Abstract

Background

Malaria and dengue fever are the leading causes of acute, undifferentiated febrile illness. In Africa, misdiagnosis of dengue fever as malaria is a common scenario. Through a systematic review of the published literature, this study seeks to estimate the prevalence of dengue and malaria coinfection among acute undifferentiated febrile diseases in Africa.

Methods

Relevant publications were systematically searched in the PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar until May 19, 2023. A random-effects meta-analysis and meta-regression were used to summarize and examine the prevalence estimates.

Results

Twenty-two studies with 22,803 acute undifferentiated febrile patients from 10 countries in Africa were included. The meta-analysis findings revealed a pooled prevalence of malaria and dengue coinfection of 4.2%, with Central Africa having the highest rate (4.7%), followed by East Africa (2.7%) and West Africa (1.6%). Continent-wide, Plasmodium falciparum and acute dengue virus coinfection prevalence increased significantly from 0.9% during 2008–2013 to 3.8% during 2014–2017 and to 5.5% during 2018–2021 (p = 0.0414).

Conclusion

There was a high and increasing prevalence of malaria and acute dengue virus coinfection in Africa. Healthcare workers should bear in mind the possibility of dengue infection as a differential diagnosis for acute febrile illness, as well as the possibility of coexisting malaria and dengue in endemic areas. In addition, high-quality multicentre studies are required to verify the above conclusions.

Protocol registration number: CRD42022311301.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute undifferentiated febrile illness (AUFI) is one of the most frequent reasons for seeking healthcare in Africa [1]. AUFI usually begins with nonspecific symptoms such as the sudden onset of fever, which rarely progresses to prolonged duration, headaches, chills, and myalgia, which may later involve specific organs. It can range from a mild and self-limiting illness to an advancing, deadly disease [2]. Malaria and dengue fever are leading causes of AUFI [3].

Africa carries the highest global malaria burden, with 2000 million cases (92%) in 2017 alone [4]. Human malaria is mainly caused by four Plasmodium species, namely, Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, and Plasmodium ovale, with a variable geographic distribution. P. falciparum accounts for nearly all malaria deaths in sub-Saharan Africa, which bears over 90% of the global malaria burden [5]. Likewise, the prevalence of dengue in the region has dramatically increased over the past few decades, although this specific infection is neither systematically investigated nor generally considered by clinicians [6]. In 2013, approximately 16 million apparent and over 48 million inapparent cases of dengue were estimated to have occurred, and most countries on the continent reported recurrent outbreaks [7]. Dengue fever is caused by four genetically distinct dengue viruses (serotypes 1–4) [8].

Although malaria or dengue virus monoinfections can be severe, concomitant infections could be even more fatal [9, 10]. The two mosquito-borne diseases have an overlapping epidemic pattern in Africa [11]. Similar main symptoms, such as fever, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, rash, nausea, diarrhoea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, are present in both of these illnesses [12]. Due to their similar clinical presentations, possible concurrent malaria-dengue fever is often neglected [13] and generally misdiagnosed as malaria only [6, 14]. Misdiagnosis is more probable during coinfection than mono-infection, and this may result in slow identification of dengue fever outbreaks with potentially high morbidity and mortality [6, 15].

A concurrent second infection may obscure the symptoms of either infection, and the treatment regimens for these co-infection are not the same as those for mono-infections [16], hence delaying the implementation of the appropriate treatment regimen or leading to serious complications [12, 16].

The highly mobile lifestyle of the population today, the increased activities made available by reliable global transportation networks, and climate change are anticipated to enhance the prevalence of co-infection with dengue and malaria [17]. This review aimed to gather evidence to answer how common could Plasmodium and dengue virus coinfection in Africa be? The specific review objective was to determine the prevalence of malaria and acute dengue coinfection in Africa (by region and study time period).

Methods

The protocol of the review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, PROSPERO (CRD42022311301), and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [18]. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data [19] was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Cross-sectional studies that reported Plasmodium and dengue virus coinfection among uncomplicated febrile cases attending health facilities in African regions were included. According to the United Nations, Africa is divided into five regions: Northern Africa, Central or Middle Africa, Southern Africa, East Africa, and Western Africa [20]. Similarly, the World Bank lists a total of 48 countries in the sub-Saharan African region [21].

Malaria might be diagnosed by malaria rapid diagnostic tests, microscopy and/or polymerase chain reaction, while dengue fever might be identified through an antigen or antibody test and/or reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Acute dengue or dengue fever was defined as positive for dengue IgM or NS1 antigen testing or RT‒PCR.

Reviews, grey literature, books, posters, conference proceedings, unpublished articles, articles whose full texts could not be obtained or were not available in English or that reported asymptomatic infections, studies of malaria without coinfection, reports of dengue without coinfection, case–control studies, experimental studies, reports of coinfection in malaria patients, reports of coinfection in dengue patients, and studies outside Africa were excluded. The primary outcome measure was the prevalence of malaria and dengue coinfections in Africa.

Databases and search strategy

The CoCoPop mnemonic (condition, context, and population) [22] was used to formulate the review question and systematically search all relevant studies from PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases until 19 May 2023. The search strategy used was as follows:

PUBMED

((("Malaria, Falciparum"[Mesh] OR "Malaria"[Mesh] OR "Plasmodium"[Mesh] OR "Plasmodium falciparum"[Mesh] OR malaria [tiab] OR falciparum [tiab] OR marsh fever [tiab] OR plasmodium [tiab] OR plasmodium falciparum [tiab]) AND ("Dengue"[Mesh] OR "Dengue Virus"[Mesh] OR dengue [tiab] OR dengue fever [tiab] OR breakbone fever [tiab] OR break bone fever [tiab] OR dengue virus*[tiab])) OR ((malaria [tiab] OR falciparum [tiab] OR plasmodium [tiab] OR marsh fever [tiab] OR plasmodium falciparum [tiab]) AND (dengue [tiab] OR dengue fever [tiab] OR breakbone fever [tiab] OR break bone fever[tiab] OR dengue virus*[tiab]) NOT MEDLINE[sb])) NOT systematic [sb].

Cochrane Library

ID | Search |

|---|---|

#1 | MeSH descriptor: [Malaria] explode all trees |

#2 | MeSH descriptor: [Plasmodium] explode all trees |

#3 | (malaria):ti,ab,kw OR (plasmodium):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) |

#4 | MeSH descriptor: [Dengue] explode all trees |

#5 | (dengue):ti,ab,kw OR (dengue fever):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) |

#6 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 |

#7 | #4 OR #5 |

#8 | #6 AND #7 |

Study quality appraisal and data extraction

The Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment, and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI) tool [23] was used to screen each article and extract relevant data for the review. Two of the authors (TT and JD) independently screened each article at the abstract and full-text levels. The discrepancy between the two reviewers was resolved through discussion. Articles endorsed in the full-text screening were subjected to the JBI critical appraisal tool. Those with good quality scores were subjected to data extraction. Data extraction included the first author’s last name, publication year, country/region of study, sample size, number of malaria and dengue coinfections, and demographic characteristics (age, gender) of patients with coinfections. The JBI criteria were used to score the quality of each study. Studies with a score greater than or equal to four were considered to have sufficient quality to be included in the meta-analysis.

Statistical analysis

The random-effect models was used to determine the prevalence estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q-test were used to measure the heterogeneity of the included studies, and meta-regression analysis was used to investigate the factors associated with heterogeneities in stratified meta-analyses. The publication bias was evaluated using Begg and Mezumdar rank correlation tests and assessed the relationship between malaria prevalence and dengue fever prevalence using spearman correlation. A subgroup analysis was performed to determine the prevalence by study time period and region and calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI of prevalence to estimate the effect of age and gender. A p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The data was analysed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis (Version 3) software.

Patient and public involvement

This study was performed without patient or public involvement.

Results

Literature retrieval and characteristics of the included studies

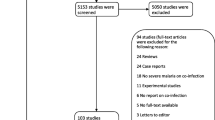

The article screening and selection process is depicted in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1). A total of 6661 records were identified during literature retrieval from the databases, and of those, 5431 had their titles and abstracts screened. The full texts of 22 studies involving 22,803 patients with AUFI were included in the quantitative synthesis [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] (Table 1). While 14 studies [29, 30, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] were carried out in or after 2015, eight [24,25,26,27,28, 31, 32, 45] of the included studies were conducted prior to that year. Nine of the included studies were carried out in Nigeria [24, 26, 27, 29, 30, 32, 35, 36, 38] and five in Cameroon [33, 34, 41, 42, 44], and the remaining eight studies were in Tanzania [25, 39], Kenya [31, 40], Senegal [28], Sierra Leone [45], Ethiopia [43], and the DRC [37]. All the included studies used a cross-sectional design and included patients with AUFI.

The range or interquartile rage (IQR) of age of participants was reported in 20 and two of the 22 studies, while the mean or median age were stated in 14 and six studies, respectively. The mean or median age was not mentioned in two studies [29, 45]. Eighteen studies included both children and adults, while four studies [25, 33, 40, 42] exclusively focused on children. Twenty studies were performed on both men and women. The gender of the participants was not specified in the two studies [31, 45]. Six studies [28, 35, 37, 41, 43, 44] used both RDT and microscopy; six studies used only standard microscopy [24, 25, 31, 32, 40, 42]; five studies [29, 33, 34, 38, 45] used only rapid diagnostic testing (RDT); two studies [30, 39] used only PCR; and one study [27] used both microscopy and PCR for malaria diagnosis. However, the detection method was not specified in one study [26].

The included studies’ JBI checklist scores varied from four to seven (Table 1). No study received a score of nine. Inappropriate sampling techniques (n = 15) and unstandardised outcome measurements (n = 10) were the most common methodological issues in the included studies.

Plasmodium falciparum and dengue virus coinfection

The random-effect model estimator was used in the meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of malaria and dengue coinfection in Africa was 42 (95% CI 30–60) per 1000 AUFI cases. This estimate substantially increased from 9 (95% CI 2–35) during 2008–2013 to 38 (95% CI 21–67) during 2014–2017 and then to 55 (95% CI 34–86) during 2018–2021 (Figs. 2 and 3). Between-study heterogeneity was found to be significantly high (I2 = 95.18; Q test p = 0.00), and no significant publication bias was observed (Kendall’s tau p = 0.176). The high degree of heterogeneity was significantly related to the study time period (p = 0.0414) (Table 2).

The prevalence of malaria-dengue coinfection across the three African regions ranges from 16 per 1000 febrile cases (95% CI 6–45) in West Africa to 27 (95% CI 7–97) in East Africa to 47 (95% CI 22–98) in Central Africa (Fig. 4).

The study time period was significantly related to the effect size (Table 2). In other words, the prevalence of malaria and acute dengue coinfection significantly increased over time.

The prevalence of Plasmodium and dengue virus coinfection was significantly higher in children than adults (Fig. 5; OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.27, 0.99, p = 0.047); however, there was no statistically significant difference between males and females (Fig. 6; OR = 0.85, 95% CI 0.54, 0.135, p = 0.503).

Association between malaria and dengue fever

A nonsignificant positive correlation (r = 0.128, p = 0.580) was observed between malaria and dengue fever prevalence among acute undifferentiated febrile illnesses (AUFI) in Africa during 2008–2021 continent-wide (Fig. 7). In all three regions, the correlation was not statistically significant. Interestingly, malaria prevalence was found to be higher than dengue in all three regions.

Discussion

Malaria has a complicated pathophysiology, causing pathologic alterations in all bodily systems. Direct red blood cell destruction and nonspecific inflammatory and immune responses are the major mechanisms involved [46]. Similarly, dengue virus infection involves a multi-organ system and is attributed to a complex interplay between the virus, host genes, and host immune response [47]. The dengue clinical spectrum includes asymptomatic infection, mild febrile sickness (dengue fever), and more severe presentations, including dengue shock syndrome and dengue haemorrhagic fever [48]. Clinical presentations of malaria and dengue are similar, with minor differences. For instance, malaria can be chronic, while dengue cannot. In addition, atypical lymphocytosis, haemoconcentration, and thrombocytopenia are strong predictors of dengue, whereas anaemia is a major symptom seen in malaria infections, which is a consequence of the merozoites (blood stages) causing intense intravascular haemolysis [13, 16].

Plasmodium and dengue virus coinfection occur when both of these mosquito-borne diseases occur simultaneously in an individual, which may increase the severity and duration of one or both [16]. The first report of malaria and dengue virus coinfection in Africa was documented in 2005 [15]. About 22,803 acute undifferentiated febrile patients were included from 22 studies conducted in 8 African countries (Senegal, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Cameroon, and the DRC) for approximately 13 years.

Based on the meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of malaria and dengue fever coinfection was 4.2%, and the highest rate was recorded in Central Africa (4.7%), followed by East Africa (2.7%) and West Africa (1.6%). This result is lower than the finding of a study [49] on a meta-analysis of severe malaria and dengue coinfections, which estimated a prevalence of 32%. The variation could be due to the differences in the study population, model estimator employed, and/or geography of the primary studies included, where the analysis was focused on studies from Africa while the other study included studies from all over the globe. In addition, uncomplicated febrile cases were included in the analysis, unlike the study above, which estimated severe malaria prevalence among the coinfections.

Across the African continent, the prevalence of co-infection with P. falciparum and dengue virus grew significantly from 0.9% between 2008 and 2013 to 3.8% between 2014 and 2017 and 5.5% between 2018 and 2021. This could be due to increased global transportation network dynamics, population movement, and climate change [17].

In the study, children were more affected by coinfection than adults. Children are more susceptible to mosquito-borne illnesses because they are exposed to mosquito bites for longer periods during dangerous hours [50]. Moreover, malaria [51] and dengue [52] mainly affect children due to their underdeveloped specific immunity to infection [51].

Furthermore, Plasmodium falciparum was the only malaria parasite specified in the coinfection among the included studies, as nearly all malaria cases in Africa are caused by P. falciparum [5].

The study showed a high and increasing trend of malaria and dengue coinfection prevalence in many parts of Africa. Nevertheless, healthcare workers misdiagnose dengue or malaria-dengue as malaria alone due to the institutionalisation of malaria as the primary febrile illness in the region by international development organizations and national malaria control programs [53], limited access to medical care and laboratory diagnostic facilities, a lack of awareness of healthcare workers towards non-malarial febrile illnesses [54], and the overlap of signs and symptoms of dengue with malaria [55]. Clinical misdiagnosis often leads to overuse or misuse of antimicrobials, which often accelerates the emergence and spread of antimicrobial drug resistance [56, 57]. On top of that, it causes mismanagement of the patient and dengue outbreaks [55]. Hence, the study calls for devising a standardised protocol for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with AUFIs, including dengue. In addition, healthcare professionals should always keep malaria and dengue infections in mind when dealing with such clinical presentations.

The study had some strengths and limitations. A large sample size, good-quality included studies, no evidence of publication bias among the included studies, and subgroup analysis were some of the strengths of the study; however, restriction to those published in English only, including single-centred facility-based studies, a small sample size in six studies [27, 29, 30, 34, 35, 39], and evidence of significant heterogeneity among the studies were some of the drawbacks of the study.

Conclusion

In general, a high prevalence of malaria and dengue virus coinfection among acute undifferentiated febrile patients was found in Africa, with variable rates across regions. Children were more affected by the coinfection than adults. Healthcare workers should bear in mind the possibility of dengue infection as one of the differential diagnoses for acute febrile illness, as well as the possibility of coexisting malaria and dengue in endemic areas. In addition, high-quality multicentre studies are required to verify the above conclusions and gain more insights into malaria and dengue virus coinfection on the continent.

Availability of data and materials

The study data are available on reasonable request. Interested researchers should contact the corresponding author using the email provided.

Change history

05 November 2023

This article has been corrected since original publication; please see the linked erratum for further details.

03 November 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04771-4

References

Escadafal C, Geis S, Siqueira AM, Agnandji ST, Shimelis T, Tadesse BT, et al. Bacterial versus non-bacterial infections: a methodology to support use-case-driven product development of diagnostics. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e003141.

Bhargava ARR, Chatterjee B, Bottieau E. Assessment and initial management of acute undifferentiated fever in tropical and subtropical regions. BMJ. 2018;363:k4766.

Prasad N, Murdoch DR, Reyburn H, Crump JA. Etiology of severe febrile illness in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0127962.

WHO. World malaria report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Snow RW, Omumbo JA. Disease and mortality in sub-saharan africa. In: Feachem RG, Jamison DT, Makgoba MW, Bos ER, Baingana FK, Hofman KJ, Rogo KO, editors. Chapter 14 Malaria. 2nd ed. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development The World Bank; 2006.

Gainor EM, Harris E, LaBeaud AD. Uncovering the burden of dengue in Africa: considerations on magnitude, misdiagnosis, and ancestry. Viruses. 2022;14:233.

Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–7.

WHO. Dengue and severe dengue. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue.

Epelboin L, Hanf M, Dussart P, Ouar-Epelboin S, Djossou F, Nacher M, et al. Is dengue and malaria co-infection more severe than single infections? A retrospective matched-pair study in french guiana. Malar J. 2012;11:142.

Ward DI. A case of fatal plasmodium falciparum malaria complicated by acute dengue fever in east timor. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:182–5.

Bygbjerg IC, Simonsen L, Schiøler KL. Elimination of falciparum malaria and emergence of severe dengue: an independent or interdependent phenomenon? Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1120.

Chong SE, Mohamad Zaini RH, Suraiya S, Lee KT, Lim JA. The dangers of accepting a single diagnosis: case report of concurrent Plasmodium knowlesi malaria and dengue infection. Malar J. 2017;16(1):2.

Wiwanitkit V. Concurrent malaria and dengue infection: a brief summary and comment. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2011;1:326–7.

Abdul-Ghani R, Mahdy MAK, Alkubati S, Al-Mikhlafy AA, Alhariri A, Das M, et al. Malaria and dengue in Hodeidah city, Yemen: high proportion of febrile outpatients with dengue or malaria, but low proportion co-infected. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0253556.

Charrel RN, Brouqui P, Foucault C, de Lamballerie X. Concurrent dengue and malaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1153–4.

Selvaretnam AAP, Sahu PS, Sahu M, Ambu S. A review of concurrent infections of malaria and dengue in asia. Asian Pacific J Trop Biomed. 2016;6:633–8.

Tatem AJ, Rogers DJ, Hay SI. Global transport networks and infectious disease spread. Adv Parasitol. 2006;62:293–343.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Chapter 5: systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Birjapur: JBI; 2020.

Pitt. African studies and African country resources. African studies program. University of Pittsburgh. 2022. https://pitt.libguides.com/.

World Bank. All countries of sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank. 2022. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/pages/focus-sub-saharan-africa.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–53.

JCI SUMARI End to end support for developing systematic reviews. 2022. https://sumari.jbi.global/.

Baba M, Logue CH, Oderinde B, Abdulmaleek H, Williams J, Lewis J, et al. Evidence of arbovirus co-infection in suspected febrile malaria and typhoid patients in Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7:51–9.

Chipwaza B, Mugasa JP, Selemani M, Amuri M, Mosha F, Ngatunga SD, et al. Dengue and chikungunya fever among viral diseases in outpatient febrile children in Kilosa district hospital. Tanzania PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3335.

Oyero OG, Ayukekbong JA. High dengue ns1 antigenemia in febrile patients in Ibadan. Nigeria Virus Res. 2014;191:59–61.

Ayorinde AF, Oyeyiga AM, Nosegbe NO, Folarin OA. A survey of malaria and some arboviral infections among suspected febrile patients visiting a health centre in Simawa, Ogun State Nigeria. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9:52–9.

Sow A, Loucoubar C, Diallo D, Ndiaye Y, Senghor CS, Dia AT, et al. Concurrent malaria and arbovirus infections in Kedougou. Southeastern Senegal Malar J. 2016;15:47.

Kolawole OM, Seriki AA, Irekeola AA, Bello KE, Adeyemi OO. Dengue virus and malaria concurrent infection among febrile subjects within Iorin Metropolis, Nigeria. J Med Virol. 2017;89:1347–53.

Miri MF, Mawak JD, Chukwu CO, Chuwang NJ, Acheng SY, Ezekiel T. Detection of IgM and IgG dengue antibodies in febrile patients suspected of malaria attending health centre in Jos Nigeria. Ann Med Lab Sci. 2017;1:27–35.

Obonyo M, Fidhow A, Ofula V. Investigation of laboratory confirmed dengue outbreak in north-eastern Kenya, 2011. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0198556.

Onyedibe K, Dawurung J, Iroezindu M, Shehu N, Okolo M, Shobowale E, et al. A cross sectional study of dengue virus infection in febrile patients presumptively diagnosed of malaria in Maiduguri and Jos Plateau Nigeria. Malawi Med J. 2018;30:276–82.

Tchuandom SB, Tchouangueu TF, Antonio-Nkondjio C, Lissom A, Djang JON, Atabonkeng EP, et al. Seroprevalence of dengue virus among children presenting with febrile illness in some public health facilities in Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;31:177.

Yousseu FBS, Nemg FBS, Ngouanet SA, Mekanda FMO, Demanou M. Detection and serotyping of dengue viruses in febrile patients consulting at the new-bell district hospital in Douala, Cameroon. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0204143.

Nassar SA, Olayiwola JO, Bakarey AS, Enyhowero SO. Investigations of dengue virus and Plasmodium falciparum among febrile patients receiving care at a tertiary health facility in osogbo, south-west Nigeria. Nigerian J Parasitol. 2019;40:18–24.

Otu AA, Udoh UA, Ita OI, Hicks JP, Egbe WO, Walley J. A cross-sectional survey on the seroprevalence of dengue fever in febrile patients attending health facilities in Coss River State. Nigeria PLoS One. 2019;14:e0215143.

Proesmans S, Katshongo F, Milambu J, Fungula B, Mavoko HM, Ahuka-Mundeke S, et al. Dengue and chikungunya among outpatients with acute undifferentiated fever in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo: a crosssectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007047.

Abdulaziz MM, Ibrahim A, Ado M, Ameh C, Umeokonkwo C, Sufyan MB, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with dengue fever among febrile patients attending secondary health facilities in Kano Metropolis Nigeria. African J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2020;21:340–8.

Ali MA, James OC, Mohamed AA, Joachim A, Mubi M, Omodior O. Etiologic agents of fever of unknown origin among patients attending Mnazi Mmoja Hospital Zanzibar. J Community Health. 2020;45:1073–80.

Shah MM, Ndenga BA, Mutuku FM, Vu DM, Grossi-Soyster EN, Okuta V, et al. High dengue burden and circulation of 4 virus serotypes among children with undifferentiated fever, Kenya, 2014–2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2638–50.

Galani BRT, Mapouokam DW, Simo FBN, Mohamadou H, Chuisseu PDD, Njintang NY, et al. Investigation of dengue-malaria coinfection among febrile patients consulting at ngaoundere regional hospital, Cameroon. J Med Virol. 2021;93:3350–61.

Nkenfou CN, Fainguem N, Dongmo-Nguefack F, Yatchou LG, Kameni JJK, Elong EL, et al. Enhanced passive surveillance dengue infection among febrile children: prevalence, co-infections and associated factors in Cameroon. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009316.

Akelew Y, Pareyn M, Lemma M, Negash M, Bewket G, Derbew A, et al. Aetiologies of acute undifferentiated febrile illness at the emergency ward of the university of gondar hospital. Ethiopia Trop Med Int Health. 2022;27:271–9.

Tchetgna HDS, Yousseu FS, Kamgang B, Tedjou A, McCall PJ, Wondji CS. Concurrent circulation of dengue serotype 1, 2 and 3 among acute febrile patients in cameroon. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;116(Supplement):S125.

Dariano DF, Taitt CR, Jacobsen KH, Bangura U, Bockarie AS, Bockarie MJ, et al. Surveillance of vector-borne infections (chikungunya, dengue, and malaria) in Bo, Sierra Leone, 2012–2013. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97:1151–4.

Autino B, Corbett Y, Castelli F, Taramelli D. Pathogenesis of malaria in tissues and blood. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4:e2012061.

Bhatt P, Sabeena SP, Varma M, Arunkumar G. Current understanding of the pathogenesis of dengue virus infection. Curr Microbiol. 2021;78:17–32.

Wang WH, Urbina AN, Chang MR, Assavalapsakul W, Lu PL, Chen YH, et al. Dengue hemorrhagic fever—a systemic literature review of current perspectives on pathogenesis, prevention and control. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:963–78.

Kotepui M, Kotepui KU. Prevalence and laboratory analysis of malaria and dengue co-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1148.

Quaresima V, Agbenyega T, Oppong B, Awunyo JADA, Adomah PA, Enty E, et al. Are malaria risk factors based on gender? A mixed-methods survey in an urban setting in Ghana. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021;6:161.

Schumacher RF, Spinelli E. Malaria in children. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4:e2012073.

Tantawichien T. Dengue fever and dengue haemorrhagic fever in adolescents and adults. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2012;32(s1):22–7.

Stoler J, Awandare GA. Febrile illness diagnostics and the malaria-industrial complex: a socio-environmental perspective. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:683.

Chipwaza B, Mugasa JP, Mayumana I, Amuri M, Makungu C, Gwakisa PS. Community knowledge and attitudes and health workers’ practices regarding non-malaria febrile illnesses in eastern tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2896.

Santos CY, Tuboi S, de de Jesus Lopes Abreu A, Abud DA, Lobao Neto AA, Pereira R, et al. A machine learning model to assess potential misdiagnosed dengue hospitalization. Heliyon. 2023;9:e16634.

Byrne MK, Miellet S, McGlinn A, Fish J, Meedya S, Reynolds N, et al. The drivers of antibiotic use and misuse: the development and investigation of a theory driven community measure. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1425.

Chokshi A, Sifri Z, Cennimo D, Horng H. Global contributors to antibiotic resistance. J Glob Infect Dis. 2019;11:36–42.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TTG designed the study, wrote the statistical analysis plan, monitored the review process, interpreted the data, cleaned and analysed the data, and wrote the draft manuscript. TG and JD assessed studies for inclusion. HS and ZM reviewed and commented on the draft paper. All authors have approved the final version. TTG is the guarantor and takes responsibility for the content of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study did not require ethical approval, as the data used have been published previously and hence are already in the public domain. Consent was not required when conducting a systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare; no support was obtained from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebremariam, T.T., Schallig, H.D.F.H., Kurmane, Z.M. et al. Increasing prevalence of malaria and acute dengue virus coinfection in Africa: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of cross-sectional studies. Malar J 22, 300 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04723-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-023-04723-y