Abstract

Background

The diagnosis of primary headaches assists health care providers in their decision-making regarding patient treatment, co-management and further evaluation. Chiropractors are popular health care providers for those with primary headaches. The aim of this study is to examine the clinical management factors associated with chiropractors who report the use of primary headache diagnostic criteria.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was distributed between August and November 2016 to a random sample of Australian chiropractors who are members of a practice-based research network (n = 1050) who had reported ‘often’ providing treatment for patients with headache disorders to report on practitioner approaches to headache diagnosis, management, outcome measures and multidisciplinary collaboration. Multiple logistic regression was conducted to assess the factors that are associated with chiropractors who report using International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) primary headache diagnostic criteria.

Results

With a response rate of 36% (n = 381), the majority of chiropractor’s report utilising ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria (84.6%). The factors associated with chiropractors who use ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria resulting from the regression analysis include a belief that the use of ICHD primary headache criteria influences the management of patients with primary headaches (OR = 7.86; 95%CI: 3.15, 19.60); the use of soft tissue therapies to the neck/shoulders for tension headache management (OR = 4.33; 95%CI: 1.67, 11.19); a belief that primary headache diagnostic criteria are distinct for the diagnosis of primary headaches (OR = 3.64; 95%CI: 1.58, 8.39); the use of headache diaries (OR = 3.52; 95%CI: 1.41, 8.77); the use of ICHD criteria improves decision-making regarding primary headache patient referral/co-management (OR = 2.35; 95%CI: 1.01, 5.47); referral to investigate a headache red-flag (OR = 2.67; 95%CI: 1.02, 6.96) and not referring headache patients to assist headache prevention (OR = 0.16; 95%CI: 0.03, 0.80).

Conclusion

Four out of five chiropractors managing headache are engaged in the use of primary headache diagnostic criteria. This practice is likely to influence practitioner clinical decision-making around headache patient management including their co-management with other health care providers. These findings call for a closer assessment of headache characteristics of chiropractic patient populations and for further enquiry to explore the role of chiropractors within interdisciplinary primary headache management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The global adult prevalence of tension-type headache and migraine is reported to be approximately 40 and 10%, respectively [1,2,3]. These headaches constitute a substantial burden on the personal health and productivity of sufferers [4, 5] and cause a significant drain on healthcare resources [6, 7]. While those with chronic tension headache can sometimes report greater headache pain than those with migraine [8], migraine is one of the top 10 causes of years lived with disability [9] and the third leading cause of disability for those under the age of fifty [10].

Significant challenges remain regarding the management of headache patients. Headache patients are often poorly or under diagnosed [11], under treated [12, 13] or can fail to receive effective interdisciplinary management [14, 15]. Such challenges have led international headache organisations [16,17,18] and headache researchers [19, 20] to call for more effective health care service delivery for this significant patient population. While general practitioners (GPs) are typically the first point of contact for those with primary headaches [7, 21], sufferers can enter the healthcare system via a range of health care providers [22,23,24]. The use of chiropractors for headache management is likely most often for primary headaches, with studies reporting substantial use in the North America [25, 26], Australia [27] and parts of Europe [24, 28]. Despite the substantial use of chiropractors by those with primary headaches, little is known about how these practitioners manage this patient population. Such information can improve our understanding of headache-related health care delivery services and the role of these providers within the wider landscape of headache patient management.

The 3rd edition of International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) outlines the current criteria utilised for headache diagnosis [29]. Headache diagnosis is a key determinant that will influence practitioner decision-making around headache patient care. While a recent study reported the high use of headache diagnosis by chiropractors [30], there is little information regarding how primary headache diagnosis influences the clinical management of headaches by these providers. In direct response, the aim of this study was to draw upon a national sample of chiropractors to identify the headache patient management factors associated with those practitioners who utilise.

Methods

The data analysed in this study was drawn from a questionnaire distributed to members (chiropractors) of a national practice-based research network (PBRN) titled the Australian Chiropractic Research Network (ACORN) project [31]. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Technology Sydney (Approval number ETH16–0639).

Recruitment and sample

Detailed information about the ACORN PBRN recruitment and data base has been previously reported [31, 32], but briefly, ACORN recruitment was conducted via an invitation pack that included a baseline questionnaire disseminated between March and June 2015 to all registered Australian chiropractors. Invitation pack distribution was via email (with an embedded link to online questionnaire), postal distribution (hard copy questionnaire), regional chiropractic conferences (hard copy questionnaire) and the official ACORN website (with an embedded link to the online questionnaire). Forty-three percent (n = 1680) of all registered Australian chiropractors joined the ACORN network database. The socio-demographic profile of the ACORN database is representative of the wider chiropractic profession across Australia in terms of gender, age and practice location [32].

Participants for this PBRN sub-study were randomly selected from the ACORN practitioners who had reported that they ‘often’ provided treatment for patients with headache disorders in the ACORN PBRN invitation pack questionnaire. Participants were asked to complete a 31-item cross-sectional online survey between August and November 2016. An embedded link to the questionnaire was emailed to chiropractors. Three further reminders to complete the survey were sent out during the recruitment period. Participation in the survey was further promoted within routine email newsletters sent out by the Australian Chiropractors Association during that period.

Questionnaire

The introduction to the questionnaire explained the purpose, contents and approximate duration of the study and that respondent information was anonymous and survey completion voluntary. No incentives were offered to participate, and consent was implied by completing the survey. Questionnaire items specifically developed for this study aimed to examine chiropractic headache management across several clinical themes considered important to frontline headache management practice. With no validated instruments available, the key themes adopted for our study questionnaire were developed after consideration of past surveys examining the management of headache patients in primary care settings [11, 33, 34]. The survey collected information on practitioner characteristics, including gender, place of education, practice location and years in practice. Prevalence of headache in chiropractic practice was based on self-report on patient consultations over the previous two weeks. The use of formal diagnostic criteria for headaches was based on International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3 Beta) criteria [35]. The survey design included descriptions of primary headache criteria for migraine, tension-type headache and cluster headache and for secondary headache criteria for cervicogenic and medication overuse headache. The use of headache treatment outcome instruments was based on the use of the Headache Disability Index (HDI) [36], Migraine Disability Index (MIDAS) [37] and standard patient headache diaries [38]. Patient management included questions on collaboration with other healthcare providers associated with headache management (sending and receiving) and questions on the basis for patient referral. The questions on headache management provided a list of therapeutic approaches for headache including patient education on headache triggers, physical therapies and manual therapies utilised for headache (e.g. spinal manipulation, mobilisation, massage therapy).

The primary headache management questions included in the questionnaire were based upon primary headaches previously reported as most often treated by chiropractors [24, 39, 40] and after consultation with 10 practicing Australian chiropractors during survey pilot testing. The pilot testing findings were discussed between all members of the research team to assist decisions about survey duration and the selection of the survey themes and item options. This included the selection of headache treatment outcome measures, where we considered practitioner familiarity and understanding of the nature and purpose of select outcome instruments as well as treatment terminology and their views on relevance to headache management. All questionnaire items were either reported as ratings on a 4-point or 5-point Likert scale or as dichotomous (yes/no).

Statistical analyses

Summary statistics were presented by number (percentage), mean (SD) as appropriate. In-order to test the differences in continuous and categorical variables by group, we have used Student’s t-test and chi-square test or Fishers exact test respectively (Table 1). Bivariate comparison of clinical management characteristics, headache referral characteristics, importance of headache treatment outcomes and headache management characteristics were made between chiropractors who indicated the use ICHD headache classification criteria for the diagnosis of primary headaches (i.e. yes/no) using chi-square/Fishers exact test as appropriate (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5).

Multiple logistic regression modelling was then performed to identify independent predictors associated with those chiropractors who use ICHD primary headache criteria (presented in Table 6). Questionnaire response items are dichotomized into “Strongly disagree/Disagree/Neutral” versus “Agree/Strongly agree” with bivariate associations of p < 0.2 included in the regression model. The independent survey variables were dichotomized after consideration of previous research [41, 42] and the distribution of the data. A backward stepwise procedure was chosen to determine the most parsimonious model that predicts those chiropractors who use primary headache diagnostic criteria. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Odds ratios were reported with 95% confidence intervals. All statistical analyses were conducted using the statistical software Stata 13.1.

Results

A total of 1050 chiropractors were invited to participate of which 381 (36.2%) completed the questionnaire. As shown in Table 1, the sub-study sample of participants was compared to the wider ACORN sample and was shown to be similar across gender (p = 0.379), place of practice (p = 0.916) suggesting survey respondents are generally representative (non-significant p values) of the ACORN database participants while our sample was slightly more experienced than the ACORN database members for years in practice (p = 0.003). The majority of questionnaire respondents were male (64%) and the average number of years in practice was 18.1 (SD = 10.9) years. Most participants were educated in Australia including New South Wales (38.6%), Victoria (35.6%), Western Australia (9.7%) and Queensland (0.8%). Place of practice amongst the participants was greatest in New South Wales (35.1%), followed by Victoria (23.2%), Queensland (15.2%), Western Australia (14.7%), South Australia (8.5%), Australian Capital Territory (1.6%), Tasmania (0.9%) and Northern Territory (0.5%). Participant demographic characteristics were consistent with national chiropractic registration records [43].

Factors associated with ICHD use for primary headaches

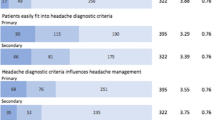

The majority of chiropractors reported utilising ICHD criteria for the diagnosis of primary headaches (84.6%). The clinical management characteristics of chiropractors who use or do not use the ICHD primary headache classification criteria are presented in Table 2. Chiropractors who use ICHD diagnostic criteria for primary headaches were more likely to believe that: ICHD criteria are distinct for the diagnoses of primary headache types; believe ICHD criteria are easy to follow; believe primary headaches easily fit into ICHD diagnostic criteria; believe ICHD criteria influences management of patients with primary headaches; ICHD criteria helps communication with other healthcare professionals; and improves decision-making about patient referral or co-management for those with primary headaches (all p < 0.001). In addition, those chiropractors who use primary headache diagnostic criteria were also more likely to use a Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS); the Headache Disability Inventory (HDI); and patient headache diaries (all p < 0.001).

Table 3 shows the referral characteristics of chiropractors who use or do not use the ICHD primary headache classification criteria. Chiropractors who used the ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria were more likely to receive a headache referral from a general practitioner, medical specialist (including neurologist, rheumatologist, orthopaedic, psychiatrist), psychologist, CAM practitioners (including acupuncturist, herbalist, naturopath, massage therapist, counsellor) (all p < 0.001) and dentist (p = 0.002), compared to chiropractors who do not use the ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria and less likely to receive headache referrals from a physiotherapist (p = 0.684) or osteopath (p = 0.154) although these associations were not statistically significant. Further, chiropractors who use the ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria were also more likely to refer headache patients for further management to general practitioners (p < 0.001), medical specialists (p < 0.001), psychologist (p = 0.004), dentist (p = 0.001), and CAM practitioners (including acupuncturist, herbalist, naturopath, massage therapist, counsellor) (p = 0.001), compared to chiropractors do not use the ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria and were less likely to refer a headache patient to a physiotherapist (p = 0.106) although these associations were not statistically significant. Chiropractors who use ICHD primary headache criteria were more likely to refer patients for reasons of confirming headache diagnosis (p < 0.001), improve coping skills (p < 0.001), investigate headache red-flags (p < 0.001), provide pain relief for acute headache attacks (p = 0.004) and to provide headache prevention (p = 0.004), compared to chiropractors do not use the ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria.

The importance of headache treatment outcomes of chiropractors who use or do not use the ICHD primary headache classification criteria are presented in Table 4. Chiropractors who use ICHD primary headache criteria are more likely to aim their treatment toward improving the recovery from an episode of headaches i.e. postdromal headache period (p = 0.043), to provide pain relief during headache episode (p = 0.049) and improve headache related coping skills (p = 0.001) and less likely to aim treatment toward headache prevention (p = 0.317) or to improve headache patient overall health and well- being (p = 0.411) although these associations were not statistically significant.

Table 5 shows the approaches to primary headache management of chiropractors who use or do not use the ICHD primary headache classification criteria. For patients with migraine, chiropractors who use primary headache diagnostic criteria were also more likely to: provide non-thrust spinal mobilisations (p = 0.001); provide massage, myofascial technique, stretching or trigger-points to neck/shoulder area (p < 0.001); use soft tissue or exercise therapy to temporo-mandibular region (p < 0.001); prescribe exercises for the neck and shoulder region (p < 0.001); provide advice on stress management (p = 0.019) and headache triggers (p = 0.005), compared to chiropractors do not use the ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria. They were less likely to provide manual manipulation (p = 0.751), instrument adjusting (p = 0.407), drop piece adjusting (0.944), electro-physical therapies (p = 0.236) and advice on diet or fitness (p = 0.057) although these associations were not statistically significant. For patients with tension headache, chiropractors who use primary headache diagnostic criteria were more likely to: provide non-thrust spinal mobilisations (p = 0.003); use massage, myofascial technique, stretching or trigger-points to neck/shoulder area (p < 0.001); use soft tissue or exercise therapy to temporomandibular region (p = 0.017); prescribe exercises for the neck/shoulder region (p < 0.001); provide advice on stress management (p = 0.002) and headache triggers (p < 0.001), compared to chiropractors do not use the ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria. They were less likely to provide manual manipulation (p = 0.291), instrument adjusting (p = 0.810), drop piece adjusting (p = 0.662), electro-physical therapies (p = 0.374), and advice on diet and fitness (p = 0.480) although these associations were not statistically significant.

The results of the multiple logistic regression modelling used to identify the important independent factors associated with chiropractors who use ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria compared to those chiropractors who do not use ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria are presented in Table 6. These factors include a belief that: the use of ICHD primary headache criteria will influence their management of patients with primary headaches (OR = 7.86; 95%CI: 3.15, 19.6); improve decision-making about primary headache patient referral/co-management (OR = 2.35; 95%CI: 1.01, 5.47); and not referring headache patients to assist with headache prevention (OR = 0.16; 95%CI: 0.03, 0.80). Chiropractors who use ICHD criteria for the diagnosis of primary headaches are also associated with: believing ICHD criteria are distinct criteria for the diagnoses of primary headache types (OR = 3.64; 95%CI: 1.58, 8.39); ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria influences the use of soft-tissue therapies to neck and shoulder region for tension headache (OR = 4.33; 95%CI: 1.67, 11.19); the use headache diaries as a headache outcome measure (OR = 3.52; 95%CI: 1.41, 8.77) and referral to investigate a headache red-flag (OR = 2.67; 95%CI: 1.02, 6.96).

Discussion

This is the first study to provide detailed information on the patient management features associated with primary headache diagnosis by chiropractors. The majority of chiropractors in our study report utilising ICHD criteria for the diagnosis of primary headaches, a finding which may suggest that chiropractors are sometimes the first point of provider contact for patients seeking help for the management of primary headache disorders. There are a number of factors that can challenge health care providers delivering an accurate primary headache diagnosis. These include the co-occurrence of migraine with both cervicogenic headache [44] and tension-type headache [45], variations in headache characteristics found within headache types [46] and the high prevalence of co-occurring neck pain associated with common recurrent headaches [47, 48]. With misdiagnosis resulting in suboptimal headache patient management [49, 50], poor standards of headache diagnosis have raised concerns about the current level of headache education within primary health care curriculums [11, 49, 51]. Our study found almost half of those chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis implement the use of patient headache diaries. The mixed use of headache diaries has been reported in other primary care settings [52]. While this practice is likely to improve diagnostic accuracy [38, 53], further research would be valuable in assessing the reliability of primary headache diagnosis as undertaken by chiropractors, information that can similarly inform chiropractic educational curriculums. Despite the high percentage of chiropractors self-reporting the utilisation of ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria, uncertainty remains regarding how effectively chiropractors identify headache criteria in order to provide an accurate headache diagnosis.

Our study found several factors that were associated with chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis. These chiropractors include a belief that the use of ICHD primary headache criteria influences their patient management. Previous studies have reported the use of manual therapies, exercise therapies and advice on headache triggers as common to chiropractic headache management [30, 54]. While advice on headache triggers is well recognised as an important aspect of primary headache management [55, 56], the effectiveness of manual and exercise therapies for the prevention of primary headaches requires further evaluation. To date, research evidence supports the role of manual and exercise therapies for the preventative treatment of tension headache [57, 58], while research supporting the role of these therapies for the prevention of migraine remains low quality and inconclusive [59, 60]. In contrast, around 10% of chiropractors who use primary headache diagnosis were not associated with ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria influencing headache management. While this finding requires further investigation, it may be that providing a diagnosis of the patient’s headache type relates more to other motivations for a small number of practitioners. This could include to inform the headache patient or satisfy potential oversight from regulatory authorities. As such, more research is needed to examine how aspects of primary headache patient management are potentially improved through the use of primary headache diagnosis within chiropractic clinical settings.

Our analysis found several factors associated with chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis that were related to specific aspects of practitioner decision-making regarding headache patient management. For example, our study found chiropractors engaged in the use of ICHD primary headache diagnostic criteria are more likely to believe doing so improves decision-making related to headache patient referral/co-management. The health care needs of primary headache sufferers can sometimes be multifactorial and multidisciplinary in nature, particularly for those who present with more complex and chronic headache conditions where a greater use of pharmaceutical, behavioural and physical approaches to patient care may be needed [61, 62]. Previous research has suggested that those with headaches seeking help from manual therapy providers are more likely have a higher rate of headache chronicity and disability than non-users [40]. As such, the belief that primary headache diagnosis improves decision-making about headache patient referral/co-management associated with chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis may reflect practitioner awareness regarding the multidisciplinary health care needs of many primary headache patients within chiropractic patient populations [14, 63].

An unexpected finding from our results was that chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis are less likely to undertake patient referral to assist with headache prevention. A recent Australian study showed chiropractors refer headache patients to both complementary health care providers (including acupuncturist, herbalist, naturopath, massage therapist, counsellor) and general practitioners [30]. For tension headache, preventative treatment guidelines advise non-drug management first be considered [64] and provide recommendations for behavioural treatments such as electromyography (EMG) biofeedback (level A), cognitive-behavioral therapy and relaxation training (level C), massage therapy (level C) and acupuncture (level C). In contrast, preventative treatment guidelines for migraine provide stronger recommendations for drug treatments (Level A) with additional recommendations also provided for several herbs and supplements such as butterbur (Level A), feverfew and magnesium (Level B) and coenzyme Q10 (level C) [65, 66]. Beyond headache diagnosis, provider referral to assist headache prevention requires careful consideration regarding a range of patient factors and circumstances including headache severity, headache comorbidities, patient treatment preferences and response to current care [15, 67, 68]. While more research is needed to understand this finding, one possible explanation is that engagement with headache diagnosis leads to more practitioner certainty about their own capacity to provide sufficient preventative management for those with primary headaches. With increasing examination of the quality and integration of health services and providers engaged in preventative headache management [20, 69], more research examining the factors that influence headache patient co-management between chiropractors and other headache providers is warranted.

Our findings identified chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis are more likely to refer headache patients to investigate a headache red-flag. This finding is not unexpected, since the use of headache diagnostic criteria is more likely to result in the identification of headache features associated with headache red-flag findings. The most important diagnostic consideration for frontline clinicians engaged in headache management is to rule out headaches caused by serious and potentially life-threatening underlying pathology. While rare, the underlying causes associated with headache red-flag symptoms can include stroke, sub-arachnoid haemorrhage, tumour, meningitis and artery dissection (carotid or vertebral) [70]. Since headache features in those with an underlying brain tumour can be similar to those of tension headache and migraine [71], and since neck stiffness and headache in those with underlying meningitis and arterial dissection [72, 73], can be similar to those with cervicogenic headache, chiropractors need to be mindful of the possibility of serious underling pathology when examining those who present with headache.

Our study found that chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis are more likely to use soft tissue therapies such as massage, myofascial technique, stretching or trigger-points to neck/shoulder area for their patients with tension headache. This finding is interesting given a recent systematic review which found manual therapies, including soft tissue therapies, may be more effective than pharmacological care for reducing the short-term frequency, intensity and duration of tension headache [58]. Tenderness of myofascial trigger points of the neck and shoulder muscles are increased in patients with tension-type headache [74, 75]. These active trigger-points appear to cause nociceptive input that contributes to peripheral and central sensitization in patients with chronic tension headache [76]. While further research is needed, these findings appear to support soft tissue treatment approaches that are specifically aimed at addressing these muscular factors.

Limitations

Regression analysis of chiropractors engaged in primary headache diagnosis provides an excellent opportunity to better understand the primary headache management associated with this common headache provider. The self-reported nature of the data collected is a limitation of our study – the data may be subject to recall bias and the use of Likert categories are subject to practitioner interpretation. The headache management characteristics of chiropractors reported in this study may also be influenced by non-respondents to the survey when estimating chiropractors who use of ICHD primary headache criteria and the associations related to their headache management characteristics. Nonetheless, analysis of this cross-sectional survey provides valuable insights into primary headache health management associated with these popular providers and helps to identify key questions for further enquiry into chiropractic headache management.

Conclusion

Our research found that most chiropractors managing primary headaches are engaged in primary headache diagnosis and that this practice is likely to influence their clinical-decision making toward key aspects of primary headache patient management and co-management. These findings highlight the need for closer examination of the clinical decision-making that underlies chiropractic primary headache management and the role of these providers toward reducing the burden of this significant public health issue. Gathering this information will help to improve our understanding of the role of chiropractors within multimodal, multidisciplinary headache patient management.

Abbreviations

- ACORN:

-

Australian Chiropractic Research Network

- CAM:

-

Complementary and alternative medicine

- HDI:

-

Headache Disability Inventory

- ICHD:

-

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- MIDAS:

-

Migraine disability assessment questionnaire

- PBRN:

-

Practice-based research network

References

Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton RB, Scher AI, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193–210.

Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, Freitag F, Reed M, Stewart WF. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Lancet Neurol. 2007;68(5):343–9.

Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):354–61.

Bendtsen L, Jensen R. Tension-type headache: the most common, but also the most neglected, headache disorder. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19(3):305–9.

Malone CD, Bhowmick A, Wachholtz AB. Migraine: treatments, comorbidities, and quality of life, in the USA. J Pain Res. 2015;8:537–47.

Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ, Steiner TJ, Barré J, Katsarava Z, et al. The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol. 2012;19(5):703–11.

Latinovic R, Gulliford M, Ridsdale L. Headache and migraine in primary care: consultation, prescription, and referral rates in a large population. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(3):385–7.

Abu Bakar N, Tanprawate S, Lambru G, Torkamani M, Jahanshahi M, Matharu M. Quality of life in primary headache disorders: a review. Cephalalgia. 2015;36(1):67–91.

Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, Bertozzi-Villa A, Biryukov S, Bolliger I, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800.

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T. GBD 2015: migraine is the third cause of disability in under 50s. J Headache Pain. 2016;7(1):104.

Kernick D, Stapley S, Hamilton W. GPs' classification of headache: is primary headache underdiagnosed? Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(547):102–4.

Diamond S, Bigal ME, Silberstein S, Loder E, Reed M, Lipton RB. Patterns of diagnosis and acute and preventive treatment for migraine in the United States: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache. 2007;47(3):355–63.

Silberstein S, Diamond S, Loder E, Reed M, Lipton R. Prevalence of migraine sufferers who are candidates for preventive therapy: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2005;45(6):770–1.

Barton PM, Schultz GR, Jarrell JF, Becker WJ. A flexible format interdisciplinary treatment and rehabilitation program for chronic daily headache: patient clinical features, resource utilization and outcomes. Headache. 2014;54(8):1320–36.

Nicol AL, Hammond N, Doran SV. Interdisciplinary management of headache disorders. Tech Reg Anesth Pain Manag. 2013;17(4):174–87.

European Headache Federation. EHF Missions. Published Available at http://ehf-org.org/ehf-mission/. Last Accessed 18 July 2017.

Lifting the burden: the global campaign against headache. Vision, aims, Mission. Published Available at https://www.l-t-b.org/go/the_global_campaign/vision_aims_mission. Last Accessed 10 May 2019.

National Headache Foundation. About NHF. Published Available at http://www.headaches.org. Last Accessed 18 July 2017.

Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, Holland S, Reed ML. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2013;53(8):1300–11.

Peters M, Perera S, Loder E, Jenkinson C, Gil Gouveia R, Jensen R, et al. Quality in the provision of headache care. 1: systematic review of the literature and commentary. J Headache Pain. 2012;13(6):437–47.

Stark RJ, Valenti L, Miller GC. Management of migraine in Australian general practice. Med J Aust. 2007;187(3):142.

Nicholson RA. Chronic headache: the role of the psychologist. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(1):47–54.

Grant T, Niere K. Techniques used by manipulative physiotherapists in the management of headaches. Aust J Physiother. 2000;46(3):215–22.

Kristoffersen ES, Grande RB, Aaseth K, Lundqvist C, Russell MB. Management of primary chronic headache in the general population: the Akershus study of chronic headache. J Headache Pain. 2012;13(2):113–20.

Zhang Y, Dennis JA, Leach MJ, Bishop FL, Cramer H, Chung VC, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US adults with headache or migraine: results from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. Headache. 2017;57(8):1228–42.

Wells RE, Phillips RS, Schachter SC, McCarthy EP. Complementary and alternative medicine use among US adults with common neurological conditions. J Neurol. 2010;257(11):1822–31.

Sanderson JC, Devine EB, Lipton RB, Bloudek LM, Varon SF, Blumenfeld AM, et al. Headache-related health resource utilisation in chronic and episodic migraine across six countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(12):1309–17.

Vuković V, Plavec D, Lovrencić Huzjan A, Budisić M, Demarin V. Treatment of migraine and tension-type headache in Croatia. J Headache Pain. 2010;11(3):227–34.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia.38 (3rd edition)(1):1–211.

Moore C, Leaver A, Sibbritt D, Adams J. The management of common recurrent headaches by chiropractors: a descriptive analysis of a nationally representative survey. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):171.

Adams J, Steel A, Moore C, Amorin-Woods L, Sibbritt D. Establishing the ACORN National Practitioner Database: strategies to recruit practitioners to a National Practice-Based Research Network. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2016;39(8):594–602.

Adams J, Peng W, Steel A, Lauche R, Moore C, Amorin-Woods L, et al. A cross-sectional examination of the profile of chiropractors recruited to the Australian chiropractic research network (ACORN): a sustainable resource for future chiropractic research. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):1–8.

Vuillaume De Diego E, Lanteri-Minet M. Recognition and management of migraine in primary care: influence of functional impact measured by the headache impact test (HIT). Cephalalgia. 2005;25(3):184–90.

World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. WHO lifting the burden. Published 2011. Available at http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders.pdf?ua=1. Last Accessed 8 August 2015. 2011.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808.

Jacobson GP, Ramadan NM, Aggarwal SK, Newman CW. The Henry ford hospital headache disability inventory (HDI). Neurology. 1994;44(5):837.

Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner K. Migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) score: relation to headache frequency, pain intensity, and headache symptoms. Headache. 2003;43(3):258–65.

Phillip D, Lyngberg A, Jensen R. Assessment of headache diagnosis. A comparative population study of a clinical interview with a diagnostic headache diary. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(1):1–8.

Adams J, Barbery G, Lui C-W. Complementary and alternative medicine use for headache and migraine: a critical review of the literature. Headache. 2013;53(3):459–73.

Moore CS, Sibbritt DW, Adams J. A critical review of manual therapy use for headache disorders: prevalence, profiles, motivations, communication and self-reported effectiveness. BMC Neurol. 2017;17(1):1–11.

Lee MK, Amorin-Woods L, Cascioli V, Adams J. The use of nutritional guidance within chiropractic patient management: a survey of 333 chiropractors from the ACORN practice-based research network. Chiropr Man Ther. 2018;26(1):7.

Engel RM, Beirman R, Grace S. An indication of current views of Australian general practitioners towards chiropractic and osteopathy: a cross-sectional study. Chiropr Man Ther. 2016;24(1):37.

Chiropractic Board of Australia. Chiropractic registrant data. Published Available at https://www.chiropracticboard.gov.au/about-the-board/statistics.aspx. Last Accessed 29 January 2017.

Knackstedt H, Bansevicius D, Aaseth K, Grande RB, Lundqvist C, Russell MB. Cervicogenic headache in the general population: the Akershus study of chronic headache. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(12):1468–76.

Lyngberg AC, Rasmussen BK, Jørgensen T, Jensen R. Has the prevalence of migraine and tension-type headache changed over a 12-year period? A Danish population survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20(3):243–9.

Lieba-Samal D, Wöber C, Weber M, Schmidt K, Wöber-Bingöl Ç, Group P-S. Characteristics, impact and treatment of 6000 headache attacks: the PAMINA study. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(2):205–12.

Ashina S, Bendtsen L, Lyngberg AC, Lipton RB, Hajiyeva N, Jensen R. Prevalence of neck pain in migraine and tension-type headache: a population study. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(3):211–9.

Bogduk N, Govind J. Cervicogenic headache: an assessment of the evidence on clinical diagnosis, invasive tests, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(10):959–68.

Kingston WS, Halker R. Determinants of suboptimal migraine diagnosis and treatment in the primary care setting. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2017;24(7):319–24.

Lipton RB, Bigal M, Rush S, et al. Migraine practice patterns among neurologists. Neurology. 2004;62(11):1926–31.

Sheftell FD, Cady RK, Borchert LD, Spalding W, Hart CC. Optimizing the diagnosis and treatment of migraine. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17(8):309–17.

Minen MT, Loder E, Tishler L, Silbersweig D. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: a knowledge and needs assessment among primary care providers. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(4):358–70.

Jensen R, Tassorelli C, Rossi P, Allena M, Osipova V, Steiner T, et al. A basic diagnostic headache diary (BDHD) is well accepted and useful in the diagnosis of headache. A multicentre European and Latin American study. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(15):1549–60.

Clijsters M, Fronzoni F, Jenkins H. Chiropractic treatment approaches for spinal musculoskeletal conditions: a cross-sectional survey. Chiropr Man Ther. 2014;22(1):33.

Nicholson RA, Buse DC, Andrasik F. RB L. nonpharmacologic treatments for migraine and tension-type headache: how to choose and when to use. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011;13:28–40.

Haque B, Rahman KM, Hoque A, Hasan AH, Chowdhury RN, Khan SU, et al. Precipitating and relieving factors of migraine versus tension type headache. BMC Neurol. 2012;12(1):82.

Van Ettekoven H, Lucas C. Efficacy of physiotherapy including a craniocervical training programme for tension-type headache; a randomized clinical trial. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(8):983–91.

Mesa-Jiménez JA, Lozano-López C, Angulo-Díaz-Parreño S, Rodríguez-Fernández ÁL, De-la-Hoz-Aizpurua JL, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Multimodal manual therapy vs. pharmacological care for management of tension type headache: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(14):1323–32.

Posadzki P, Ernst E. Spinal manipulations for the treatment of migraine: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Cephalalgia. 2011;31(8):964–70.

Chaibi A, Tuchin PJ, Russell MB. Manual therapies for migraine: a systematic review. J Headache Pain. 2011;12(2):127–33.

Gunreben-Stempfle B, Grießinger N, Lang E, Muehlhans B, Sittl R, Ulrich K. Effectiveness of an intensive multidisciplinary headache treatment program. Headache. 2009;49(7):990–1000.

Becker WJ. The diagnosis and Management of Chronic Migraine in primary care. Headache. 2017;57(8):1471–81.

Gaul C, Visscher CM, Bhola R, Sorbi MJ, Galli F, Rasmussen AV, et al. Team players against headache: multidisciplinary treatment of primary headaches and medication overuse headache. J Headache Pain. 2011;12(5):511–9.

Bendtsen L, Evers S, Linde M, Mitsikostas DD, Sandrini G, Schoenen J. EFNS guideline on the treatment of tension-type headache – report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(11):1318–25.

Holland S, Silberstein SD, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E. Evidence-based guideline update: NSAIDs and other complementary treatments for episodic migraine prevention in adults. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1346–53.

Loder E, Burch R, Rizzoli P. The 2012 AHS/AAN guidelines for prevention of episodic migraine: a summary and comparison with other recent clinical practice guidelines. Headache. 2012;52:930–45.

Zheng Y, Tepper SJ, Covington EC, Mathews M, Scheman J. Retrospective outcome analyses for headaches in a pain rehabilitation interdisciplinary program. Headache. 2014;54(3):520–7.

Zebenholzer K, Lechner A, Broessner G, Lampl C, Luthringshausen G, Wuschitz A, et al. Impact of depression and anxiety on burden and management of episodic and chronic headaches–a cross-sectional multicentre study in eight Austrian headache centres. J Headache Pain. 2016;17(1):15.

Gaul C, Liesering-Latta E, Schäfer B, Fritsche G, Holle D. Integrated multidisciplinary care of headache disorders: a narrative review. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(12):1181–91.

Ravishankar K. WHICH headache to investigate, WHEN, and HOW? Headache. 2016;56(10):1685–97.

Sarah N, TL P. Headaches in brain tumor patients: primary or secondary? Headache. 2014;54(4):776–85.

Van de Beek D, De Gans J, Spanjaard L, Weisfelt M, Reitsma JB, Vermeulen M. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(18):1849–59.

Debette S, Leys D. Cervical-artery dissections: predisposing factors, diagnosis, and outcome. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):668–78.

Fernández-de-las-Penas C, Ge H-Y, Alonso-Blanco C, González-Iglesias J, Arendt-Nielsen L. Referred pain areas of active myofascial trigger points in head, neck, and shoulder muscles, in chronic tension type headache. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2010;14(4):391–6.

Fernández-De-Las-Peñas C, Arendt-Nielsen L. Improving understanding of trigger points and widespread pressure pain sensitivity in tension-type headache patients: clinical implications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(9):933–9.

Bendtsen L, Fernández-de-la-Peñas C. The role of muscles in tension-type headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(6):451–8.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper is the sole responsibility of the authors and reflects the independent ideas and scholarship of the authors alone. The authors would like to thank the chiropractors who participated in the study and the Australian Chiropractors’ Association for their financial support for the ACORN PBRN.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public,

commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The data are not publicly available because the participants were not informed about this when they accepted participation but are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM, JA, AL, and DS designed the study. CM and DS carried out the data collection, analysis and interpretation. CM wrote the drafts with revisions made by JA, DS and AL. All authors contributed to the intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Technology Sydney (Approval number: ETH16–0639).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests related to the contents of this manuscript and that they have received no direct or indirect payment in preparation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Moore, C., Leaver, A., Sibbritt, D. et al. Prevalence and factors associated with the use of primary headache diagnostic criteria by chiropractors. Chiropr Man Therap 27, 33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-019-0254-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-019-0254-y