Abstract

Background

The Viral hepatitis elimination by 2030 is uncertain in resource-limited settings (RLS), due to high burdens and poor diagnostic coverage. This sounds more challenging for hepatitis C virus (HCV) given that antibody (HCVAb) sero-positivity still lacks wide access to HCV RNA molecular testing. This warrants context-specific strategies for appropriate management of liver impairment in RLS. We herein determine the association between anti-HCV positivity and liver impairment in an African RLS.

Methods

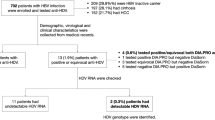

A facility-based observational study was conducted from July-August 2021 among individuals attending the “St Monique” Health Center at Ottou, a rural community of Yaounde,Cameroon. Following a consecutive sampling, consenting individuals were tested for anti-HCV antibodies, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and HIV antibodies (HIVAb) as per the national guidelines. After excluding positive cases for HBsAg and/or HIVAb, liver function tests (ALT/AST) were performed on eligible participants (HBsAg and HIVAb negative) and outcomes were compared according to HCVAb status; with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Out of 306 eligible participants (negative for HBsAg and HIVAb) enrolled, the mean age was 34.35 ± 3.67 years. 252(82.35%) were female and 129 (42.17%) were single. The overall HCVAb sero-positivity was 15.68%(48/306), with 17.86% (45/252) among women vs. 5.55%(3/54) among men [OR (95%CI) = 3.69(2.11-9.29),p = 0.04]. HCVAb Carriage was greater among participants aged > 50 years compared to younger ones [38.46%(15/39) versus 12.36% (33/267) respectively, OR(95%CI) = 4.43(2.11-9.29), p < 0.000] and in multipartnership [26.67%(12/45)vs.13.79%(36/261) monopartnership, OR (95%CI) = 2.27(1.07-4.80),p = 0.03]. The liver impairment rate (abnormal ALT+AST levels) was 30.39%(93/306), with 40.19%(123/306) of abnormal ALT alone. Moreover, the burden of Liver impairment was significantly with aged> 50 versus younger ones [69.23% (27/39) versus 24.72%(66/267) respectively, p < 0.000). Interestingly, the burden of liver impairment (abnormal AST + ALAT) was significantly higher in HCVAb positive (62.5%, 30/48) versus HCVAb negative (24.42%, 63/258) participants, OR: 3.90 [1.96; 7.79], p = 0.0001.

Conclusions

In this rural health facility, HCVAb is highly endemic and the burden of liver impairment is concerning. Interestingly, HCVAb carriage is associated with abnormal liver levels of enzyme (ALT/AST), especially among the elderly populations. Hence, in the absence of nuclei acid testing, ALT/AST are relevant sentinel markers to screen HCVAb carriers who require monitoring/care for HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in RLS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hepatitis C is a liver inflammation caused by a hepatitis C virus (HCV). This virus causes acute hepatitis that evolves in majority (85%) into chronic hepatitis [1]. Chronic hepatitis C is one of the main causes of cirrhosis and primary liver cancer. Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that an estimated 58 million people have chronic hepatitis C virus infection, with about 1.5 million new infections occurring per year [2]. In 2019, approximately 290,000 people died from hepatitis C, mostly from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [3]. In 2016, World Health Assembly has adopted the Global Health Sector Strategy (GHSS) on viral hepatitis to eliminate hepatitis by 2030 [4] However, available evidence demonstrates that global viral hepatitis elimination by 2030 is highly unlikely especially in Low and middle income countries where rates of hepatitis B and C diagnosis are very low, averaging 8 and 18%, respectively [5]. In fact, for HCV infection, 80% of high-income countries are not on track to meet HCV elimination targets by 2030, and 67% will not meet elimination targets even if they were given an additional 20 years [6]. In contrast to HBV, there is no prophylactic HCV vaccine [7].

In Cameroun, hepatitis C is endemic and the prevalence of HCV varies widely between 1 and 23.9% depending on the study population [8,9,10,11]. WHO and The Ministry of Public Health of Cameroon have made the fight against viral hepatitis their focus through vast treatment programs for hepatitis B/C and that have now been progressively made accessible to all social layer at low cost [12]. However, the lack of national Hepatitis C screening and treatment guidelines is reflected by a diversity in diagnostic and treatment protocols across care providers, resulting in unnecessary costs and possible sub-optimal clinical outcomes. Additionally, central organisation of Hepatitis C care, insufficient technical and human capacity for HCV testing, alongside high costs associated with diagnosis and treatment (generally paid out-of-pocket), substantially limit access to HCV diagnosis and care [13]. Most PLHCV in Cameroon are unaware of their status, with a negative impact on transmission and disease progression [14,15,16].

In community areas, in addition to the to lack of awareness on HCV, the problem is compound by low quality of health care, poverty and underdevelopment that constitute significant obstacles to early diagnosis and adequate management of HCV cases. In those settings, many HVCAb positive patients by rapid diagnostic test are either orientated for enrolment to a distant reference hospital center or requested an expensive and time-consuming HCV RT-PCR confirmatory test from a reference laboratory. This situation increases loss to follow-up of infectious patients with sustained HBV viral load who generally get back to health facilities afterwards with complications such as cirrhosis or hepatocellular cancer. Indeed, elevated HCV viral load is described to be consistently associated with high infectivity and risk of HCC occurrence [17,18,19]. Thus, much efforts should foster early identification and management of infected cases. Alanine Amino transferase (ALT) is a valuable liver enzyme test to detect otherwise inapparent liver disease [20]. Its elevation is considered as an indicator of Liver Damage [20] and could also predict viremia in anti-HCV-positive patients [21]. Besides, ALT measurement affords a readily available, low-cost blood test that is utilized throughout many countries as a tool for detection of liver disease [22] .

We conducted a mass screening of HCV in Ottou village-Yaounde that aimed at determining the association between HCVAb positivity and liver impairment in an African RLS.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

A cross-sectional study was conducted during a health campaign held from the 12 July to 12 August 2021 at the “Sainte Monique-Ngonmeda” Health Center, located at Ottou-village, at the periphery of Yaounde, center region of Cameroon. Ottou is a small village not so far from Yaounde and has been choosed for its hererogeneous population and for its geographical position with the presence of health center and a private medical laboratory capable to process ALT/AST biochemical test.

After getting required administrative authorization, consenting inhabitants of Ottou aged > 18 years, were enrolled consecutively at “Sainte Monique-Ngonmeda” Health Center for the health campaign. Each participant always had the choice either to participate only to the campaign or to both, the campaign and the study. Those who signed the informed consent, filled out the structured questionnaire in presence of a member of the team were included in the study. Conversely, those who declined the invitation and/or refused to sign the informed consent form could participate to the health campaign but were excluded from the study. Equally, participants who reported the use of oral plant extract were also excluded. From each participant included in the study, blood was collected onsite by a prick on the middle finger for a rapid detection of HCV antibodies, HIV antibodies and HBsAg. In parallel, 5 ml whole blood was also collected and stored in a cooler at + 4 °C before being transferred to the private laboratory “MEDIBIO-LAB” for ALT/AST dosage.

Given the current framework for HCV diagnosis, clinical and laboratory monitoring in our national health system, participant that were seropositive to HVCAb with or without abnormal ALT/AST level were directly linked to the General Hospital of Yaounde (the attached reference centre) for viral hepatitis management by a gastroenterologist according to national guidelines (prescription of HCV RNA by PCR, followed by either enrolment for treatment of PCR positive or referral for preventive service if PCR negative).

Determination of minimum sample size

The minimum sample size was obtained using the standard formula:

n = z2.p (1-p)/m2, with “z” = the standard deviation of 1.96 (95% confidence interval); “p” = Estimated nationwide seroprevalence of HCV in Cameroonians subjects aged > 15 years reported by Bigna et al. (6.5%) [8]; “m” = error rate of (5%) and “n” = minimum sample size.

Sample collection and conservation

Eligible participants who gave their approval were subjected to rapid diagnostic testing and blood collection for further testing (ALT/AST).

Blood sampling and rapid testing “on-site”

Blood was collected in aseptic conditions. In all, One drop of whole blood was required for the “on-site” testing for each rapid detection of HCV antibodies (Cypress diagnostics Technologies Inc., USA) HIV antibodies (Determine HIV 1/2; Alere Medical Co., Chiba, Japan) and HBsAg (DiaSpot HBsAg; DiaSpot Diagnostics, USA) according to the SOP /presented to us by the manufacturer. Cypress Diagnostics® HCV Rapid Antibody Test is rapid diagnostic test for the qualitative detection of HCV antibodies in serum and whole blood. Independent evaluation reported 96.7% (90.7–98.9%) sensitivity in whole blood [23] 97.8% (94.5–99.1%) specificity [23].

Samples transportation

Antibodies testing was performed on-site, whereas whole blood collected in dry tubes were transported to MEDIBIO-LAB, located not so far, for liver enzymes (ALT/AST) dosage. All blood samples were temporarily stored between 2 and 8 °C immediately after collection. And then, directly transferred to MEDIBIO-LAB and analyzed upon arrival.

Transaminases testing

Transminases (ALT, AST) were analysed from blood samples of HBsAg and HIVAb negative participants as described previously [24]. In Brief, after centrifugation 2000 rpm/min during 5 min, transaminases level were tested in each serum samples using an autoanalyzer. The level of ALT > 33 U/L and AST > 31 U/L for females and ALT > 40 U/L and AST > 37 U/L for males were classified as abnormal [24]. Laboratory quality control will be done regularly to verify inter- and intra-assay reproducibility.

Data analysis

The analyses were performed using the software package Stat view 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The continuous variables are presented in terms of mean ± Standard deviation (Std) and categorical variables in absolute number (proportion in %). Given that data on some variables were not properly recorded for all patients, we decided to include only participants with all information. The associations between HCVAb positivity or liver impairment and demographic and clinical characteristics were investigated by Chi-Square (Pearson or for trend), Mann–Whitney, or Kruskal-W,allis tests as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to identify factors independently associated with the risk of liver impairment and HCVAb carriage. For p < 0.05, the association was considered significant.

Limitations

This study was limited on antibody testing, and conducted to generate baseline finding at community-level on this topic.

So, one limitation of this study was the absence of HCV viral load due to limited funding. Moreover, some additional parameters (NAFLD or NASH, anthropometric measures) not taken into account in this study would have provided more insights on the relevance of our findings.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study population

The table 1 below presents the sociodemographic characteristics of the study population.

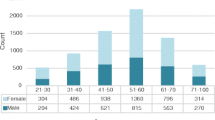

A total of 306 participants were surveyed between 12 July and 12 August 2021 at the “Sainte Monique-Ngonmeda” Health Center, Ottou-village, at the periphery of Yaounde Cameroon. In this study, the female participants were predominant with a percentage of 82.35% (n = 252), versus 17.65% (n = 54) for males participants with a sex ratio (F/M) of 5/1. The mean age was 34.52 ± 3.42 years [min 18, max 72] and subjects aged under 30 years were the most represented. Moreover, more than half (54.9%) of the participants were married, and 42.16% were single and 2.94% widowed. The majority of Participants declared to have the knowledge on the disease (83.33%) and only 3.92% had a history of blood transfusion. Regular use of condoms, HCV history in the neighborhood, multi-partnership, history of sexually transmitted infections and piercing were recorded in 6.86, 20.59, 14.71, 42.16 and 2.94% of the participants respectively. Lastly, 74.50% were alcohol consumers and none was illicit drug users. In this study, 90.20% of the participants had clinical signs of hepatitis C (see Table 1).

Prevalence of HCVAb and associated factors

This table below summarized the prevalence of HCVAb according to risk factors.

According to the hepatitis C antibody rapid detection tests results, participants who tested positive were 48 of the 306, for a prevalence 15.69% [11.58 - 19.78%]. The mean age of HCVAb positive was 36.25 ± 5.9 versus 31.21 ± 4.4 years for HCVAb negative individuals. Univariate analysis shows a higher seroprevalence of HCVAb in female subjects [17.86% vs. 5.55% men, OR (95%CI) = 3.69(2.11-9.29), p = 0.04], subjects aged > 50 years [OR(95%CI) = 4.43(2.11-9.29), p < 0.001], multipartnership [26.67% vs. 13.79% monopartnership, OR (95%CI) = 2.27(1.07-4.80), p = 0.03] and subjects who didn’t regularly sterilized their hairdressing materials [22.45% vs. 9.43%people sterilising theirs, OR (95%CI) = 2.78(1.44-5.36), p = 0.003] (see Table 2).

In multivariate analysis using logistic regression, only gender, age, multipartnership were found to be significantly associated to HCVAb carriage (p < 0.000).

Liver function of the study population

Prevalence of liver impairment

The Table 3 shows the Prevalence of liver impairment in the study population.

The prevalence of liver impairment (abnormal ALT+AST) was 30.39% (93/306) with 40.20% (123/306) of abnormal ALT (see Table 3).

Liver impairment according to risk factors

The Table 4 below shows liver impairment according to risk factors.

It comes out from Table 4 that liver impairment (abnormal ALT+AST level) was associated to Age (p = 0.01) with subject aged > 50 most affected as compared to younger ones [69.23% (27/39) versus 24.72% (66/267) respectively, p < 0.000).

Liver impairment according to hepatitis C antibodies carriage (HCVAb)

This table presents liver impairment according to hepatitis C antibodies carriage (HCVAb).

The prevalence of liver impairment (abnormal AST + ALAT) is much higher in HCVAb positive subjects (66.67% in positive subjects versus 33.87% in negative subjects, OR: 3.90 [1.96; 7.79], p = 0.0001). Besides, abnormal ALT level is also greater in HCVAb positive subjects than HCVAb negative (66.67%vs.35.27, OR: 3.67 [1.91; 7.05], p = 0.0001) (see Table 5).

Discussion

In order to investigate the association between HCVAb carriage and liver impairment in an African RLS, a facility-based observational study was conducted from July-August 2021 among individuals attending the “St Monique” Health Center, located at Ottou-village, a rural community of Yaounde, Cameroon. Following a consecutive sampling, consenting individuals were tested for anti-HCV antibodies, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and HIV antibodies (HIVAb) as per the national guidelines.

Among the 306 participants surveyed in Ottou-village, at the periphery of Yaounde Cameroon, female were predominant with a percentage of 82.35% (n = 252), versus 17.65% (n = 54) for males participants [sex ratio (F/M) 5/1]. The mean age was 34.52 ± 3.42 years [min 18, max 72] and subjects aged under 30 years were the most represented (50.98%). Kamga et al. in 2018 in the same study site reported a similar female predominance of 68.63% (105/153) and their mean age was 30.4 years ±5.63 years [25]. While several studies in community settings in Cameroon have also found similar women predominance trend [26,27,28,29], contrary results were more or less reported in rural area of foreign countries including Congo [30], Egypt [31], China [32], in the USA [33]. In fact, the Cameroonian demographics reflects in general more women than men and also a relative young population. However, this huge women’s predominance in this study could rely on daily activities in that community area where men in general are occupied in the farm while women takes care of the house and children, making them to be easily accessible for such health campaign. Globally, unlike men, women were likely much interested in health related matter. Furthermore, more than half (54.9%) proportion of the participants were married and the majority of participants declared having several sexual partners, having experienced a sexually transmitted infection once in their life already and not to regularly use condom. These results underscore the need of continuous sensitization of rural populations on the transmission routes of sexually transmitted diseases.

According to the hepatitis C antibody rapid detection tests results, participants who tested positive were 48 out of 306 (15.69%) [95% CI =11.58 - 19.78%]. HCVAb seroprevalence in Cameroon varies across regions and tribes within the same country. While some studies reported high HCVAb carriage: in the southern 12% [34], in the western 6.3% [35], numerous studies on the contrary revealed a relative much lower prevalence: 2.2% anti-HCV in the Northern [27], 0.6% in the eastern [36], 0.4% in the western [37], 4.8% in the Littoral Region [38], 1.44% in the center region [39]. Equally, various burden of anti-HCV antibodies have also been reported in community settings worldwide: 0.77% in Romania [40], 1.02% in Sudan [41], 1.2% in Madagascar [42], 2.4%in Iraq [43], 3.6% in India [44], 19.80% in Cairo [45]. It is known that anti-HCV seropositivity from population-based studies is used to compare levels of HCV infection [9]. According to WHO, countries in Africa and Asia have the highest rate of anti-HCV carriage, whereas industrialized countries in North America, Western Europe, and Australia are known to be lower endemic [46,47,48].

The prevalence of liver impairment (abnormal ASAT+ALAT) was 30.39% (93/306) with 40.20% (123/306) of abnormal ALAT. Similar studies in rural setting also portrayed high level of serum ALT: 7.1% in Uganda [49], 7.4%11.2% in Australia [50], 15% in China [51], 22.5% in North Indian [52]. Furthermore, Studies in the USA and Scandinavian revealed about 15% of chronic HCV among liver impaired participants presenting mild to moderate elevations of serum aminotransferase levels for at least 6 months [53, 54]. In fact, serum ALT measurement affords an easily accessible, low cost-effective blood test that is utilized throughout many countries as a liver disease detection tool [20]. ALT is considered as an Indicator of Liver Disease that could globally be used like a valuable screening test for inapparent liver disease, such as asymptomatic viral hepatitis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, that still remains largely undiagnosed worldwide [20, 21].

This study portrayed higher prevalence of abnormal level of both ALT + AST as well as abnormal ALT in anti-HCV positive as compared to anti-HCV negative (OR: 3.90 [1.96; 7.79], p = 0.0001 and OR: 3.67 [1.91; 7.05], p = 0.0001 respectively). Namme et al. in 2015 in Douala, Cameroon found 55.1% (246/444) of ALT above upper limit of normal among anti-HCV positive patients [20]. Also, Raheem et al. in Nigeria in 2021 found that ALT values were significantly elevated in HCV seropositivity [55]. Equally, Méndez-Navarro et al. in Mexico reported 82.6% (289/350) abnormal ALT vs. 17.4% (61/350) normal ALT in 350 consecutive patients with anti-HCV positive between 2003 and 2005 [56]. Many others findings reported higher elevated serum ALT level in anti-AHCV positive individual [57,58,59]. In fact, the screening for HCV is routinely strongly recommended in patients with elevated ALT levels and vice-versa [60]. On one side, HCVAb are a commonly available serological marker of HCV infection and on other side, it has been shown that high ALT is a marker for liver disease detection [61]. Chronic hepatitis C is likely associated with variable ALT levels, ranging from normal to high and it is reported that persistently normal levels of ALT in patients with hepatitis C correlates with good prognosis notably lower progression and occurrence of complications like cirrhosis [62]. Furthermore, even though an estimated proportion (25%) of HCV patients have persistently normal ALT levels [63], high ALT level remains an excellent tool in predicting viremia in anti-HCV-positive patients after excluding other causes of liver disease [8]. This study prompts the reinforcement of the follow up and management of anti-HCV positive individuals with high ALT level in community setting.

Conclusion

This study highlights a highly endemic HCVAb rate as well as a concerning burden of liver impairment in this rural health facility. Interestingly, HCVAb carriage is associated with abnormal liver levels of enzyme (ALT/AST), especially among the elderly populations. Hence, in the absence of nuclei acid testing, ALT/AST are relevant sentinel markers to screen HCVAb carriers who require monitoring/care for HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in RLS.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- AST:

-

Aspartate Aminotransferase

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B Surface Antigen

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- HCVAb:

-

Hepatitis C Antibody

- HCV RT-PCR:

-

Hepatitis C Virus Retrotranscriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction

- HIVAb:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Antibody

- PLHCV:

-

People Living with Hepatitis C

- MEDIBIO-LAB:

-

Medical Biology

- RLS:

-

Resource-Limited Setting

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Global surveillance and control of hepatitis C: report of a WHO consultation organized in collaboration with the viral hepatitis prevention board, Antwerp, Belgium. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:35–47. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2893.1999.6120139.x.

WHO. Hepatitis C, key fact. (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c, 24 June 2022, 19h).

Parsons G. Hepatitis C: epidemiology, transmission and presentation. Prescriber. 2022;33(6):20–3.

WHO. Global Health Sector Strategies on Viral Hepatitis 2016-2021. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_32-en.pdf?ua=1, accessed 09/07/2022.

Thomas DL. Global elimination of chronic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2041–50.

Razavi H, Sanchez Gonzalez Y, Yuen C, Cornberg M. Global timing of hepatitis C virus elimination in high-income countries. Liver Int. 2020;40:522–9.

World Health Organization. Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/206453/WHO_HIV_2016.04_eng.pdf/jsessionid=CADC5914BBC22D9F5FEBA9B2033892A3?sequence=1 (2016).

Bigna JJ, Amougou MA, Asangbeh SL, Kenne AM, Nansseu JR. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Cameroon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015748. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015748. PMID: 28851778; PMCID: PMC5724202.

Njouom R, Siffert I, Texier G, Lachenal G, Tejiokem MC, Pépin J, et al. The burden of hepatitis C virus in Cameroon: spatial epidemiology and historical perspective. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(8):959–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.12894. Epub 2018 Apr 14. PMID: 29533500.

Kowo M, Goubau P, Ndam E. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus and other blood-borne viruses in pygmies and neighbouring bantus in southern Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:484–6.

Tietcheu Galani BR, Njouom R, Moundipa PF. Hepatitis C in Cameroon: What is the progress from 2001 to 2016? J Transl Int Med. 2016;4(4):162–9. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtim-2016-0037. Epub 2016 Dec 30. PMID: 28191540; PMCID: PMC5290894.

World Health Organization, regional committee for Africa. Progress report on implementing the global health sector strategy for prevention, care and treatment of viral hepatitis 2016–2021 in the african region, Sixty-eighth session Dakar, Republic of Senegal, 27–31 August 2018 (https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2018-09/AFR-RC68-INF-DOC-6%20Progress%20report%20HEP%20strategy%202016-2021-Ed.pdf).

Marcellin F, Mourad A, Lemoine M, Kouanfack C, Seydi M, Carrieri P, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C in west and Central Africa (TAC ANRS 12311 trial). JHEP Reports. 2023;5(3):100665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhepr.2022.100665.

Chabrol F, Noah Noah D, Tchoumi EP, et al. Screening, diagnosis and care cascade for viral hepatitis B and C in Yaounde, Cameroon: a qualitative study of patients and health providers coping with uncertainty and unbearable costs. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025415.

Lemoine M, Eholie S, Lacombe K. Reducing the neglected burden of viral hepatitis in Africa: strategies for a global approach. J Hepatol. 2015;62:469–76.

Luma HN, Eloumou S, Noah DN, et al. Hepatitis C continuum of care in a treatment center in sub-Saharan Africa. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;8:335–41.

Boodram B, Hershow RC, Cotler SJ, Ouellet LJ. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and increases in viral load in a prospective cohort of young, HIV-uninfected injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119(3):166–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.005. Epub 2011 Jul 2. PMID: 21724339; PMCID: PMC3206181.

Kishta S, Tabll A, Omanovic Kolaric T, Smolic R, Smolic M. Risk factors contributing to the occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus patients treated with direct-acting antivirals. Biomedicines. 2020;8(6):175. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines8060175. PMID: 32630610; PMCID: PMC7344618.

El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(6):1264–1273.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. PMID: 22537432; PMCID: PMC3338949.3. World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 [cité 26 févr 2023]. 83 p. Disponible sur: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255016.

Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A, Torre ED, Butelli S, Vecchio ED, et al. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:1–9.

Espinosa M, Martin-Malo A, Alvarez de Lara MA, Soriano S, Aljama P. High ALT levels predict viremia in anti-HCV-positive HD patients if a modified normal range of ALT is applied. Clin Nephrol. 2000;54(2):151–6. PMID: 10968693.

Kim WR, Flamm SL, Di Bisceglie AM, Bodenheimer HC. Serum activity of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as an indicator of health and disease. Hepatology. 2008;47:1363–70. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22109.

Jargalsaikhan G, Eichner M, Boldbaatar D, Bat-Ulzii P, Lkhagva-Ochir O, Oidovsambuu O, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of commercially available rapid diagnostic tests for viral hepatitis B and C screening in serum samples. PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235036. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235036. PMID: 32667957; PMCID: PMC7363090.

Kenfack F, Nsagha DS, Assob JC. Abnormal liver function test in patients with diabetes and hypertension on treatment at the Laquintinie and Douala general. Hospitals. 2022;14(4):160–5. https://doi.org/10.5897/JPHE2020.1302. Article Number: DCF608169932. ISSN 2141-2316.

Rodrigue KW, Aimé KSL, Serges T, Nguwoh PS, Gaelle PT, Ibrahim MMK, et al. Prevalence of HIV and HBV and associated risk factors in communal areas: programmatic implications in the peripheral areas of Yaounde. International Journal of Health and Clinical Research. 2019;2(3) 14-20e-ISSN: 2590-3241, p-ISSN: 2590-325X.

Djuikoue CI, Kamga Wouambo R, Pahane MM, Demanou Fenkeng B, Seugnou Nana C, Djamfa Nzenya J, et al. Epidemiology of the acceptance of anti COVID-19 vaccine in urban and rural settings in Cameroon. Vaccines. 2023;11:625. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030625.

Njigou AR, Tochie JN, Danwang C, Tianyi F-L, Tankeu R, Aletum V, et al. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C Infections Mokolo District Hospital, Northern Cameroon: The Value of a Screening Campaign. Hosp Pract Res. 2018;3(3):79–84. https://doi.org/10.15171/hpr.2018.18.

Agbor VN, Tagny CT, Kenmegne JB, et al. Prevalence of anti-hepatitis C antibodies and its co-infection with HIV in rural Cameroon. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:459. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3566-4.

Ndifontiayong AN, Ali IM, Ndimumeh JM, Sokoudjou JB, Jules-Roger K, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C and associated risk factors among HIV-1 infected patients in a high risk border region of south West Cameroon. J Infect Dis Epidemiol. 2020;6:178. https://doi.org/10.23937/2474-3658/1510178.

Michel KN, Kennedy MN, Paul CM, Réne MJ, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among blood donors in general Dipumba Hospital in Mbujimayi, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Hepatol Gallblader Dis Research. 2018;2(1):1–4.

Abdel-Gawad M, Nour M, El-Raey F, et al. Gender differences in prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13:2499. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29262-z.

Gao Y, Yang J, Sun F, Zhan S, Fang Z, Liu X, et al. Prevalence of Anti-HCV Antibody Among the General Population in Mainland China Between 1991 and 2015: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(3):ofz040. https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofz040. PMID: 30863789; PMCID: PMC6408870.

Chan K, Mangla N. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection in the rural northeastern United States. Ann Hepatol. 2022;27(Supplement 1):100576, ISSN 1665-2681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aohep.2021.100576.

Adamu NN, Innocent MA, Jean BS, Jerimiah NM, Christopher BT. Seroprevalence of HBV/HCV-HIV Co-infections and Outcome After 24 months of HAART in HIV Patients, in Kumba Health District, Southwest Region of Cameroon. 2022- 4(4) OAJBS.ID.000468.

Nansseu JR, Mbogning DM, Monamele GC, et al. Sero-epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus: a cross-sectional survey in a rural setting of the west region of Cameroon. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2017;28:201. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2017.28.201.12717. PMID: 29610639; PMCID: PMC5878856.

Foupouapouognigni Y, Mba SA, Betsem A, Betsem E, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus infections in the three pygmy groups inCameroon. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(2):737–40. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01475-10.

Mbopi-Keou FX, Nkala IV, Kalla GC, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with HIV and viral hepatitis B and C in thecity of Bafoussam in Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:156. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.20.156.4571.28.

Noubiap JJ, Joko WY, Nansseu JR, Tene UG, Siaka C. Sero-epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis band C viruses, and syphilis infections among first-time blooddonors in Edea, Cameroon. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(10):e832–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2012.12.007.29.

Essome MC, Nsawir BJ, Nana RD, Molu P. Mohamadou M.[Sero-epidemiological study of three sexually transmitted infections: chlamydia trachomatis, hepatitis B, syphilis. Acase study conducted at the Nkoldongo District Hospitalin Yaounde]. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:244. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2016.25.244.11107.

Butaru AE, Gheonea DI, Rogoveanu I, Diculescu M, Boicea A-R, Bunescu M, et al. "Micro-elimination: updated pathway to global elimination of hepatitis C in small communities and industrial settings during the COVID 19 pandemic" journal of. Clinical Medicine. 2021;10(21):4976. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214976.

Mohamed Y, Doutoum A, Mahamat A, Doungous D, Gabbad A, Osmab R. Factors influencing hepatitis C viral infections in the population of Algamosi locality, Gezira state, Central Sudan. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines. 2022;10:332–9. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbm.2022.109023.

Ramarokoto CE, Rakotomanana F, Ratsitorahina M, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C and associated risk factors in urban areas of Antananarivo, Madagascar. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-8-25.

Al-Mahmood A, Al-Jubori A. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus among blood donors attending Samarra's general hospital. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2020;20(5):693–7. https://doi.org/10.2174/1871526519666190916101509. PMID: 31526354.

Trickey A, Sood A, Midha V, Thompson W, Vellozzi C, Shadaker S, et al. Clustering of hepatitis C virus antibody positivity within households and communities in Punjab. India Epidemiology & Infection. 2019;147:E283. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268819001705.

Anwar WA, El Gaafary M, Girgis SA, Rafik M, Hussein WM, Sos D, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and risk factors among patients and health-care workers of Ain Shams University hospitals, Cairo, Egypt. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246836. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246836. PMID: 33556152; PMCID: PMC7870060.

Karoney MJ, Siika AM. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Africa: a review. Pan Afr Med J. 2013; https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2013.14.44.2199.

Global surveillance and control of hepatitis C. Report of a WHO consultation organized in collaboration with the viral hepatitis prevention board, Antwerp, Belgium. J Viral Hepat. 1999;6:35–47.

Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:558–67.

O'Hara G, Mokaya J, Hau JP, Downs LO, McNaughton AL, Karabarinde A, et al. Liver function tests and fibrosis scores in a rural population in Africa: a cross-sectional study to estimate the burden of disease and associated risk factors. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e032890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032890. PMID: 32234740; PMCID: PMC7170602.

Mahady SE, Gale J, Macaskill P, Craig JC, George J. Prevalence of elevated alanine transaminase in Australia and its relationship to metabolic risk factors: a cross-sectional study of 9,447 people. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(1):169–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.13434. PMID: 27144984.

Chen Y, Chen Y, Geng B, Zhang Y, Qin R, Cai Y, et al. Physical activity and liver health among urban and rural Chinese adults: results from two independent surveys. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2021;19(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2020.07.004. Epub 2020 Jul 28. PMID: 32904178; PMCID: PMC7452301.

Asadullah M, Shivashankar R, Shalimar KD, Kondal D, Rautela G, Peerzada A, et al. Rural-Urban differentials in prevalence, spectrum and determinants of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in North Indian population. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0263768. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263768. PMID: 35143562; PMCID: PMC8830644.

Kundrotas L, Clement D. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation in asymptomatic US air Force basic trainee blood donors. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;39:2145–50.

Mathiesen U, Franzen L, Fryden A, Foberg U, Bodemar G. The clinical significance of slightly to moderately increased liver transaminase values in asymptomatic patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:85–91.

Raheem T, Orukpe-Moses M, Akindele S, Wahab M, Ojerinola O, Akande D, et al. Age, gender pattern and liver function markers in hepatitis B and C seropositive participants attending a Health Facility in Yaba-Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Biosciences and Medicines. 2021;9:44–58. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbm.2021.97007.

Méndez-Navarro J, Dehesa-Violante M. Does the persistently normal aminotransferase levels in hepatitis C still have relevance? Ann Hepatol. 2012;11(3):412–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1665-2681(19)30941-X.

Pradat P, Alberti A, Poynard T, Esteban J-I, Weiland O, Marcellin P, et al. Predictive value of ALT levels for histologic Findingsin chronic hepatitis C: a European collaborative study. Hepatology. 2002;36(4).

Cassidy MJ, Jankelson D, Becker M, Dunne T, Walzl G, Moosa MR. The prevalence of antibodies to hepatitis C virus at two haemodialysis units in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 1995;85(10):996–8. PMID: 8596992.

Juan Ignacio Esteban, Juan Carlos López-Talavera, Juan Genescà, Pedro Madoz, Luis Viladomiu, Eduardo Muñiz, Carmen Martin-Vega, Manuel Rosell, Helena Allende, Xavier Vidal, Antonio González, Jose Manuel Hernández, Rafael Esteban, Jaime Guardia, High Rate of Infectivity and Liver Disease in Blood Donors with Antibodies to Hepatitis C Virus, Articles15 September 1991. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-115-6-443.

Grad R, Thombs BD, Tonelli M, Bacchus M, Birtwhistle R, Klarenbach S, et al. Recommendations on hepatitis C screening for adults. CMAJ. 2017;189(16):E594–604. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.161521. PMID: 28438952; PMCID: PMC5403642.

Coppola N, Pisaturo M, Zampino R, Macera M, Sagnelli C, Sagnelli E. Hepatitis C virus markers in infection by hepatitis C virus: in the era of directly acting antivirals. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(38):10749–59. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10749. PMID: 26478667; PMCID: PMC4600577.

Woreta TA, Alqahtani SA. Evaluation of abnormal liver tests. Med Clin N Am. 2014;98:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2013.09.005.

Dienstag JL, Alter HJ. Non-a, non-B hepatitis: evolving epidemiologicand clinical perspective. Semin Liver Dis. 1986;6:67–81.

Acknowledgements

We hereby would like to thank all participants, Health personnel of “Sainte Monique-Ngonmeda” Health Center and MEDIBIO-Laboratory.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed the study: RKW, GPT, LAKS, EPTL, DB, JF; Planned and performed the experiments: RKW, GPT, DPDD, GFMT, DB; Analysed and interpreted the data: GPT, DPDD, CIYW; Initiated the manuscript: RKW, GPT, LAKS, DPDD, CIYW, DB, JF; Revised the manuscript: All the authors; Approved the final version of the manuscript: All the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research proposal was evaluated and ethical clearance was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee for Research involving Humans of the Center Region Cameroon (CRERSHC, N°: CE01132/CRERSHC, on May 10th, 2021). Additionally, we obtained administrative authorization from the directors of “Sainte Monique” Health Center (Ref N°115/2021/CSGPSM/RS) and MEDIBIO-LAB (N°2021/10/MEDIBIO-LAB/LR) where the study was conducted. An information note was given to all the eligible participants, who then provided their written informed consent before enrollment into the study. The confidentiality of study participants was secured via the use of identification codes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kamga Wouambo, R., Panka Tchinda, G., Kagoue Simeni, L.A. et al. Anti-hepatitis C antibody carriage and risk of liver impairment in rural-Cameroon: adapting the control of hepatocellular carcinoma for resource-limited settings. BMC Infect Dis 23, 875 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08880-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-023-08880-y