Abstract

Background

Evidence from published literature in pharmacy practice research demonstrate that the use of competency frameworks alongside standards of practice facilitate improvement in professional performance and aid expertise development. The aim of this study was to evaluate pharmacists’ perception of relevance to practice of the competencies and behaviours contained in the FIP Global Competency Framework (GbCF v1). The overall objective of the study was to assess the validity of the GbCF v1 framework in selected countries in Africa.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of pharmacists practicing in 14 countries in Africa was conducted between November 2012 and December 2014. A combination of purposive and snowball sampling method was used. Data was analysed using SPSS v22.

Results

A total of 469 pharmacists completed the survey questionnaire. The majority (91%) of the respondents were from four countries: Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa. The study results showed broad agreement on relevance to practice for 90% of the behaviours contained in the GbCF v1 framework. Observed disagreement was associated with area of pharmacy practice and the corresponding patient facing involvement (p ≤ 0.05). In general, the competencies within the ‘pharmaceutical care’ and ‘pharmaceutical public health’ clusters received higher weighting on relevance compared to the research-related competencies which had the lowest. Specific inter-country variability on weighting of relevance was observed in five behaviours in the framework although, this was due to disparity in ‘degree of relevance’ that was related to sample composition in the respective countries.

Conclusion

The competencies contained in the GbCF v1 are relevant to pharmacy practice in the study population; however, there are some emergent differences between the African countries surveyed. Overall, the findings provide preliminary evidence that was previously lacking on the relevance of the GbCF v1 competencies to pharmacy practice in the countries surveyed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Competent pharmacists improve therapeutic outcomes, minimise the risk associated with medicines use and assure patient safety through the provision of medicine expertise [1,2,3,4,5]. The central role pharmacists play within the health system underpins the demand for a competent and highly skilled workforce that is equipped with the requisite knowledge and skills relevant to population health needs [6,7,8]. This is of particular importance in resource-limited settings such as in sub-Saharan Africa where severe workforce shortages hamper access to health services including medicines expertise [9, 10].

The International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) is the global leadership body representing 3 million pharmacists and pharmaceutical scientists worldwide [11]. FIPEd, which is the pharmacy education and workforce development arm of the FIP, advocates the need to define and articulate the competencies that pharmacists require to consistently perform safely, effectively, and efficiently [12]. The overall objective is to provide an infrastructure for global guidance on the practice-based expectations of the pharmacy workforce [13].

Published research demonstrate that when competency frameworks are used alongside standards of practice: it facilitates improvement of pharmacists’ performance [14,15,16,17], promotes the attainment and maintenance of fitness to practice [17, 18], aids identification of knowledge gaps and learning needs [19], and fosters continuing professional development [20]. The findings of longitudinal studies show that using competency frameworks to identify knowledge gaps and tailor learning activities significantly improve pharmacists’ performance (p ≤ 0.05) at 6 months [14, 15, 17], 9 months [16], and 12 months [18, 20]. Similar findings from comparative studies conducted in United Kingdom [14, 20] indicate that competency frameworks facilitate a more sustained improvement in pharmacists’ performance (p < 0.001) in the intervention group at 12 months when compared to a control group that had no access to a framework. These findings have also been corroborated by other studies in Australia [15], Croatia [18], Serbia [17], and Singapore [16].

In 2012, FIPEd developed the FIP Global Competency Framework (GbCF v1) using evidence-based methodologies [21]. This framework was specifically designed to serve as a source document containing the core competencies expected of foundation level pharmacy practitioners (this means, pharmacists with less than 5 years practice experience) [13]. Since its development, the GbCF v1 has been successfully used to design pre-service education and training curriculum in a number of countries [22, 23]. It has also been used to develop country-specific frameworks for in-service practitioners in Ireland [24], the Pacific Island countries [25], Croatia, Singapore and Serbia [21]. A previous survey that validated the GbCF v1 using evidence from 64 countries [26] showed that 70% of respondents ranked all the behaviours in the questionnaire as relevant to practice. However, respondents from countries in Africa comprised only 12.3% of the total sample in the survey [26]. The aim of this present study was therefore to evaluate pharmacists’ perception of the relevance to practice of the competencies and behaviours contained in the GbCF v1, focusing on selected African countries.

Methods

Data collection and sampling

A cross-sectional survey of pharmacists practicing in selected countries in Africa was conducted between November 2012 and December 2014. A combination of purposive and snow-ball sampling method was used. Due to a lack of access to the pharmacy membership list of the respective countries in Africa, the URL link to the online survey was circulated centrally via email to the 35 FIP member organisations in Africa for onward distribution to their respective individual members. The FIP member organisations contacted were the leadership bodies representing practicing pharmacists in 24 countries in Africa (list provided in the Appendix). These organisations were selected based on availability of contact persons, expression of interest to participate when contacted and willingness to gather data. The survey invite was also disseminated through the FIP United Nations Education Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) University Twining Network (FIP UNESCO UNITWIN) in Africa. The survey URL link was further customised and distributed via social media and short message service platforms including Facebook®, Twitter®, WhatsApp® and Blackberry Messenger®. Respondents were encouraged to assist by forwarding the survey URL link to their colleagues and contacts. Email reminders were thereafter forwarded monthly through the aforementioned media until the end of the study. Due to the non-availability of reliable estimates on the number of pharmacists per country organisation represented in FIP, a sampling frame was not feasible and survey respondents were therefore recruited consecutively until the end of the study period.

Survey questionnaire

An anonymous online questionnaire developed and validated in a previous study [26] was used. The questionnaire was fully reproduced from the GbCF v1 and comprised of 105 questions. Five questions related to demographic information while the remaining questions referred to the 100 GbCF v1 behavioural statements (labelled B1 through B100, and hereafter referred to as ‘behaviours’). These behaviours are grouped under the 20 competency domains and four broad competency clusters in the framework (Table 1).

Data analysis

Survey data was collected electronically, without transformation and analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. To ensure data quality, a random 10% of the total survey sample was reviewed for coding errors with missing values replaced with code 999. Respondents’ perception of relevance to practice of each of the behaviours was evaluated using a 4-point Likert scale. Respondents were required to rank each of the 100 GbCF v1 behaviours as ‘not relevant’, of ‘low relevance’, ‘relevant’ or ‘highly relevant’ to their practice. For the purpose of analysis and to ensure the results produced could be meaningfully interpreted, the response categories in the Likert scale were further aggregated. The ‘highly relevant’ and ‘relevant’ ratings were condensed into one category: ‘relevant’, while the ‘low relevance’ and ‘not relevant’ ratings remained distinct categories. Agreement was evaluated by comparing the proportion (frequency and percentage) of the total ratings in the three categories. Consensus on relevance to practice was attained when not more than 10% of the respondents ranked a given behaviour as ‘not relevant’. This threshold was defined empirically based on previous research involving pharmacists from 64 countries [26].

Pearson’s chi-square (χ2) test was used to assess homogeneity in the survey sample. The test of homogeneity was undertaken to ascertain whether the sample could be treated as a group irrespective of the number of replies received per country. The χ2 test was also used to evaluate the relationship between weighting of relevance and area of practice for behaviours that showed a lack of consensus. In order to assess inter-country variability in responses, multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) via Pillia’s trace test (V) was used to evaluate weighting of relevance per country per competency with confirmatory post hoc analysis conducted using Bonferroni correction.

Ethical consideration

Formal ethical approval from the research ethics committee was not required for this study as it did not involve the use of identifiable patient information or data, rather the study recruited pharmacists and sought their views by virtue of their professional roles. However, consent to participate was sought from the respondents prior to completing the survey questionnaire. Participation was voluntary, and confidentiality was maintained at all times with responses remaining anonymous. All data collected in the research were stored in an encrypted database with hard copies kept in locked filling cabinets at the Department of Practice and Policy, UCL School of Pharmacy, United Kingdom. Access to study data was restricted to the three researchers directly involved with the study.

Results

Demography

Four hundred and sixty-nine pharmacists from 14 countries in Africa responded to the survey. Over half of the survey respondents were female (54%). The mean length of practice was 7.7 years (SD ± 8.1 years; min–max 1–43 years). Respondents with less than 5 years practice experience made up 47% of the sample while pre-registration candidates/pharmacy students in their last year (internship) comprised 5.5%. The majority of the respondents were in hospital practice (56.7%). Table 2 shows the summary of the distribution of survey replies per country and area of pharmacy practice.

Sample homogeneity

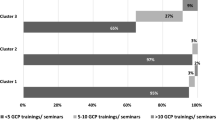

Four countries—Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Ghana—each had more than 50 replies and made up 91% of the sample. Ten countries—Ethiopia, Egypt, Lesotho, Uganda, Tunisia, Namibia, Sudan, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe—had fewer than 20 survey replies each. The observed disparity in number of replies indicated two cluster groups: a ‘high response group’ made up of countries with more than 50 replies each, and a ‘low response group’ made up of countries with fewer than 20 replies each. The number of replies also varied for the four competency clusters in the framework. Table 3 shows a summary of the distribution of replies for each competency cluster per country group.

The test for homogeneity in the survey sample showed that distribution of the ratings in the response categories (that is, in the ‘relevant’, ‘low relevance’ and ‘not relevant’ categories) was strongly associated with the country group for 11 behaviours [(p < 0.01); Table 4]. These 11 behaviours were distributed across the four competency clusters in no observable pattern. The outcome of the χ2 test implied homogeneity in responses between the country groups for 89% of the GbCF v1 behaviours. The low counts (frequency of less than 5) observed in the table cells within the group with low number of replies (N < 20 per country; Table 4) suggested an absence of data in this group rather than disparity in responses between countries. Given the χ2 test known property of being imprecise in ‘small’ samples [27,28,29], it is likely that the test overestimated the relationship between the responses and the country group. Based on this, sample homogeneity was assumed and the survey replies were subsequently analysed as a group. Figure 1 shows the percentage of ratings in the ‘relevant’ category for the low response, high response, and combined group of countries, respectively. The total ratings in the combined country groups indicate that at least 70% of survey respondents ranked all the behaviours in the framework as ‘relevant’. This was not inclusive of the ‘not relevant’ and ‘low relevant’ ratings.

Overall perception of relevance

Consensus on relevance to practice (N ‘not relevant’ < 10%) was obtained for 90 behaviours in the questionnaire. This included all the behaviours in the ‘pharmaceutical public health’ cluster, 84% in the ‘pharmaceutical care’, 90% in ‘organisation and management’ and 92% in the ‘professional and personal’ cluster, respectively (please see Tables 5, 6, 7 and 8). The 10 behaviours with more than 10% of the total ratings in the ‘not relevant’ category, suggested disagreement on relevance to practice (Table 9). This observed disagreement was associated with area of pharmacy practice for six of the ‘disagreed’ behaviours (Table 9; P < 0.05).

The disagreement was also associated with ‘patient-facing role’ in practice area [(P < 0.05); Table 10]. A higher percentage of the respondents in the ‘non-patient’ facing areas of practice (this means area of pharmacy practice with little or no daily patient interactions such as industrial and academic pharmacy) ranked the behaviours that showed disagreement in the ‘pharmaceutical care’ (B6, B13, B14, B20) and ‘organisation and management’ cluster (B32, B34, B58) as ‘not relevant’ compared to respondents in the ‘patient-facing’ practice areas (such as hospital and community pharmacy) (Table 10). The converse was true for the research-related (B87 and B95) and quality control (B90) behaviours (Table 10).

Perception of relevance per competency per country

Inter-country variability in responses was assessed for each of the 20 competencies in the questionnaire. For ease of interpretation, the analysis included 426 replies from four countries: Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Ghana with the 10 countries that had fewer than 20 survey replies each excluded. The result showed similarity in weighting of relevance for the competencies in the ‘pharmaceutical public health’ (Pillia’s trace V = 0.025, F = 1.809, df = 6, p = 0.094), and ‘professional and personal’ (Pillia’s trace V = 0.084, F = 1.270, df = 18, p = 0.2) clusters, respectively. Specific inter-country variability was observed in the ‘pharmaceutical care’ (Pillia’s trace V = 0.083, F = 1.624, df = 18, p = 0.045), and ‘organisation and management’ (Pillia’s trace V = 0.136, F = 2.279, df = 18, p = 0.002) clusters.

Confirmatory post hoc analysis using Bonferroni correction showed the inter-country variability in responses observed within the ‘pharmaceutical care’ cluster was in three behaviours: B6 [‘assessment of medicine (AM)]’ and B25 and B27 [‘patient consultation and diagnosis (PCD)’] competencies. This was between South Africa and Ghana [in B6: N ‘relevant’ = 47% vs 71%)], Nigeria and Kenya [in B25: N ‘relevant’ = 98 vs 89%], and Nigeria and Ghana [in B27: N ‘relevant’ = 98 vs 85%)]. In spite of the observed disparity in weighting of relevance, only South Africa showed a lack of consensus on relevance (N ‘not relevant’ = 15%) for this cluster and this was in the B6 behaviour.

The disparity in the organisation and management cluster was in B32 [‘budget and reimbursement (BR)’], B45 [‘procurement (P)’] and B55 [‘supply chain and management (SCM)’] competencies. More of the respondents from Ghana rated the B32, B45 and B55 behaviours ‘relevant’ compared to Nigeria (75%, 92%, 94% vs 70%, 70%, 79%, respectively). A lack of consensus on relevance was observed in the South Africa and Nigeria group for the B32 (N ‘not relevant’ = 11%) and B49 (N ‘not relevant’ = 11%) behaviours, respectively. Since only Nigeria and South Africa showed a lack of consensus (N ‘not relevant’ > 10%) on relevance to practice for three behaviours in the framework, it suggests that the inter-country variability in weighting of relevance observed in this study indicated differences in perception of ‘degree of relevance’ between countries. This variability is likely due to the disparity in sample composition in the respective countries given that Kenya had a higher percentage of the respondents in hospital practice (86%) while Nigeria and South Africa on the other hand had less than 50% respectively. Also, more than a third of the respondents from South Africa were in academic pharmacy compared to Nigeria, Kenya and Ghana with less than 7% each.

Discussion

The disagreement observed in 10 behaviours in the GbCF v1 framework was mainly related to respondents’ area of pharmacy practice and the corresponding patient-facing involvement, a finding that is consistent with evidence from previous research [26]. The disagreement in the four behaviours under the ‘pharmaceutical care’ cluster observed in academic and industrial pharmacy is also in line with the scope of practice of pharmacists in these areas given that they are not routinely involved in activities related to medicine assessment and medicines use. This also explains the disagreement observed in the three behaviours under the ‘organisation and management’ cluster.

On the other hand, the disagreement in the research-related behaviours (B87 and B95) under the ‘professional and personal’ cluster was not fully explained by area of pharmacy practice or ‘patient-facing’ involvement. A high percentage (N > 10%) of the respondents in academic and community pharmacy rated these same behaviours ‘not relevant’, thereby adding to the increasing body of evidence from other studies that suggest that pharmacists are not routinely involved in research [30,31,32,33] and perceive their research-related roles to be of low importance [34,35,36,37]. It also corroborates the findings of published studies from Australia [38], United Kingdom [39] and Thailand [40] that show that pharmacists generally perceive research-related behaviours and competencies included in developmental frameworks to be relatively low in relevance and rank them accordingly. Time constraints due to workload and a lack of supporting environment for pharmacy research are some of the barriers to participation in research-related activities in the workplace reported in existing literature [38, 41, 42]. Given that the survey respondents in our study included international pharmacists from different areas of pharmacy practice and with varying length of practice experience, this finding highlights the need to scale up efforts to build research capacity in this region.

Of particular interest is the finding that a high percentage (N > 15%) of community pharmacists from the countries represented in this survey ranked two dispensing-related behaviours: B13 (document and act upon dispensing errors) and B14 (implement and maintain a dispensing error report system and a near miss report system) ‘not relevant’ to practice. This suggests community pharmacy respondents from these countries do not routinely carry out these activities although this may have been due to the response rate and/or that the pharmacists were self-selecting. However, available evidence suggests this may also be related to the peculiarities of community pharmacy practice in countries with severe health workforce shortages such as Nigeria [43] and Zambia [44]. Studies show that dispensing activities in community pharmacies in Nigeria are mainly carried out by pharmacy assistants and in some instances, by sales personnel or clerks [43].

Furthermore, the finding may also be related to evidence that suggest that many countries including those in Africa either lack a defined medication error reporting system [45, 46] or where available such systems are primarily independent and/or based within a specific healthcare facility [45, 47]. Given the broad similarities in pharmacy practice reported in countries within the African region [48] and published reports of high incidence of patient harm due to medication errors in some of the countries represented in this survey [49, 50]. This finding underscores the need to review current practice and incorporate robust dispensing and medication error reporting processes in community practice with oversight functions by pharmacists in order to assure patient safety.

Homogeneity in sample responses and the overall survey results indicate minimal disparity between countries in perception of relevance to practice for majority of the behaviours in the GbCF v1. This finding corroborates evidence from previous research [26] and provides evidence that was previously lacking on the relevance of the GbCF v1 competencies in these countries. The finding is in consonance with similar evidence from the field of medicine that demonstrates the relevance of the Canadian CanMEDS Physician Competency Framework to medical practice in the Netherlands [51], Denmark [52, 53] and Australia [54]. It is also in line with evidence from studies that show consensus between countries in Europe on the relevance of a core set of competencies for pharmacy education and practice [42, 55].

Although evidence from global studies have shown that continuous professional development (CPD) is mandatory in many countries in Africa, none of the countries represented in this survey have reported the availability of a validated competency framework for early career pharmacy practice [7, 56]. Studies conducted in Ghana, Ethiopia and Sudan suggest that the lack of a structured post-registration pathway for skills development contribute to the comparatively lower levels of job satisfaction shown by early career pharmacists in these countries [57,58,59]. Our findings therefore provide preliminary evidence on the validity of a core set of competencies that can be further adapted to country context and used to design skill development and learning activities for pre- and in-service early career pharmacy practitioners in these countries. Our findings also suggests the feasibility of adapting the GbCF v1 to develop country-specific frameworks for use in facilitating performance improvement and identifying learning needs particularly in the four countries with comparatively high number of replies in this study.

This study has some limitations. The length of the survey questionnaire (105 questions presented over six pages) may have negatively impacted on the number of replies received. Findings from a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials show that the odds of a response decreases by more than half as the number of pages of a survey questionnaire increases [OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.45] [60]. This was particularly obvious with the consistent decrease in number of replies per additional competency cluster in the survey questionnaire (Additional file 1). Nonetheless, research also demonstrates that the variation in response rates per page of a questionnaire does not affect the quality of the overall responses received [61].

Online surveys are generally associated with low response rates particularly because it restricts the target populations to individuals with internet access [62, 63]. This implies that potential respondents without Internet access were excluded from this survey, a feature that is significant given that our study was conducted in countries that have been shown to have comparatively higher cost and lower Internet accessibility [64, 65]. However, the geographical location of the survey population, limited resources and time available for this research precluded the use of a telephone or postal survey. Participant self-selection and the non-probabilistic sample obtained via the purposive and snowball sampling technique in our study likely limits the generalisability of our findings. Studies show that self-selected participants are likely to be more intrinsically motivated than the general population [66]. This non-random sampling method was undertaken due to challenges with obtaining a sampling frame for the respective countries. For this same reason, it was difficult to estimate an optimal sample size a priori and to calculate a response rate. In spite of these limitations, the methods used in our study are established and pragmatic evidence-based approaches in pharmacy practice research [26, 38,39,40]. Furthermore, given that our study was an exploratory survey, our findings provide useful information on pharmacists’ perception of relevance to practice of the competencies and behaviours contained in the GbCF v1 framework in the countries represented.

Further work is necessary to qualitatively explore expert opinion and obtain insight from other stakeholders including policy-makers and pharmacy leaders on the validity of these competencies in the respective countries. Also, a larger scale validation study is needed to obtain further inputs from practitioners in non-patient-facing roles such as industrial, administrative and academic pharmacy in this region. This will provide an opportunity for further review of the GbCF v1 competencies in relation to these specific areas of practice.

Conclusion

The majority (90%) of the competencies in the framework as relevant to practice for the respondents in this survey, although there are some emergent differences in weighting of relevance between the countries represented. Overall, the findings provide preliminary evidence that was previously lacking on the relevance of the GbCF v1 competencies to pharmacy practice in these countries.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

Assessment of medicine competency

- BR:

-

Budget and reimbursement competency

- D:

-

Dispensing competency

- FIP:

-

The International Pharmaceutical Federation

- FIPEd:

-

The International Pharmaceutical Federation Education Initiative

- GbCF v1:

-

Global Competency Framework version 1

- M:

-

Medicines competency

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- P:

-

Procurement competency

- PCD:

-

Patient consultation and diagnosis competency

- SCM:

-

Supply chain and management competency

- SPSS v22:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22

References

Bond CA, Raehl CL. Clinical pharmacy services, pharmacy staffing, and hospital mortality rates. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2007;27(4):481–93.

Fairbanks RJ, Hildebrand JM, Kolstee KE, Schneider SM, Shah MN. Medical and nursing staff highly value clinical pharmacists in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(10):716–8.

Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcome through advanced pharmacy practice. [Internet]. Office of the Chief Pharmacist, U.S. Public Health Service; 2011 Dec [cited 2012 Oct 24] p. 1–95. (Report to the Surgeon General). Available from: http://www.usphs.gov/corpslinks/pharmacy/sc_comms_sg_report.aspx.

Jacknin G, Nakamura T, Smally AJ, Ratzan RM. Using pharmacists to optimize patient outcomes and costs in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32(6):673–7.

Lada P, Delgado G. Documentation of pharmacists’ interventions in an emergency department and associated cost avoidance. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64(1):63–8.

Austin Z. CPD and revalidation: our future is happening now. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2013;9(2):138–41.

International Pharmaceutical Federation. The 2012 FIP global pharmacy workforce report. The Hague: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2012.

International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Advanced practice and specialisation in pharmacy: global report 2015 [Internet]. The Hague, Netherlands: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2015. Available from: http://www.fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/Adv_and_Spec_Survey/FIPEd_Advanced_2015_web_v2.pdf. Accessed Mar 2018.

Global Health Workforce Alliance. A universal truth: no health without a workforce. Brazil: Global Health Workforce Alliance and World Health Organization; 2013. p. 90. Available from: http://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/GHWA-a_universal_truth_report.pdf?ua=1.

International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Global pharmacy workforce intelligence: trends report. The Hague: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2015. Available from: http://www.fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/Trends/FIPEd_Trends_report_2015_web.pdf.

About FIP—FIP—International Pharmaceutical Federation [Internet]. [cited 2017 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.fip.org/?page=menu_about.

Bates I, Bruno A. Competence in the global pharmacy workforce: a discussion paper. Int Pharm J. 2008;23(2):30–3.

Bruno A, Bates I, Brock T, Anderson C. Towards a global competency framework. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3):1–2.

Antoniou S, Webb DG, McRobbie D, Davies JG, Wright J, Quinn J, et al. A controlled study of the general level framework: results from the South of England competency study. Pharm Educ. 2005;5:201–7.

Coombes I, Avent M, Cardiff L, Bettenay K, Coombes J, Whitfield K, et al. Improvement in pharmacist’s performance facilitated by an adapted competency-based general level framework. J Pharm Pract Res. 2010;40(2):111–8.

Rutter V, Wong C, Coombes I, Cardiff L, Duggan C, Yee M-L, et al. Use of a general level framework to facilitate performance improvement in hospital pharmacists in Singapore. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(6):107.

Svetlana S, Ivana T, Tatjana C, Duskana K, Bates I. Evaluation of competences at the community pharmacy settings. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 2014;48(4):22–30.

Meštrović A, Staničić Ž, Hadžiabdić MO, Mucalo I, Bates I, Duggan C, et al. Individualized education and competency development of Croatian community pharmacists using the general level framework. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76(2):23.

Meštrović A, Staničić Z, Hadžiabdić MO, Mucalo I, Bates I, Duggan C, et al. Evaluation of Croatian community pharmacists’ patient care competencies using the general level framework. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(2). Article 36.

Mills E, Bates I, Farmer D, Davies G, Webb DG. The general level framework: use in primary care and community pharmacy to support professional development. Int J Pharm Pract. 2008;16(5):325–31.

FIP Education Initiatives. A global competency framework for services provided by pharmacy workforce: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2012. p. 21. https://www.fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/GbCF/GbCF_v1_online_A4.pdf.

International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). 2013 FIPEd global education report. The Hague: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2013. 52 p.

International Pharmaceutical Federation. Transforming our workforce [Internet]. International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2016 [cited 2017 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/2016_report/FIPEd_Transform_2016_online_version.pdf.

The Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland. Core competency framework for pharmacists. Dublin: Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland; 2013. Available from: http://www.thepsi.ie/Libraries/Publications/PSI_Core_Competency_Framework_for_Pharmacists.sflb.ashx.

Brown AN, Gilbert BJ, Bruno AF, BPharm GMC. The pharmacy competency framework for Pacific Island countries. J Pharm Pract Res. 2012;42(4):268–72.

Bruno AF. The feasibility, development and validation of a global competency framework for pharmacy education, PhD thesis. School of Pharmacy, University of London. London: School of Pharmacy, University of London; 2011.

Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics review 8: qualitative data—tests of association. Crit Care. 2004;8(1):46–53.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Weisburd D, Britt C. Measures of association for nominal and ordinal variables. In: Statistics in criminal justice. Third. New York: Springer US; 2007. p. 335–380. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-34113-2_13.

Armour C, Brillant M, Krass I. Pharmacists’ views on involvement in pharmacy practice research: strategies for facilitating participation. Pharm Pract. 2007;5(2):59–66.

Awaisu A, Bakdach D, Elajez RH, Zaidan M. Hospital pharmacists’ self-evaluation of their competence and confidence in conducting pharmacy practice research. Saudi Pharm J. 2014;(0). Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1319016414001121. Accessed Mar 2018.

Fagan SC, Touchette D, Smith JA, Sowinski KM, Dolovich L, Olson KL, et al. The state of science and research in clinical pharmacy. Pharmacother J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther. 2006;26(7):1027–40.

Rosenbloom K, Taylor K, Harding G. Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards research. Int J Pharm Pract. 2000;8(2):103–10.

Hébert J, Laliberté M-C, Berbiche D, Martin E, Lalonde L. The willingness of community pharmacists to participate in a practice-based research network. Can Pharm J CPJ. 2013;146(1):47–54.

Kanjanarach T, Numchaitosapol S, Jaisa-ard R. Thai pharmacists’ attitudes and experiences of research. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2012;8(6):e58–9.

Liddell H. Attitudes of community pharmacists regarding involvement in research. Pharm J. 1996;256:905–7.

Saini B, Brillant M, Filipovska J, Gelgor L, Mitchell B, Rose G, et al. Factors influencing Australian community pharmacists’ willingness to participate in research projects: an exploratory study. Int J Pharm Pract. 2006;14(3):179–88.

Carrington C, Weir J, Smith P. The development of a competency framework for pharmacists providing cancer services. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2011;17(3):168–78.

Jones SC, Fleming G, Hay D, Ibrahim M, Pettit M, Wright E, et al. Development and piloting of a competency framework for pharmacy educational and practice supervisors. Pharm Educ. 2012;12(1):14–9.

Maitreemit P, Pongcharoensuk P, Kapol N, Armstrong EP. Pharmacist perceptions of new competency standards. Pharm Pract. 2008;6(3):113–20.

Kennie-Kaulbach N, Farrell B, Ward N, Johnston S, Gubbels A, Eguale T, et al. Pharmacist provision of primary health care: a modified Delphi validation of pharmacists’ competencies. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):1–9.

Atkinson J, Paepe KD, Pozo AS, Rekkas D, Volmer D, Hirvonen J, et al. The PHAR-QA project: quality assurance in European pharmacy education and training. Results of the European network Delphi round 1: PHAR-QA Newsletter. PHARMINE; 2015. p. 1–31.

Adje DU, Oli AN. Community pharmacy in Warri, Nigeria: a survey of practice details. Sch Acad J Pharm SAJP. 2013;2(5):391–7.

Machula MC. Effect of trade liberalisation on community pharmacy in Zambia: a case study of the Copperbelt region [Internet] [MBA Thesis]. [Zambia]: The Copperbelt Uinversity School of Business Postgraduate Studies; 2007. Available from: http://dspace.cbu.ac.zm:8080/jspui/bitstream/123456789/127/1/MACHULA%2c%20C.%20MOSES0001%20-%20Effect%20of%20trade%20liberalisation%20on%20community%20pharmacy.%20A%20case%20study%20of%20The%20Copperbelt%20University.PDF. Accessed Mar 2018.

Terzibanjan A-R, Laaksonen R, Weiss M, Airaksinen M, Wuliji T. Medication error reporting systems—lessons learnt. Executive summary of the findings [Internet]. International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2008 [cited 2017 Oct 12]. Available from: http://www.fip.org/files/fip/Patient%20Safety/Medication%20Error%20Reporting%20-%20Lessons%20Learnt2008.pdf.

Chukwuneke F. Medical incidents in developing countries: a few case studies from Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2015;18(7):20–4.

Walker EE. Strategies to reduce medication errors (II): Pharmaceutical Society of Ghana; 2016. Available from: https://psgh.site-ym.com/page/V5N3_medicationerror/Strategies-to-reduce-medication-errors-II.htm. Accessed Mar 2018.

Kassi M. Pharmacy in Africa [Internet]. The Ohio State University School of Pharmacy; 2016 [cited 2017 Oct 12]. Available from: http://pharmacy.osu.edu/sites/default/files/forms/outreach/intro2pharm/global-practices/Pharmacy-in-Africa_Kassi.pdf.

Wilson RM, Michel P, Olsen S, Gibberd RW, Vincent C, El-Assady R, et al. Patient safety in developing countries: retrospective estimation of scale and nature of harm to patients in hospitals. Br Med J. 2012;13:344.

Llewellyn RL, Gordon PC, Reed AR. Drug administration errors: time for national action. SAMJ South Afr Med J. 2011;101:319–20.

Scheele F, Teunissen P, Luijk SV, Heineman E, Fluit L, Mulder H, et al. Introducing competency-based postgraduate medical education in the Netherlands. Med Teach. 2008;30(3):248–53.

Danish Health and Medicines Authority. The seven roles of physicians [Internet]. Danish Health and Medicines Authority; 2014 [cited 2017 Jan 13]. Available from: https://www.sst.dk/en/news/2013/~/media/39D3E216BCBF4A9096B286EE44F03691.ashx.

Ringsted C, Hansen TL, Davis D, Scherpbier A. Are some of the challenging aspects of the CanMEDS roles valid outside Canada? Med Educ. 2006;40(8):807–15.

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. Fellowship statements and competencies [Internet]. Melbourne, Australia: The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists; 2012 [cited 2017 Jan 13] p. 3. Available from: https://www.ranzcp.org/Files/PreFellowship/2012-Fellowship-Program/Fellowship-Competencies.aspx.

Atkinson J, Rombaut B, Pozo AS, Rekkas D, Veski P, Hirvonen J, et al. Production of a framework of competences for pharmacy practice in the European Union. Pharmacy. 2014;2(2):161–74.

International Pharmaceutical Federation. Continuing professional development and continuing education in pharmacy: a global report [Internet]. The Hague, Netherlands: International Pharmaceutical Federation; 2014 p. 44. Available from: http://www.fip.org/files/fip/PharmacyEducation/CPD_CE_report/FIP_2014_Global_Report_CPD_CE_online_version.pdf. Accessed Mar 2018.

Duwiejua M, Danquah DA, Andrews-Annan E. Assessment of human resources for pharmaceutical services in Ghana [Internet]. Pharmacy Council of Ghana, Ministry of Health, Ghana; 2009 [cited 2017 Jun 17]. Available from: assessment of human resources for pharmaceutical serviecs in ghana.

Gebretekle GB, Fenta TG. Assessment of pharmacists workforce in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2013;27(2):1–10.

Abuturkey DHY. Assessment of human resources at the pharmaceutical sector [Internet]. The Republic of the Sudan Federal Ministry of Health, Directorate General of Pharmacy; 2012. Available from: https://www.hrhresourcecenter.org/node/5018.html. Accessed Mar 2018.

Edwards P, Roberts I, Sandercock P, Frost C. Follow-up by mail in clinical trials: does questionnaire length matter? Control Clin Trials. 2004;25(1):31–52.

Iglesias C, Torgerson D. Does length of questionnaire matter? A randomised trial of response rates to a mailed questionnaire. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2000;5(4):291–21.

Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. 3rd ed. Berkshire: Open University Press; 2009. p. 525.

de Vaus D. Surveys in social research [Internet]. 5th ed. Taylor & Francis; 2002. 379 p. Available from: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1IRDJEtBg48C. Accessed Mar 2018.

Abosse Akue-Kpakpo, editor. Study on international internet connectivity in sub-Saharan Africa. A report of the Regulatory and Market Environment Division (RME) of the Telecommunication Development Bureau and ITU-T Study Group 3 [Internet]. International Telecommunication Union, Geneva, Switzerland; 2013 [cited 2017 Oct 12]. Available from: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Regulatory-Market/Documents/IIC_Africa_Final-en.pdf.

de Heer-Menlah FK. Internet access for African countries. Ubiquity. 2002;(4). Article No. 4. https://ubiquity.acm.org/article.cfm?id=763949. Accessed Mar 2018.

Olsen R. Self-selection bias. In: Lavrakas PJ, editor. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2008. p. 809–11.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Charles Ofei-Palm (Ghana), Onyimbo Kerama (Kenya), Prof. Sabiha Essack, Susan Buekes and GT Mahlatsi (South Africa), and Unoma Onugbolu and Kamilu Labaran (Nigeria) for their assistance with disseminating survey invite to pharmacists in their respective countries. We also thank the pharmacy leadership bodies in the countries represented in the survey for their interest in participating in our study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All authors had complete access to the data that supported the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IB conceived the study with inputs from AB and AU. AU designed the study, IB and AB provided input on methodology and reviewed interpretation of the outcome of the data analysis. All three authors read the draft manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was exempted from formal ethical approval by the research ethics committee as it did not involve the use of identifiable patient information or data, rather the study recruited pharmacists and sought their views by virtue of their professional roles.

Participants completed a consent page prior to participating in the survey.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Survey Questionnaire. (DOCX 63 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Udoh, A., Bruno, A. & Bates, I. A survey of pharmacists’ perception of foundation level competencies in African countries. Hum Resour Health 16, 16 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0280-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0280-1