Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 12-item survey (WHODAS-12) is a questionnaire developed by the WHO to measure functioning across health conditions, cultures, and settings. WHODAS-12 consists of a subset of the 36 items of WHODAS-2.0 36-item questionnaire. Little is known about the minimal important difference (MID) of WHODAS-12 in persons with chronic low back pain (LBP), which would be useful to determine whether rehabilitation improves functioning to an extent that is meaningful for people experiencing the condition. Our objective was to estimate an anchor-based MID for WHODAS-12 questionnaire in persons with chronic LBP.

Methods

We analyzed data from two cohort studies (identified in our previous systematic review) conducted in Europe that measured functioning using the WHODAS-36 in adults with chronic LBP. Eligible participants were adults with chronic LBP with scores on another measure as an anchor to indicate participants with small but important changes in functioning over time [Short-form-36 Physical Functioning (SF36-PF) or Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)] at baseline and follow-up (study 1: 3-months post-treatment; study 2: 1-month post-discharge from hospital). WHODAS-12 scores were constructed as sums of the 12 items (scored 0–4), with possible scores ranging from 0 to 48. We calculated the mean WHODAS-12 score in participants who achieved a small but meaningful improvement on SF36-PF or ODI at follow-up. A meaningful improvement was an MID of 4–16 on ODI or 5–16 on SF36-PF.

Results

Of 70 eligible participants in study 1 (mean age = 54.1 years, SD = 14.7; 69% female), 18 achieved a small meaningful improvement based on SF-36 PF. Corresponding mean WHODAS-12 change score was − 3.22/48 (95% CI -4.79 to -1.64). Of 89 eligible participants in study 2 (mean age = 65.5 years, SD = 11.5; 61% female), 50 achieved a small meaningful improvement based on ODI. Corresponding mean WHODAS-12 change score was − 5.99/48 (95% CI − 7.20 to -4.79).

Conclusions

Using an anchor-based approach, the MID of WHODAS-12 is estimated at -3.22 (95% CI -4.79 to -1.64) or -5.99 (95% CI − 7.20 to -4.79) in adults with chronic LBP. These MID values inform the utility of WHODAS-12 in measuring functioning to determine whether rehabilitation or other health services achieve a minimal difference that is meaningful to patients with chronic LBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

At least one in three people globally will require rehabilitation at some point in their life [1], and rehabilitation needs will increase over time [2]. However, this increasing need for rehabilitation is largely unmet [2]; consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a call to increase access to rehabilitation services globally through strengthening health systems for rehabilitation [3]. Low back pain (LBP) is the main reason for unmet rehabilitation needs globally [1, 4]. It is thus critically important that people with LBP receive rehabilitation services to improve functioning and health outcomes.

To understand the utility of rehabilitation care, it is important to measure whether the delivery of rehabilitation services effectively improves functioning at individual and population levels. WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS) is a self-reported questionnaire developed by the WHO as a generic tool that integrates an individual’s level of functioning in major life domains, directly linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health [5]. WHODAS is applicable across various cultures and settings, and easy to administer in clinical and population-based settings [5]. To assess whether rehabilitation is effective, it is useful to determine whether receiving rehabilitation services achieves the minimal important difference (MID). However, little is known on the MID of WHODAS-12 in persons with chronic LBP.

We conducted a systematic review [6] on the psychometric properties of the WHODAS and identified one study reporting MIDs for the WHODAS-12 in patients with musculoskeletal conditions [7]. Specifically, in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain (including LBP) in Finland, MID of WHODAS-12 was estimated as a range of 3.09 to 4.68 out of 48 using distribution-based methods [7]. More studies are needed to estimate the MID of WHODAS-12 in persons with chronic LBP, particularly using anchor-based methods by considering important differences in other outcome measures (e.g., global perceived recovery) to facilitate triangulation from multiple anchors/methods. COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) recommends using an anchor-based longitudinal approach to determine MID to reflect what patients consider important, rather than distribution-based methods which often uses standard deviation as the metric related to pre-treatment variability in the measure [8].

Our systematic review [6] identified two longitudinal studies that examined the measurement properties of WHODAS-36 in persons with chronic LBP [9, 10]. Since specific WHODAS-36 questions can be used to compute WHODAS-12 scores, we proposed secondary use of data from these two original studies to estimate the MID of WHODAS-12 in persons with chronic LBP. Therefore, our objective was to compute an anchor-based MID for the WHODAS-12 questionnaire in persons with chronic LBP.

Methods

We analyzed data from two cohort studies that measured functioning using WHODAS-36 in adults with chronic LBP [9, 10] at two points in time. This project has been approved by the Research Ethics Board at Ontario Tech University (Reference #17173).

We selected these two studies based on our previous systematic review [6]. Our systematic review examined the measurement properties and minimal important difference of the 36-item and 12-item WHODAS questionnaire in persons with LBP. This systematic review identified only one cross-sectional study that estimated the MID of WHODAS-12 in this population using distribution-based methods. The systematic review also identified two longitudinal studies with WHODAS-36 data that could convert to WHODAS-12 scores and estimate MID using an anchor-based approach, which are the two studies included in this analysis [9, 10]. Based on critical appraisal using COSMIN and COSMIN-OMERACT checklists in the systematic review, the study by Cwirlej-Sozanska et al. was deemed very good for internal consistency, adequate for reliability, doubtful for construct validity, and doubtful for responsiveness; the study by Garin et al. was deemed doubtful for construct validity [6].

Study sample

Eligible participants were adults with chronic LBP who completed WHODAS and another measure that could be used as an anchor to identify subjects experiencing a small but important change in functioning between the two measurement points. The anchor measures that we used were the Short-form-36 Physical Functioning dimension (SF-36 PF) in study 1 [9] and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) in study 2 [10]. These were selected as they measure closely related constructs to that of the WHODAS-12. Study 1 by Garin et al. included adults aged ≥ 18 years with different chronic conditions recruited from seven European Centres in Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, and Spain [9]. Chronic LBP was defined as ≥ 12 weeks’ duration in this study. The original sample in study 1 had a mean age of 52.7 years (SD 15.6), 56.2% were female, and the mean score on the 36-item WHODAS was 24.8 (SD 19.3); 9.9% of the entire sample had LBP. Evaluations were made at baseline (pre-treatment), six weeks, and three months. For our study, we restricted to participants with chronic LBP and focused on data from baseline and 3-month follow-up, as 3-month follow-up was originally intended to assess responsiveness of WHODAS-36. Study 2 by Cwirlej-Sozanska et al. included patients (aged ≥ 50 years) with chronic LBP (≥ 12 weeks’ duration) admitted to the rehabilitation ward of a family specialist hospital in Poland [10]. Exclusion criteria were severe neurological disorders of the central nervous system (stroke and traumatic brain injury), unstable cardiovascular diseases, active cancer, and amputations. The original sample in study 2 had a mean age of 66 years (SD 11.6), 62.0% were female, and mean score on the 36-item WHODAS was 41.5 (SD 13.8). Evaluations were at baseline (admission), two days post-admission, and one month after completion of rehabilitation in the hospital. For our study, we focused on data from baseline and 1-month post-discharge from hospital to compute an MID for WHODAS-12. Further details of each study are described in the original articles [9, 10].

WHO Disability Assessment Schedule

WHODAS 2.0 is a generic, self-reported assessment instrument developed by the WHO to provide a standardized method for measuring functioning across health conditions, cultures, and settings [5]. The short version of the WHODAS 2.0, WHODAS-12, has 12 questions rated from 0 (no difficulty) to 4 (extreme difficulty/cannot do), which are a subset of the 36 questions from the full version (WHODAS-36) (see Additional File 1) [5], with two questions from each of the six domains: (1) Cognition (items 3, 6); (2) Mobility (items 1, 7); (3) Self-care (items 8, 9); (4) Getting along (items 10, 11); (5) Life activities (items 2, 12); and (6) Participation (items 4, 5) [5]. Since the original data from studies 1 and 2 had WHODAS-36 questions and scores, the WHODAS-12 could be constructed from the specific WHODAS-12 questions. Simple scoring involves adding up the scores from each WHODAS-12 item to compute a summary score out of 48 (higher scores mean greater limitations in functioning) [5]. As measured using WHODAS-12, we viewed disability and functioning as opposite ends of the same spectrum; high disability represents low functioning (or limitations in functioning) and low disability represents high functioning. In chronic LBP, WHODAS-36 has adequate content validity, structural validity, internal consistency, and reliability, and WHODAS-12 has adequate structural validity and internal consistency [6]. Scores from the short and full versions of WHODAS 2.0 are highly correlated [11, 12]. If questionnaires were missing only one item, WHODAS-12 scores based on a sum of the non-missing items, rescaled to maintain range from 0 to 48 can be used according to the WHODAS 2.0 manual [5]. We applied this rule when the work item was missing, as it was the most frequently missing item.

Anchor measures and minimal important difference

We used change in the SF-36 PF in study 1 and change in the ODI in study 2 as anchor measures to identify subjects experiencing small but important improvements in functioning over time. The SF-36 questionnaire is a generic 36-item questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life [13]. It includes eight individual dimensions, including physical functioning (SF-36 PF). SF-36 PF is composed of 10 items with a 3-point rating scale (higher scores indicate better health status). The SF-36 questionnaire has adequate validity, reliability, and responsiveness in persons with musculoskeletal conditions [14,15,16,17]. The ODI is a questionnaire that measures functional limitations specific to back pain [18]. The questionnaire has 10 questions and is scored 0-100 (higher scores indicate higher disability). The ODI has adequate validity and reliability in persons with LBP [19, 20]. Informed by literature, a small but meaningful improvement was defined as MID of 5–16 on SF-36 PF [21,22,23] or 4–16 on the ODI [21, 24,25,26,27,28,29]; these MID ranges for SF-36 PF and ODI were identified based on previous literature focused on persons with LBP. For study 1, subjects whose scores on the SF-36 PF improved between 5 and 16 points inclusive were deemed to have experienced a small but important improvement in functioning and for study 2, subjects whose ODI scores improved between 4 and 16 points inclusive were deemed to have experienced a small but important improvement in functioning.

Analysis

We estimated WHODAS-12 scores at baseline and follow-up utilizing individual scores of the stated WHODAS-36 items, which are specific questions common to both short and full versions. Among participants who improved and achieved the minimal important difference on SF-36 PF (MID 5–16) or ODI (MID 4–16), we calculated the corresponding mean change and 95% confidence interval on WHODAS-12. The analysis for this study was generated using SAS software v9.4. (Copyright © 2012–2018, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.)

Results

Sample characteristics

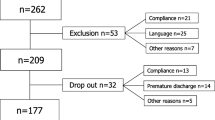

Of 108 participants with chronic LBP in study 1 (Garin et al.) [9], 70 had SF-36 PF scores at baseline and follow-up, and thus are eligible for our study. Of those, 23 had improvements in SF-36 PF scores between 5 and 16 points, of which 18 had WHODAS-12 change scores. Of 92 participants with chronic LBP in study 2 (Cwirlej-Sozanska et al.) [10], 89 had ODI scores at baseline and follow-up to be eligible for our study. Of those, 62 had improvement in ODI scores between 4 and 16 points, of which 50 had WHODAS-12 change scores.

Among patients with chronic LBP (with baseline and follow-up SF-36 PF scores) in study 1, mean age was 54.1 years (SD 14.7) and 68.6% were female (Table 1). Most were married (59.4%) and had highest education attainment levels of completing primary or secondary school (47.0%), high school (19.7%), or college/university (31.8%). The mean baseline SF-36 PF score was 64.1 (SD 25.0) and mean baseline WHODAS-12 score was 15.6 (SD 5.6) (Additional File 2 A).

Among patients with chronic LBP (with baseline and follow-up ODI scores) in study 2, mean age was 65.5 years (SD 11.5), and 60.7% were female (Table 2). More than half (52.8%) were from the countryside, and 61.8% had secondary or higher education. Mean baseline ODI score was 29.4 (SD 6.3) and mean baseline WHODAS-12 score was 19.1 (SD 6.7) (Additional File 2B).

Minimal important difference of WHODAS-12

Of 70 eligible participants in study 1 (Garin in et al.) [9], 18 achieved a small meaningful improvement based on SF-36 PF and had WHODAS-12 change scores in the data. The corresponding mean WHODAS-12 change score was − 3.22/48 (95% CI -4.79 to -1.64; minimum − 10.00, maximum 2.18). Of 89 eligible participants in study 2 (Cwirlej-Sozanska et al.) [10], 50 achieved a small meaningful improvement based on ODI and had WHODAS-12 change scores in the data. The corresponding mean WHODAS-12 change score was − 5.99/48 (95% CI − 7.20 to -4.79; minimum − 16.36, maximum 2.18).

Discussion

We estimated an MID of WHODAS-12 of -3.22/48 (95% CI -4.79 to -1.64) from one study and − 5.99/48 (95% CI -7.20 to -4.79) from another study in adults with chronic LBP. The MIDs of WHODAS-12 were calculated using an anchor-based approach by considering the achievement of MID threshold improvements on SF-36 PF and ODI. Our study advances knowledge in this area by providing MID estimates for WHODAS-12 specific to persons with chronic LBP.

Our findings on MID for WHODAS-12 in persons with chronic LBP are similar to those of the previous study in Finland in patients with musculoskeletal conditions (including LBP) [7]. Katajapuu et al. estimated MIDs of WHODAS-12 as 3.09/48 (using 0.33xSD), 3.10/48 (using standard error of the mean), and 4.68/48 (using 0.5xSD), calculated using distribution-based methods [7]. Our findings are based on an anchor-based approach using WHODAS-12 change scores to compute the MID specific to chronic LBP instead of distribution-based methods, which are based on baseline measures of WHODAS-12 only. Anchor-based approaches take into account the patient perspective of the minimal difference that is clinically important to them and also utilize change in the WHODAS-12 measured at two points in time. This is an added strength to our findings to advance knowledge in this area, as anchor-based methods are recommended based on COSMIN [8]; notably, further to anchor-based methods, triangulation of multiple methods (based on consensus, anchor-based, and distribution approaches) may be most informative for estimating the MID for WHODAS-12 [30].

Our findings of MIDs − 3.22 and − 5.99 suggest variability in this threshold of important benefit. This is aligned with MIDs estimated for other outcome measures, such as those used in our study. This includes MIDs ranging from 5 to 16 for SF-36 PF [21,22,23] and MIDs ranging from 4 to 16 for ODI [21, 24,25,26,27,28,29] in persons with LBP as informed by literature. Some variability in MIDs (e.g., MIDs in WHODAS, SF-36, ODI, or other instruments) is attributable to context and patient characteristics, such as time periods of change, severity at baseline, and anchors used [31]. Informed by previous literature on methodology and credibility of estimating MIDs [32, 33], the MID of -5.99/48 calculated from study 2 (Cwirlej-Sozanska et al.) may be the more robust estimate for two main reasons. The anchor of ODI in study 2 more closely reflects the constructs captured in WHODAS. The ODI focuses on LBP-related limitations in functioning, while the WHODAS captures limitations in functioning more broadly (i.e., not specific to LBP). Although there is overlap, the SF-36 focuses on health-related quality of life, which is a different construct from limitations in functioning. In addition, the sample in study 2 is larger and has less missing data, allowing for more precision of the WHODAS-12 MID estimate. When using this questionnaire to measure functioning, it is noted that there are potential floor effects with WHODAS-12 summary scores. In a study by Katajapuu et al., a significant floor effect (set at > 15%) was observed for WHODAS-12 summary scores using simple scoring, but no ceiling effects were observed in persons with chronic musculoskeletal conditions [34].

Our findings have potential implications for measuring functioning for chronic LBP related to rehabilitation services. To determine whether the delivery of rehabilitation is meaningful for patients, we need to assess whether rehabilitation achieves a threshold of important benefit. Health care providers can use WHODAS-12 to measure functioning and assess for achieving MID in patients. This helps to guide management and effective rehabilitation care using WHODAS-12 as an outcome measure. Moreover, our findings may inform sample size considerations for future RCTs focused on measuring functioning in samples with chronic LBP. Multiple methods may be used to inform the estimation of MID [30], so our findings can be one part of broader considerations in calculating sample size in these future studies.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has strengths. We analyzed data from two cohort studies conducted in Europe to compute two estimates of MID for WHODAS-12 in adults with chronic LBP. Notably, we used an anchor-based approach to account for those who achieved a minimal difference that was clinically important to patients on SF-36 PF or ODI. We selected MIDs for SF-36 PF and ODI in persons with LBP based on previous literature. In addition, the questionnaires WHODAS 2.0, SF-36 Health Survey, and ODI have adequate validity and reliability in persons with back pain or musculoskeletal conditions [6, 14,15,16,17, 19, 20].

Our study has limitations. First, there is potential selection bias due to missing data. In the study by Garin et al [9], 40 out of 118 participants were missing data on SF-36 PF. In the study by Cwirlej-Sozanska et al [10], 3 out of 92 participants were missing data on the ODI. Our findings are limited by small samples of the two studies and missing data, which leads to imprecision of the MID estimates that we calculated. In study 1, the participants who stayed in versus dropped out are different across various characteristics; those who dropped out tended to have the following characteristics: male, lived alone, smoker, younger, higher levels of disability and pain, lower physical function/component of health-related quality of life, and higher mental component of health-related quality of life [9] (see Additional File 3). These demonstrate that the data is not missing completely at random. While there is no way to be sure, these differences lead us to be wary of assuming that they are missing at random. The reasons for these missing data in the original cohort study by Garin et al. are not known. Second, it is important to consider that MIDs may vary by contexts to inform the generalizability of our findings. Literature suggests that MIDs may vary depending on characteristics of the study population (which can include baseline severity on measure of interest), duration of follow-up and type of intervention [31]. Therefore, knowledge users looking to use MID estimates for WHODAS-12 in persons with chronic LBP should consider whether these factors underlying our MID estimates are similar to the contexts in which they would like to apply the WHODAS MID estimates.

Conclusion

Using an anchor-based approach, the MID of WHODAS-12 is estimated at -3.22/48 (95% CI -4.79 to -1.64) or -5.99/48 (95% CI − 7.20 to -4.79) in persons with chronic LBP. These MID values inform the utility of WHODAS-12 in measuring functioning to determine whether rehabilitation or other health services achieve a minimal difference that is meaningful to the patient. Health care providers can consider using these MID values with WHODAS-12 as an outcome measure to assess whether rehabilitation is providing important benefits to patients. Overall, findings have implications for the measurement of important benefits in functioning levels related to rehabilitation services for chronic LBP.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author of the original studies on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COSMIN:

-

COnsensus–based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- MID:

-

Minimal important difference

- ODI:

-

Oswestry Disability Index

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SF-36 PF:

-

Short Form–36 Physical Functioning

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WHODAS:

-

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule

References

Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10267):2006–17.

World Health Organization, Rehabilitation. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation (accessed June 1, 2021).

World Health Organization. Rehabilitation 2030: A Call for Action. 2017. Available at: https://www.who.int/rehabilitation/rehab-2030/en/#:~:text=Rehabilitation%202030%3A%20A%20Call%20for%20Action&text=Participants%20committed%20to%20key%20actions,enhancing%20data%20collection%20on%20rehabilitation (accessed Apr 23 2021).

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 Diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858.

World Health Organization. Measuring health and disability: manual for World Health Organization (WHO) Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0). 2012. Available at: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioningdisability-and-health/who-disabilityassessment-schedule (accessed Apr 23, 2021).

Wong JJ, DeSouza A, Hogg-Johnson S, De Groote W, Southerst D, Belchos M, et al. Measurement Properties and Minimal Important Change of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 in persons with Low Back Pain: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2023;104(2):287–301.

Katajapuu N, Heinonen A, Saltychev M. Minimal clinically important difference and minimal detectable change of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) amongst patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Clin Rehabil. 2020;34(12):1506–11.

Mokkink LB, Prinsen C, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Bouter LM, De Vet H et al. COSMIN methodology for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). User Man. 2018;78(1).

Garin O, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Almansa J, Nieto M, Chatterji S, Vilagut G, et al. Validation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule, WHODAS-2 in patients with chronic Diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:51.

Ćwirlej-Sozańska A, Bejer A, Wiśniowska-Szurlej A, Wilmowska-Pietruszyńska A, de Sire A, Spalek R, et al. Psychometric properties of the Polish Version of the 36-Item WHODAS 2.0 in patients with low back Pain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:19.

Park SH, Demetriou EA, Pepper KL, Song YJC, Thomas EE, Hickie IB, et al. Validation of the 36-item and 12-item self-report World Health Organization Disability Assessment schedule II (WHODAS-II) in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res. 2019;12(7):1101–11.

Silveira C, Souza RT, Costa ML, Parpinelli MA, Pacagnella RC, Ferreira EC, et al. Validation of the WHO Disability Assessment schedule (WHODAS 2.0) 12-item tool against the 36-item version for measuring functioning and disability associated with pregnancy and history of severe maternal morbidity. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;141(1):39–47.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr., Rogers W, Raczek AE, Lu JF. The validity and relative precision of MOS short- and long-form health status scales and Dartmouth COOP charts. Results from the Medical outcomes Study. Med Care. 1992;30(5 Suppl):Ms253–65.

Beaton DE, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C. Evaluating changes in health status: reliability and responsiveness of five generic health status measures in workers with musculoskeletal disorders. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(1):79–93.

Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Abdalla MI, Buckingham JK, Russell IT. The SF36 health survey questionnaire: an outcome measure suitable for routine use within the NHS? BMJ. 1993;306(6890):1440–4.

Haley SM, McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr. Evaluation of the MOS SF-36 physical functioning scale (PF-10): I. Unidimensionality and reproducibility of the Rasch item scale. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(6):671–84.

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr., Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–63.

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(22):2940–52. discussion 52.

Chiarotto A, Boers M, Deyo RA, Buchbinder R, Corbin TP, Costa LOP, et al. Core outcome measurement instruments for clinical trials in nonspecific low back pain. Pain. 2018;159(3):481–95.

Chiarotto A, Maxwell LJ, Terwee CB, Wells GA, Tugwell P, Ostelo RW. Roland-Morris disability questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index: which has Better Measurement Properties for Measuring Physical Functioning in nonspecific low back Pain? Systematic review and Meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2016;96(10):1620–37.

Lauridsen HH, Hartvigsen J, Manniche C, Korsholm L, Grunnet-Nilsson N. Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference for pain and disability instruments in low back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:82.

Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(17):1899–908. discussion 909.

Davidson M, Keating JL, Eyres S. A low back-specific version of the SF-36 physical functioning scale. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(5):586–94.

Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ. A comparison of a modified Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire and the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Ther. 2001;81(2):776–88.

Taylor SJ, Taylor AE, Foy MA, Fogg AJ. Responsiveness of common outcome measures for patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(17):1805–12.

Beurskens A, de Vet HCW, Köke AJA. Responsiveness of functional status in low back pain: a comparison of different instruments. Pain. 1996;65(1):71–6.

Mannion AF, Junge A, Grob D, Dvorak J, Fairbank JC. Development of a German version of the Oswestry Disability Index. Part 2: sensitivity to change after spinal Surgery. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(1):66–73.

Suarez-Almazor ME, Kendall C, Johnson JA, Skeith K, Vincent D. Use of health status measures in patients with low back pain in clinical settings. Comparison of specific, generic and preference-based instruments. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(7):783–90.

Hägg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A. The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2003;12(1):12–20.

McGlothlin AE, Lewis RJ. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA. 2014;312:1342.

Johnston BC, Ebrahim S, Carrasco-Labra A, Furukawa TA, Patrick DL, Crawford MW, et al. Minimally important difference estimates and methods: a protocol. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e007953.

Devji T, Carrasco-Labra A, Qasim A, Phillips M, Johnston BC, Devasenapathy N, et al. Evaluating the credibility of anchor based estimates of minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes: instrument development and reliability study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1714.

Wang Y, Devji T, Carrasco-Labra A, King MT, Terluin B, Terwee CB, et al. A step-by-step approach for selecting an optimal minimal important difference. BMJ. 2023;381:e073822.

Katajapuu N, Laimi K, Heinonen A, et al. Floor and ceiling effects of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Int J Rehabil Res. 2019;42:190–2.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Dorcas Beaton, PhD for helpful suggestions on methodology.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJW: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, review, and editing; SHJ: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis; writing – review and editing; WDG: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing; AC: methodology, writing – review and editing; OG: methodology, writing – review and editing; MF: methodology, writing – review and editing; APA: methodology, writing – review and editing; PC: conceptualization, methodology, writing – review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This project has been approved by the Research Ethics Board at Ontario Tech University (Reference #17173).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JJW was supported by a Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR); and reports research grants from CIHR, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), and the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation (paid to university); and travel reimbursement for teaching from Eurospine outside the submitted work. PC was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation; and reports research grants from the Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation, CIHR, College of Chiropractors of British Columbia, and World Health Organization (paid to university); payment for court testimony from the Canadian Chiropractic Protective Association and NCMIC, and travel expenses to teach from Eurospine, travel expenses to collaborate on research projects from Sophiahemmet University outside the submitted work. All remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, J.J., Hogg-Johnson, S., De Groote, W. et al. Minimal important difference of the 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS) 2.0 in persons with chronic low back pain. Chiropr Man Therap 31, 49 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-023-00521-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-023-00521-0