Abstract

Background

Understanding the effects of gait speed on biomechanical variables is fundamental for a proper evaluation of alterations in gait, since pathological individuals tend to walk slower than healthy controls. Therefore, the aim of the study was to perform a systematic review of the effects of gait speed on spatiotemporal parameters, joint kinematics, joint kinetics, and ground reaction forces in healthy children, young adults, and older adults.

Methods

A systematic electronic search was performed on PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases to identify studies published between 1980 and 2019. A modified Quality Index was applied to assess methodological quality, and effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals were calculated as the standardized mean differences. For the meta-analyses, a fixed or random effect model and the statistical heterogeneity were calculated using the I2 index.

Results

Twenty original full-length studies were included in the final analyses with a total of 587 healthy individuals evaluated, of which four studies analyzed the gait pattern of 227 children, 16 studies of 310 young adults, and three studies of 59 older adults. In general, gait speed affected the amplitude of spatiotemporal gait parameters, joint kinematics, joint kinetics, and ground reaction forces with a decrease at slow speeds and increase at fast speeds in relation to the comfortable speed. Specifically, moderate-to-large effect sizes were found for each age group and speed: children (slow, − 3.61 to 0.59; fast, − 1.05 to 2.97), young adults (slow, − 3.56 to 4.06; fast, − 4.28 to 4.38), and older adults (slow, − 1.76 to 0.52; fast, − 0.29 to 1.43).

Conclusions

This review identified that speed affected the gait patterns of different populations with respect to the amplitude of spatiotemporal parameters, joint kinematics, joint kinetics, and ground reaction forces. Specifically, most of the values analyzed decreased at slower speeds and increased at faster speeds. Therefore, the effects of speed on gait patterns should also be considered when comparing the gait analysis of pathological individuals with normal or control ones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The quantification of the biomechanical characteristics of a person’s gait is an important clinical tool for evaluating normal and pathological patterns of locomotion [1, 2] and has been used in the decision process to prescribe treatment as well as to evaluate the intervention outcomes [3,4,5]. For example, the walking speed and not age has been considered the primary determinant of the kinematic and kinetic changes in children [6]. In fact, the speed at which a person walks influences biomechanical variables such as joint kinematics, ground reaction forces (GRF), joint moments of force (moments) and powers, muscle activity, and spatiotemporal gait parameters in children [6,7,8,9], young adults [10,11,12,13,14], and older adults [15, 16]. However, none of these studies considered all these variables together nor examined different age groups in the same study.

In a typical gait analysis, the gait patterns of pathological individuals are compared with a cohort of healthy individuals walking at their comfortable pace. However, as pathological individuals tend to walk slower and considering different age groups, without knowing which biomechanical variables are likely more affected by gait speed, this comparison may not be appropriate. Thus, to improve the knowledge about the effects of gait speed on biomechanical variables is paramount for benefitting clinicians who commonly rely on the outcomes of gait analysis to optimize patient care [17].

Although there are a handful of studies, including some reviews [18, 19] that examined the influence of walking speed on gait biomechanics, to our knowledge, no study has systematically reviewed the effects of speed on gait over a more comprehensive set of biomechanical variables and across different ages. For example, Telfer and collaborators [18] reported that walking speed has the largest effect on knee abduction moment in individuals over 18 years old, which is related to the development of the medial knee osteoarthritis [20]. Additionally, a systematic review by Herssens and collaborators [19] reported changes in the spatiotemporal parameters in healthy adults between 18 and 98 years old, but only at the self-selected walking speed.

Hence, the aim of the present study was to perform a systematic review of studies that have investigated the effects of gait speed on spatiotemporal parameters, joint kinematics, joint kinetics, and GRF variables in healthy individuals of various ages.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [21] (Additional file 1) and was registered in PROSPERO (ID122769). All studies were identified by three electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science) which comprise the most topics within the Biomedical and Health Sciences area [22]. The specific search strategy is described in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Selection criteria

The initial search was completed on December 2017, and on March 2019 a final search using the same terms was performed to verify potential newly published articles. Only original full-length studies published between 1980 and 2019 were included, with the specific inclusion criteria determined a priori: (1) walking as opposed to running; (2) normal (or equivalent), and slow and/or fast speeds measured quantitatively or qualitatively; (3) walking either on a ground or treadmill surface; (4) healthy participants with no orthopedic or neurological disease; (5) gait analysis on a level surface; (6) gait analysis using a three-dimensional (3D) motion capture system or 3D force platforms or both; and (7) article published in English. Reviews, conference papers, abstracts, letters, cases series, and pilot studies were excluded.

Inclusion criteria for the participants were healthy individuals with the age range based on the specific age group: children (4–17 years of age), young adults (18–59 years of age), and older adults (60–85 years of age). Studies that presented individuals with any musculoskeletal or neurological impairment were excluded. Since the aim of this systematic review was not to examine the effect of any intervention, only observational studies (e.g., cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional design) were included in this systematic review.

To ensure identification of all relevant studies, the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews were hand-searched [18, 19, 22].

Data extraction

All titles returned based on the search terms were first scanned by one of the co-authors, CAF. From the results of the original search, articles were excluded based on the inclusion criteria (e.g., animal study, non-English language, running task, etc.). Following this, all titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two reviewers, CAF and RKF (co-authors of this article), to determine their eligibility for the study. Whenever there was a disagreement between the two reviewers, the third author was consulted.

Characteristics of studies (authors, year), participants (sample size, age), surface types (treadmill or overground), and gait speed were extracted and reported in Table 1.

Methodological quality

All evaluated studies had their quality rated based on a modified version of the Quality Index (QI) tool originally described by Downs and Black [42]. From the original checklist, only item 27 was removed due to its ambiguity [43]. Twenty-six items, comprising the reporting and the external and internal (bias and confounding) validity assessment, were considered in the final analyses, with the maximum score being 27. The following cut-off adopted in this review was based on a previous study that also analyzed the gait kinetics, kinematics, and spatiotemporal parameters but during long-distance running [44]: high quality (≥ 80%), moderate (< 80% and ≥ 47%), and poor quality (< 40%).

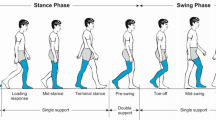

Variables of interest

The following variables were considered in the present study to address the research question: spatiotemporal gait parameters such as step length, stride length, stride time, and cadence; sagittal kinematic and kinetic variables such as hip, knee, and ankle joint angles and joint moments (when available); and horizontal and vertical GRF (for a general description of these variables see [45]). Since knee abduction moment (in the frontal plane) has been reported to be related to the incidence of knee injuries [46, 47], this variable was also analyzed. For consistency, all joint moments are reported as internal ones. For this review, we considered the global maximum and minimum values of the hip, knee, and ankle joint angles in the sagittal plane during the stance and swing phases of the gait cycle. For the joint moments, the maximum and minimum values in the sagittal plane and also the maximum and minimum values of the knee joint in the frontal plane were considered. For the GRF, the first and second peaks of vertical GRF (vertical1 and vertical2, respectively) and the braking and propulsive forces in the anterior-posterior direction were evaluated. Maximum and minimum values of the joint moments and GRF variables were analyzed only during the stance phase. All these variables were included because they have been reported in previous studies within the context of gait analysis [48, 49]. In this review, only studies that provided graphical or numerical data over the gait cycle were considered for further analysis. If a study was initially included in the final list but presented insufficient information, the authors were contacted and asked to provide the data. If they refused, were unable to, or did not respond to the requests, the study was removed from the list.

The effects of gait speed during walking were analyzed separately for children, young adults, and older adults. In cases where the study included sub-groups (i.e., 4–6 years, 6–8 years, 8–10 years), the results of these sub-groups were combined into one group according to the age groups examined in this review (children (4–17 years of age), young adults (18–59 years of age), and older adults (60–85 years of age)). Males and females were also combined. In this review, only the slow, comfortable, and fast speeds were considered for analysis. If any study presented more than three gait speeds (i.e., very slow, slow, comfortable, and fast), the very slow and slow speeds were combined. When the authors did not specify the speed for the comfortable condition, ranges from 1.07 to 1.32 m/s in children [6, 50], 1.05 to 1.43 m/s in young adults [50, 51], and 0.94 to 1.34 m/s in older adults [52] were adopted. Gait speeds below or above the range of each group were considered as slow and fast, respectively.

To account for the effect of gait speed, the effect size (ES) was calculated based on the ratio of the difference between group means of gait speeds and the pooled standard deviation. We compared the comfortable speed with the slow and fast speeds separately where the specific convention was adopted: for the comparison between slow and comfortable speed (slow < comfortable) and for the fast and comfortable speed (fast > comfortable). Additionally, when numerical data were not available but graphs were presented, we manually digitized the graph using the WebPlotDigitizer application (https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/) to obtain the values. The following guidelines were used to interpret the Cohen’s d ES [53, 54]: small (0.2–0.5), moderate (0.5–0.8), and large (> 0.8). To calculate the standardized effects across studies, a fixed- or random-effect model was applied based on the following criteria: if the heterogeneity is high (I2 > 50%), a random-model effect was chosen; contrarily, a fixed effect model was considered [55]. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to evaluate the heterogeneity of the standardized effects. The results for all variables are summarized as effect sizes, lower and upper CIs, standard errors (SEs), Cochran’s heterogeneity statistic (Q), I2 statistic, and p values for the children and older adult groups.

Results

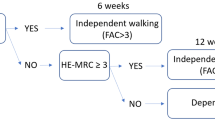

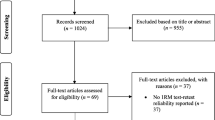

The search returned 19,791 articles that were first screened and considered for inclusion in the review. Based on the inclusion criteria, the full texts of 218 articles were then reviewed, and 18 studies were retained. Two additional studies were included because they were cited by the included studies and considered relevant for this review. Twenty studies were therefore used in the final analyses (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The methodological quality of the assessed studies was considered moderate, with a mean score of 15 (55%), ranging between 12 (44%) and 18 (67%) (Table 2). Overall, data from 587 healthy individuals were analyzed: 227 children (4 studies), 310 young adults (16 studies), and 59 older adults (3 studies), in both treadmill (6 studies) and overground (14 studies) surfaces with a range of walking speeds. The mean ages of the participants per group were children 10.3 years, young adults 27.1 years, and older adults 69.2 years. For consistency, when available, gait speeds were reported in units of meters per second. However, two studies reported speeds only in dimensionless units [7, 30] and the speeds in meters per second were found in other studies that analyzed the same subjects [12, 56].

Forest plots for the investigated gait parameters are presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. Due to the small number of studies of children and older adults, their results were presented as a table instead of a forest plot in the supplemental material (Additional file 3: Table S2, Additional file 4: Table S3, Additional file 5: Table S4, and Additional file 6: Table S5). Specific changes in gait pattern due to walking speed were reported separately for each age group.

Children

Gait speed influenced the spatiotemporal parameters in the child population. More specifically, large effects for cadence (ES = − 3.61, p < 0.001), step length (ES = − 3.29, p < 0.001), and stride length (ES = − 3.22, p < 0.001) were found during slower speeds, with a reduction in these variables when children walked slower. On the other hand, the stance duration (ES = 0.59, p < 0.001) presented a moderate effect, indicating an increase during slower speeds. At faster speeds, both cadence (ES = 2.97, p < 0.001) and step length (ES = 2.35, p < 0.001) presented large effect sizes, with higher values as the speed increased. Contrary to this, although there was also a large effect size for stance duration (ES = − 1.05, p < 0.001), its value decreased as the speed increased.

The joint kinematics showed large effect sizes for hip flexion (ES = − 0.80, p < 0.001), knee flexion (ES = − 1.34, p < 0.001), and ankle plantarflexion (ES = − 1.14, p < 0.001) angles, with decreases in their values as the speed decreased. There was a moderate effect for dorsiflexion angle (ES = 0.34, p = 0.031), but this increased at slower speeds. Regarding the fast speeds, a moderate effect was also found for ankle dorsiflexion angle (ES = − 0.63, p < 0.001), with a decrease in this at higher speeds.

For the joint kinetics, large effect sizes were found for the hip flexion (ES = − 1.70, p < 0.001) and knee extension (ES = − 1.52, p < 0.001) moments, and a moderate effect for the ankle plantarflexion moments (ES = − 0.60, p < 0.001). The results indicated that these variables decreased as walking speed decreased. In contrast, at faster speeds, the hip flexion, knee extension, and knee abduction moments increased as speed increased, with a moderate effect size for knee abduction (ES = 0.59, p < 0.001) and large effect sizes for hip flexion (ES = 1.84, p < 0.001) and knee extension (ES = 1.17, p = 0.024).

With regard to ground reaction forces, there were large effect sizes for the vertical1 (ES = − 1.21, p < 0.001), braking (ES = − 2.00, p < 0.001), and propulsive (ES = − 2.98, p < 0.001) forces, with lower values as the speed decreased. At faster speeds, these variables increased, with larger effect sizes for vertical1 (ES = 1.39, p < 0.001), braking (ES = 1.36, p < 0.001), and propulsive (ES = 1.50, p < 0.001) forces.

Young adults

At slower speeds, the gait parameters showed large effect sizes for cadence (ES = − 1.96, p < 0.001), step length (ES = − 1.53, p = 0.001), and stride length (ES = − 3.56, p = 0.009), indicating a decrease when individuals walked slower. At faster speeds, there were large effect sizes for both cadence (ES = 1.67, p < 0.001) and step length (ES = 0.83, p < 0.001), indicating increases in these variables as the speed increased (Fig. 2).

For the joint kinematics at slow speeds, the effect sizes were small for the hip flexion (ES = − 0.34, p = 0.028) and extension angles (ES = − 0.45, p = 0.004), moderate for the ankle plantarflexion angle (ES = − 0.54, p < 0.001) and large for the knee flexion angle (ES = − 0.90, p = 0.012), indicating decreases in these variables as the speed decreased. Regarding the faster speeds, small effect sizes were found for the hip flexion (ES = 0.41, p = 0.013) and ankle plantarflexion (ES = 0.32, p = 0.044) angles, indicating an increase in these variables with faster speeds (Fig. 4).

The joint kinetics showed large effect sizes for the hip flexion (ES = − 0.88, p = 0.003) and ankle plantarflexion moments (ES = − 1.37, p = 0.008), and a moderate effect size for the knee extension moment (ES = − 0.69, p = 0.018), indicating that these values decreased as the speed decreased. In contrast, at faster speeds, there were large effects for the hip flexion (ES = 1.82, p < 0.001), knee extension moments (ES = 1.27, p < 0.001), and ankle plantarflexion moments (ES = 1.03, p < 0.001) indicating higher values at faster speeds (Fig. 5).

For the ground reaction forces, there was a large effect size for vertical1 (ES = − 0.93, p = 0.017), indicating a decrease at slower speeds. At faster speeds, the propulsive force showed a moderate effect size (ES = 0.57, p = 0.019), indicating an increase as the speed increased (Fig. 6).

Older adults

For the older adult population, large effect sizes were found for the cadence (ES = − 1.86, p < 0.001), and step length (ES = − 1.14, p = 0.001) variables, indicating that both cadence and step length decreased when these individuals walked slower. When the individuals walked faster, there were large effect sizes for cadence (ES = 1.43, p < 0.001), step length (ES = 1.11, p = 0.001), and stride length (ES = 0.98, p < 0.001), indicating that these variables increased as the speed increased.

Regarding the joint angles and joint moments, significant effect sizes were found only at faster speeds. A moderate effect size was found for the hip flexion angle (ES = 0.57, p = 0.005), indicating an increase during faster speeds. For the joint moments, there were large effect sizes for both the hip flexion (ES = 1.01, p < 0.001) and knee extension (ES = 1.26, p < 0.001) moments, with these variables increasing as the speed increased.

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to analyze the effects of walking speed on gait spatiotemporal parameters, joint kinematics, joint kinetics, and ground reaction forces in children, young adults, and older adults. We compared these variables during walking at either slow or fast speeds with walking at comfortable speeds. In total, 20 studies were included in this review; most of the variables were significantly affected by gait speed, with moderate-to-large effect sizes. Overall, the investigated variables presented smaller absolute amplitudes of the minimum and maximum values at slower speeds and larger absolute amplitudes at faster speeds. However, the effects of speed on gait biomechanics were not similar across the three analyzed groups.

The spatiotemporal gait parameters were generally affected by walking speed in all three age groups, with large effect sizes. Cadence and stride length have been reported as key determinants of walking speed in human locomotion [57]. The results found in this study are in agreement with previous studies where they reported a decrease in the duration of the stance phase with increased walking speed in children [10, 24]. Additionally, as speed increased, step length in both young adults and older adults, and stride length in older adults, also increased, corroborating the findings of a previous study [10].

In general, differences in joint kinematics, joint kinetics, and ground reaction forces due to changes in gait speed showed moderate-to-large effect sizes. Previous studies have reported the walking speed dependencies for these variables [6, 7, 11, 12, 50, 58, 59]. More specifically, for the child population, we observed that fast walking speeds were related to increased values in knee joint moments, in agreement with previous studies [7, 59]. In young adults, the effects of gait speed on the minimum and maximum values of joint angles have also been reported, including increases in hip flexion, hip extension, knee flexion, and ankle plantarflexion angles with higher speeds [50, 58, 60,61,62]. Applying a prediction method, a study by Lelas et al. [12] reported that even though most parameters changed with increasing gait speed, the predictability was better for the kinetic parameters compared to kinematics. For the older adults, the kinematic and kinetic variables were affected to a lesser extent than in either young adults or children because the differences were observed only at fast speeds, while the ground reaction forces did not change in any speed comparisons. Specifically, increases in the hip and knee flexion moments were found when older adults walked faster, which has also been reported in a previous study [61]. The fact that the observed changes only occurred at faster speeds in this age group might be explained by the aging effects which slows gait, and therefore the impact on slow walking would be smaller [63]. Additionally, when compared with the young adults walking at similar speeds, the older adults were less affected by the gait speed, presenting less knee extension at heel-strike and lower knee flexion during the swing phase [64]. Regarding the differences in the GRF, this variable was also affected by the gait speed but only in the children’s and young adults’ groups. Comparing these two groups, changes were more pronounced in the children’s group, where the vertical1, braking, and propulsive forces decreased at slower speeds and increased at faster speeds. This pattern at faster speeds is in agreement with a previous study [24]. In young adults, only the vertical1 force decreased at slow speeds, while the propulsive force increased at fast speeds, as per the findings of previous studies [65, 66].

Comparing the different age groups, while in the child population, the gait pattern has not matured yet and the speed seems to affect it to a greater extent [59], in older adults, as the rate of decline in walking speed is typically about 0.7% per year [67], the gait pattern suggests to be less affected by the speed. Therefore, the gait speed should also be considered when studying the effects of age in children and older adults. Moreover, as the minimum and maximum values of these specific biomechanical variables have been used to compare the gait patterns of pathological individuals who tend to walk slower than the control group [5, 68, 69], this comparison may be doable only after collecting data from a number of individuals walking at a variety of gait speeds, which is time-consuming and expensive. Rather, the use of public gait datasets [70,71,72,73] when available or the use of prediction methods are more appropriate alternatives to enable the establishment of reference gait patterns at different walking speeds [12, 58, 60, 62, 74, 75]. In fact, when a prediction method was applied to predict the gait pattern adjusting for a difference in gait speeds between groups, it has reduced the impact of gait speed on the calculation of gait indices such as the Gait Profile Score in post-stroke individuals [76].

This systematic review included the search of only three electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science) and this may be considered a limitation. However, these databases were selected for search because of their broad inclusion of multidisciplinary topics within the Biomedical and Health Sciences domain and because they have been particularly adopted in gait research reviews [18, 22, 64, 77]. In addition, only studies that employed 3D gait analysis instrumentation were included in this review and meta-analysis, which resulted in the majority of included studies being observational in nature. Therefore, while we acknowledge the risk of publication bias, it solely was likely not as important as the overall quality of studies which was assessed through a Quality Index tool [42].

Conclusion

The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis show that speed affects the gait patterns of distinct age populations. Broader than previous reviews, where either only the knee moment or the spatiotemporal parameters was reported, this study analyzed the effects of speed on the gait pattern with respect to several gait parameters, including joint kinematics, kinetics, and ground reaction forces. In general, we observed that most of the absolute amplitude of the minimum and maximum values of the variables analyzed decreased at slower speeds and increased at faster speeds. The results of this study provide a stronger indication for the importance of also taking into account the effects of walking speed when comparing gait data of pathological individuals with normal or control individuals. Future studies involving such type of comparisons must control for the effects of different gait speeds, for example employing prediction methods in order to estimate the gait data of a normative group at the same speed of the pathological individual [75, 76].

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- ES:

-

Effect size

- GRF:

-

Ground reaction forces

- Q:

-

Cochran’s heterogeneity statistic

- QI:

-

Quality Index

- SEs:

-

Standard errors

References

Phinyomark A, Osis ST, Hettinga BA, Kobsar D, Ferber R. Gender differences in gait kinematics for patients with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:157.

Smith Y, Louw Q, Brink Y. The three-dimensional kinematics and spatiotemporal parameters of gait in 6–10 year old typically developed children in the cape metropole of South Africa – a pilot study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:200.

Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1990;8:383–92.

Simon SR. Quantification of human motion: gait analysis—benefits and limitations to its application to clinical problems. J Biomech. 2004;37:1869–80.

Naili JE, Wretenberg P, Lindgren V, Iversen MD, Hedström M, Broström EW. Improved knee biomechanics among patients reporting a good outcome in knee-related quality of life one year after total knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:122.

Stansfield BW, Hillman SJ, Hazlewood ME, Lawson AA, Mann AM, Loudon IR, et al. Normalized speed, not age, characterizes ground reaction force patterns in 5- to 12-year-old children walking at self-selected speeds. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:395–402.

Schwartz MH, Rozumalski A, Trost JP. The effect of walking speed on the gait of typically developing children. J Biomech. 2008;41:1639–50.

John CT, Seth A, Schwartz MH, Delp SL. Contributions of muscles to mediolateral ground reaction force over a range of walking speeds. J Biomech. 2012;45:2438–43.

Tirosh O, Sangeux M, Wong M, Thomason P, Graham HK. Walking speed effects on the lower limb electromyographic variability of healthy children aged 7-16 years. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2013;23:1451–9 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23886484. Accessed 27 Feb 2014.

Bovi G, Rabuffetti M, Mazzoleni P, Ferrarin M. A multiple-task gait analysis approach: kinematic, kinetic and EMG reference data for healthy young and adult subjects. Gait Posture. 2011;33:6–13.

Stoquart G, Detrembleur C, Lejeune T. Effect of speed on kinematic, kinetic, electromyographic and energetic reference values during treadmill walking. Neurophysiol Clin. 2008;38:105–16.

Lelas JL, Merriman GJ, Riley PO, Kerrigan DC. Predicting peak kinematic and kinetic parameters from gait speed. Gait Posture. 2003;17:106–12.

Murley GS, Menz HB, Landorf KB. Electromyographic patterns of tibialis posterior and related muscles when walking at different speeds. Gait Posture. 2014;39:1080–5.

Nymark JR, Balmer SJ, Melis EH, Lemaire ED, Millar S. Electromyographic and kinematic nondisabled gait differences at extremely slow overground and treadmill walking speeds. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42:523–34.

Lee HJ, Chang WH, Choi BO, Ryu GH, Kim YH. Age-related differences in muscle co-activation during locomotion and their relationship with gait speed: a pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:1–8.

Swinnen E, Baeyens J-P, Pintens S, Buyl R, Goossens M, Meeusen R, et al. Walking more slowly than with normal velocity: the influence on trunk and pelvis kinematics in young and older healthy persons. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2013;28:800–6.

Wren TAL, Gorton GE, Ounpuu S, Tucker CA. Efficacy of clinical gait analysis: a systematic review. Gait Posture. 2011;34:149–53.

Telfer S, Lange MJ, Sudduth ASM. Factors influencing knee adduction moment measurement: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Gait Posture. 2017;58:333–9.

Herssens N, Verbecque E, Hallemans A, Vereeck L, Van Rompaey V, Saeys W. Do spatiotemporal parameters and gait variability differ across the lifespan of healthy adults? A systematic review. Gait Posture. 2018;64:181–90.

Andriacchi TP. Dynamics of knee malalignment. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25:395–403.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;7:1006–12.

Roberts M, Mongeon D, Prince F. Biomechanical parameters for gait analysis: a systematic review of healthy human gait. Phys Ther Rehabil. 2017;4:6.

de David AC, Carpes FP, Stefanyshyn D. Effects of changing speed on knee and ankle joint load during walking and running. J Sports Sci. 2015;33:391–7.

Diop M, Rahmani A, Belli A, Gautheron V, Geyssant A, Cottalorda J. Influence of speed variation and age on ground reaction forces and stride parameters of children’s normal gait. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26:682–7.

Dubbeldam R, Buurke JH, Simons C, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Baan H, Nene AV, et al. The effects of walking speed on forefoot, hindfoot and ankle joint motion. Clin Biomech. 2010;25:796–801.

Giarmatzis G, Jonkers I, Wesseling M, Van Rossom S, Verschueren S. Loading of hip measured by hip contact forces at different speeds of walking and running. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30:1431–40.

Hsiao HY, Knarr BA, Higginson JS, Binder-Macleod SA. The relative contribution of ankle moment and trailing limb angle to propulsive force during gait. Hum Mov Sci. 2015;39:212–21.

Kerrigan D, Todd M, Croce U, et al. Biomechanical gait alterations independent on speed in the healthy elderly: evidence for specificLimiting Impairments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:317–22.

Khan SS, Khan SJ, Usman J. Effects of toe-out and toe-in gait with varying walking speeds on knee adduction moment and mechanical work done-a pilot study. IFMBE Proc. 2017;58:106–10.

Kwon JW, Son SM, Lee NK. Changes of kinematic parameters of lower extremities with gait speed: a 3D motion analysis study. J Phys Ther Sci. 2015;27:477–9.

Lewek MD. The influence of body weight support on ankle mechanics during treadmill walking. J Biomech. 2011;44:128–33.

van der Linden ML, Kerr AM, Hazlewood ME, Hillmann SJ, Robb JE. Kinematic and kinetic gait characteristics of normal children walking at a range of clinically relevant speed. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:800–6.

Monaco V, Rinaldi LA, Macrì G, Micera S. During walking elders increase efforts at proximal joints and keep low kinetics at the ankle. Clin Biomech. 2009;24:493–8.

Ridge ST, Henley J, Manal K, Miller F, Richards JG. Biomechanical analysis of gait termination in 11–17 year old youth at preferred and fast walking speeds. Hum Mov Sci. 2016;49:178–85.

Riley PO, Della Croce U, Casey Kerrigan D. Propulsive adaptation to changing gait speed. J Biomech. 2001;34:197–202.

Robbins SMK, Maly MR. The effect of gait speed on the knee adduction moment depends on waveform summary measures. Gait Posture. 2009;30:543–6.

Silder A, Heiderscheit B, Thelen DG. Active and passive contributions to joint kinetics during walking in older adults. J Biomech. 2008;41:1520–7.

Wang X, Ma Y, Hou BY, Lam WK. Influence of gait speeds on contact forces of lower limbs. J Healthc Eng. 2017;2017:6.

Weinhandl JT, Irmischer BS, Sievert ZA. Effects of gait speed of femoroacetabular joint forces. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2017;2017:7.

Winiarski S, Pietraszewska J, Pietraszewski B. Three-dimensional human gait pattern: reference data for young, active women walking with low, preferred, and high speeds. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–7.

Yang YT, Yoshida Y, Hortobágyi T, Suzuki S. Interaction between thorax, lumbar, and pelvis movements in the transverse plane during gait at three velocities. J Appl Biomech. 2013;29:261–9.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377-84.

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:iii-x.

Kyung H, Ali S, Fernandez J. Gait kinetics, kinematics, spatiotemporal and foot plantar pressure alteration in response to long-distance running: systematic review. Hum Mov Sci. 2018;57:342–56.

Baker R. Measuring walking. A handbook of clinical gait analysis. London: Mac Keith Press; 2013.

Myer GD, Ford KR, Di Stasi SL, Barber Foss KD, Micheli LJ, Hewett TE. High knee abduction moments are common risk factors for patellofemoral pain (PFP) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in girls: is PFP itself a predictor for subsequent ACL injury? Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:118–22.

Reeves ND, Bowling FL. Conservative biomechanical strategies for knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:113–22.

Lin PE, Sigward SM. Contributors to knee loading deficits during gait in individuals following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Gait Posture. 2018;66:83–7.

Johnston CD, Goodwin JS, Spang JT, Pietrosimone B, Blackburn JT. Gait biomechanics in individuals with patellar tendon and hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction grafts. J Biomech. 2018;82:103-8.

Öberg T, Karsznia A, Öberg K. Basic gait parameters: reference data for normal subjects, 10-79 years of age. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1993;30:210–23.

Al-Obaidi S, Wall JC, Al-Yaqoub A, Al-Ghanim M. Basic gait parameters: a comparison of reference data for normal subjects 20 to 29 years of age from Kuwait and Scandinavia. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40:361–6.

Bohannon RW, Williams Andrews A. Normal walking speed: a descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2011;97:182–9.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavorial sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum associates; 1988.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–9.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2003;327:557-60.

Liu MQ, Anderson FC, Schwartz MH, Delp SL. Muscle contributions to support and progression over a range of walking speeds. J Biomech. 2008;41:3243–52.

Murray MP, Kory RC, Clarkson BH, Sepic SB. Comparison of free and fast speed walking patterns of normal men. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1966;45:8–23.

Kirtley C, Whittle MW, Jefferson RJ. Influence of walking speed on gait parameters. J Biomed Eng. 1985;7:282–8.

Van Hamme A, El Habachi A, Samson W, Dumas R, Chèze L, Dohin B. Gait parameters database for young children: the influences of age and walking speed. Clin Biomech. 2015;30:572–7.

Koopman B, van Asseldonk EHF, van der Kooij H. Speed-dependent reference joint trajectory generation for robotic gait support. J Biomech. 2014;47:1447-58.

Kerrigan D, Todd M, Croce U, et al. Biomechanical gait alternations independent on speed in the healthy elderly: Evidence for specificLimiting Impairments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:317–22.

Hanlon M, Anderson R. Prediction methods to account for the effect of gait speed on lower limb angular kinematics. Gait Posture. 2006;24:280–7.

Nutt JG. Classification of gait and balance disorders. Adv Neurol. 2001;87:135–41.

Boyer KA, Johnson RT, Banks JJ, Jewell C, Hafer JF. Systematic review and meta-analysis of gait mechanics in young and older adults. Exp Gerontol. 2017;95:63–70.

Nilsson J, Thorstensson A. Ground reaction forces at different speeds of human walking and running. Acta Physiol Scand. 1989;136:217–27.

Peterson CL, Kautz SA, Neptune RR. Braking and propulsive impulses increase with speed during accelerated and decelerated walking. Gait Posture. 2011;33:562–7.

Bendall M, Bassey E, Pearson M. Factors affecting walking speed of elderly people. Age Ageing. 1989;18:327–32.

Hsiao H, Knarr BA, Pohlig RT, Higginson JS, Binder-Macleod SA. Mechanisms used to increase peak propulsive force following 12-weeks of gait training in individuals poststroke. J Biomech. 2016;49:388–95.

Eitzen I, Fernandes L, Nordsletten L, Risberg MA. Sagittal plane gait characteristics in hip osteoarthritis patients with mild to moderate symptoms compared to healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:258.

Fukuchi CA, Fukuchi RK, Duarte M. A public dataset of overground and treadmill walking kinematics and kinetics in healthy individuals. PeerJ. 2018;6:e4640.

Moore JK, Hnat SK, van den Bogert AJ. An elaborate data set on human gait and the effect of mechanical perturbations. PeerJ. 2015;3:e918.

Wang Y, Srinivasan M. Stepping in the direction of the fall: the next foot placement can be predicted from current upper body state in steady-state walking. Biol Lett. 2014;10:3–7.

van den Bogert AJ, Geijtenbeek T, Even-Zohar O, Steenbrink F, Hardin EC. A real-time system for biomechanical analysis of human movement and muscle function. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2013;51:1069–77.

Stansfield BW, Hillman SJ, Hazlewood ME, Robb JE. Regression analysis of gait parameters with speed in normal children walking at self-selected speeds. Gait Posture. 2006;23:288–94.

Fukuchi CA, Duarte M. A prediction method of speed-dependent walking patterns for healthy individuals. Gait Posture. 2018;68:280–4.

Fukuchi CA, Duarte M. Gait Profile Score in able-bodied and post-stroke individuals adjusted for the effect of gait speed. Gait Posture. 2019;69:40–5.

Mousavi SH, Hijmans JM, Rajabi R, Diercks R, Zwerver J, van der Worp H. Kinematic risk factors for lower limb tendinopathy in distance runners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture. 2019;69:13–24.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil (#2014/13502-7, #2015/14810-0 and #2019/06604-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CAF and MD conceived and designed the study protocol. CAF and RKF screened all the references, extracted the data, and wrote the paper. MD served as arbitrator in case of discrepancies during extraction and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA 2009 Checklist. (PDF 89 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Search strategy. (PDF 9 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Meta-analysis for the comparison between slow × comfortable speeds for the children. (PDF 82 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S3. Meta-analysis for the comparison between comfortable × fast speeds for the children. (PDF 75 kb)

Additional file 5:

Table S4. Meta-analysis for the comparison between slow × comfortable speeds for the older adults. (PDF 71 kb)

Additional file 6:

Table S5. Meta-analysis for the comparison between comfortable × fast speeds for the older adults. (PDF 71 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukuchi, C.A., Fukuchi, R.K. & Duarte, M. Effects of walking speed on gait biomechanics in healthy participants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 8, 153 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1063-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1063-z