Abstract

Background

Patients with hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures have high mortality due to delayed hemorrhage control. We hypothesized that the availability of interventional radiology (IR) for angioembolization may vary in spite of the mandated coverage at US Level I trauma centers, and that the priority treatment sequence would depend on IR availability.

Methods

This survey was designed to investigate IR availability and pelvic fracture management practices. Six email invitations were sent to 158 trauma medical directors at Level I trauma centers. Participants were allowed to skip questions and irrelevant questions were skipped; therefore, not all questions were answered by all participants. The primary outcome was the priority treatment sequence for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Predictor variables were arrival times for IR when working off-site and intervention preparation times. Kruskal-Wallis and ordinal logistic regression were used; alpha = 0.05.

Results

Forty of the 158 trauma medical directors responded to the survey (response rate: 25.3%). Roughly half of participants had 24-h on-site IR coverage, 24% (4/17) of participants reported an arrival time ≥ 31 min when IR was on-call. 46% (17/37) of participants reported an IR procedure setup time of 31–120 min. Arrival time when IR was working off-site, and intervention preparation time did not significantly affect the sequence priority of angioembolization for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures.

Conclusions

Trauma medical directors should review literature and guidelines on time to angioembolization, their arrival times for IR, and their procedural setup times for angioembolization to ensure utilization of angioembolization in an optimal sequence for patient survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

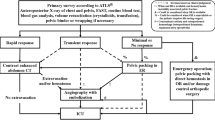

Pelvic fracture management is one of the most complex treatment strategies [1]. Published guidelines offer varying approaches to care for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures [2,3,4,5,6]. The World Society of Emergency Surgeons (WSES) and Western Trauma Association (WTA) recommend selective angioembolization after pelvic packing [2, 3]. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) and Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) suggest angioembolization after circumferential compression device application [5, 6]. Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) [4] utilizes angioembolization after external fixation and pelvic packing, or last when in extremis. There remains a high level of ambiguity on the optimal management of patients with hemodynamic unstable pelvic fractures across guidelines [2,3,4,5,6].

It is known that the time from presentation to angiography affects mortality in cases where angioembolization is needed [7]. Tanizaki et al. found a 4-fold increase in mortality rates for patients who went to angiography 60 min after arrival when compared to those who went within 60 min [7]. This is at least part of the reason that the American College of Surgeons (ACS) requires an interventional radiologist available within 30 min at Level I trauma centers [8]. Although, it has been reported that not all Level I trauma centers have IR on-site, the full extent of IR availability has not been described; therefore it is unclear if angiography within 1 h of arrival is possible [9].

Methods

This anonymous cross-sectional survey of 158 trauma medical directors at United States ACS-verified Level I trauma centers was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board. The contact list was derived from the ACS website, individual trauma center’s websites, and via telephone. To view the invitation list, view the Appendix. Coauthors piloted the web-based survey prior to its online dissemination through SurveyMonkey Inc. (San Mateo, California; www.surveymonkey.com). Six invitations, that contained the approved partial waiver of consent, were emailed from March 1, 2018 to June 26, 2018. Participants were called to verify email receipt if they had not responded upon sending the final two invitations. No compensation was provided, and participation was voluntary. Trauma medical directors or an assigned colleague completed the survey and are referred to as “participants”.

The study hypotheses were 1) that IR was not on-site and prepared for intervention within 60 min, and 2) arrival times for IR when working off-site and the time for IR to prepare for intervention would be associated with the priority treatment sequence for angioembolization. The survey included 46 questions regarding IR availability and pelvic fracture management practices. To view questions pertaining to this paper, visit: http://bit.ly/SurveyIR. Irrelevant questions were skipped based on prior responses using SurveyMonkey’s ‘skip logic’, and participants could skip any question; therefore, there are missing responses for individual questions. Analysis was completed on SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) software. Categorical data were summarized as counts and proportions. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) sequence for angioembolization was compared by both the arrival time for IR, and by the time for IR to prepare for intervention using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Ordinal logistic regression was used to determine if the arrival time for IR, or the time for IR to prepare for intervention was associated with the priority treatment sequence for angioembolization. All hypothesis tests were two-tailed with an alpha of 0.05.

Results

The response rate was 25% (40/158). Of the survey responses, 90% (36/40) completed and 10% (4/40) partially completed the survey; all responses were included. Participating Level I trauma centers’ characteristics have been reported [10]. The median (IQR) survey completion time was 11 min (8, 21). No pelvic fracture protocol was implemented at 28% (11/40) of participating Level I trauma centers (Table 1). The most common pelvic fracture guideline followed was the EAST guideline (23% [11/40]). A majority of participants preferred using angioembolization before pelvic packing (63% [17/27]). Contrast extravasation was the most common angioembolization indicator (60% [21/35]).

Fifty-four percent (20/37) of the represented Level I trauma centers had 24-h on-site IR coverage (Table 2). The remaining had on-call IR coverage; 13% (2/16) of participants reported IR was on-call for 24 h/day, and 31% (5/16) reported IR was on-call for 12 h/day. A majority (71% [12/17]) of participants reported a 21–30-min arrival time for IR when on-call. In addition to arrival times, 46% (17/37) of participants reported an IR procedure set-up time of 31–120 min. Most participants provided temporalizing stabilization through circumferential compression devices, pelvic packing, or REBOA while waiting for IR to prepare for intervention (Table 1).

We previously reported the priority treatment sequence for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures [10]. The median priority treatment sequence for angioembolization was examined according to the IR arrival time when working off-site and to the time it took IR to prepare for intervention (Table 3). There was no significant relationship between the arrival times, or the intervention preparation time, and median priority sequence of angioembolization. The intervention preparation time, and the arrival time for IR when working off-site, were not significant predictors for the priority treatment sequence of angioembolization, (Table 4). This is evidenced by a lack of significance for these variables as well as a lack of significance in the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit p-value.

Discussion

This study surveyed 25% of ACS-verified Level I trauma centers on angiography practices and IR availability to treat hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. We failed to reject the null hypotheses; IR availability was variable across Level I trauma centers and did not significantly affect the priority treatment sequence of angioembolization. A majority of participants utilized angioembolization and pelvic packing, supporting the argument that pelvic packing and angioembolization should be complementary, not competitive, as the treatments target either venous or arterial hemorrhages [11]. Angioembolization primarily treats arterial bleeds, representing 10–20% of hemorrhaging, but cannot treat the majority of hemorrhaging from venous and cancellous sources [2]. Although the priority sequence for angioembolization and pelvic packing continues to be debated, this study observed a reported preference.

The majority of participants used angioembolization before pelvic packing. Contrary to this, it has been suggested that pelvic packing may be more efficient when used before angioembolization as it treats the majority of pelvic hemorrhaging [2]. Predicting the need for angioembolization has proven difficult; applying pelvic packing first allows for identification of the bleed source and determination of the need for angioembolization [3, 9, 11,12,13]. Additionally, several studies found a shorter time from admission to pelvic packing than angiography [13,14,15,16]. The use of angioembolization before pelvic packing may be due to EAST guideline, being the most commonly followed guideline, recommending angioembolization first [5]. Although Cothren et al. [17] stated preperitoneal pelvic packing can supplant angioembolization needs, this study found that most participants utilized angioembolization and prioritized it earlier than other treatment modalities.

It is our observation that a common reason for pelvic packing application is due to excessive wait times for IR. Despite the prevalence of angioembolization before pelvic packing, roughly half of the responding Level I trauma centers did not have 24-h on-site IR coverage. Furthermore, many participants reported arrival and IR procedure preparation times in excess of 30 min; some as long as 1–2 h. Ironically, this study revealed a lack of association between the amount of time it took IR to prepare for intervention and the priority treatment sequence of angioembolization for patients with hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Yet, all participants reported utilization of alternative treatments while IR prepared for intervention. Not surprisingly, circumferential compression device was the most common treatment utilized while waiting; which is non-invasive and easily applied [2]. Pelvic packing was also a common treatment modality utilized while IR prepared; a sequence described by Burlew et al. [9] Almost half the participants indicated REBOA was utilized while IR prepared for intervention, suggesting more widespread use than previously reported [18]. The variety of treatment modalities used while waiting is no surprise, given that no guideline provides direction in this situation [2,3,4,5,6]. Therefore, more data is needed to determine the optimal priority treatment when IR is not prepared for intervention.

Limitations

The response rate of 25% was a limitation as the participants responses may not be representative of all Level I trauma centers. The online-only survey format may have negatively impacted the response rate as some trauma medical directors noted a preference towards paper surveys. Some Level I trauma centers had outdated contact information for the trauma medical director which resulted in less email invitations being sent to the participant. Responses may have been subject to self-report and recall biases. Survey anonymity and instructions to have protocols on-hand were precautions to reduce these biases. In addition, mortality data was not collected; therefore we cannot conclude what practices were associated with better outcomes.

Conclusions

The optimal priority treatment sequence for pelvic fractures has not been definitively determined. The reported IR arrival time and time to prepare for intervention did not significantly predict the priority treatment sequence of angioembolization; suggesting the priority treatment sequence was not altered based on these timing metrics. The use of angioembolization first may only be viable to prevent mortality at centers with 24-h on-site IR availability or faster preparation times. Level I trauma centers should review the literature and guidelines on time to angioembolization, their own arrival times for interventional radiology when working off-site, and their intervention preparation times for angioembolization to ensure utilization of the treatment options in an optimal sequence for patient survival.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study is stored on Sharefile, an electronic HIPAA and HITECH-compliant platform that ensures all transmissions are fully encrypted, end-to-end. The datasets used for analysis for the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

American College of Surgeons

- ATLS:

-

Advanced Trauma Life Support

- EAST:

-

Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma

- IR:

-

Interventional Radiology

- REBOA:

-

Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta

- TQIP:

-

Trauma Quality Improvement Program

- WSES:

-

World Society of Emergency Surgeons

- WTA:

-

Western Trauma Association

References

Stahel PF, Burlew CC, Moore EE. Current trends in the management of hemodynamically unstable pelvic ring injuries. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23:511–9.

Coccolini F, Stahel PF, Montori G, Biffl W, Horer TM, Catena F, Kluger Y, Moore EE, Peitzman AB, Ivatury R, Coimbra R, Fraga GP, Pereira B, Rizoli S, Kirkpatrick A, Leppaniemi A, Manfredi R, Magnone S, Chiara O, Solaini L, Ceresoli M, Allievi N, Arvieux C, Velmahos G, Balogh Z, Naidoo N, Weber D, Abu-Zidan F, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L. Pelvic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:1–18.

Biffl WL, Cothren CC, Moore EE, Kozar R, Cocanour C, Davis JW, McIntyre RC, West MA, Moore FA. Western trauma association critical decisions in trauma: screening for and treatment of blunt cerebrovascular injuries. J Trauma. 2009;67:1150–3.

American College of Surgeons. Best practices in the Management of Orthopaedic Trauma; 2015. p. 1–40. Available from: https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality programs/trauma/tqip/traumatic brain injury guidelines.ashx. [Accessed 7 Mar 2018]

Cullinane DC, Schiller HJ, Zielinski MD, Bilaniuk JW, Collier BR, Como J, Holevar M, Sabater EA, Sems SA, Vassy WM, Wynne JL. Eastern Association for the Surgery of trauma practice management guidelines for hemorrhage in pelvic fracture—update and systematic review. J Trauma. 2011;71:1850–68.

The American College of Surgeons. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): the ninth edition. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2013.

Tanizaki S, Maeda S, Matano H, Sera M, Nagai H, Ishida H. Time to pelvic embolization for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures may affect the survival for delays up to 60 min. Injury. 2014;45:738–41 Elsevier Ltd.

The American College of Surgeons. In: Rotondo MF, Cribara C, Smith RS, editors. Resources for optimal care of the injured patient. 6th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2014.

Burlew CC, Moore EE, Smith WR, Johnson JL, Biffl WL, Barnett CC, Stahel PF. Preperitoneal pelvic packing/external fixation with secondary angioembolization: optimal care for life-threatening hemorrhage from unstable pelvic fractures. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:628–35 Elsevier Inc.

Blondeau B, Orlando A, Jarvis S, Banton K, Berg GM, Patel N, Meinig R, Tanner A, Carrick M, Bar-Or D. Variability in pelvic packing practices for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures at US level 1 trauma centers. Patient Saf Surg. 2019;13:1–10.

Suzuki T, Smith WR, Moore EE. Pelvic packing or angiography: competitive or complementary? Injury. 2009;40:343–53.

Smith WR, Moore EE, Osborn P, Agudelo JF, Morgan SJ, Parekh AA, Cothren C. Retroperitoneal packing as a resuscitation technique for hemodynamically unstable patients with pelvic fractures: report of two representative cases and a description of technique. J Trauma. 2005;59:1510–4.

Burlew CC, Moore EE, Stahel PF, Geddes AE, Wagenaar AE, Pieracci FM, Fox CJ, Campion EM, Johnson JL, Mauffrey C. Preperitoneal pelvic packing reduces mortality in patients with life-threatening hemorrhage due to unstable pelvic fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82:233–42.

Tai DKC, Li W-H, Lee K-Y, Cheng M, Lee K-B, Tang L-F, Lai AK-H, Ho H-F, Cheung M-T. Retroperitoneal pelvic packing in the Management of Hemodynamically Unstable Pelvic Fractures: a level I trauma center experience. J Trauma. 2011;71:E79–86.

Osborn PM, Smith WR, Moore EE, Cothren CC, Morgan SJ, Williams AE, Stahel PF. Direct retroperitoneal pelvic packing versus pelvic angiography: a comparison of two management protocols for haemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures. Injury. 2009;40:54–60.

Li Q, Dong J, Yang Y, Wang G, Wang Y, Liu P, Robinson Y, Zhou D. Retroperitoneal packing or angioembolization for haemorrhage control of pelvic fractures - quasi-randomized clinical trial of 56 haemodynamically unstable patients with injury severity score ≥33. Injury. 2016;47:395–401 Elsevier Ltd.

Cothren CC, Osborn PM, Moore EE, Morgan SJ, Johnson JL, Smith WR. Preperitonal pelvic packing for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures: a paradigm shift. J Trauma. 2007;62:834–42.

Stannard A, Eliason JL, Rasmussen TE. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) as an adjunct for hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2011;71:1869–72.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participating Trauma Medical Directors who shared their time, experience, and protocol information for this survey.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ contributed to conception and study design, acquisition of data, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted and revised the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. AO contributed to conception and study design, critically revised manuscript, provided final approval of the manuscript submitted, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. BB, KB, CR, GB, NP, MK, MC, and DBO contributed to conception and study design, interpreted the data, critically revised manuscript, provided final approval of the manuscript submitted. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Western Institutional Review Board, IRB Study No: 1183667. Western Institutional Review Board Multiple Project Assurance Number: IRB00000533.

The study was approved with a partial waiver of consent, waiving the requirement for a conform containing a signature of the participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Level I Trauma Centers Invited to Participate in the Survey

Albany Medical Center | |

Banner University Medical Center – Tucson | |

Banner University Medical Center Phoenix | |

Barnes-Jewish Hospital | |

Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas | |

Baystate Medical Center | |

Beaumont Hospital - Royal Oak Campus | |

Bellevue Hospital Center | |

Ben Taub Hospital - Harris Health System | |

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center | |

Boston Medical Center | |

Brigham and Women’s Hospital | |

Bronson Methodist Hospital | |

Brooke Army Medical Center | |

Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital | |

Carolinas Medical Center | |

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center | |

Charleston Area Medical Center | |

Christiana Care Health System | |

Cleveland Clinic Akron General | |

Community Regional Medical Center | |

Cooper University Health Care | |

Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center | |

Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas | |

Denver Health Medical Center | |

Detroit Receiving Hospital | |

Dignity Health Chandler Regional Medical Center | |

Dignity Health St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center | |

Duke University Hospital | |

East Texas Medical Center Tyler | |

Erie County Medical Center | |

Eskenazi Health | |

Froedtert Hospital | |

George Washington University Hospital | |

Grady Memorial Hospital | |

Grant Medical Center | |

Greenville Memorial Hospital | |

Harbor UCLA Medical Center | |

Hartford Hospital | |

Hennepin County Medical Center | |

Henry Ford Hospital | |

Highland Hospital/A member of Alameda Health System | |

HonorHealth John C. Lincoln Medical Center | |

HonorHealth Scottsdale Osborn Medical Center | |

Howard University Hospital | |

Hurley Medical Center | |

Indiana University Health Methodist Hospital | |

Inova Fairfax Hospital | |

Intermountain Medical Center | |

Iowa Methodist Medical Center | |

Jackson Memorial Hospital | |

Jacobi Medical Center | |

Jamaica Hospital Medical Center | |

JPS Health Network | |

Kendall Regional Medical Center | |

LAC + USC Medical Center | |

Legacy Emanuel Medical Center | |

Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center | |

Loyola University Medical Center | |

Maine Medical Center | |

Maricopa Integrated Health System - Maricopa Medical Center | |

Massachusetts General Hospital | |

Mayo Clinic Rochester Trauma Centers | |

Medical Center Navient Health | |

Medical University of South Carolina | |

MedStar Washington Hospital Center | |

Memorial Hermann Hospital System – Houston | |

Memorial Regional Hospital | |

Mercy Health - St. Elizabeth Youngstown Hospital | |

Mercy Health - St. Vincent Medical Center | |

Methodist Dallas Medical Center | |

MetroHealth Medical Center | |

Miami Valley Hospital | |

Morristown Medical Center | |

Nassau University Medical Center | |

Nebraska Medicine - Nebraska Medical Center | |

New Jersey Trauma Center at the University Hospital | |

New York Presbyterian Hospital - Weill Cornell Medical Center | |

New York-Presbyterian – Queens | |

North Memorial Health Hospital | |

Northwell Health North Shore University Hospital | |

Northwell Health Staten Island University Hospital | |

NYC Health and Hospitals - Elmhurst | |

NYC Health and Hospitals - Kings County | |

NYU Langone Hospital – Brooklyn | |

NYU Winthrop Hospital | |

Oregon Health & Science University | |

OU Medical Center | |

Palmetto Health Richland | |

Parkland Health & Hospital System | |

Penrose Hospital | |

ProMedica Toledo Hospital | |

Regions Hospital | |

Rhode Island Hospital | |

Richmond University Medical Center | |

Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital | |

Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center | |

Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital | |

Santa Clara Valley Medical Center | |

Scott & White Memorial Hospital – Temple | |

Scripps Mercy Hospital | |

Sparrow Hospital | |

Spectrum Health - Butterworth Hospital | |

SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital | |

St. Anthony Hospital | |

St. Joseph Mercy Hospital - Ann Arbor | |

St. Vincent Indianapolis Hospital | |

Stanford Health Care | |

Stony Brook Medicine | |

Summa Akron City Hospital | |

Swedish Medical Center | |

Tampa General Hospital | |

The Medical Center of Plano | |

The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center | |

The Queen’s Medical Center | |

The University of Kansas Hospital | |

The University of Toledo Medical Center | |

Tufts Medical Center | |

UC Irvine Health | |

UC San Diego Medical Center | |

UMASS Memorial Medical Center | |

University Health System - San Antonio | |

University Health-Shreveport | |

University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center | |

University Medical Center – Lubbock | |

University Medical Center New Orleans | |

University Medical Center of El Paso | |

University Medical Center of Southern Nevada | |

University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital | |

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences | |

University of California, Davis Medical Center | |

University of Cincinnati Medical Center | |

University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics | |

University of Kentucky Albert B. Chandler Hospital | |

University of Louisville Hospital | |

University of Michigan Health System | |

University of Missouri Health System | |

University of New Mexico Hospital | |

University of North Carolina Hospital | |

University of Rochester Medical Center/Strong Memorial Hospital | |

University of Tennessee Medical Center | |

University of Texas Medical Branch | |

University of Utah Health Care | |

University of Vermont Medical Center | |

University of Virginia Health System | |

University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics Authority | |

Upstate University Hospital | |

Vanderbilt University Medical Center | |

Via Christi Hospitals – Wichita | |

Vidant Medical Center | |

Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center | |

Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center | |

WakeMed Health & Hospitals | |

Wesley Medical Center | |

West Virginia University Hospitals-J.W. Ruby Memorial Hospital | |

Westchester Medical Center | |

Yale-New Haven Hospital | |

Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jarvis, S., Orlando, A., Blondeau, B. et al. Variability in the timeliness of interventional radiology availability for angioembolization of hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures: a prospective survey among U.S. level I trauma centers. Patient Saf Surg 13, 23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-019-0201-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13037-019-0201-9