Abstract

Background

Peritoneal metastases are often reported in several abdominal tumors. Peritoneal diffusion from extra-abdominal tumors is thought to be rare. Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in the world with early metastases and it is associated with poor prognosis in advanced stages. Peritoneal metastases from lung cancer are uncommon and the real mechanism of its diffusion to the peritoneum is unknown. However, its clinical behavior is similar to any other peritoneal metastasis from abdominal tumors.

Case presentation

We present two Caucasian patients (a 44-year-old man and a 59-year-old man) with bowel obstruction from peritoneal metastases from non-small cell lung cancer who successfully underwent emergency cytoreductive surgery and had a good prognosis and survival.

Conclusions

In our patients with isolated peritoneal metastases from lung cancer, cytoreduction showed good prognosis with acceptable morbidity. This treatment option might be considered in highly selected cases to improve survival. Strict follow-up is mandatory to allow early diagnosis of peritoneal diffusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The occurrence of peritoneal metastases represents the clinical final stage of several tumors: most commonly ovarian, colorectal, gastric cancers, and, less frequently, appendix cancer. In recent years, the inclusion of cytoreductive surgery, alone or associated with locoregional chemotherapy, in the treatment strategy of some of these conditions has increased (peritoneal metastases from ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal malignancies), whereas its application remains mainly investigational in other conditions (gastric, colorectal, endometrial, and breast cancers) [1, 2].

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide. It is the leading cause of death from cancer; diagnosis is often made at an advanced stage when metastases have already spread to the other lung, to the liver, to the brain, to the bone, and to adrenal glands [3].

Few reports are available in the literature about patients with peritoneal metastases from lung cancer [4,5,6]. Despite any treatment, overall survival for these patients is very poor, with reported rates of 9 months in a recent series [5].

We describe two cases of diffused peritoneal metastases from lung cancer who underwent emergency cytoreductive surgery for bowel occlusion and had an unexpectedly good prognosis and long-term survival.

Cases presentation

Patient 1

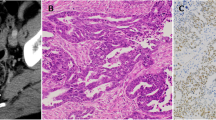

In March 2013, a 44-year-old Caucasian man, a non-smoker of tobacco, was referred to our department as an emergency with 3 days’ history of bowel obstruction. His family history was negative for cancer. His past medical history included a right pneumonectomy in 2009 for a T2, N1, M0 G3, stage IIB lung adenocarcinoma. Immunohistochemistry was positive for cytokeratin 7 and negative for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2 (CDX2), cytokeratin 20, protein S100, thyroglobulin, the anti-melanosome clone, human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45), and the anti-melanoma, melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1). After surgery, he underwent four cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin (100 mg/m2) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m2); he then received two cycles of gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) after the fourth cycle of cisplatin and paclitaxel for a grade 4 toxicity to paclitaxel. On admission in our department, he was off any treatment, and 1 month previously he had negative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for brain metastases. His vital signs were normal. Performance status assessed by the Eastern Cooperative Oncologic Group (ECOG) [7] was 1. He had been vomiting and his bowel had been obstructed for 24 hours. A clinical examination revealed a tender distended abdomen. Blood tests were normal except for neutrophilic leukocytosis: white blood cells (WBC) 14,000/mm3. Neuron-specific enolase and cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1) levels were normal (respectively 121 ng/ml and < 3 ng/ml). A total body contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed a distended large bowel with air-fluid levels and multiple neoplastic implants involving the right colon, greater omentum, spleen, and the sigmoid colon, ranging from 0.5 to 10 cm. (Fig. 1). No other pathological findings were disclosed and a chest examination was negative except for the outcomes of the previous thoracic surgery (Fig. 2).

Considering his young age, the absence of lung recurrence and of any other distant metastasis, palliative surgery was considered in order to treat bowel obstruction. At laparotomy there was no ascites, and three gross neoplastic implants were found in the greater omentum, right colonic flexure, transverse colon, and left colon. Extensive cytoreductive surgery was performed and surgical procedures included subtotal colectomy with ileosigmoid anastomosis, splenectomy, and greater omentectomy (Figs. 3 and 4). At the end of the procedure no residual macroscopic disease was left, reaching a completeness of cytoreduction score (CCS) of 0.

Pathology showed complete infiltration of the colonic wall and spleen by adenocarcinoma nodules with lymph node metastases in the mesocolon.

Immunohistochemistry evaluation showed the same staining as the previous lung adenocarcinoma, confirming the lung origin of the peritoneal metastases.

His postoperative course was complicated by fever (38.5 °C) and dyspnea on postoperative day 9. A chest X-ray showed a “ground glass” picture of left lung and bloodstream and expectorate cultures were positive for Candida albicans species. Intravenously administered anidulafungin treatment was started with rapid improvement of our patient’s general condition and gradual resolution of sepsis. He was discharged on postoperative day 20 and subsequently he underwent six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with cisplatin (100 mg/m2). Considering the previous toxicity to paclitaxel no other drug was used. A follow-up protocol included clinical evaluation (1 month after surgery, then every 3 months), blood tests with tumor marker levels every 3 months, and total body CT scan 1 month after surgery, then every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months for the next 2 years. Yearly, a brain MRI was scheduled. He was alive and disease free 3 years after surgery. In September 2016 he was lost to follow-up.

Patient 2

In September 2011, a 59-year-old Caucasian man, a heavy tobacco smoker, presented to our department as an emergency with abdominal pain and vomiting. His past medical history included a left upper lobectomy for a T1N1M0, G3 stage IIB lung adenocarcinoma (3 years before) followed by six cycles of systemic chemotherapy (carboplatin + paclitaxel 175 mg/m2). His family history was positive for cancer (a 39-year-old brother died of colon cancer). Two days before admission, abdominal distension and bowel obstruction occurred and progressively worsened. His WBC count was 18,000/mm3. A total body CT scan showed a large mass involving the distal ileal loops with obstruction and distension of the proximal bowel, with a small amount of ascites in his pelvis.

He underwent explorative laparoscopy that confirmed the CT scan findings, showing no other peritoneal seeding. Ascites was taken for cytological examination, and a laparoscopic ileocolic resection with ileotransverse anastomosis was performed, reaching a CCS of 0. His postoperative course was uneventful and he was discharged on postoperative day 4. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of metastasis from adenocarcinoma; ascites was found to be negative for neoplastic cells. At immunohistochemistry, cancer cells were positive for cytokeratin 7 and TTF-1 confirming the origin of peritoneal metastases from the lung cancer. He was followed by medical oncologists and, due to his poor general condition, he underwent a second-line adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine only (1000 mg/m2). He was disease free for 2 years. Subsequently, brain metastases occurred and in February 2014 he died (Table 1).

Discussion

Overall median survival in metastatic lung cancer is very poor. In recent studies it ranged between 3 and 12 months, depending on type of treatment [8]. Peritoneal metastases from extra-abdominal cancers are rare and have a poor prognosis. In a recent large population study by Flanagan et al., the overall incidence rate of peritoneal metastases from extra-abdominal cancers was 9%, mostly originating from breast cancer (40.8%), followed by lung cancer (25.6%), and melanoma (9.5%) [5]. Satoh et al. reported a rate of 1.2% of peritoneal metastases complicating the clinical course of advanced lung cancer [9], while in other autopsy series this rate was found to be 12% [10]. Therefore, it could be argued that a number of cases of peritoneal metastases remains undiagnosed or unreported in patients with lung cancer. A few studies reported isolated bowel metastases from non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) with very poor prognosis [4, 9, 10] and some others described the peritoneal diffusion of pleural mesothelioma [11, 12].

In gastrointestinal tumors, peritoneal metastases generally arise either from direct invasion of the bowel wall or from cancer cells spilled by surgical manipulation [13]. These mechanisms are not applicable to lung cancer. In stage IV lung cancer, pleural metastases at diagnosis are significantly associated with subsequent peritoneal spread, whereas no association between oncogene status and peritoneal disease has been reported [6]. Pleural serosa infiltration might eventually explain the peritoneal seeding, but this mechanism could not be considered in our cases since our patients had no pleural disease.

According to the two most recent systematic reviews, bowel obstruction is the most frequent clinical presentation although bleeding and perforation are also reported [14, 15]. CT and positron emission tomography (PET) scans are useful tools for diagnosis in the late stages, while CT scan sensitivity is low at the early stage of peritoneal diffusion. In most patients, the time interval between primary lung cancer and peritoneal metastases ranges from 2 months to 4 years. The most frequent histology is NSCLC, with large cell cancer and adenocarcinoma being the most common subtypes. The prognosis for patients with peritoneal metastases from lung cancer is very poor regardless of the treatment, with a median survival rate of 2 to 4 months. In a recent review, Balla et al. found two cases of peritoneal metastases out of a sample of 91 patients with lung cancer with gastrointestinal metastases: the disparity with autopsy series suggests that most cases are asymptomatic or unreported [16, 17]. Emergency surgery for bowel obstruction and extra-abdominal metastases, found in up to 60% of patients [11, 12], could be the main reasons for the poor prognosis. However, the patients reported in this study had an unexpected good outcome despite their emergency presentation and the presence of diffused peritoneal involvement in one of them. They reached, respectively, 3-year and 2-year disease-free survival and one of them is currently alive. The absence of extra-abdominal metastases might perhaps explain the unexpected long survival. However, our results suggest that a combined approach (surgery and chemotherapy) could be advocated in selected patients with peritoneal metastases from lung cancer with some survival advantages compared to standard treatment. Cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in unconventional indications is occasionally reported in experienced tertiary centers [2], most frequently from rare ovarian cancers, sarcoma, or neuroendocrine tumors, and, more rarely, from gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma and desmoplastic small round cell tumors. The gap existing between the small reported series data and the incidence rates in autopsy series could suggest that in most cases peritoneal metastases from lung cancer remain clinically silent [16]. Our results on these two patients might help in stimulating more awareness of this condition and in suggesting a strict follow-up: in fact, early diagnosis of peritoneal diffusion, which is probably often underrated, could allow a radical cytoreductive surgery providing some advantages to survival.

Considering the behavior of lung cancer, in particular, its tendency to early metastases because of its continuous dynamic state and large blood and lymphatic supply that spreads a large amount of neoplastic cells directly in the bloodstream [18], the association of a strict follow-up and focused imaging techniques could help to identify selected cases to be treated, avoiding emergency “salvage” treatments that are difficult to perform even in dedicated centers.

High postoperative morbidity should be carefully considered when an extensive surgical treatment is planned on a patient with an advanced oncological stage. In our small series of two patients no major complications were observed, and maximal cytoreduction and HIPEC should not be discarded a priori as a treatment option. Further studies on this specific subset of patients could better clarify indications and limits.

Conclusions

In our patients with isolated peritoneal metastases from lung cancer, cytoreduction showed good prognosis with acceptable morbidity. Although resection is the standard of care in bowel obstructions, this treatment option might be considered even in an elective stetting in highly selected cases to improve survival. Strict clinical and imaging diagnostic follow-up should be performed in these patients, and a peritoneal diffusion of the tumor should be anticipated and investigated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CCS:

-

Completeness of cytoreduction score

- CDX2:

-

Caudal type homeobox transcription factor 2

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CYFRA 21-1:

-

Cytokeratin-19 fragment

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncologic Group

- GIST:

-

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

- HIPEC:

-

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy

- HMB-45:

-

Human melanoma black 45

- MART-1:

-

Melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung carcinoma

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

- TTF-1:

-

Thyroid transcription factor 1

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

References

Sugarbaker PH. Prevention and treatment of peritoneal metastases: a comprehensive review. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2019;10:3–23.

Goéré D, Passot G, Gelli M, Levine EA, Bartlett DL, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Complete cytoreductive surgery plus HIPEC for peritoneal metastases from unusual cancer sites of origin: results from a worldwide analysis issue of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI). Int J Hyperth. 2017;33:520–7.

Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Fallah M, Thomsen H, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, et al. Metastatic sites and survival in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86(1):78–84.

Abbate MI, Cortinovis DL, Tiseo M, Vavalà T, Cerea G, Toschi L, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in non-small-cell lung cancer: retrospective multicentric analysis and literature review. Future Oncol. 2019;15(9):989–94.

Flanagan M, Solon J, Chang KH, Deady S, Moran B, Cahill R, et al. Peritoneal metastases from extra-abdominal cancer - A population-based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(11):1811–7.

Patil T, Aisner DL, Noonan SA, Bunn PA, Purcell WT, Carr LL, et al. Malignant pleural disease is highly associated with subsequent peritoneal metastasis in patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer independent of oncogene status. Lung Cancer. 2016;96:27–32.

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncologic Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55.

Socinski M, Morris D, Master GA, Lilenbaum R. American College of Chest Physicians: Chemotherapeutic management of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123:226s–43s.

Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Yamashita YT, Kurishima K, Ohtsuka M, Sekizawa K. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in lung cancer patients. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:1305–7.

Yoshimoto A, Kasahara K, Kawashima A. Gastrointestinal metastases from primary lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(18):3157–60.

Sibio S, Sammartino P, Accarpio F, Biacchi D, Cornali T, Cardi M, et al. Metastasis of pleural mesothelioma presenting as bleeding colonic polyp. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1898–901.

Iafrate F, Sibio S, Sammartino P, Ciolina M, Pichi A, Accarpio F, et al. What caused gastrointestinal bleeding in a woman with a history of pleural mesothelioma? Metastatic diffuse epithelioid mesothelioma. Gut. 2010;59(644):690.

Reis-Filho JS, Carrilho C, Valenti C, Leitão D, Ribeiro CA, Ribeiro SG, et al. Is TTF1 a good immunohistochemical marker to distinguish primary from metastatic lung adenocarcinomas? Pathol Res Pract. 2000;196(12):835–40.

Di JZ, Peng JY, Wang ZG. Prevalence, clinicopathological characteristics, treatment, and prognosis of intestinal metastasis of primary lung cancer: a comprehensive review. Surg Oncol. 2014;23:72–80.

Balla A, Subiela JD, Bollo J, Martínez C, Rodriguez LC, et al. Gastrointestinal metastasis from primary lung cancer. Case series and systematic literature review. Cir Esp. 2018;96:184–97.

Jevremovic V. Is gastrointestinal metastasis of primary lung malignancy as rare as reported in literature? A comparison between clinical cases and postmortem. Stud Oncol Hematol Rev. 2016;12:51–7.

Kim MS, Kook EH, Ahh AH, Jeon SY, Yoon JH, Han MS, et al. Gastrointestinal metastasis of lung cancer with special emphasis on a long-term survivor after operation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:297–301.

Berger A, Cellier C, Daniel C, Kron C, Riquet M, Barbier JP, et al. Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung: clinical findings and outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1884–7.

Funding

European Society of Degenerative Disease (ESDD) contributed to the study by supporting data analysis and collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS and GS designed the study and they were the surgeons who operated on the patients. BMS, SDC, MC, and ADG collected data and wrote the paper. PS critically revised and finally approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval does not apply to the present study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sibio, S., Sica, G.S., Di Carlo, S. et al. Surgical treatment of intraperitoneal metastases from lung cancer: two case reports and a review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 13, 262 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2178-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2178-5