Abstract

Background

The relationship between the health care provider and the patient is an indispensable element of medical care. The existence of a proper therapeutic relationship between the health care provider and the patient can increase patients’ trust and willingness to communicate, improve adherence to medical recommendations, enhance continuing care, and promote patient satisfaction. However, little is known in developing countries including Ethiopia what the patient health care provider relationship looks like. This study aimed to assess the health care provider-patient relationship during preoperative care in obstetric and gynecologic surgeries at Jimma Medical Center, Jimma, Ethiopia.

Methods

Institution-based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 1 to May 30, 2020, at Jimma Medical Center. A total of 372 surgical patients were selected using a systematic random sampling method. The collected data were coded, entered into Epi data version 3.1, and analyzed using the statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 25. Bivariate and multivariable regression was carried out to determine the association between the outcome variable and the independent variable. The strength of association of dependent and independent variables was presented by crude and adjusted odds ratio at a 95% confidence interval. Variables with a p value of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The proportion of good patient to health care provider relationship in this study was 179 (48%) and it had a significant association with patient marital status AOR = 0.29 (95% CI 0.147–0.580), consent form available AOR = 0.162 (95% CI 0.035–0.750), the profession of healthcare providers who request the consent AOR = 0.305 (95% CI 0.117–.794), mode of decision-making AOR = 0.165 (95% CI 0.039–.709), and patient’s satisfaction AOR = 5.34(95% CI 3.1–9.16).

Conclusions

The proportion of patient-to healthcare providers’ relationship was low. More than half of the respondents did not have good patient–health care provider relationship. Hence, health care providers should be concerned about their relationship with their patients to increase the quality of medical care. The health care providers should bear in mind that patients may refuse to seek care from a provider whose relationship is not strong, even if the provider is skilled in preventing and managing complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The patient-health care provider can be defined as the patient perception of the caring shown by the health care provider as well as the attitude and behavior of the health care provider towards the patient. It is one of the indispensable elements of medical care (Kalateh et al., 2014). A good healthcare provider–patient relationship can increase patients’ trust and willingness to communicate, improve adherence to medical recommendations, enhance continuing care, and promote patient satisfaction (Kalateh et al., 2014; Rolfe et al., 2014; Chou & Lin, 2012). It also forms the basis for the cooperation between the patient and the health care provider and helps to avoid misunderstandings between the two parties (Schneider & Ulrich, 2008). The health care provider–patient relationship is important for correct communication with the patient. Right communication with the patient needs that the patient is not simply a group of symptoms and out of action organs; however, the medical practitioner ought to see the patient together with his or her specific issues and needs sought-after facilitate and improvement confidently and trust to him or her (Asemani, 2012). Research done in China revealed that several complaints do not relate to the doctors’ scientific skills and effectualness, however, rather to a way to communicate with the patient (Hossein et al., 2010).

Over the past few years, improvement in life science and medical technology has created treatments simpler. However, patient-provider relationships (PPR) have step by step deteriorated round the world (Nagral et al., 2016; Thielscher & Schulte-Sutrum, 2016; Cernadas, 2016; Bascuñán, 2005). In China, the deteriorated PPR has caused an oversized vary of medical disputes between the patients and care suppliers, primarily doctors and nurses, with some extreme cases involving violence towards providers (Wang et al., 2012). Understanding the factors that influence the healthcare provider-patient relationship may assist healthcare professionals in identifying patients who have a poor relationship during this regard. However, very little is understood regarding the factors influencing the health care provider-patient relationship in developing countries including Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was aimed to explore the factors affecting the relationship between the healthcare provider and patient in Jimma Medical Center, Jimma, Ethiopia, among women who have underwent obstetrics and gynecologic surgeries.

Methods and material

Study setting, design, and period

A cross-sectional study was conducted in Jimma Medical Center located in Jimma town. Jimma town is situated about 354 km away from Addis Ababa; the capital city of Ethiopia. Around 1461 and 900 patients undergone obstetric and gynecological-related surgery within the past 6 months respectively (the previous 6-month report). The study period was from April 1 to May 30, 2020.

Study population

All women who underwent obstetrics and gynecologic surgeries were the source population of the study. Selected women who underwent obstetrics and gynecologic surgeries were the study population of the study.

Eligible criteria

Inclusion criteria

Women who underwent obstetrics and gynecology (Ob-Gyn) surgery age 18 years old and above were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria

Women who were critically ill and with known psychiatric illnesses were excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula by considering 59.3% proportion (P) which took from research done in Calabar Teaching Hospital, Nigeria (Udonwa & Ogbonna, 2012); with a 95% confidence interval (1.96); α = 0.05 and 5% marginal of error.

By adding a non-response rate of 5%, the final sample size was 390.

Sampling technique

A systematic sampling technique was employed to select study participants from 798 total 2-month surgical cases after determining the interval (Kth). The k-interval was determined by dividing the total 2-month surgical case (798) by the final sample size (390) that was given approximately 2. The first study participant was selected by lottery method using their registration serial number and then the rest were selected every kth interval (2) from the registration book until the final sample size was reached.

Data collection methods and tools

Data were collected using a pretested, structured, and closed-ended questionnaire. The data collection method was using an interviewer-administered questionnaire and document review. The questionnaires have six parts. The first part deals with general socio-demographic which consists of 8 items. The second part deals with patient-related factors which consists of 7 items; service-related factors consists of 8 items. The fourth part deals with a recommended component of informed consent which consists of 13 items. The fifth part deals with patient to healthcare provider relationship which consists of 9 items, and the last sixth part deals about patients’ knowledge towards surgical informed consent. Two BSc and one MSc nurses were recruited as data collectors and supervisor respectively.

Study variables

Dependent variable

Patient to healthcare provider relationship

Independent variables

Social-demographic characteristics

Age, educational status, occupation, marital status, and residence.

Patient-related factors

Parity, knowledge, type of surgery, and previous surgery.

Service-related factors

Referred history, the language of the written consent form, profession who requested informed consent, the timing of consent, time taken to provide informed consent, time taken to decision-making, and person who signed on informed consent.

Practice surgical informed consent

Operational definition and definition of terms.

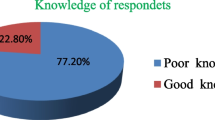

Knowledge on surgical informed consent

Deals about surgical informed consent if women answered knowledge questions with the above mean score consider good knowledge otherwise having poor knowledge (Bascuñán, 2005).

The practice of the recommended component of informed consent

Women who reported that received at least 6 out of 13 total recommend components of surgical informed consent (Thielscher & Schulte-Sutrum, 2016).

Patient-doctor relationship questionnaire (PDRQ)

This is a tool that contains 9 questions each with 5 possible responses. Each response assigned a score ranging from 1 to 5. The overall value of the scale ranges from 9 to 45. It has been validated for use in many developing countries including Ethiopia. In the current study, the internal consistency was found to be 0.86.based on mean score, a surgical patient with a score of 34.5 and less was considered as had poor relationship, while a mother with a PDRQ score of 34.5 and more were considered as a had good relationship (Wang et al., 2012).

Data analysis procedures

The collected data were coded and entered into Epi data 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 25. Descriptive analysis was used to explore socio-demographic characteristics, service-related factors, practice surgical informed consent, and patient-related factors. Bivariate and multivariable analyses were done between the patient healthcare provider relationship and independent variables. In bivariate logistic regression, the variables which had a p-value less than 0.25 was considered as candidate variable for multivariable logistic analysis. In multivariable analysis, those variables which had a p value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant with the outcome variable. The model goodness of fit was tested by using Hosmer-Lemeshow and Omnibus test and the p value was 0.52 and 0.001 respectively. The strength of association was determined using an odds ratio at a 95% confidence interval. The study findings were presented by using text, tables, figures, and graphs.

Data quality management

The questionnaire was initially prepared in English then translated to the local language (Afaan Oromo), then translated back to English. A pretest was done on 5% (25) of the sample size other than study subjects and 1-day training was given for data collectors and supervisors. During the data collection period, the data were checked for completeness and consistency of information by the principal investigator. Any error, ambiguity, incompleteness, or other problems were addressed through communication with data collectors before the beginning of the next day’s activities.

Ethical consideration

An ethical letter was obtained from the institutional review board of Jimma University. The ethical letter was submitted to Jimma Medical Center. After getting permission from the hospital, written consent was obtained from individual participants. Moreover, study participants were informed about the aim of the study and the data used only for research purposes. The data collection was done using anonymously to assured the respondents’ confidentiality. All the participants were told that their participation would be voluntary and their information will be kept in a secured manner.

Results

Socio-demographic variables

From a total of 390 women, 372 of them were involved in the study yielding giving a response rate of 95.4%. The majority of (89.1%) respondents were age below 35 years old, and 291 respondents were literate. The majority of (83.3%) respondents were married and 242 respondents were living in an urban place (Table 1).

Patient-related factors

Among the respondents one hundred sixty (43%) participants were primipara and 277 had undergone unplanned or emergency surgical procedures. The majority of participants had no prior medical or surgical history (330) and (269) respectively (Table 2).

Service-related factors

In this study, 352 study participants’ mode of decision-making was self-method of decision, and 302(81.2%) participants reported to have received SIC counseling from residents (Table 3).

Patient to healthcare provider’s relationship

In this study, 48% [95% CI (43.8–53.0%)] of study participants had good patient to health care provides relationship while 193(52%) [95% CI (47.0–53.2%)]) study participants have poor patient-healthcare provider’s relationship (Fig. 1).

Factors associated with patient to health care provider relationship

In the bivariate logistic regression analysis, 10 variables were candidates for multivariable logistic regression including respondent’s age, marital status, surgical history, consent form available, the profession of healthcare providers who request consent, time taken to decide on informed consent, mode of decision-making, patient’s satisfaction, the practice of surgical informed consent, and knowledge of surgical informed consent. However, in the multivariable logistic regression, only five variables had association with good patient-healthcare providers’ relationship including marital status AOR = 0.292 (95% CI 0.147–.580), written consent form available AOR = 0.162 (95% CI 0.035–.750), profession of healthcare providers who request consent AOR = 0.305 (95% CI 0.117–.794), mode of decision-making AOR = 0.165(95% CI 0.039–0.709), and patient’s satisfaction AOR = 5.34 (95% CI 3.117–9.162) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, the proportion of good patient-healthcare provider’s relationship was 48% [95% CI (43.8–53.0%)]. The finding was lower than the study done in Nigeria at the General Outpatient Clinic of the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (Udonwa & Ogbonna, 2012) and higher than the study done in three university teaching hospitals in Uganda on informed consent in clinical practice: patients’ experiences and perspectives following surgery (Ochieng et al., 2015). The possible reasons may be due to the difference in the health care setting and patient and physician proportion. Besides, this variation may be due to variation in medico-legal issues, provider motivation and satisfaction, and variation in the healthcare system.

In the present study, marital status was found to have a significant association with patient-health care providers’ relationship. Married respondents were 70.8% less likely to have patient-healthcare providers’ relationship than those participants with single marital status AOR .292 [95% CI (.147–.580)]. This may be due to the traditional belief in our community “husband knows best” and the decision-making role given to the husband. So this habit may lead the wife or patient to be a subordinate and poor relationship with her primary healthcare provider (Bako et al., 2011).

Study participants who report the availability of informed consent forms in the hospital during the surgical procedure were 84% less likely to have good patient healthcare providers’ relationship than counterpart AOR .162 [95% CI (.035–.750)]. This might be possible due to the availability of written surgical informed consent forms during a surgical procedure may lead the professional to focus only on information found on the form and may constrain the professional to discourse other consent options like verbal or oral informed consent. During verbal informed consent, there are two-way communications and it creates a better relationship with providers than the written one.

Another explanatory variable that had a significant association with a good patient-to-health provider relationship was the profession of healthcare providers who requested consent. The respondents who reported to have received SIC counseling from the resident or general practitioners were 69.5% less likely to have good patient healthcare providers’ relationship than respondents who reported to have surgical informed consent counseling from obstetrics/gynecology specialist. The possible reason might be due to patients may be highly interested to have a relation with a specialist who performs the procedure (surgery) than general practitioners.

Furthermore, the mode of decision-making during informed consent was significantly associated with patient-health care providers’ relationship. The consent form agreement decided through paternalism manner were 94% less likely have good patient to healthcare providers’ relationship than respondents who decided the agreement by themselves AOR = 0 .062 [95% CI (.006–.632)]. The possible reason may be due to paternalism type of decision making may not consider the patient interest and reduce the chance of relation between the patient and healthcare provider. That is why most of the time, shared decision-making is recommended (Barry & Edgman-Levitan, 2012).

Respondents’ satisfaction was another variable that had a significant association with patient-health care providers’ relationship. Study participants who were satisfied with the provision of surgical informed consent were five times more likely to have good patient-health care providers' relationship than counterpart AOR 5.344 [95% CI (3.117–9.162)]. This finding is consistent with another study’s finding conducted in Mongolia Autonomous Region, China on factors associated with the doctor-patient relationship (Qiao et al., 2019). This is possible since respondents who were satisfied with the health service received may be motivated to have a good relationship with the health care provider.

Strengths and limitations

Being the first to assess the situation in Ethiopia and the study area, in particular, is the major strength of the study. However, the respondents were interviewed after the operation. Due to this, the respondents might have forgotten information given to them during the informed consent provision. Also, the study shares all limitations of the cross-sectional study design.

Conclusions

Patient-to healthcare providers’ relationship was low when compared with the international recommendation and it had a significant association with marital status, consent form available, the profession of healthcare provider who requests consent, mode of decision making, and patient’s satisfaction were a significant association with independent variables. Hence, the health care providers should bear in mind that patients may refuse to seek care from a provider whose relationship is not solid, even if the provider is skilled in preventing and managing complications. Furthermore, the patient–provider relationship is the cornerstone of the medical profession and successful medical care requires ongoing collaboration between patients and physicians; a partnership in which both members take an active role in the healing process.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odd ratio

- COR:

-

Crude odd ratio

- JMC:

-

Jimma Medical Center

- SIC:

-

Surgical informed consent

- Ob-Gyn:

-

Obstetrics and gynecology

- PPR:

-

Patient–provider relationships

- PDRQ:

-

Patient–doctor relationship questionnaire

References

Asemani O. A review of the models of the physician-patient relationship and its challenges. Iran J Med Ethics History Med. 2012;5(4):36–50.

Bako B, Umar N, Garba N, Khan N. Informed consent practices and its implication for emergency obstetrics care in azare, north-eastern Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2011;1(2):149–58.

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—The pinnacle patient-centered care. 2012.

Bascuñán RM. Changes in physician-patient relationship and medical satisfaction. Revista Medica de Chile. 2005;133(1):11–6.

Cernadas JMC. Is it possible to revert doctor-patient relationship deterioration? 2016.

Chou P-L, Lin C-C. Cancer patients adherence and symptom management: the influence of the patient-physician relationship. Hu Li Za Zhi. 2012;59(1):11–5.

Hossein R, Azad R, Akram G. The viewpoint of nurses about professional relationship between nurses and physicians. J Res Develop Nurs Midwife. 2010;7(1):63–71.

Kalateh SA, Iman MT, Bagheri LK. Quality and Frequency of Human Fellow Voice used in Doctor-Patient Interaction (One Qualitative Study in Clinical Counseling). 2014.

Nagral S, Jain A, Nundy S. A radical prescription for the Medical Council of India. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2016.

Ochieng J, Buwembo W, Mumbai I, Ibingira C, Kiryowa H, Nzarubara G, et al. Informed consent in clinical practice: patients' experiences and perspectives following surgery. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):765. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1754-z.

Qiao T, Fan Y, Geater AF, Chongsuvivatwong V, McNeil EB. Factors associated with the doctor–patient relationship: doctor and patient perspectives in hospital outpatient clinics of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China. Patient Prefer Adher. 2019;13:1125–43. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S189345.

Rolfe A, Cash-Gibson L, Car J, Sheikh A, McKinstry B. Interventions for improving patients' trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004134.pub3.

Schneider U, Ulrich V. The physician-patient relationship revisited: the patient’s view. Int J Healthc Finance Econ. 2008;8(4):279–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10754-008-9041-3.

Thielscher C, Schulte-Sutrum B. Die Entwicklung der Arzt-Patienten-Beziehung in Deutschland in den letzten Jahren aus Sicht von Vertretern der Ärztekammern und der Kassenärztlichen Vereinigungen. Das Gesundheitswesen. 2016;17(01):8–13.

Udonwa NE, Ogbonna UK. Patient-related factors influencing satisfaction in the patient-doctor encounters at the general outpatient clinic of the University of Calabar teaching hospital, Calabar, Nigeria. Int J Fam Med. 2012;2012:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/517027.

Wang X-Q, Wang X-T, Zheng J-J. How to end violence against doctors in China. The Lancet. 2012;380(9842):647–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61367-1.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Jimma University, Jimma Medical Center staff, data collectors, supervisor, and patients for their co-operation during the data collection period.

Funding

There is no funding for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed in the study conception and design (methodology). Additionally, TB, BF, and AY were involved in data analysis, software, and writing the original draft. AT and YB contributed to the edition and supervision of the whole process of the work. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

To conduct this study, ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board (Ref. No. IRB 000165/2020) of Jimma University, Institute of Health. Written consent was obtained from each participant. Moreover, study participants were informed about the aim of the study and were told that the data would be used only for research purposes. Data collection was collected anonymously to assure the respondents’ confidentiality. All participants were told that their participation would be voluntary and their information will be kept in a secured manner.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Biyazin, T., Fenta, B., Yetwale, A. et al. Patient-health care provider relationship during preoperative care in obstetric and gynecologic surgeries at Jimma Medical Center, Jimma, Ethiopia: patient’s perspective. Perioper Med 11, 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-022-00241-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-022-00241-8