Abstract

Key message

In arboriculture, the number and diversity of pollen donors can have a major impact on fruit production. We studied pollination insurance in hybrid chestnut orchards (C. sativa × C. crenata) provided by nearby wild European chestnuts (C. sativa) in southwestern France. Most fruits were sired by hybrid pollenizers rather than by wild chestnuts. When these hybrid pollenizers were too scarce, a frequent situation, pollen produced by wild chestnut trees did not compensate for the lack of compatible pollen and fertilization rates and fruit production collapsed.

Context

The demand for chestnuts has been increasing in recent years in many European countries, but fruit production is not sufficient to meet this demand. Improving pollination service in chestnut orchards could increase fruit production.

Aims

Investigate pollination service in chestnut orchards. Evaluate the contribution to pollination of trees growing in chestnut woods and forests.

Methods

We investigated five orchards planted with hybrid chestnuts (C. sativa × C. crenata) cultivars in southwestern France. We combined fruit set data, which provide information about pollination rate, with genetic data, which provide information about pollen origin. We used this information to estimate the contribution of nearby C. sativa forest stands to the pollination of each orchard.

Results

Pollination rates vary considerably, being fivefold higher in orchards comprising numerous pollen donors than in monovarietal orchards. Because of asymmetric hybridization barriers between hybrid and purebred cultivars, the surrounding chestnut forests provide very limited pollination insurance: less than 14% of the flowers in these monovarietal orchards had been pollinated by forest trees.

Conclusion

Because chestnut orchards are now increasingly relying on hybrid cultivars, surrounding wild European chestnut trees are no longer a reliable pollen source. To achieve maximal fruit set, efforts must therefore concentrate on orchard design, which should include enough cultivar diversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fruit production depends on effective pollination services (Reilly et al. 2020). For entomophilous plants, fruit production is negatively affected if pollinators are rare or ineffective (pollinator limitation) and if the quantity and quality of pollen produced are insufficient (pollenizer limitation) (Wilcock and Neiland 2002). For native cultivated plant species, two distinct pollination services must therefore be considered: the service provided by wild pollinators and the service provided by wild pollenizers, both of which determine to fruit production. The most straightforward way to study pollenizer limitation is to use paternity analyses to determine pollen origin. Combining these paternity analyses with fruit set measurements should result in an integrated view of pollination.

In arboriculture, the effect of pollenizer cultivar diversity on orchard yield is an important issue. To investigate this question, experiments involving manual application of pollen to flowers have been used (e.g., Kron and Husband 2006; Carisio et al. 2020). However, these approaches are time-consuming and do not provide information on the identity of pollen donors. Paternity analysis represents a promising alternative. Researchers increasingly use this method to explore the functioning of orchards. Recent studies have focused on chestnut (Nishio et al. 2019), avocado (Ying et al. 2009), clementine (Pons et al. 2011), crab-apple (Feurtey et al. 2017), mango (Pérez et al. 2016), olive (Mookerjee et al. 2005; Pinillos and Cuevas 2009; Shemer et al. 2014; Biton et al. 2020; Mariotti et al. 2021; Vuletin Selak et al. 2021), plum (Meland et al. 2020), and sweet cherry (Guajardo et al. 2017). For instance, in olive, one of the most studied species, Mookerjee et al. (2005) highlighted pollen exchanges between different cultivars and identified those with the highest male fecundity. In avocado, Ying et al. (2009) estimated the importance of self-pollination. In apple, Feurtey et al. (2017) estimated crop-to-wild gene flow. In chestnut, Nishio et al. (2019) studied the relationship between fruit production and distance between mother and pollen donor trees.

However, all these paternity analyses share the same limitations. First, it is generally impossible to genotype all potential fathers. Consequently, only offspring whose father can be unambiguously identified are informative. This reduces the power of the analyses and can create some biases. A solution would be to obtain additional information on pollen origin, for example by taking advantage of the genetic structure of the studied population. A second limitation of these paternity analyses is that we can study only successful pollination events, not failed pollination events. Yet, in arboriculture, a major objective is to understand the causes of pollination failures, such as lack of pollen or poor quality of pollen received by stigmas. A solution to circumvent this problem would be to combine paternity analyses with fruit set studies.

Chestnut is a suitable model for exploring these issues. First, fruit set can easily be estimated in the fall in this species, by taking advantage of the structure of the infrutescences (the burrs). In each burr, filled fruits correspond to successfully pollinated flowers and empty fruits correspond to flowers that have not received compatible pollen (e.g., Larue et al. 2021a, 2022). Second, in Europe, different chestnut gene pools corresponding to different species and hybrids are often present in the orchards and in the surrounding landscape, so that even if the father cannot be identified using paternity analyses, its taxonomic identity can be inferred using the existing genetic structure. In France and in much of southern Europe, chestnut cultivation has experienced its golden age in the early nineteenth century but has declined considerably since that time, due in particular to two diseases originating from Asia, ink disease and bark canker (Pitte 1986). To identify tolerant chestnut genotypes, interspecific crosses between the European chestnut and either the Japanese chestnut (C. crenata) or the Chinese chestnut (C. mollissima) have been performed. Among the offspring, interspecific cultivars tolerant to ink disease have been selected (Gonthier and Robin 2019; Larue et al. 2021b). In southwestern France, orchards are now mostly composed of a small number of hybrid cultivars between European and Japanese chestnuts. In particular, two hybrid cultivars have been massively planted for fruit production: “Marigoule,” a C. crenata × C. sativa hybrid, and “Bouche de Bétizac,” a C. sativa × C. crenata hybrid. Both are grafted on either “Marsol” or “Maraval,” two C. crenata × C. sativa hybrid ink-resistant rootstocks (Breisch 1995). However, hybridization barriers exist between the different chestnut species (Larue et al. 2022). On Eurojapanese hybrid mother trees, Japanese chestnut pollen is strongly favored: it is five times more competitive than hybrid pollen. Instead, European chestnut pollen is disadvantaged: it is two times less competitive than hybrid pollen (Larue et al. 2022). In principle, European chestnut trees present in the neighboring landscape, whether of cultivated origin or growing naturally in nearby forests and woods, could provide a form of pollination insurance for orchards planted with too few or incompatible pollen-donor cultivars. However, since pollen from a European chestnut arriving on a female flower of a hybrid chestnut is disadvantaged, the expected pollination service of these wild trees is unclear.

Contrary to what was originally thought, chestnuts are not wind-pollinated: instead, they are entirely dependent on wild insects for their pollination (Larue et al. 2021a; Petit and Larue 2022). Moreover, they are self-incompatible (Stout 1926; Xiong et al. 2019). Hence, orchards should include several compatible pollenizer cultivars (Breisch 1995), accounting for the fact that not all cultivars produce pollen (Fig. 1). Astaminate cultivars lack stamens, brachystaminate cultivars have stamens shorter than the perianth, mesostaminate cultivars have stamens as long as the perianth, and longistaminate cultivars have stamens longer than the perianth (Soylu 1992). Only longistaminate cultivars and to a lesser extent mesostaminate cultivars produce pollen, whereas astaminate and brachystaminate cultivars can be considered as entirely or nearly entirely male-sterile, as shown recently using paternity analyses (Larue et al. 2022).

Male flowers of chestnut trees. A Male catkin of a male-sterile tree (astaminate variety): flowers are open, but most stamens are aborted and do not produce pollen. B Male catkin of a male-fertile tree (longistaminate variety): stamens are present and are protruding; they produce abundant fertile pollen

Here, we propose an original method combining fruit set studies along with genetic structure analyses and paternity analyses to investigate pollination success in five production orchards made up of a maximum of two fruit-producing hybrid chestnut cultivars, a male-fertile and a male-sterile one. These five orchards differ markedly in cultivar diversity and in the presence or absence of neighboring chestnut forest trees. We aim to (1) check if fruit set increases when the number of potential pollen donors planted in the orchard increases, (2) identify pollen sources, and (3) quantify the role of orchard cultivar diversity and of the presence of nearby chestnut forests for fruit set.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study sites

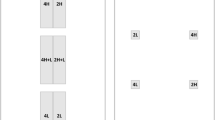

To test the effects of orchard cultivar diversity on fruit set (i.e., the percentage of female flowers giving a fruit), we selected five production orchards in the southwest of Dordogne, in southwestern France (Fig. 2). The first orchard (A), with an area of 1.4 ha, is composed of a single chestnut cultivar, “Marigoule,” and is isolated: no chestnut forest is present within a radius of 5 km (Table 1). According to the owner, there is no pollenizer planted in the orchard (Fig. 3, top, left). The second orchard (B) is composed of two plots with a total area of 9.2 ha (Table 1). A chestnut forest surrounds these two plots (Fig. 3, top, right). According to the owner, all trees belong to “Marigoule” cultivar, except for two unidentified chestnut trees. The third orchard (C) is composed of two cultivars grown for fruit production, “Marigoule” and “Bouche de Bétizac,” and covers 8.3 ha (Table 1). This orchard is isolated (Fig. 3, middle, left). According to the owner, there are 13 different genotypes used as pollen donors. However, they are quite small because they were planted after the trees used for fruit production and are represented by only a few ramets. Some of these pollenizers are common Eurojapanese hybrid cultivars (C. sativa × C. crenata or the reciprocal cross) described in Breisch (1995), while others originate from crosses between C. mollissima and C. crenata. The fourth orchard (D) covers 6.0 ha and is located in a chestnut forest (Table 1). The cultivars used for fruit production are “Marigoule” and “Bouche de Bétizac.” Several pollenizers are present, mostly common Eurojapanese hybrid cultivars (Fig. 3, middle, right). The last orchard (E) is a plot of the experimental orchards of Invenio, a Research and Experimental station on fruit trees and vegetables located near Douville (Dordogne). Invenio experimental orchards cover 18 ha but the studied plot measures only 0.8 ha (Table 1). It is composed of “Marigoule” and “Bouche de Bétizac” cultivars and includes numerous potential pollenizer trees belonging to C. sativa, C. crenata, C. mollissima, and their hybrids. Moreover, a chestnut forest borders the orchard to the east (Fig. 3, bottom, left).

Aerial photographs of the five studied orchards. Orchard A is isolated. All trees belong to “Marigoule” cultivar. In Orchard B almost all trees are “Marigoule” cultivar. This orchard is surrounded by a chestnut forest. Orchard C is isolated almost all trees are “Marigoule” and “Bouche de Bétizac” cultivars and pollinizer are rare and small in size. Orchard D is located in a chestnut forest. Majority of trees are “Marigoule” and “Bouche de Bétizac” cultivars but numerous pollinizers are planted inside the orchard. Orchard E is one of the plots of Invenio experimental station which includes numerous genotypes from the three chestnut species and their hybrids. Studied plot is the most eastern plot (blue) and is adjacent to a chestnut forest. On each photograph, the scale (1:5000) is provided in the bottom left (each black or white bar corresponds to 100 m)

2.2 Fruit set estimation

Female inflorescences of chestnuts are typically composed of three female flowers located side by side. The inflorescence develops into an infrutescence called a burr. In each burr, each of the three female flowers, if pollinated, develops into a nut (i.e., a fruit generally consisting of a single seed contained in a pericarp of maternal origin). If the flower is not pollinated, an empty fruit is produced, i.e., only the pericarp is present (Larue 2021; Larue and Petit 2022). To estimate pollination success of the trees investigated, we did not follow the fate of individual female flowers, a time-consuming approach, but used instead simple measures of fruit set performed in late summer. These measures have long been used to estimate pollination service in chestnut orchards (Manino et al. 1991; de Oliveira et al. 2001; reviewed in Larue et al. 2021a). However, mechanisms unrelated to pollination success can affect the proportion of empty burrs. To correct for the bias resulting from excess or deficit of empty burrs, for instance caused by premature abortion of empty burrs in summer, we adjusted a binomial zero-truncated distribution to the distribution of burrs with one, two, or three developed fruits for each tree. We showed previously that this procedure results in a more accurate estimation of pollination success than that relying on all burrs, including empty ones (Larue 2021; Larue et al. 2022; Larue and Petit 2022). In fall 2019, we selected 45 trees in the five studied orchards. These trees were randomly selected, except in orchard E, in which trees from the two cultivars are distributed in alternating rows. In particular, “Bouche de Bétizac” trees were sampled in a single row, next to the forest (Table 2). On all trees, we randomly selected between 30 and 60 burrs. For each burr, we counted developed and empty fruits. We aimed to include a minimum of 20 burrs with at least one developed fruit, but this threshold was not always reached in poorly pollinated orchards.

2.3 Plant material for DNA analyses

For genotyping, we randomly selected 10 developed fruits per tree, except in Douville where we selected more material: 20 fruits each “Bouche de Bétizac” ramet and 22–23 fruits for each “Marigoule” ramet (Table 2). We also sampled one leaf on each mother tree and one leaf on all distinct cultivars found in the orchard. Fruits and leaves were stored at 2 °C until DNA isolation.

2.4 DNA isolation and genotyping

We isolated DNA from 50 mg of tissue using CTAB custom DNA isolation protocol for 96-well plate format with 2.4 M NaCl lysis buffer for fruits and 1.4 M NaCl lysis buffer for leaves (Larue et al. 2021d). We checked the quality of the DNA with a spectrophotometer Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 8000. We characterized each sample at 79 SNP using Agena MassARRAY Platform (Larue et al. 2021d) and checked the raw data using MassARRAY Typer Analyzer 4.0.26.75 (Agena Biosciences) to exclude loci with weak signal (i.e., too many missing values) or ambiguous signal (i.e., unclear cluster delimitation). We then searched for null alleles using MISMATCHFINDER (Larue et al. 2021d). We finally retained 65 SNP to perform the subsequent analyses.

2.5 Genetic structure and paternity analyses

We identified all samples having the same multilocus genotype using “Multilocus Matches” function from GENALEX 6.503 (Peakall and Smouse 2012) and carefully inspected the results manually. We kept only one copy of each genotype for the remaining analyses. We used the Bayesian clustering analysis software STRUCTURE (Pritchard et al. 2000) to assign each genet to a species (Fernández‐López et al. 2021; Larue 2021). Chestnut species are defined using reference genotypes of C. mollissima, C. crenata, and C. sativa from the INRAE chestnut genetic collection of Bordeaux (Larue et al. 2021b, Appendix 6.1: a). We then assigned all samples from the five production orchards (adult trees and seeds) to the three chestnut species and their hybrids (Appendix 6.1: b). We had developed the molecular markers with the goal to differentiate the different species of chestnuts and their hybrids (Larue et al. 2021d). Therefore, variation of admixture coefficients across runs was very small (results not shown), and we kept only six iterations for the STRUCTURE analyses.

Purebred individuals have expected admixture levels of 0 and 1, F1 hybrids of 0.5, and backcrosses of 0.25 and 0.75, so midpoint values of 0.125 and 0.875 are considered optimal to distinguish between purebreds and backcrosses, and midpoint values of 0.375 and 0.625 to distinguish between hybrids and backcrosses (Guichoux et al. 2013). We distinguished three types of seeds, noting that all seeds studied are necessarily the offspring of Eurojapanese hybrid mother trees (i.e., mothers with expected C. sativa and C. crenata ancestries of 0.5). The first group is made of seeds with a C. mollissima paternal contribution. If the father is a pure C. mollissima, the seed will have an admixture value of 0.5 for C. mollissima. If the father is a F1 hybrid involving C. mollissima, the seed will have an admixture value of 0.25 for C. mollissima. To distinguish between seeds sired by C. mollissima purebreds or hybrids (expected admixture values for the C. mollissima gene pool > 0.25) and seeds sired by trees that do not have C. mollissima ancestry (expected admixture value of 0.0), the optimal threshold is 0.125. For this first group, characterized by a C. mollissima ancestry > 0.125, we did not attempt to perform paternity analyses to identify the cultivar of the pollen donor due to limited power.

The second group corresponds to seeds with a C. sativa father, i.e., to backcrosses with an expected C. sativa ancestry of 0.75. If the father is a C. sativa × C. crenata hybrid, the seed (an F2) will have a C. sativa ancestry of 0.5. The optimal threshold to distinguish between seeds sired by pure C. sativa (first-generation backcross) and those sired by F1 hybrids (F2) is a C. sativa ancestry of 0.625. This second group therefore consists of all seeds with a C. sativa ancestry > 0.625 and a C. mollissima ancestry < 0.125.

The third group includes all remaining seeds sired either by a C. crenata purebred (expected ancestry of 0.75 for C. crenata and 0.25 for C. sativa) or by a C. sativa × C. crenata hybrid (expected ancestry of 0.5 for C. crenata and 0.5 for C. sativa). This third group therefore consists of all seeds with a C. sativa ancestry < 0.625 and a C. mollissima ancestry < 0.125.

For paternity analyses, we included as candidate fathers all adult genotypes identified in the five orchards as well as a list of genotypes of traditional and modern chestnut cultivars known to be widely cultivated in the region. We performed two categorical paternity analyses using the software CERVUS (Kalinowski et al. 2007). The first was for seeds presumed to have been sired by C. sativa and the second for seeds presumed to have been sired by a tree with some C. crenata background. For the first paternity analysis, we used as background frequencies the allelic frequencies of the unique genotypes of C. sativa. We list the parameters used for genotype simulation in Appendix 6.2: a. We did not allow selfing in the simulations as we were looking for crosses between hybrid mother trees and pure C. sativa. For the second paternity analysis, we calculated allelic frequencies using the unique genotypes of C. crenata and of Eurojapanese hybrids. We provide parameters for genotype simulation in Appendix 6.2: b. Mother trees are Eurojapanese hybrids and the father can be a Eurojapanese hybrid so we allowed self-fertilization. We calculated confidence intervals using LOD and delta LOD with a relaxed level of 95% and a strict level of 99%.

2.6 GIS analyses

We performed all spatial analyses with QGIS software (QGIS Development Team 2022). Satellite photographs used for map background come from IGN BD ORTHO. Georeferencing system used in these analyses is Lambert 93.

2.7 Statistical analyses

We performed all statistical analyses with R software (v3.6.6; R Core Team 2013). We calculated the corrected fruit set with basic functions implemented in R and produced the illustrations with the ggplot2 (v3,6,3; Wickham 2016), ggthemes (v4.2.4; Arnold 2016), and cowplot (v1.1.1; Wilke 2020) packages.

3 Results

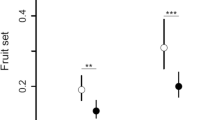

3.1 Fruit set

Fruit set data are provided in Larue (2022). For “Bouche de Bétizac” trees, fruit set was 63% in orchard C, 84% in orchard D, and 95% in orchard E (Fig. 4). For “Marigoule” trees, fruit set was 11% in orchard A, 21% in orchard B, 21% in orchard C, 39% in orchard D, and 48% in orchard E (Fig. 4). Fruit sets of the two cultivars in the same orchard greatly differed. Average fruit set of “Bouche de Bétizac” was 80% compared to only 38% for Marigoule. The difference between the two cultivars was particularly marked in the less well-pollinated orchard (C).

3.2 Genotyping success and genetic data curation

Genotyping results show that all sampled adult trees belong to the expected cultivar, “Marigoule” or “Bouche de Bétizac.” We assigned the genotyped adult trees to the different chestnut species and hybrids with the software STRUCTURE. We successfully genotyped 547 of the 601 fruits collected (91%) at more than 33 SNPs, allowing an even representation of all orchards and providing enough genetic power for our objectives (Table 2).

3.3 Structure analyses

We assigned the father of the 547 genotyped seeds to the three categories (C. mollissima or its hybrids, C. sativa, and C. crenata or Eurojapanese hybrids) using the thresholds described in the “Material and methods” section (Table 3). All corresponding data are provided in Larue (2022). A total of 284 seeds had been sired by a C. crenata tree or by a hybrid tree involving C. crenata (52%), 204 by a C. sativa tree (40%) and 59 by a C. mollissima (or hybrid C. mollissima) tree (8%). For the “Marigoule” cultivar in orchards A and B, the large majority of fruits had a C. sativa father: 73% in orchard A and 74% in orchard B. In the other three orchards, the majority of “Marigoule” fruits had a C. crenata or a Eurojapanese hybrid father: 41% in orchard C, 51% in orchard D, and 49% in orchard E. For the “Bouche de Bétizac” cultivar, most fruits had a C. crenata or a Eurojapanese hybrid father: 86% in orchards C and D and 61% in orchard E. Very few seeds had a father with C. mollissima ancestry: less than 2% for “Bouche de Bétizac” offspring and less than 4% for “Marigoule” offspring. The only exception was for orchards C and E planted with some C. mollissima trees. However, even in these orchards, the proportion of seeds with C. mollissima ancestry remained small.

3.4 Paternity analyses

All files used for these analyses are from Larue (2022), and we provide details of paternity analysis for seeds sired by C. sativa trees and for seeds sired by C. crenata or by Eurojapanese trees in Appendices 6.3 and 6.4. We identified the father for only 6% (13 out of 204) of the seeds sired by C. sativa and for as much as 93% (263 out of 284) of the seeds sired by C. crenata or by Eurojapanese hybrids (Tables 4 and 5). This means that the C. sativa fathers generally do not match with cultivars used as reference, even though we included all widely cultivated cultivars in the region (Table 4). For seeds sired by C. crenata or by Eurojapanese hybrids, we could distinguish two cases. In orchards that include several pollen donors, namely orchard C (for “Bouche de Bétizac”), orchard D, and orchard E, most identified fathers originate from the orchard (Table 5). In poorly pollinated orchards, i.e., orchards A, B, and C (for “Marigoule”), the few identified fathers were either generally “Marigoule” itself (selfed seeds) or rootstock cultivars (Table 5).

When “Bouche de Bétizac” and “Marigoule” cultivars co-occur in an orchard, their mutual siring success was very contrasted: “Bouche de Bétizac,” a brachystaminate cultivar, sired only two fruits on “Marigoule,” i.e., < 1% of the genotyped seeds, while “Marigoule,” a longistaminate cultivar, sired 66 fruits on “Bouche de Bétizac,” i.e., 50% of the genotyped seeds (Table 5).

Self-pollinated seeds were more frequent on “Marigoule” than on “Bouche de Bétizac”: 11 of the 145 seeds collected on “Marigoule” were self-pollinated (i.e., 8%) while only two of the 132 seeds collected on “Bouche de Bétizac” were self-pollinated (i.e., 2%) (Table 5). Self-pollinated seeds of “Marigoule” were mostly present in orchards A, B, and C, the poorly pollinated orchards.

The two cultivars usually used as rootstocks, “Marsol” and “Maraval,” sired 55 of the 263 genotyped seeds, i.e., 21% of the total (Table 5). Whether they had been planted voluntarily as pollen donors (in orchards D and E), or whether they developed following graft failure, as must have happened in orchards A, B, and C, they turned out to be efficient pollenizers. In poorly pollinated orchards, they increased pollen donor diversity and sired relatively many fruits: for “Marigoule,” 14% in orchard A, 20% in orchard B, and 27% in orchard C. For “Bouche de Bétizac” in orchard C, these two cultivars sired 24% of the genotyped seeds (Table 5).

3.5 Pollination success

By coupling fruit set estimates, which provide information on fertilization probability, and genetic analyses, which provide information about the identity of the trees that pollinate the female flowers, a more complete understanding of pollination services can be achieved (Fig. 5). Female flowers aborted at very different rates in the two cultivars: abortion rate ranged from 48 to 90% in “Marigoule” and from 5 to 33% in “Bouche de Bétizac.” This abortion rate was particularly high for fruits of “Marigoule” in orchards A, B, and C (respectively 90, 80, and 67%). In these three orchards, few suitable pollenizers were present for “Marigoule” mothers. In particular, C. crenata or Eurojapanese pollenizer trees were nearly completely absent and sired very few seeds (only 1% in orchards A and B, and 8% in orchard C). This proportion was much higher in the two other orchards (19% in orchard D and 22% in orchard E) (Table 6). For the “Bouche de Bétizac” cultivar, most female flowers were fertilized by C. crenata or by Eurojapanese hybrid trees planted in the orchard: 52% in orchard C, 69% in orchard D, and 54% in orchard E (Table 6). For both “Bouche de Bétizac” and “Marigoule” cultivars, C. sativa trees sired only a small fraction of the female flowers (7–35%), even in the absence of other types of pollenizers, and most of the corresponding pollen donors did not belong to any traditional C. sativa cultivar (Table 4).

4 Discussion

The approach used, combining fruit set measurements, genetic assignment, and paternity analyses, allowed a detailed study of orchard pollination. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that genetic analyses are combined with fruit set measurements to investigate fruit tree production. Our study, although based on a few (but contrasted) orchards, resulted in a detailed understanding of the factors that limit fruit production. In particular, we could show that cultivar diversity has a major impact on fruit production: orchards with numerous pollenizers had a fivefold higher fruit set compared with monovarietal orchards.

Fruit set of “Bouche de Bétizac,” a male-sterile cultivar, was much higher than that of “Marigoule,” a male-fertile cultivar, confirming earlier results showing that male sterility greatly increases fruit set (Larue et al. 2022). Male-fertile trees produce large amounts of pollen. Due to late-acting self-incompatibility, this abundant pollen results in female flower abortion caused by ovule degeneration following penetration by self-pollen tubes (Barrett et al. 1996). Male-sterile trees have therefore a strong advantage, resulting in much higher fruit sets (Larue et al. 2022; Larue and Petit 2022). Interestingly, in Europe, a substantial number of modern and traditional cultivars are male-sterile (Pereira-Lorenzo et al. 2006; Furones-Pérez and Fernández-López 2009; Martín et al. 2017). As shown here, these so-called male-sterile cultivars do sire a few fruits and are therefore not totally male-sterile, confirming earlier results obtained in a previous large-scale paternity analysis (Larue et al. 2022). This finding of partial fertility of male-sterile cultivars is in line with the current understanding of the nature of male sterility in fruit trees (Xu et al. 2022).

In the three orchards where male-sterile and male-fertile cultivars co-occur, the male-fertile cultivar pollinated most of the fruits of the male-sterile cultivar. In contrast, the male-sterile cultivar pollinated only a few seeds of the male-fertile cultivar, resulting in highly asymmetric pollen exchange and fruit sets. In orchard C, “Marigoule” trees experienced a very high abortion rate (67%) despite the presence of several hybrid pollenizers. However, these pollen donors had been planted several years after the establishment of the orchard. Therefore, they still produce limited amounts of pollen, resulting in reduced pollination service. This shows that, to ensure high fruit set in chestnut orchards, it is preferable to introduce from the outset several pollen donors.

C. sativa chestnut forests were present in the vicinity of three of the five studied orchards (orchards B, D, and E). Pollination insurance conferred by these trees was rather low: there were 14% of female flowers pollinated by pollen of C. sativa in orchard B, 15% in orchard D, and 23% in orchard E, despite the large number of wild chestnut trees present in the vicinity. In orchard E, C. sativa pollen sired nearly 32% of the fruits harvested on “Bouche de Bétizac” trees, while in orchards C and D, it sired less than 10% of the fruits. We think that this difference is caused by the configuration of the plots: in orchard E, all trees had been sampled in a single row bordering the forest. In the two other orchards, studied trees are located throughout the orchard and are therefore typically distant from nearby chestnut woods by several tens of meters.

We explain the low pollination insurance provided by forest trees by the existence of interspecific barriers (Larue et al. 2022). When the mother tree is a Eurojapanese hybrid, C. sativa or C. mollissima pollen are counter-selected compared to pollen from hybrid trees (Larue et al. 2022). In addition, C. sativa cultivars and forest trees bloom several days later than Eurojapanese chestnut trees (Larue et al. 2021c). Thus, despite their abundance, C. sativa trees from nearby forests do not sire many fruits on hybrid cultivars. In contrast, the few hybrids planted in orchards sire the majority of the fruits.

Since chestnut production in southwestern France is mostly based on interspecific chestnut hybrid cultivars (Breisch 1995), pollination insurance provided by populations of local spontaneous European chestnuts is low. In principle, in the future, the ecosystem service provided by wild pollinators could also decrease if self-compatible cultivars were used (Sáez et al. 2020). Currently, no self-compatible chestnut cultivar is available on the market, but attempts to breed partially self-compatible cultivars exist. Thus, two fundamental ecosystem services, wild pollenizers and wild pollinators, might become obsolete with the selection of new chestnut cultivars. This is a trend that deserves to be better documented. An early example of this trend is provided by grapevine, which was initially dioecious and pollinated by insects, and became hermaphroditic and self-fertile following domestication (Zito et al. 2018). This illustrates a rarely emphasized difficulty with the ecosystem service concept: the service itself may become obsolete because of breeding efforts. Developing agroecology will require addressing this reality and reorienting research and development.

5 Conclusion and perspectives

In principle, chestnut orchards can benefit from two pollination services. First, wild pollinators can act as pollen vectors. Second, wild chestnut trees can act as pollenizers. Pollination insurance provided by native forests is now quite low in southwestern France due to the increased reliance on Eurojapanese interspecific hybrid cultivars that are genetically isolated by crossing barriers from European chestnut. Consequently, in production orchards composed solely of hybrid cultivars, within orchard cultivar diversity is required. Adding new pollenizers in extant orchards implies either grafting or planting new cultivars or allowing rootstocks to grow into trees. To avoid such long and expensive catch-up phases, it is crucial to better design new orchards from the outset for effective pollination.

Availability of data and materials

• Datasets

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the Recherche Data Gouv repository, https://doi.org/10.57745/KRSIEX

• Code availability (software application or custom code)

The custom code and/or software application generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Arnold JB (2016) ggthemes: extra themes, scales and geoms for “ggplot2”

Barrett SCH, Lloyd DG, Arroyo J (1996) Stylar polymorphisms and the evolution of heterostyly in Narcissus (Amaryllidaceae). Floral Biology. Springer US, Boston, pp 339–376

Biton I, Many Y, Mazen A, Ben-Ari G (2020) Compatibility between “Arbequina” and “Souri” olive cultivars may increase souri fruit set. Agronomy 10:910. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10060910

Breisch H (1995) Châtaignes et Marrons. Centre technique interprofessionnel des fruits et légumes, Paris

Carisio L, Díaz SS, Ponso S et al (2020) Effects of pollinizer density and apple tree position on pollination efficiency in cv. Gala. Sci Horticult 273:109629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109629

de Oliveira D, Gomes A, Ilharco FA, et al (2001) Importance of insect pollinators for the production in the chestnut, Castanea sativa. Acta Horticult 269–273. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2001.561.40

Fernández-López J, Fernández-Cruz J, Míguez-Soto B (2021) The demographic history of Castanea sativa Mill. in southwest Europe: a natural population structure modified by translocations. Mol Ecol 30:3930–3947. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16013

Feurtey A, Cornille A, Shykoff JA et al (2017) Crop-to-wild gene flow and its fitness consequences for a wild fruit tree: Towards a comprehensive conservation strategy of the wild apple in Europe. Evol Appl 10:180–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12441

Furones-Pérez P, Fernández-López J (2009) Morphological and phenological description of 38 sweet chestnut cultivars (Castanea sativa Miller) in a contemporary collection. Span J Agric Res 7:829–843. https://doi.org/10.5424/sjar/2009074-1097

Gonthier P, Robin C (2019) Diseases. In: The Chestnut Handbook: Crop and Forest Management. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

Guajardo V, Hinrichsen P, Muñoz C (2017) Paternity analysis in a ‘Rainier’ open pollination population using S -alleles and microsatellite genotyping. Acta Hortic 21–26. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2017.1161.3

Guichoux E, Garnier-Géré P, Lagache L et al (2013) Outlier loci highlight the direction of introgression in oaks. Mol Ecol 22:450–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12125

Kalinowski ST, Taper ML, Marshall TC (2007) Revising how the computer program CERVUS accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol Ecol 16:1099–1106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03089.x

Kron P, Husband BC (2006) The effects of pollen diversity on plant reproduction: insights from apple. Sex Plant Reprod 19:125–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00497-006-0028-2

Larue C (2021) De la pollinisation à la formation des graines : le cas du châtaignier. PhD Thesis, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux

Larue C (2022) DATA: Strong pollen limitation in genetically uniform hybrid chestnut orchards despite proximity to chestnut forests. Recherche Data Gouv V1. https://doi.org/10.57745/KRSIEX

Larue C, Austruy E, Basset G, Petit RJ (2021a) Revisiting pollination mode in chestnut (Castanea spp.): an integrated approach. Bot Lett 168:348–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/23818107.2021.1872041

Larue C, Barreneche T, Petit RJ (2021b) An intensive study plot to investigate chestnut tree reproduction. Ann for Sci 78:90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-021-01104-w

Larue C, Barreneche T, Petit RJ (2021c) Efficient monitoring of phenology in chestnuts. Sci Hortic 281:109958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2021.109958

Larue C, Guichoux E, Laurent B et al (2021d) Development of highly validated SNP markers for genetic analyses of chestnut species. Conserv Genet Resour. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12686-021-01220-9

Larue C, Klein EK, Petit RJ (2022) Sexual interference revealed by joint study of male and female pollination success in chestnut. Mol Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.16820

Larue C, Petit RJ (2022) Self-interference and female advantage in chestnut. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.01.502348

Manino A, Patetta A, Marletto F (1991) Investigations on chestnut pollination. Acta Horticult 335–339. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1991.288.54

Mariotti R, Pandolfi S, De Cauwer I et al (2021) Diallelic self-incompatibility is the main determinant of fertilization patterns in olive orchards. Evol Appl 14:983–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.13175

Martín MA, Monedero E, Martín LM (2017) Genetic monitoring of traditional chestnut orchards reveals a complex genetic structure. Ann for Sci 74:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-016-0610-1

Meland M, Frøynes O, Akšić Fotiric M et al (2020) Identifying pollen donors and success rate of individual pollinizers in European plum (Prunus domestica L.) using microsatellite markers. Agronomy 10:264. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10020264

Mookerjee S, Guerin J, Collins G et al (2005) Paternity analysis using microsatellite markers to identify pollen donors in an olive grove. Theor Appl Genet 111:1174–1182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-005-0049-5

Nishio S, Takada N, Terakami S et al (2019) Estimation of effective pollen dispersal distance for cross-pollination in chestnut orchards by microsatellite-based paternity analyses. Sci Hortic 250:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2019.02.037

Peakall R, Smouse PE (2012) GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research–an update. Bioinformatics 28:2537–2539. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts460

Pereira-Lorenzo S, Ramos-Cabrer AM, Díaz-Hernández MB et al (2006) Chemical composition of chestnut cultivars from Spain. Sci Hortic 107:306–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2005.08.008

Pérez V, Herrero M, Hormaza JI (2016) Self-fertility and preferential cross-fertilization in mango (Mangifera indica). Sci Hortic 213:373–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2016.10.034

Petit RJ, Larue C (2022) Confirmation that chestnuts are insect-pollinated. Botany Letters 169:370–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/23818107.2022.2088612

Pinillos V, Cuevas J (2009) Open-pollination provides sufficient levels of cross-pollen in spanish monovarietal olive orchards. Horts 44:499–502. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.44.2.499

Pitte J-R (1986) Terres de Castanide, Fayard, Paris

Pons E, Navarro A, Ollitrault P, Peña L (2011) Pollen competition as a reproductive isolation barrier represses transgene flow between compatible and co-flowering citrus genotypes. PLoS ONE 6:e25810. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025810

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155:945–959

QGIS Development Team (2022) QGIS Geographic Information System. QGIS Association

R Core Team (2013) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienne

Reilly JR, Artz DR, Biddinger D et al (2020) Crop production in the USA is frequently limited by a lack of pollinators. Proc R Soc B 287:20200922. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.0922

Sáez A, Aizen MA, Medici S et al (2020) Bees increase crop yield in an alleged pollinator-independent almond variety. Sci Rep 10:3177. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59995-0

Shemer A, Biton I, Many Y et al (2014) The olive cultivar ‘Picual’ is an optimal pollen donor for ‘Barnea.’ Sci Hortic 172:278–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2014.04.017

Soylu A (1992) Heredity of male sterility in some chestnut cultivars (Castanea sativa mill.). Acta Horticulturae 181–186. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1992.317.21

Stout AB (1926) Why are chestnuts self-fruitless? J N Y Botan Garden 27:154–158

Vuletin Selak G, Baruca Arbeiter A, Cuevas J et al (2021) Seed paternity analysis using SSR markers to assess successful pollen donors in mixed olive orchards. Plants 10:2356. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10112356

Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York

Wilcock CC, Neiland MRM (2002) Pollination failure in plants: why it happens and when it matters. Trends Plant Sci 7:270–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02258-6

Wilke CO (2020) cowplot: Streamlined Plot Theme and Plot Annotations for “ggplot2”

Xiong H, Zou F, Guo S et al (2019) Self-sterility may be due to prezygotic late-acting self-incompatibility and early-acting inbreeding depression in Chinese chestnut. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 144:172–181. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS04634-18

Xu F, Yang X, Zhao N et al (2022) Exploiting sterility and fertility variation in cytoplasmic male sterile vegetable crops. Horticult Res 9:uhab039. https://doi.org/10.1093/hr/uhab039

Ying Z, Davenport TL, Zhang T et al (2009) Selection of highly informative microsatellite markers to identify pollen donors in ‘Hass’ avocado orchards. Plant Mol Biol Rep 27:374–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-009-0108-1

Zito P, Serraino F, Carimi F et al (2018) Inflorescence-visiting insects of a functionally dioecious wild grapevine (Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris). Genet Resour Crop Evol 65:1329–1335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-018-0616-7

Acknowledgements

Production orchards were selected with the help of N. Lebarbier. We warmly thank the orchard owners, P. Lacoste, M. Duberteix, M. Feneteau, and P. Gay for allowing us to use their production orchards for this study. We thank C. Lalanne, J. Dudit, and M. Martin-Clotte for their invaluable assistance to prepare samples for DNA isolation. SNP development and genotyping were performed at the Genome Transcriptome Facility of Bordeaux (PGTB) with the help of E. Guichoux, M. Massot, A. Delcamp, C. Boury, and L. Dubois.

Funding

This paper was part of the PhD of CL. The Cifre thesis (Conventions Industrielles de Formation par la Recherche) was supported by the ANRT (Association Nationale de la Recherche de la Technologie, convention Cifre N° 2018/0179). It was funded by Invenio, the Région Nouvelle-Aquitaine (Regina project N° 22001415–00004759 and chestnut pollination project N° 2001216–00002632), by INRAE (Institut National de Recherche pour l'Agriculture et l'Environnement). Further analyses and writing were supported through ANR (project ANR-21-PRRD-0008–01). The PGTB facility, where part of the work was conducted, benefits from grants from the Conseil Régional d’Aquitaine no. 20030304002FA and 20040305003FA, from the European Union FEDER no. 2003227 and from Investissements d’Avenir (ANR-10-EQPX-16–01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: [Clément LARUE, Rémy J PETIT]; Methodology: [Clément LARUE, Rémy J PETIT]; Formal analysis and investigation: [Clément Larue]; Writing—original draft preparation: [Clément Larue]; Writing—review and editing: [Rémy J PETIT]; Funding acquisition: [Clément LARUE, Rémy J PETIT]; Resources: [Clément LARUE]; Supervision: [Rémy J PETIT]. All author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors declare that the study was not conducted on endangered, vulnerable, or threatened species. This research paper does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

“Not applicable”—This work does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

“Not applicable”—This work does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Additional information

Handling editor: Marjana Westergren.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A. Structure Parameters

An initial analysis was performed to assign fruit from the three orchards to the different chestnut species. Rather than using the default alpha value calculated with all samples which is a source of inaccuracy (Fernández‐López et al. 2021), we calculate an average alpha with only the reference genotypes. This alpha coefficient corresponds to the value with which the Markov chain starts in the STRUCTURE software. We set K from 3 to 3 performed 6 Monte Carlo chains of 100,000 repetitions after a burn-in period of 50,000 repetitions and computed mean ALPHA value which is estimated at 0.0286. A first dataset is used to calculate alpha: this file gathers the 64 well-known genotypes belonging to the pure species of the INRAE collection typed with 65 SNPs (Larue et al. 2021c).

Then each genotype is associated with a species: in the “putative population” column C. crenata is coded 1 C. mollissima is coded 2 and C. sativa is coded 3. These genotypes are used as a reference to define the species: allelic frequencies are calculated only with these 64 reference genotypes and each genotyped sample from the five studied orchards is assigned to one of the three chestnut species. A second data file is used and it contains the 64 pure species genotypes of the INRAE collection as well as the trees and fruits genotyped in production orchards typed with 65 SNPs. New samples from unknown species are coded 4 for the column “putative population.” For the column "POPFLAG", the reference samples are coded 1 while samples from the five studied orchards are coded 0. Then the software will define the species with the known samples (Putative POPFLOG = 1 and Putative population =1/2/3) and will assign the samples of unknown origin (POPFLOG = 0 and Putative population =4) to the three chestnut species. This second analysis was performed with the default parameters of STRUCTURE except for the Ancestry model where we defined the alpha value of the admixture model thanks to the analysis performed with the 64 reference genotypes (alpha = 0.03). In the advanced parameters, we specify that only the individuals with POPFLAG = 1 are used to calculate the allelic frequencies of the different species. The value of K was set to three and three Monte Carlo chains of 100,000 repetitions after a burn-in period of 50,000 repetitions were run. Since the results were very close, the results of the run with the highest likelihood are used for this first exploratory analysis.

-

a)

Structure analysis 1

Parameters set:

Running Length

Length of Burnin Period: 50000

Number of MCMC Reps after Burnin: 100000

Ancestry Model Info

Use Admixture Model

* Infer Alpha

* Initial Value of ALPHA (Dirichlet Parameter for Degree of Admixture): 1.0

* Use Same Alpha for all Populations

* Use a Uniform Prior for Alpha

** Maximum Value for Alpha: 10.0

** SD of Proposal for Updating Alpha: 0.025

Frequency Model Info

Allele Frequencies are Correlated among Pops

* Assume Different Values of Fst for Different Subpopulations

* Prior Mean of Fst for Pops: 0.01

* Prior SD of Fst for Pops: 0.05

* Use Constant Lambda (Allele Frequencies Parameter)

* Value of Lambda: 1.0

Advanced Options

Estimate the Probability of the Data Under the Model

Frequency of Metropolis update for Q: 10

Run parameters:

Start Job

Set K from 3 to 3

Number of Iterations: 6

-

b)

Structure analysis 2

Parameters set:

Running Length

Length of Burnin Period: 50000

Number of MCMC Reps after Burnin: 100000

Ancestry Model Info

Use Prior Population Information to Assist Clustering

* GENSBACK = 2

* MIGRPRIOR = 0.05

* For Individuals without population information data use

Admixture Model

** Use Constant Alpha Value

** Value of Alpha (Dirichlet Parameter for Defree of Admixture): 0.03

Frequency Model Info

Allele Frequencies are Correlated among Pops

* Assume Different Values of Fst for Different Subpopulations

* Prior Mean of Fst for Pops: 0.01

* Prior SD of Fst for Pops: 0.05

* Use Constant Lambda (Allele Frequencies Parameter)

* Value of Lambda: 1.0

Advanced Options

Update Allele Frequencies using Individuals with POPFLAG=1 ONLY

Estimate the Probability of the Data Under the Model

Frequency of Metropolis update for Q: 10

Run parameters:

Start Job

Set K from 3 to 3

Number of Iterations: 6

1.2 B. Parameters used in paternity analysis with CERVUS

-

a)

Seeds with C. sativa fathers

-

1.

Allelic frequencies calculated with the 56 C. sativa unique genotypes

-

2.

Simulation for paternity analyses:

-

100 000 offspring

-

Candidate fathers = 56 / Pop. Sampled = 0.20

-

SNP: Prop. loci typed = 0.95 / Prop. loci mistyped = 0.03

-

Confidence = Delta

-

Confidence levels = Relaxed = 95% / Strict = 99%

-

Min loci typed = 34

-

Tests for self-fertilisation not allow

-

-

3.

Genotypes: 56 C. sativa and 253 seeds

-

Paternity analysis: identify the most-likely parent

-

-

1.

-

b)

Seeds with C. crenata or Eurojapanese fathers

-

1)

Allelic frequencies calculated with the 4 C. crenata and 13 Eurojapanese unique genotypes

-

2)

Simulation for paternity analyses:

-

100 000 offspring

-

Candidate fathers = 17 / Pop. Sampled = 0.80

-

SNP: Prop. loci typed = 0.95 / Prop. loci mistyped = 0.03

-

Confidence = Delta

-

Confidence levels = Relaxed = 95% / Strict = 99%

-

Min loci typed = 34

-

Tests for self-fertilisation allow

-

-

3)

Genotypes: 4 C. crenata 13 Eurojapanese and 337 seeds

-

Paternity analysis: identify the most-likely parent

-

-

1)

Mother trees are Eurojapanese hybrids. For the first analysis only with seeds whose father is a C. sativa, we exclude their genotypes from allelic frequencies file and we don’t test self-fertilization because fathers are C. sativa genotypes not Eurojapanese. For the second analysis only with seeds whose father is C. crenata or Eurojapanese; mother genotypes are included in allelic frequencies file because they are interspecific hybrids, and we allow self-fertilization.

1.3 C. Results of paternity analysis on seeds sired by C. sativa trees.

1.4 D. Results of paternity analysis on seeds sired by Eurojapanese hybrids and by C. crenata trees

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Larue, C., Petit, R.J. Strong pollen limitation in genetically uniform hybrid chestnut orchards despite proximity to chestnut forests. Annals of Forest Science 80, 37 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13595-023-01188-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13595-023-01188-6