Abstract

Background

Mutations in the leptin gene (LEP) can alter the secretion or interaction of leptin with its receptor, leading to extreme early-onset obesity. The purpose of this work was to estimate the prevalence of heterozygous and homozygous mutations in the leptin gene with the help of the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/about).

Results

The ExAC database encompasses exome sequencing data from 60,706 individuals. We searched for listed leptin variants and identified 36 missense, 1 in-frame deletion, and 3 loss-of-function variants. The functional relevance of these variants was assessed by the in silico prediction tools PolyPhen-2, Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT), and Loss-Of-Function Transcript Effect Estimator (LOFTEE). PolyPhen-2 predicted 7 of the missense variants to be probably damaging and 10 to be possibly damaging. SIFT predicted 7 of the missense variants to be deleterious. Three loss-of-function variants were predicted by LOFTEE. Excluding double counts, we can summarize 21 variants as potentially damaging. Considering the allele count, we identified 31 heterozygous but no homozygous subjects with at least probably damaging variants. In the ExAC population, the estimated prevalence of heterozygous carriers of these potentially damaging variants was 1:2000. The probability of homozygosity was 1:15,000,000.

We furthermore tried to assess the functionality of ExAC-listed leptin variants by applying a knowledge-driven approach. By this approach, additional 6 of the ExAC-listed variants were considered potentially damaging, increasing the number of heterozygous subjects to 58, the prevalence of heterozygosity to 1:1050, and the probability of homozygosity to 1:4,400,000.

Conclusion

Using exome sequencing data from ExAC, in silico prediction tools and by applying a knowledge-driven approach, we identified 27 probably damaging variants in the leptin gene of 58 heterozygous subjects. With this information, we estimate the prevalence for heterozygosity at 1:1050 corresponding to an prevalence of homozygosity of 1:4,400,000 in this large pluriethnic cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The brain is the central regulator of body weight by balancing energy intake and expenditure. Both genetic and environmental factors affect this balance with underweight and obesity as extreme outcomes of its disturbance.

The rapid development of faster and cheaper sequencing methods enables the identification of rare monogenic disease including variants causing disturbances in weight regulation via impaired leptin-melanocortin signaling [1]. Some important monogenic forms are caused by mutations in, e.g., leptin (LEP), the leptin receptor (LEPR), pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), the signaling component Src homology 2B adapter protein 1 (SH2B1), or the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for details). The estimated prevalence of mutations causing monogenic forms of obesity ranges from 1 to 5% in severely obese subjects, with mutations in MC4R being most common [2].

The exact prevalence of variants in the gene-encoding leptin (LEP) is not known. In contrast to, e.g., MC4R variants, pathological leptin deficiency occurs only in subjects with biallelic mutations. In 1997, Montague et al. were the first to describe two subjects with a homozygous mutation in the leptin gene. This frameshift mutation, p.Gly133Valfs*15, is deemed to be underproduced due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay and not secreted due to aberrant cellular transport [3] (see Fig. 1c). In the affected subjects, the disturbance of the leptin-melanocortin pathway led to extreme early-onset obesity as well as metabolic disorders, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, and suppressed immune function [3,4,5,6]. In 2015, we described the existence of biologically inactive leptin due to missense mutations (p.Asp100Tyr and p.Asn103Lys, see Fig. 1d) [7, 8]. Up to now, 53 subjects affected by leptin gene variants with either proven or suggested functional disturbance have been described in the literature (see Additional file 1: Table S2) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, 21, 22, 47]. It should be noted that there might be several cases which are either not diagnosed or not published hampering the estimation of prevalence via literature analysis. Identifying monogenic forms of obesity is a psychological relief for the patient and relatives, sometimes enabling treatment with, e.g., metreleptin or setmelanotide [7, 10, 23,24,25]. In our outpatient clinic, we encounter almost daily patients struggling with extreme obesity, and the pediatricians face the question if cost-intensive sequencing is required. With this work, we aim to estimate the prevalence of heterozygous and homozygous mutations in the leptin gene with the help of the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database. Taking congenital leptin deficiency as our example, we moreover want to outline this database as a helpful tool to estimate the prevalence of rare monogenetic diseases [26]. Conversely, we want to analyze the allele frequency of published mutations in the leptin gene, known to cause severe obesity when inherited homozygously.

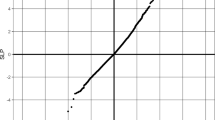

Pathologies in the leptin and leptin receptor pathway. Simplified representation of the secretion of leptin in the adipocytes and the interaction with the leptin receptor in the hypothalamus. a Regular function of leptin. Following secretion from adipocytes, leptin can activate the hypothalamic leptin receptor which reduces food intake and results in decreases in adipocyte volume and body fat. b–d Functional defects of leptin or the leptin receptor result in uncontrolled food intake and increases in adipocyte volume and body fat. Mutations can either affect the leptin receptor (b), the production and secretion of leptin (c), or the interaction of leptin with its receptor (d)

Methods

ExAC

The ExAC database (http://ExAC.broadinstitute.org/; Accessed: 25 April 2017) collects exome sequencing data from worldwide studies including data from, e.g., the 1000 Genomes Project. Further information on participating studies and ethnic distribution are available in the FAQ of the ExAC database (http://ExAC.broadinstitute.org/faq). After exclusion of, e.g., low quality data, related individuals, and individuals with severe pediatric disease, data was available from 60,706 individuals with a lack of data from Middle Eastern and Central Asian populations. All data is based on the human genome assembly GRCh37/hg19. The mean coverage for the leptin gene was ~ 80× [26].

Variants in the LEP and their functional analysis

We searched the gene of interest (Leptin/LEP, canonical transcript ENST00000308868) and focused on missense and loss-of-function (LoF) variants.

ExAC provides more detailed information on each variant such as ethnical distribution and allele frequency. Using in silico models, namely PolyPhen-2 (Polymorphism Phenotyping v2), SIFT (Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant), and LOFTEE (Loss-Of-Function Transcript Effect Estimator), ExAC estimates the impact of a given variant on protein function.

PolyPhen-2 categorizes the variants in three groups: benign, possibly damaging, and probably damaging. SIFT categorizes in two groups: tolerated and deleterious. Single nucleotide changes in splice acceptor/splice donor side and nonsense variants were labeled as LoF and analyzed with the help of LOFTEE (see Additional file 1: Table S3).

In addition, we estimated the function of leptin variants by applying a knowledge-driven approach, based on findings described in mutagenesis studies. Leptin has three binding sides (BS). The role of BS I is yet undefined but is unlikely to be involved in interactions with the functional leptin receptor isoform. BS II is needed for receptor binding, whereas BS III is required for signaling [27,28,29]. Variants located close to those binding sites (accepted distance ≤ 4 amino acids) or nearby the disulfide bond in position of cysteines 117 and 167 of the immature protein required for structural stability were classified as potentially functionally damaging [28, 30,31,32]. We did not distinguish between different chemical properties of the amino acids. In addition, it cannot be excluded that variants in other areas may alter the transcription and therefore the function of the protein.

Based on these findings, we calculated the probability of hetero- and homozygosity with the binominal distribution predicted by the Hardy-Weinberg principle assuming a perfect population. p2 + 2pq + q2 = 1 (p = allele frequency of allele A; q = allele frequency of allele B).

We compiled a list of subjects homozygous for leptin variants and severe obesity based on literature research (PubMed, OMIM). With the help of the ExAC browser, we looked for the allele frequency of these variants [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18, 21, 22, 47].

Results

The functional relevance of variants in the leptin gene listed in ExAC was assessed by the in silico prediction tools PolyPhen-2, SIFT, and LOFTEE. PolyPhen-2 predicted 10 of the missense variants to be possibly damaging and 7 to be probably damaging. SIFT predicted seven of the missense variants to be deleterious. Three LoF variants were predicted by LOFTEE (see Additional file 1: Table S3).

Our own analysis revealed 6 additional variants to be located closer than ≤ 4 amino acids to BS II, BS III, or the disulfide bond (p. Ile35del, p.Lys36Arg, p.Ile45Val; p.Ile63Leu, p.Ala137Ser, p.Gly166Arg) and therefore potentially damaging. None of those 6 variants was predicted as functionally disturbing by in silico models used in ExAC.

Based solely on PolyPhen-2, SIFT, and LOFTEE analyses (excluding double counts), we can summarize 21 variants as potentially damaging. Considering the allele count, we identified 31 heterozygous but no homozygous subjects with variants predicted to be at least probably damaging in ExAC. With this, the estimated prevalence of heterozygosity was ≈1:2000 and the corresponding probability of homozygosity was ≈1:15,000,000 in the ExAC population.

When we included the 6 variants deemed to be potentially damaging by our own functional assessment, we identified 58 heterozygous subjects increasing the prevalence of heterozygosity to ≈1:1050 and the corresponding probability of homozygosity of ≈1: 4,400,000.

Summarizing the data from the literature of homozygous severely obese subjects with a homozygous LEP mutation, we identified 53 subjects with 12 distinct variants in the leptin gene. Of the identified variants, 6 were missense, 1 was an in-frame deletion, and 5 were LoF variants (see Additional file 1: Table S2). Only three of those variants are listed in ExAC database (p.Gly133Valfs*15, p.Asn103Lys and p.Ile35del; see Table 1) and described as functionally damaging. From the 12 variants reported in the literature, p.G133Vfs*15 is the most frequent with 30 affected subjects, all of Pakistani origin, suggesting that it constitutes a founder mutation. In accordance with this, p.G133Vfs*15 displayed the highest allele count (of mutations described in the literature) localized exclusively in South Asian population in ExAC.

Discussion

The ExAC database is a tool with which one can predict if a gene variant is a polymorphism or a functionally damaging variant that may be a disease-causing mutation. Exemplifying this, roughly 200 variants that were previously believed to be disease-causing mutations were now revealed to be mostly harmless polymorphisms by use of the database [26, 34]. In 2017, ExAC aims to add 120,000 exome and 20,000 whole genome sequences [26]. ExAC is a helpful tool to avoid cost-/time-intensive screenings and misinterpretations of detected variants. Nevertheless, ExAC has some limitations. Studies, which provided the data, screened mostly cohorts with specific underlying disease, e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, type 2 diabetes, or schizophrenia (further information about the used cohorts can be looked up in the FAQ section of the website http://exac.broadinstitute.org/faq), and thus represent a selected population. Subjects with severe pediatric disease were excluded. This inevitably leads to exclusion of some variants causing severe autosomal dominant disease. ExAC used cohorts throughout the world. Still, there is a lack of information from the Middle Eastern and Central Asian population. This data would especially be interesting for the leptin gene considering that most described cases with monogenic leptin deficiency are from Middle Eastern origin [3, 9, 10, 13, 14, 17, 18].

It should also be noted that ExAC does not include variants with larger deletions or duplications due to technical reasons. At this point of time, ExAC does not provide information about phenotypic characteristics such as BMI for ethical reasons. Finally, the validity of PolyPhen-2/SIFT/LOFTEE is based on in silico predictions and is thus somehow limited and can hardly replace functional in vitro studies [3, 6, 7]. The p.Ile35del variant for instance, was not predicted as functionally damaging; however, it is described in Fatima et al. and Saeed et al. to provoke obesity in homozygous conditions [13, 16]. We note that other algorithms for predicting the effects of missense variants exist (see, e.g., the programs referenced on https://omictools.com/functional-predictions-category) as well as another (larger) exome and genome sequence database, gnoMAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/).

With regard to the leptin gene, we note that pathological leptin deficiency occurs only in subjects with biallelic mutations and is therefore much less frequent than, e.g., MC4R mutation (which can lead also in the heterozygous status to disease manifestation). There is no evidence for a pathogenic phenotype in subjects with heterozygous LEP mutations. We also note that our estimation does not account for compound heterozygous LEP mutations that may cause severe obesity.

We conclude that the estimated prevalence for homozygous leptin variants is very low at one case in 15 million (ExAC) or 4.4 million (including our analysis). Practically this should demonstrate that the leptin gene is not a candidate for routine genetic screening in obese patients, but it will probably be included in multigene panels for monogenic obesity. This holds true especially as leptin deficiency, although rare, has therapeutic consequences. We therefore consider more refined clinical criteria for preliminary investigation before time- and cost-intensive genetic screening including the survey of weight development in early childhood and a recently developed assay enabling the measurement of bio-active leptin (see Fig. 1d) [35].

Conclusion

ExAC is a unique collection of data comprising a high variety of ethnicities. It constitutes a free resource that simplifies the access to exome sequence data remarkably. It is a user-friendly tool which a clinician in cooperation with a genetic laboratory can easily apply in his daily routine to estimate the prevalence of variants. Using exome sequencing data from ExAC, in silico prediction tools and a knowledge-driven approach, we identified 27 probably damaging variants in the leptin gene of 58 heterozygous subjects. With this information we estimate the prevalence for heterozygosity at 1:1050 corresponding to an prevalence of homozygosity of 1:4,400,000 in this large pluriethnic cohort.

Diagnosing a mutation causing monogenic obesity will enable pharmacological treatment in some instances and is a psychological relief for the patient and the relatives. To facilitate its diagnosis, available information on variants in the leptin gene should be harmonized with associated phenotypic characteristics in a structured and comprehensive way by establishing an international registry for this rare disease.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BS:

-

Binding Side

- Del:

-

Deletion

- ExAC:

-

Exome aggregation consortium

- FAQ:

-

Frequently asked questions

- LEP:

-

Leptin gene

- LOFTEE:

-

Loss-of-Function Transcript Effect Estimator

- MC4R:

-

Melanocortin 4 receptor

- PolyPhen-2:

-

Polymorphism phenotyping v2

- SIFT:

-

Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant

References

Farooqi IS, O'Rahilly S (2014) 20 years of leptin: human disorders of leptin action. J Endocrinol 223(1):T63–T70

van der Klaauw AA, Farooqi IS (2015) The hunger genes: pathways to obesity. Cell 161(1):119–132

Montague CT et al (1997) Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature 387(6636):903–908

Strobel A et al (1998) A leptin missense mutation associated with hypogonadism and morbid obesity. Nat Genet 18(3):213–215

Ozata M, Ozdemir IC, Licinio J (1999) Human leptin deficiency caused by a missense mutation: multiple endocrine defects, decreased sympathetic tone, and immune system dysfunction indicate new targets for leptin action, greater central than peripheral resistance to the effects of leptin, and spontaneous correction of leptin-mediated defects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84(10):3686–3695

Fischer-Posovszky P et al (2010) A new missense mutation in the leptin gene causes mild obesity and hypogonadism without affecting T cell responsiveness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(6):2836–2840

Wabitsch M et al (2015) Biologically inactive leptin and early-onset extreme obesity. N Engl J Med 372(1):48–54

Wabitsch M et al (2015) Severe early-onset obesity due to bioinactive leptin caused by a p.N103K mutation in the leptin gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100(9):3227–3230

Farooqi IS et al (2002) Beneficial effects of leptin on obesity, T cell hyporesponsiveness, and neuroendocrine/metabolic dysfunction of human congenital leptin deficiency. J Clin Invest 110(8):1093–1103

Gibson WT et al (2004) Congenital leptin deficiency due to homozygosity for the Delta133G mutation: report of another case and evaluation of response to four years of leptin therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89(10):4821–4826

Farooqi IS (2008) Monogenic human obesity. Front Horm Res 36:1–11

Mazen I et al (2009) A novel homozygous missense mutation of the leptin gene (N103K) in an obese Egyptian patient. Mol Genet Metab 97(4):305–308

Fatima W et al (2011) Leptin deficiency and leptin gene mutations in obese children from Pakistan. Int J Pediatr Obes 6(5-6):419–427

Saeed S et al (2012) High prevalence of leptin and melanocortin-4 receptor gene mutations in children with severe obesity from Pakistani consanguineous families. Mol Genet Metab 106(1):121–126

Saeed S et al (2014) Changes in levels of peripheral hormones controlling appetite are inconsistent with hyperphagia in leptin-deficient subjects. Endocrine 45(3):401–408

Mazen I et al (2014) A novel mutation in the leptin gene (W121X) in an Egyptian family. Mol Genet Metab Rep 1:474–476

Saeed S et al (2015) Genetic variants in LEP, LEPR, and MC4R explain 30% of severe obesity in children from a consanguineous population. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23(8):1687–1695

Shabana, Hasnain S (2016) The p. N103K mutation of leptin (LEP) gene and severe early onset obesity in Pakistan. Biol Res 49:23

Zhao Y et al (2014) A novel mutation in leptin gene is associated with severe obesity in Chinese individuals. Biomed Res Int 2014:ID 912052

Vaisse C et al (1998) A frameshift mutation in human MC4R is associated with a dominant form of obesity. Nat Genet 20(2):113–114

Thakur S et al (2014) A novel mutation of the leptin gene in an Indian patient. Clin Genet 86(4):391–393

Paz-Filho GJ et al (2008) Leptin replacement improves cognitive development. PLoS One 3(8):e3098

von Schnurbein J et al (2012) Leptin substitution results in the induction of menstrual cycles in an adolescent with leptin deficiency and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Horm Res Paediatr 77(2):127–133

Farooqi IS et al (1999) Effects of recombinant leptin therapy in a child with congenital leptin deficiency. N Engl J Med 341(12):879–884

Kühnen P et al (2016) Proopiomelanocortin deficiency treated with a Melanocortin-4 receptor agonist. N Engl J Med 375(3):240–246

Lek M et al (2016) Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536(7616):285–291

Peelman F et al (2006) Mapping of binding site III in the leptin receptor and modeling of a hexameric leptin. Leptin receptor complex. J Biol Chem 281(22):15496–15504

Peelman F et al (2014) 20 years of leptin: insights into signaling assemblies of the leptin receptor. J Endocrinol 223(1):T9–23

Niv-Spector L et al (2005) Identification of the hydrophobic strand in the A-B loop of leptin as major binding site III: implications for large-scale preparation of potent recombinant human and ovine leptin antagonists. Biochem J 391(Pt 2):221–230

Haglund E et al (2012) The unique cysteine knot regulates the pleotropic hormone leptin. PLoS One 7(9):e45654

Rock F et al (1996) The liptin haemopoietic cytokine fold is stabilized by an intrachain disulfide bond. Horm Metab Res 28(12):649–652

Boute N et al (2004) The formation of an intrachain disulfide bond in the leptin protein is necessary for efficient leptin secretion. Biochimie 86(6):351–356

Paz-Filho G et al (2010) Congenital leptin deficiency: diagnosis and effects of leptin replacement therapy. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 54(8):690–697

Piton A, Redin C, Mandel JL (2013) XLID-causing mutations and associated genes challenged in light of data from large-scale human exome sequencing. Am J Hum Genet 93(2):368–383

Wabitsch M et al. (2016) Measurement of immunofunctional leptin to detect and monitor patients with functional leptin deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol 176:315–22.

Clement K et al (1998) A mutation in the human leptin receptor gene causes obesity and pituitary dysfunction. Nature 392(6674):398–401

Farooqi IS et al (2007) Clinical and molecular genetic spectrum of congenital deficiency of the leptin receptor. N Engl J Med 356(3):237–247

Maures TJ, Kurzer JH, Carter-Su C (2007) SH2B1 (SH2-B) and JAK2: a multifunctional adaptor protein and kinase made for each other. Trends Endocrinol Metab 18(1):38–45

Mazen I et al (2011) Homozygosity for a novel missense mutation in the leptin receptor gene (P316T) in two Egyptian cousins with severe early onset obesity. Mol Genet Metab 102(4):461–464

Pearce LR et al (2014) Functional characterization of obesity-associated variants involving the alpha and beta isoforms of human SH2B1. Endocrinology 155(9):3219–3226

Jackson RS et al (1997) Obesity and impaired prohormone processing associated with mutations in the human prohormone convertase 1 gene. Nat Genet 16(3):303–306

Farooqi IS et al (2006) Heterozygosity for a POMC-null mutation and increased obesity risk in humans. Diabetes 55(9):2549–2553

Hinney A et al (1999) Several mutations in the melanocortin-4 receptor gene including a nonsense and a frameshift mutation associated with dominantly inherited obesity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84(4):1483–1486

List JF, Habener JF (2003) Defective melanocortin 4 receptors in hyperphagia and morbid obesity. N Engl J Med 348(12):1160–1163

Vollbach H et al (2017) Prevalence and phenotypic characterization of MC4R variants in a large pediatric cohort. Int J Obes 41(1):13–22

Yeo GS et al (1998) A frameshift mutation in MC4R associated with dominantly inherited human obesity. Nat Genet 20(2):111–112

Chekhranova MK et al (2008) A new mutation c.422C>G (p.S141C) in homo and heterozygous forms of the human leptin gene. Russ J Bioorg Chem 34(6):768–770

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NA is the author of the first draft of the manuscript and provided substantial contributions to conception and design and acquisition of data analysis and interpretation of data. BG and FJB provided substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript critically, and approved the final version to be published. KK and SB provided substantial contributions to concept and design, revised the manuscript critically, and approved the final version to be published. AH conceived the initial idea of the project, revised the manuscript critically, and approved the final version to be published. MB, GP, KMD, and FPP revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version to be published. WM conceived the initial idea of the project, provided substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data, revised the manuscript critically, and approved the final version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

List of genes in which mutations were described to affect the leptin-melanocortin signaling pathway [3, 6, 7, 9, 20, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Table S2. Leptin gene variants described in the literature. Reference sequence for c.DNA: NM_000230/ Transcript ID: ENST00000308868.4 [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19, 21, 22, 33, 47]. Table S3. Summary of missense and LoF variants in the leptin gene LEP listed in the ExAC database. Gray rows indicate mutations evaluated as probably functionally damaging by our own knowledge-driven functional assessment. (DOCX 69 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nunziata, A., Borck, G., Funcke, JB. et al. Estimated prevalence of potentially damaging variants in the leptin gene. Mol Cell Pediatr 4, 10 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-017-0074-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40348-017-0074-x