribution of GNB in different clinical samples

From January 2018 to the end of December 2019, 836 GNB were collected from the pediatric and general hospitals in Iran. The hospital origin of all clinical samples is shown in the Supplementary file. In general, 836 different clinical samples were collected from Mofid children’s Hospital in Tehran, Iran. Mofid children’s Hospital is one of the most important educational and research centers in Tehran, the capital of Iran. The frequency of GNB among clinical samples collected from pediatrics was as follows: E. coli (n = 20/144; 13.9%), Acinetobacter spp. (n = 28/327;8.6%), P. aeruginosa (n = 8/136; 5.9%), K. pneumoniae (n = 20/140; 14.3%), and Enterobacter spp. (n = 25/89; 28%).

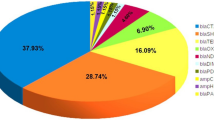

Among all pediatric and general hospitals, the isolated GNB included Acinetobacter spp. (n = 327; 39.1%), E. coli (n = 144; 17.2%), K. pneumoniae (n = 140; 16.5%), P. aeruginosa (n = 136; 16.3%), and Enterobacter spp. (89; 10.6%).

Among GNB, Acinetobacter spp. (n = 186; 56.9%) and P. aeruginosa (n = 55; 40.4%) were isolated frequently from tracheal samples. On the other hand, most isolates of E. coli (n = 119/144; 82.6%) and K. pneumoniae (n = 65/140; 46.4%) were isolated from urine samples. Moreover, Enterobacter spp. (n = 68/89; 76.4%) were isolated frequently from blood samples. The distribution of the isolated bacteria in clinical samples is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

The frequency of GNB by age groups

The frequency of the GNB isolated from pediatric and general hospitals among different age groups is shown in Supplementary Table 3. In general, GNB had the highest and lowest frequency rates among patients in > 50-year and 5- to 14-year age groups, respectively. P. aeruginosa (59%), Acinetobacter spp. (53.7%), and E. coli (43.7%) showed the highest frequency in the age groups > 50 years. The results showed that Acinetobacter spp., P. aeruginosa, and E. coli isolates exhibited the lowest frequency in < 1-year, 1- to 4-year, and 5- to 14-year age groups. On the other hand, K. pneumoniae (27.1%) and Enterobacter spp. (25.8%) revealed the highest frequency in < 1-year age groups. Our analyses revealed that the frequency of K. pneumoniae (6.4%) among patients in the 5- to 14-year age group was low. Moreover, Enterobacter spp. had the lowest frequency in patients belonging to 15- to 29-year age groups.

Antimicrobial susceptibility

Resistance rates of GNB to antimicrobials

The patterns of the resistance of the isolated GNB to aminoglycoside agents used are shown in Table 1. In total, the isolated GNB had the highest and lowest resistance rates to gentamicin (n = 758/836; 90.1%) and amikacin (n = 587/836; 70.2%), respectively. Among GNB, Acinetobacter spp. had the highest level of resistance to aminoglycoside agents and the resistance rates were found as follows: gentamicin (n = 306/327; 93.6%), tobramycin (n = 296/327; 90.5%), and amikacin (n = 295/327/90.2%). E. coli isolates represent the GNB that were significantly susceptible to the tested aminoglycosides with the following resistance rates: gentamicin (n = 117/144; 81.3%), tobramycin (n = 50/144; 34.7%), and amikacin (n = 39/144; 27%). Amikacin was the most effective antibiotic against E. coli isolates. Moreover, results showed that K. pneumoniae (n = 131/140; 93.6%), P. aeruginosa (n = 127/136; 93.4%), and Enterobacter spp. (n = 77/89; 86.5%) had the highest rates of resistance to gentamicin. Moreover, P. aeruginosa isolates had the same rate of resistance (n = 127/136; 93.4%) to tobramycin. In total, our results showed that 64.3% (n = 538/836) GNB including 103 P. aeruginosa, 296 Acinetobacter spp., 19 E. coli, 78 K. pneumoniae, and 42 Enterobacter spp. were resistant to all the three examined aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Frequency of aminoglycoside-resistant genes among GNB

The current study evaluates the distribution of AME genes among phenotypically aminoglycoside-resistant GNB. The distribution of aminoglycoside-resistant genes among GNB is shown in Table 2. Results showed that aac (6')-Ib (n = 492/836; 59%) was the predominant aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme gene. The frequency of surveyed genes encoding AMEs among all GNB is given as follows: aph (3')-VIe (48.7%), aadA15 (38.6%), aph (3')-Ia (31.3%), aph (3')-II (14.4%), and aph (6) (2.6%). The aac (6')-Ib (85.4%) and aph (3')-Ia (74.1%) genes had the highest frequency among the examined genes in Enterobacter spp. isolates. Moreover, the frequency of aph (3')-IIb (68%) and aph (3')-VIe (58%) genes was high in P. aeruginosa isolates. On the other hand, the aadA15 gene (46.5%) was frequently detected among K. pneumoniae isolates. aph (6) gene was only detected in E. coli (11.8%) and Acinetobacter spp. (1.5%). The co-existence of aminoglycoside-resistant genes is shown in Table 3. Our analyses revealed that 8.2% (n = 27/327) of Acinetobacter isolates harbored simultaneously the aac (6')-Ib, aph (3')-Ia, aadA15, and aph (3')-VIe genes. Among E. coli isolates, 0.7% (n = 1/144) of the isolates harbored simultaneously aac (6')-Ib, aph (6), aadA15, aph (3')-II, and aph (3')-Ia genes. The prevalence rates of the co-existence of five aminoglycoside resistance genes including aac (6')-Ib, aph (3')-Ia, aadA15, aph (3')-II, and aph (3')-VIe among K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and Enterobacter isolates were 0.7% (n = 1/140), 5.9% (n = 8/136), and 5.6% (n = 5/89), respectively.

The genotype profiles of bacterial isolates exhibiting resistance to the three detected antibiotics are shown in Table 4. Overall, 59.7% (n = 321/538) and 53.5% (n = 288/538) of all GNB that were resistant to all the three examined antibiotics harbored the aph (3')-VIe and aac (6')-Ib genes, respectively. Results showed that the frequency rates of aac (6')-Ib gene among P. aeruginosa, Enterobacter spp., K. pneumoniae, and E. coli were 95.1%, 71.4%, 69.2%, and 73.7%, respectively. Moreover, 60.8% of Acinetobacter spp. isolates were positive for the aph (3')-VIe gene.

Discussion

In recent years, the incidence of both phenotypic and genotypic aminoglycoside resistance has been surging around the world [22, 23]. The corresponding high resistance rate can severely complicate combination therapy for aminoglycoside agents with broad-spectrum β-lactams including cephalosporins and carbapenems against severe Gram-negative infections, particularly in case of nosocomial infections [24, 25]. Since aminoglycoside agents are the first choice of clinicians for infection treatments [22] and given that aminoglycosides are the most commonly prescribed antimicrobial agents for treating serious GNB in Iran, an attempt is made here to characterize the aminoglycoside resistance by means of phenotypic and genotypic methods among five important GNB isolated from pediatric and general hospitals in Iran. The results of antimicrobial susceptibility screening revealed that about half of the GNB were fully resistant to at least one of the tested aminoglycosides, including gentamicin, tobramycin, and amikacin. Previously, resistance to gentamicin, amikacin, and tobramycin, which are considered as newer aminoglycosides with a broader spectrum of antibacterial activities, was generally found to be less common than resistance to older aminoglycosides such as streptomycin, kanamycin, and neomycin [26].

In the current study, approximately, more than 90% of Acinetobacter spp. exhibited resistance to all the tested aminoglycosides. In a previously published study by Aliakbarzade et al., 103 clinical A. baumannii strains were collected from Imam Reza Hospital of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. They showed that A. baumannii strains were isolated from different clinical samples such as urine, sputum, tracheal secretion, bronchial lavage, wound, and blood. The findings of their study revealed that the rates of resistance to gentamicin, amikacin, and tobramycin were 86%, 81%, and 63%, respectively [27].

Compared to the above studies, we witnessed a significant increase in the number of aminoglycoside-resistant Acinetobacter isolates. In this study, the rate of resistance to gentamicin, amikacin, and tobramycin was 93.6%, 90.2%, and 90.5%, respectively. The high-level resistance to aminoglycoside is a serious issue for combination therapy of aminoglycoside with broad-spectrum β-lactams including carbapenems and cephalosporins against Acinetobacter infections [19]. According to our findings, in comparison to other tested aminoglycoside agents, amikacin caused less resistance in GNB, especially in E. coli isolates, and is still an extremely useful drug in treating severe E. coli infections. Several studies have pointed out that increased resistance against amikacin could be associated with the unrestricted use of this compound by some clinicians [28, 29].

In 2018, Nasiri et al. surveyed the molecular epidemiology of aminoglycoside resistance in clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae. They collected 177 K. pneumoniae strains from the patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) as well as infectious diseases, internal medicine, and surgery wards. K. pneumoniae strains were isolated from different clinical specimens such as urine, wound, sputum, trachea, and blood. The above authors reported that amikacin was a more active antimicrobial agent than other aminoglycosides toward clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae with a resistance rate of 61% [20]. Nevertheless, our findings show that the rate of resistance to amikacin in fact increased to 93.6% among K. pneumoniae isolates, compared to the mentioned studies. Overall, the high frequency of aminoglycoside-resistant GNB suggests that extensive use of these antimicrobial agents in clinical settings of Iran has led to the emergence of resistant isolates.

This study surveyed the prevalence of six main aminoglycoside-resistant genes in GNB. Results showed that a majority of aminoglycoside-resistant GNB (about three-quarters of isolates) harbored at least one AME gene. In total, the aac (6')-Ib (59%) and aph (3')-VIe (48.7%) genes were the most prevalent AME genes among all the aminoglycoside-resistant GNB. Related reports from different parts of the world have illustrated that aac (6´)-II and ant (2´´)-I genes are the most prevalent AME genes in Europe. Moreover, it has been revealed that aph (3′)-VIe, ant (2´´)-I, and aac (6´)-I genes have the highest frequency among AME genes in Korea [11, 30]. On the other hand, aac (6´)-31/aadA15 and aadA2 genes were also detected frequently in the GNB isolated from nosocomial infections in Mexico and Brazil [31, 32]. AMEs are the most important sources of aminoglycoside resistance among bacteria. The corresponding genes are highly mobile and can be transported by integrons, transposons, plasmids, and other transposable gene elements, often along with other resistant genes (such β-lactamases genes). As a matter of fact, the most threatening GNB acquire AME genes through horizontal gene transfer [33, 34].

In total, the aac (6') gene confers resistance to all of the aminoglycosides, except streptomycin. The aph (3′)-VIe was identified in A. baumannii and it conferred resistance to kanamycin, amikacin, neomycin, ribostamycin, paromomycin, butirosin, and isepamycin. The aph (3′)-II gene was described in the P. aeruginosa isolates. The aph (3')-II gene confers resistance to kanamycin, paromomycin, butirosin, neomycin, and ribostamycin. The aadA1 gene remains resistant to streptomycin and spectinomycin. Moreover, the aph (3')-Ia and aph (6) genes correspond to the resistance to kanamycin and tobramycin, respectively [17, 35, 36].

In Iran, a high prevalence rate of AMEs was previously reported in GNBs such as P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, and K. pneumoniae [20, 37, 38]. The aph (3')-VIe was the most common AME in Acinetobacter isolates (52.6%), followed by aadA15 (37.9%), aph (3')-Ia (35.5%), and aac (6')-Ib (34.3%). In a study conducted by Aghazadeh et al. in Iran, aph(3')-VIe and aph(3')-II were the most prevalent AME genes in A. baumannii with prevalence rates of 90.6% and 61.8%, respectively [39]. In another study in Iran, Asadollahi et al. reported that AME genes including aadA12, aacC1, and aadB were the most prevalent ones among A. baumannii [40]. Altogether, these data indicate that aph (3')-VIe and aadA15 genes contribute to aminoglycoside resistance among clinical isolates of A. baumannii in different geographic locations of Iran. Our results were similar to those found by Nasiri et al. in Iran who reported aac(6′) as the most dominant AME among clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae [20]. However, Ghotaslou et al. previously reported that ant(3″)-Ia and aph(3″)-Ib were the most prevalent AME genes in Enterobacteriaceae isolates in the northwest of Iran with frequency rates of 35.9% and 30.5%, respectively [14]. In another research by Soleimani et al., aac (3)-IIa and ant(2″)-Ia genes were identified as the most common AMEs in uropathogenic E. coli isolated from an Iranian hospital [41]. These data suggested that various reasons such as diversity of specimen type, geographic regions, sample size, bacterial sources, usage of antibiotics, and applied detecting methods would affect the distribution patterns of AME. Liang et al. previously reported that aac (3)-II, aac (6′)-Ib, and ant (3″)-I genes were the most common AME genes in K. pneumoniae isolates in China [42]. In Norway, Lindemann et al. indicated that the majority of E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates in their study harbored aac(3)-IIa and aac(6′)-Ib genes [42]. The significant variation of the results may be attributed to geographical factors. Regarding P. aeruginosa isolates, we found aac (6')-Ib and aph (3')-II as the most prevalent AME genes. These findings are consistent with those reported by Aghazadeh et al. in Tabriz, Iran [39]. In general, results demonstrated that more than 90% of GNB were resistant to one of the antibiotics. However, the results of the molecular method revealed that 59% of GNB harbored the aac (6')-Ib gene. Our analyses revealed that 78% of GNB were positive for at least one of the examined genes.

The limitation of this study is that we just sequenced one positive sample of each gene. For sequencing the aac (6')-Ib, aph (3')-II, aph (6), aadA15, and aph (3')-Ia genes, we used a positive sample in E. coli isolates. Moreover, one positive sample among A. baumannii isolates was used for aph (3')-VIe gene sequencing. This limitation was due to the budget limitation. In the analyzed sequences, all taxon affiliation was performed automatically by GenBank in the sequence submission process.

Conclusion

The data obtained in this study indicated that resistance to aminoglycoside in Iran was high and AME genes frequently spread among clinical GNB isolates. Therefore, there are enough reasons to assume that the increasing complexity of aminoglycoside resistance mechanisms is associated with the high complexity of aminoglycoside usage in Iran. However, constant monitoring and surveillance of aminoglycoside resistance, antimicrobials, and consumption can improve the antibiotics prescription regimen and prevent the spread of these resistant bacteria in communities and hospital settings.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- GNB:

-

Gram-negative bacteria

- GPB:

-

Gram-positive bacteria

- AMEs:

-

Aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes

- DDM:

-

Disk diffusion method

- ANTs:

-

Aminoglycoside nucleotidyltransferases

- AACs:

-

Aminoglycoside acetyltransferases

- APHs:

-

Aminoglycoside phosphoryltransferases

- MAC:

-

MacConkey

- MR:

-

Methyl Red

- VP:

-

Voges Proskauer

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

References

Bahramian A, Shariati A, Azimi T, Sharahi JY, Bostanghadiri N, Gachkar L et al (2019) First report of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-6 (NDM-6) among Klebsiella pneumoniae ST147 strains isolated from dialysis patients in Iran. Infect Genet Evol. 69:142–145

Pormohammad A, Nasiri MJ, Azimi T (2019) Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli strains simultaneously isolated from humans, animals, food, and the environment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Drug Resist 12:1181

Azimi L, Fallah F, Karimi A, Shirdoust M, Azimi T, Sedighi I et al (2020) Survey of various carbapenem-resistant mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from clinical samples in Iran. Iran J Basic Med Sci 23(11):1396

Bahramian A, Khoshnood S, Shariati A, Doustdar F, Chirani AS, Heidary M (2019) Molecular characterization of the pilS2 gene and its association with the frequency of Pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid pKLC102 and PAPI-1 pathogenicity island. Infect Drug Resist 12:221

Chang HH, Cohen T, Grad YH, Hanage WP, O’Brien TF, Lipsitch M (2015) Origin and proliferation of multiple-drug resistance in bacterial pathogens. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 79(1):101–116

Exner M, Bhattacharya S, Christiansen B, Gebel J, Goroncy-Bermes P, Hartemann P et al (2017) Antibiotic resistance: what is so special about multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria? GMS Hyg. Infect Control. 12:Doc05–DoDoc

Mulvey MR, Simor AE (2009) Antimicrobial resistance in hospitals: how concerned should we be? CMAJ. 180(4):408–415

Fallah F, Azimi T, Azimi L, Karimi A, Rahbar M, Shirdoust M et al (2020) Evaluating the antimicrobial resistance and frequency of AmpC β-lactamases blaCMY-2 gene in Gram-negative bacteria isolates collected from selected hospitals of Iran: a multicenter retrospective study. Gene Reports. 21:100868

Rubin J, Mussio K, Xu Y, Suh J, Riley LWJMDR (2020) Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance genes and integrons in commensal Gram-negative bacteria in a college community

Garneau-Tsodikova S, Labby KJ (2016) Mechanisms of resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics: overview and perspectives. Medchemcomm. 7(1):11–27

Teixeira B, Rodulfo H, Carreno N, Guzman M, Salazar E, Donato MD (2016) Aminoglycoside resistance genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Cumana, Venezuela. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo 58

Poole K. Aminoglycoside resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. 2005;49(2):479-487.

Niu H, Yu H, Hu T, Tian G, Zhang L, Guo X, et al. (2016) The prevalence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme and virulence genes among enterococci with high-level aminoglycoside resistance in Inner Mongolia, China. Braz J Microbiol 47:691-696

Ghotaslou R, Yeganeh Sefidan F, Akhi MT, Asgharzadeh M, Asl YM (2017) Dissemination of genes encoding aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and armA among Enterobacteriaceae isolates in Northwest Iran. Microb Drug Resist 23(7):826–832

Bodendoerfer E, Marchesi M, Imkamp F, Courvalin P, Böttger EC, Mancini S (2020) Co-occurrence of aminoglycoside and β-lactam resistance mechanisms in aminoglycoside-non-susceptible Escherichia coli isolated in the Zurich area, Switzerland. Int J Antimicrob Agents 56(1):106019

Mahdiyoun SM, Kazemian H, Ahanjan M, Houri H, Goudarzi M (2016) Frequency of aminoglycoside-resistance genes in methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates from hospitalized patients. Jundishapur J Microbiol 9(8):e35052–e3505e

Ramirez MS, Tolmasky ME (2010) Aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. Drug Resist Updat. 13(6):151–171

Azimi T, Maham S, Fallah F, Azimi L, Gholinejad Z (2019) Evaluating the antimicrobial resistance patterns among major bacterial pathogens isolated from clinical specimens taken from patients in Mofid Children’s Hospital, Tehran, Iran: 2013–2018. Infect Drug Resist 12:2089

Abo-State MAM, Saleh YE-S, Ghareeb HM (2018) Prevalence and sequence of aminoglycosides modifying enzymes genes among E. coli and Klebsiella species isolated from Egyptian hospitals. J Radiat Res Appl Sci. 11(4):408–415

Nasiri G, Peymani A, Farivar TN, Hosseini P (2018) Molecular epidemiology of aminoglycoside resistance in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae collected from Qazvin and Tehran provinces, Iran. Infect Genet Evol 64:219–224

Peerayeh SN, Rostami E, Siadat SD, Derakhshan S (2014) High rate of aminoglycoside resistance in CTX-M-15 producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in Tehran, Iran. Lab Med 45(3):231–237

Mir AR, Bashir Y, Dar FA, Sekhar M (2016) Identification of genes coding aminoglycoside modifying enzymes in E. coli of UTI patients in India. Sci World J 2016:1875865

Padmasini E, Padmaraj R, Ramesh SS (2014) High level aminoglycoside resistance and distribution of aminoglycoside resistant genes among clinical isolates of Enterococcus species in Chennai, India. Sci World J 2014

Krause KM, Serio AW, Kane TR, Connolly LE Aminoglycosides: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6(6):a027029

Armin S, Fallah F, Karimi A, Shirdoust M, Azimi T, Sedighi I et al (2020) Frequency of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase genes and antibiotic resistance patterns of Gram-negative bacteria in Iran: a multicenter study. Gene Reports. 21:100783

Vakulenko SB, Mobashery S (2003) Versatility of aminoglycosides and prospects for their future. Clin Microbiol Rev. 16(3):430–450

Aliakbarzade K, Farajnia S, Karimi Nik A, Zarei F, Tanomand A (2014) Prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance genes in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. Jundishapur J Microbiol 7(10):e11924–e1192e

Maes P, Vanhoof R (1992) A 56-month prospective surveillance study on the epidemiology of aminoglycoside resistance in a Belgian general hospital. Scand J Infect Dis 24(4):495–501

Hammond J, Potgieter PD, Forder AA, Plumb H (1990) Influence of amikacin as the primary aminoglycoside on bacterial isolates in the intensive care unit. 18(6):607–610

Strateva T, Yordanov D (2009) Pseudomonas aeruginosa–a phenomenon of bacterial resistance. J Med Microbiol 58(9):1133–1148

Mendes RE, Castanheira M, Toleman MA, Sader HS, Jones RN, Walsh TR et al (2007) Characterization of an integron carrying blaIMP-1 and a new aminoglycoside resistance gene, aac (6′)-31, and its dissemination among genetically unrelated clinical isolates in a Brazilian hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51(7):2611–2614

Sánchez-Martinez G, Garza-Ramos UJ, Reyna-Flores FL, Gaytán-Martínez J, Lorenzo-Bautista IG, Silva-Sanchez J (2010) In169, a new class 1 integron that encoded blaimp-18 in a multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate from Mexico. Arch Med Res 41(4):235–239

Zaunbrecher MA, Sikes RD Jr, Metchock B, Shinnick TM, Posey JE (2009) Overexpression of the chromosomally encoded aminoglycoside acetyltransferase eis confers kanamycin resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106(47):20004–20009

Reeves AZ, Campbell PJ, Sultana R, Malik S, Murray M, Plikaytis BB et al (2013) Aminoglycoside cross-resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis due to mutations in the 5' untranslated region of whiB7. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57(4):1857–1865

Awad A, Arafat N, Elhadidy M (2016) Genetic elements associated with antimicrobial resistance among avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 15(1):1–8

McGann P, Courvalin P, Snesrud E, Clifford RJ, Yoon E-J, Onmus-Leone F et al (2014) Amplification of aminoglycoside resistance gene aphA1 in Acinetobacter baumannii results in tobramycin therapy failure. MBio. 5(2):e00915–14

Kashfi M, Hashemi A, Eslami G, Amin MS, Tarashi S, Taki E (2017) The prevalence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes among Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from burn patients. Arch Clin Infect Dis 12(1):e40896

Aliakbarzade K, Farajnia S, Nik AK, Zarei F, Tanomand A (2014) Prevalence of aminoglycoside resistance genes in Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. Jundishapur J Microbiol 7(10):e11924

Aghazadeh M, Rezaee MA, Nahaei MR, Mahdian R, Pajand O, Saffari F et al (2013) Dissemination of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and 16S rRNA methylases among acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Microb Drug Resist 19(4):282–288

Gholami M, Haghshenas M, Moshiri M, Razavi S, Pournajaf A, Irajian G et al (2017) Frequency of 16S rRNA methylase and aminoglycoside-modifying enzyme genes among clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii in Iran. Iran J Pathol. 12(4):329–338

Soleimani N, Aganj M, Ali L, Shokoohizadeh L, Sakinc T (2014) Frequency distribution of genes encoding aminoglycoside modifying enzymes in uropathogenic E. coli isolated from Iranian hospital. BMC Research. Notes. 7(1):842

Lindemann PC, Risberg K, Wiker HG, Mylvaganam HJA (2012) Aminoglycoside resistance in clinical Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Western Norway. Apmis 120(6):495–502

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this publication was supported by Elite Researcher Grant Committee under award number [940290] from the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD), Tehran, Iran.

Nucleotide accession number(s)

The nucleotide sequences of the aac (6')-Ib, aph (3')-Ia, aph (6), aph (3')-II, and aadA15 genes, from E. coli strain, have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers MZ345706-MZ345710, and the nucleotide sequences of the aph (3')-VIe gene, from A. baumannii strain, have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers MZ345711.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Leila Azimi and Fatemeh Fallah: conceptualization and data curation. Hossein Samadi Kafil and Shahnaz Armin: formal analysis and writing—original draft. Fatemeh Fallah, Nafiseh Abdollahi, Kiarash Ghazvini, Sedigheh Rafiei Tabatabaei, and Lela Azimi: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, and writing—original draft. Shahram Shahraki Zahedani, Leila Azimi, and Fatemeh Fallah: data curation, formal analysis, writing the original draft, and writing review and editing. Nafiseh Abdollahi and Leila Azimi: language editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pediatric Infections Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU), Tehran, Iran (IR. NIMAD. REC1394.001).

Consent for publication

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. They played an active role in drafting the article or revising it critically to achieve important intellectual content, gave the final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary information.

The hospital origin of all clinical samples.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 1

. Primers used for the detection of genes encoding AMEs.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 2.

Frequency of GNB among different clinical samples in pediatric and general hospitals of Iran.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table 3

. The frequency of GNB isolated from clinical samples by different age groups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azimi, L., Armin, S., Samadi Kafil, H. et al. Evaluation of phenotypic and genotypic patterns of aminoglycoside resistance in the Gram-negative bacteria isolates collected from pediatric and general hospitals. Mol Cell Pediatr 9, 2 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-022-00134-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-022-00134-2