Abstract

Background

Papillary breast lesions may be benign, atypical, and malignant lesions. Pathological and clinical differentiation of breast papillomas can be a challenge. Unlike malignant lesions, benign breast papillomas are not classically associated with lymph node and distant metastasis. We report a unique case of a recurrent, benign breast papilloma presenting as an aggressive malignant tumor.

Case presentation

Our patient was a 56-year-old postmenopausal African American woman who was followed in the breast clinic with a long history of multiple breast papillomas. She underwent multiple resections over the course of 7–9 years. After being lost to follow-up for 2 years, she once again presented with a slowly enlarging left breast mass. Subsequent imaging revealed a predominantly cystic mass in the left breast, as well as a suspicious hypermetabolic internal mammary node and a hypermetabolic nodule in the pretracheal space. Biopsy of the internal mammary node demonstrated papillary neoplasm with benign morphology and immunostains positive for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/Neu. Due to the clinical picture concerning for malignancy, the patient was then started on endocrine therapy with palbociclib and letrozole before surgery. She then underwent simple mastectomy and sentinel lymph node dissection with negative nodes and pathology once again revealing benign papillary neoplasm. She underwent adjuvant chest wall radiation for 6 weeks and received letrozole following completion of her radiation therapy. She was without evidence of disease 30 months after surgery.

Conclusions

We present an unusual case of multiple recurrent peripheral papillomas with entirely benign histologic features exhibiting malignant behavior over a protracted period of many years, with an invasion of pectoralis musculature and possibly internal mammary and mediastinal nodes. Her treatment course included multiple surgeries (ultimately mastectomy), radiation therapy, and endocrine therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Papillary lesions of the breast comprise a wide spectrum of tumors with varying clinical presentations and histopathological characteristics. That said, they constitute less than 2% of all breast lesions [1, 2]. The defining histology of these lesions is epithelial proliferation with fibrovascular core support with or without myoepithelial (ME) cells. These lesions may be benign, malignant, or atypical [3]. Papillomas with atypia are associated with up to a four times increased risk of malignant transformation, and unlike benign papillomas, malignant papillary lesions may be associated with lymph node and distant metastases [2, 4]. Benign breast papillomas presenting with local or distant metastases have been reported very rarely [5,6,7,8]. We present an unusual case of an African American woman with a recurrent, benign breast papilloma with malignant behavior.

Case presentation

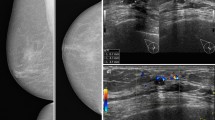

Our patient was a 56-year-old postmenopausal African American woman with no past medical history who was previously treated at an outside oncology clinic for breast masses until 2010, when we first saw her. Her family history was negative for breast or ovarian carcinoma. She had a negative smoking history and endorsed drinking one drink per week. Per reports obtained, she first presented in 2006 with left breast lesions located in the upper inner breast that were documented as complicated cystic masses within the 9 o’clock and 9:30 positions on the basis of ultrasound (US). Subsequent US core biopsy in both areas revealed intraductal papilloma (IDP), and the patient was referred for a surgical consultation. No additional documentation of clinical visits was available until 1 year later. That documentation was in the form of a core biopsy pathologic report documenting the patient’s history of IDP at 9:00 and 9:30 positions as well as intraductal papillomatosis of the breast. A core biopsy taken at that time was from the left breast (location not mentioned) as well as the left axilla. The patient’s left breast showed fibrosis of mammary stroma including intralobular stromal sclerosis as well as microcalcifications in the lobular lumens. An axillary core biopsy confirmed IDP of the breast with stromal hyalinization as well as lymph node tissue adjacent to the papilloma. One month later, she underwent lumpectomy, with pathology reporting a 7-mm intracystic papilloma within a lymph node that was completely excised, as well as an epidermal inclusion cyst. The pathologist noted that the tumor was located near the periphery of a lymph node, probably arising in ectopic breast tissue in the capsular region. Approximately 11 months later, she developed another left breast mass. This was excised after a US-guided core biopsy once again revealed a benign IDP. The patient was then lost to follow-up at the outside clinic. She presented to our clinic 2 years later for an evaluation of a new left breast lesion. A bilateral diagnostic mammogram revealed two masses in the left breast, which were not well visualized, owing to heterogeneously dense breast tissue. Diagnostic US revealed a solid superficial mass measuring 0.81 × 0.76 × 0.81 cm corresponding to palpable findings also seen at the 6 o’clock position (Fig. 1a). Additionally, the patient had a large, complex cystic mass measuring 7 cm at the 1 to 3 o’clock position abutting the pectoralis muscle (Fig. 1a). A core biopsy of the 6 o’clock lesion was recommended. A US-guided, vacuum-assisted core biopsy of the 6 o’clock mass revealed an intracystic papillary neoplasm. Per the report, the patient denied nipple discharge, dimpling, thickening, redness of the skin, swelling, or tenderness at the time. A few weeks later, she underwent left breast lumpectomy with pathology revealing a complex cystic mass with fibrocystic changes at 1 to 3 o’clock and intraductal papilloma at 6 o’clock. The patient missed her 6-month follow-up mammogram. She returned 8 months later for a bilateral diagnostic mammogram, which showed a new 2.5-cm mass in the deep central aspect of her left breast at the 12 o’clock position. US showed a cystic mass measuring 3 cm and containing an intracystic solid component measuring 1 × 1 × 2 cm. No axillary or supraclavicular adenopathy was noted on the basis of imaging or physical examination. Her surgical team decided on left breast excisional biopsy with preoperative mammogram guidewire localization. Pathology revealed a benign papilloma measuring 1 cm, focally extending into skeletal muscle in the area adjacent to the previous biopsy site, but with negative margins and no signs of atypia. On the patient’s 6-month follow-up surveillance diagnostic mammogram, another new 3-cm density was noted at the 12 o’clock position. This was most consistent with a benign cyst and was aspirated. She was again lost to follow-up for more than 2 years until July 2015, when she presented with a 2-month history of a slowly enlarging left breast mass in the same region as her previous papillomas. A bilateral diagnostic mammogram with US showed a large mass at the 12 o’clock position measuring 7 × 2.5 cm. Her physical examination revealed that there were two areas of concern: first, a mass measuring 7.5 × 6.3 cm in the 1 o’clock position, and second, an area of nodularity measuring 4.6 × 3.1 cm in the 11 o’clock position. One month later, computed tomography (CT) of the chest and magnetic resonance imaging of the breast revealed a predominantly cystic mass with a solid component extending into the chest wall and approaching the pleural space (Fig. 2). These tests also revealed a suspicious internal mammary lymph node (Fig. 3a). A positron emission tomographic (PET)-CT scan showed a hypermetabolic nodule located in the pretracheal space (Fig. 3b) with a corresponding standardized uptake value (SUV) of 6.1 and multiple associated hypermetabolic internal mammary lymph nodes with the highest SUV of 6.0 and nodular hypermetabolic activity along the inferomedial aspect of the cystic mass (SUV, 2.7).

Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast with/without contrast enhancement. a Large cystic mass (white arrow) extending through the pectoralis muscle and containing a 1.8-cm area of neoplastic enhancement internally. This lesion was hypermetabolic on the positron emission tomographic scan. b An abnormal left internal mammary lymph node (white arrow) at the level of the sternomanubrial articulation. This was confirmed to be metastatic on the basis of biopsy

Comparison of positron emission tomographic/computed tomographic image from 2015 (prior to neoadjuvant antihormonal therapy and left breast mastectomy) versus follow-up image in 2018 (following left breast mastectomy). a Response was noted in the internal mammary lymph node following combination antihormonal therapy (arrow). b18F-fluorodeoxyglucose avid mediastinal lymphadenopathy with mild reduction in avidity following combination antihormonal therapy (arrow). Of note, no avidity was seen in the internal mammary lymph node, and minimal avidity surrounding the breast papillary mass was observed. c Mass in 2015 prior to antihormonal therapy and mastectomy. Note the size of this mass. d Reconstructed breast following mastectomy

Her case was discussed at the multidisciplinary breast tumor board, and the recommendation was to proceed with a biopsy of the left internal mammary lymph nodes. Core biopsy revealed a papillary neoplasm with benign morphology with immunostains positive for estrogen receptor (ER) at 99%, positive for progesterone receptor (PR) at 85%, HER2/neu 1+, and a Ki67 proliferation index of 6%. An independent external pathologist agreed with the finding of histologically benign papilloma. The patient sustained a biopsy-related internal mammary artery injury and as a result developed a hemothorax requiring video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Upon recovery from the hemothorax, the patient was referred to the medical oncology department of our hospital. Given the malignant behavior of her tumor, a recommendation of aggressive local control was made. She was started on endocrine therapy with palbociclib and letrozole as a neoadjuvant strategy. Repeat PET-CT following 4 months of combination antiestrogen therapy demonstrated near-complete resolution of metastatic internal mammary lymph nodes (white arrows in Fig. 3a) and reduced size and avidity of the paratracheal nodes (arrows in Fig. 3b). A physical examination did not show any significant changes in the size of the left breast mass. She went on to complete 6 months of neoadjuvant therapy. The primary lesion demonstrated minimal clinical response after 6 months of combination endocrine therapy, and then she underwent a left simple mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Once again, the pathology revealed a 7.1-cm papillary neoplasm described as microscopically bland and mitotically inactive, with a retained ME layer. Several similar-appearing satellite papillomatous lesions were also seen within the skeletal muscle and deep adipose tissue. Margins and all five sentinel lymph nodes were negative (Figs. 4 and 5).

Left internal mammary node core biopsy. a Well-demarcated papillary neoplasm in fibroadipose tissue. No lymph node structure was identified. b Medium-power view of papillary neoplasm. Prominent fibrovascular cores with bland columnar cell lining. c p63 immunohistochemical stain highlights the intact myoepithelial layer beneath the columnar lining

Given the extent of her local involvement and history of recurrent disease, she underwent adjuvant chest wall radiation for 6 weeks, followed by adjuvant endocrine therapy with letrozole. Six months after mastectomy, a repeat PET-CT scan showed no evidence of disease. She continues to undergo surveillance CT of the chest and mammography of her right breast. One year after her mastectomy, she underwent left breast reconstruction (Fig. 3d). She remained without evidence of disease 2.5 years after mastectomy and continued on endocrine therapy during that time.

Discussion

Papillary lesions, per the World Health Organization classification, are classified as benign papillomas, papillomas with atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH), papillomas with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), intraductal papillary carcinoma (IPC), encapsulated papillary carcinoma (EPC), solid papillary carcinoma (SPC), and invasive papillary carcinoma [9]. Clinically, SPC and EPC are regarded as variants of IPC [3]. On occasion, morphological distinction between a benign and a malignant papillary lesion can be challenging. Although the absence of an intact ME cell layer in the fibrovascular core suggests carcinoma, its presence does not always exclude malignancy [10,11,12,13]. Invasive growth and high-grade nuclei support carcinoma [14]. Also, very few cases have been reported of metastases from benign papillomas, and all of them were reported as metastases to the axillary lymph node [5,6,7,8]. To our knowledge, we report the first case of a benign breast papilloma extending into the chest wall and also involving the internal mammary node.

Papillary lesions are categorized as central (involving large, lactiferous ducts) or peripheral (involving terminal ductal lobular unit), based on location [15]. Central IDPs are classically solitary and are more common than peripheral IDPs, which usually are multiple. Solitary and central IDPs are associated with atypia or DCIS less frequently than multiple and peripheral IDPs are [16]. Further, the presence of ADH or DCIS in papillomas is associated with a risk of subsequent malignancy, which varies widely (7–67%) [1, 17,18,19,20]. Our patient’s central intracystic papilloma was not associated with atypia or DCIS, but the clinical behavior was suspicious for a malignant papillary lesion. Of note, IPCs are rare, but they are an essential part of the differential diagnosis of papillary lesions [21].

Interestingly, papillary lesions are innately friable and susceptible to epithelial displacement following a fine-needle aspiration or core-needle biopsy. The epithelial displacement can occur into the biopsy site, lymphatic channels, or axillary lymph nodes. Understanding this phenomenon helps to prevent misdiagnosis and differentiate benign from potential metastatic lesions [22, 23].

Central IDPs can occur at any age, but they are prevalent between the ages of 40 and 60 years [17]. Similar to our patient, patients with central IDPs classically present with a palpable breast mass with or without nipple discharge and a well-defined mass on a mammogram. In contrast, peripheral IDPs occur in younger patients and are often clinically occult and diagnosed incidentally as microcalcifications during screening mammography [24].

IPC generally occurs in older patients. About half of these cases arise centrally, commonly have associated bloody nipple discharge, and 90% have a palpable mass [25]. On mammography, IPCs appear as rounded, well-circumscribed lesions. Patients with IPC are rarely associated with lymph node involvement and distant metastasis and generally have an excellent prognosis, with a 5-year survival greater than 80% [3, 26, 27].

The treatment strategy for papillary lesions of the breast is debatable because there is always a high suspicion of harboring malignant lesions. For example, atypical papillomas are associated with high rates of malignant upgrades (as high as 42%), and hence surgical excision is the current standard of care [28,29,30]. By contrast, benign papillomas demonstrate malignant upgrade at rates less than 10%, and management can vary from conservative radiologic follow-up to surgical excision [31, 32]. However, many experts also advocate complete surgical excision due to sampling errors at the time of the biopsy and tumor heterogeneity with atypical or malignant foci [19, 33,34,35]. Local recurrence of solitary papilloma after surgical excision is also uncommon, occurring in less than 10% of cases [27, 36]. Compared with our patient’s case, multiple recurrences are rare, even with a malignant papillary lesion. As a result, surveillance imaging and follow-up per institutional and national guidelines are recommended.

Given its low malignant potential and low proliferative index, chemotherapy is not recommended for the treatment of IPC [37]. The majority of IPC cases express ER and PR. Adjuvant endocrine therapy, therefore, remains an option. For benign papillary lesions, secondary systemic therapies are not recommended, although primary prevention with antiestrogen therapy may be recommended on the basis of a patient’s risk assessment [38]. In our patient, the pattern of recurrence, including muscle invasion, tumor size, and intramammary nodal involvement, was atypical, pointed to a more malignant tumor behavior, and was therefore approached in a more aggressive manner. No evidence exists for the use of combination antiestrogen therapy or CDK4/6 inhibitor therapies for the treatment of potentially curable invasion or benign papillary carcinomas. Ultimately, this patient appears to have benefited from this approach.

Conclusion

We present an unusual case of a patient with multiple recurrent peripheral papillomas with entirely benign histologic features exhibiting malignant behavior over a protracted period of many years, including invasion of pectoralis musculature, internal mammary, and possibly paratracheal lymph nodes. Her treatment course included multiple surgeries (ultimately mastectomy), radiation, and endocrine therapy. The patient was disease-free 32 months after mastectomy.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Renshaw AA, Derhagopian RP, Tizol-Blanco DM, Gould EW. Papillomas and atypical papillomas in breast core needle biopsy specimens: risk of carcinoma in subsequent excision. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:217–21.

Greif F, Sharon E, Shechtman I, Morgenstern S, Gutman H. Carcinoma within solitary ductal papilloma of the breast. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:384–6.

Pal SK, Lau SK, Kruper L, Nwoye U, Garberoglio C, Gupta RK, Paz B, Vora L, Guzman E, Artinyan A. Papillary carcinoma of the breast: an overview. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:637–45.

Khan S, Diaz A, Archer KJ, Lehman RR, Mullins T, Cardenosa G, Bear HD. Papillary lesions of the breast: to excise or observe? Breast J. 2018;24:350–5.

Ichihara S, Ikeda T, Kimura K, Hanatate F, Yamada F, Hasegawa M, Moritani S, Yatabe Y. Coincidence of mammary and sentinel lymph node papilloma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:784–92.

Singh T, Tso E, Kumar A, Ahrens P. Axillary lymph node metastases from papilloma of the breast [abstract]. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18 Suppl):10764.

Dzodic R, Stanojevic B, Saenko V, Nakashima M, Markovic I, Pupic G, Buta M, Inic M, Rogounovitch T, Yamashita S. Intraductal papilloma of ectopic breast tissue in axillary lymph node of a patient with a previous intraductal papilloma of ipsilateral breast: a case report and review of the literature. Diagn Pathol. 2010;5:17.

Cottom H, Rengabashyam B, Turton PE, Shaaban AM. Intraductal papilloma in an axillary lymph node of a patient with human immunodeficiency virus: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:162.

Tse G, Moriya T, Niu Y. Invasive papillary carcinoma. In: WHO classification of tumours. Vol. 4: WHO classification of tumours of the breast. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2012. p. 64.

Collins LC, Schnitt SJ. Papillary lesions of the breast: selected diagnostic and management issues. Histopathology. 2008;52:20–9.

Choi YD, Gong GY, Kim MJ, Lee JS, Nam JH, Juhng SW, Choi C. Clinical and cytologic features of papillary neoplasms of the breast. Acta Cytol. 2006;50:35–40.

Gomez-Aracil V, Mayayo E, Azua J, Arraiza A. Papillary neoplasms of the breast: clues in fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathology. 2002;13:22–30.

Ueng SH, Mezzetti T, Tavassoli FA. Papillary neoplasms of the breast: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:893–907.

Agoumi M, Giambattista J, Hayes MM. Practical considerations in breast papillary lesions: a review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:770–90.

Ohuchi N, Abe R, Takahashi T, Tezuka F. Origin and extension of intraductal papillomas of the breast: a three-dimensional reconstruction study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1984;4:117–28.

Foley NM, Racz JM, Al-Hilli Z, Livingstone V, Cil T, Holloway CM, Romics L Jr, Matrai Z, Bennett MW, Duddy L, et al. An international multicenter review of the malignancy rate of excised papillomatous breast lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(Suppl 3):S385–90.

Lewis JT, Hartmann LC, Vierkant RA, Maloney SD, Pankratz VS, Allers TM, Frost MH, Visscher DW. An analysis of breast cancer risk in women with single, multiple, and atypical papilloma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:665–72.

Page DL, Salhany KE, Jensen RA, Dupont WD. Subsequent breast carcinoma risk after biopsy with atypia in a breast papilloma. Cancer. 1996;78:258–66.

Jaffer S, Nagi C, Bleiweiss IJ. Excision is indicated for intraductal papilloma of the breast diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Cancer. 2009;115:2837–43.

Sohn V, Keylock J, Arthurs Z, Wilson A, Herbert G, Perry J, Eckert M, Smith D, Groo S, Brown T. Breast papillomas in the era of percutaneous needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2979–84.

Wei S. Papillary lesions of the breast: an update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:628–43.

Carter BA, Jensen RA, Simpson JF, Page DL. Benign transport of breast epithelium into axillary lymph nodes after biopsy. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:259–65.

Youngson B, Cranor M, Rosen P. Epithelial displacement in surgical breast specimens following needling procedures. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:896–903.

Brookes M, Bourke A. Radiological appearances of papillary breast lesions. Clin Radiol. 2008;63:1265–73.

Rosen PP, Hoda SA. Breast pathology: diagnosis by needle core biopsy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

Lefkowitz M, Lefkowitz W, Wargotz ES. Intraductal (intracystic) papillary carcinoma of the breast and its variants: a clinicopathological study of 77 cases. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:802–9.

Grabowski J, Salzstein SL, Sadler GR, Blair S. Intracystic papillary carcinoma: a review of 917 cases. Cancer. 2008;113:916–20.

Fu CY, Chen TW, Hong ZJ, Chan DC, Young CY, Chen CJ, Hsieh CB, Hsu HH, Peng YJ, Lu HE. Papillary breast lesions diagnosed by core biopsy require complete excision. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:1029–35.

Yu Y, Salisbury E, Gordon-Thomson D, Yang JL, Crowe PJ. Management of papillary lesions without atypia of the breast diagnosed on needle biopsy. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:524–8.

Hong YR, Song BJ, Jung SS, Kang BJ, Kim SH, Chae BJ. Predictive factors for upgrading patients with benign breast papillary lesions using a core needle biopsy. J Breast Cancer. 2016;19:410–6.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Image-guided vacuum-assisted excision biopsy of benign breast lesions. Interventional Procedures Guidance 156. 22 Feb 2006. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg156/resources/imageguided-vacuumassisted-excision-biopsy-of-benign-breast-lesions-pdf-1899863283488965. Accessed 28 Nov 2019.

Swapp RE, Glazebrook KN, Jones KN, Brandts HM, Reynolds C, Visscher DW, Hieken TJ. Management of benign intraductal solitary papilloma diagnosed on core needle biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:1900–5.

Jagmohan P, Pool FJ, Putti TC, Wong J. Papillary lesions of the breast: imaging findings and diagnostic challenges. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:471.

Skandarajah AR, Field L, Mou AYL, Buchanan M, Evans J, Hart S, Mann GB. Benign papilloma on core biopsy requires surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2272–7.

Holley SO, Appleton CM, Farria DM, Reichert VC, Warrick J, Allred DC, Monsees BS. Pathologic outcomes of nonmalignant papillary breast lesions diagnosed at imaging-guided core needle biopsy. Radiology. 2012;265:379–84.

Ali-Fehmi R, Carolin K, Wallis T, Visscher DW. Clinicopathologic analysis of breast lesions associated with multiple papillomas. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:234–9.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Breast cancer (version 3.2019). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2019.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast cancer risk reduction (version 1.2019). https://www2.tri-kobe.org/nccn/guideline/breast/english/breast_risk.pdf. Accessed 28 Nov 2019.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding for this report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ALJ, JM, and GAV conceived and designed the study; acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data; and drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. JRS, FH, PV, AC, JR, EM, HR, MB, DR, and LS drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional review board approval was obtained.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors have no affiliation with any organization with a direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in this report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jain, A.L., Mullins, J., Smith, J.R. et al. Unusual recurrent metastasizing benign breast papilloma: a case report. J Med Case Reports 14, 33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-020-2354-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-020-2354-7