Abstract

Background

Streptococcus oralis belongs to the Streptococcus mitis group and is part of the normal flora of the nasal and oropharynx (Koneman et al., The Gram-positive cocci part II: streptococci, enterococci and the ‘Streptococcus-like’ bacteria. Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology, 1997). Streptococcus oralis is implicated in meningitis in patients with decreased immune function or from surgical manipulation of the central nervous system. We report a unique case of meningitis by Streptococcus oralis in a 58-year-old patient with cerebral spinal fluid leak due to right sphenoid meningoencephalocele.

Case presentation

A 58-year-old female presented in the emergency department due to altered mental status, fevers, and nuchal rigidity. Blood cultures were positive for Streptococcus oralis. Magnetic resonance stereotactic imaging of head with intravenous gadolinium showed debris in lateral ventricle occipital horn and dural thickening/enhancement consistent with meningitis. There was also a right sphenoidal roof defect, and meningoencephalocele with cerebrospinal fluid leak as a result. The patient was treated with ceftriaxone and had endoscopic endonasal repair of defect. She had complete neurologic recovery 3 months later.

Conclusions

Cerebrospinal fluid leak puts patients at increased risk for meningitis. Our case is unique in highlighting Streptococcus oralis as the organism implicated in meningitis due to cerebrospinal fluid leak.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Streptococcus oralis is a member of Streptococcus mitis family and belongs to the Viridans group. The organism is part of the normal flora of the nasal, oropharyngeal, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts [1]. The species usually presents with low pathogenicity and virulence [1]. There are case studies of Streptococcus oralis causing meningitis in individuals with decreased immune function and with anatomic manipulation of the central nervous system. These include cases caused by increased alcohol use [2], leukemia [3], spinal anesthesia [4], and neurologic surgeries [2]. Streptococcus oralis has caused meningitis in those with surgical manipulation of the dental cavity as well due to the anatomical location of the organism and propensity to cause meningitis in individuals [5, 6].

Cerebrospinal fluid leaks place patients at increased risk for meningitis. A retrospective study analyzing 111 patients with proven CSF leak from endoscopy, beta-2 transferrin, imaging, and/or fluorescein lumbar puncture had risk of meningitis of 19% over 12 years [7].. The most common organism implicated in meningitis from cerebrospinal fluid leaks is Streptococcus pneumoniae [7]. We present a unique case of acute meningitis due to Streptococcus oralis extending from sinusitis in a 58-year-old female with a right sphenoid meningoencephalocele. She had herniation of right temporal lobe through the sphenoidal roof defect with subsequent cerebrospinal fluid leak. MRI imaging of brain showed meningeal enhancement and ventricular debris, highly concerning for meningitis. CT head non-contrast showed herniation. Lumbar puncture was contraindicated. Guidelines from Infectious Disease Society of America in diagnosing bacterial meningitis include blood cultures and computed tomography scan of the head without contrast in select populations to evaluate for any contraindications to lumbar puncture [8]. Those with contraindications and high likelihood for meningitis are treated with targeted antibiotics based on blood culture results [8]. In these difficult diagnosis, MRI of the head can show meningeal enhancement and ventricular debris with high sensitivity and specificity [9].

Case presentation

A 58-year-old female presented to the emergency department due to severe headaches, altered mental status with minimal response, neck stiffness, and fever of 38.3 C. She was not alert or oriented to person, place, or time. She was arousable with sternal rub and did track to visual stimuli. Per family members, these signs and symptoms started 1 day prior to admission. Her past medical history was significant for right sphenoid meningoencephalocele with herniation of the right temporal lobe through a defect in the roof of the sphenoid recess. This was never surgically addressed in the past. She never had trauma to the skull, tumors, or mass lesions in the brain before. She also had meningitis 10 years prior that was treated with an unknown antibiotic course as well as a history of sinusitis and clear nasal drainage that was worse with leaning forward for 3 months in duration. The patient denied sick contacts and recent travel. On admission (Day 0), her white blood cell count was 28.5 cubic milliliter (reference range 3.8–10.5 cubic milliliter), with a neutrophil predominance of 91%.

On day 0, 2 sets of anaerobic and aerobic blood cultures were obtained. Chlorhexidine was used as an antiseptic on the right antecubital region and venous blood was obtained for one set of aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures. A second set of blood cultures were taken within 1 h. Aerobic cultures were collected first with Aerobic Bactec plus culture vials from Becton, Dickinson, and Company. 10 ml were obtained for each bottle. Anaerobic cultures were collected second with Bactec lytic anaerobic culture vials by Becton, Dickinson, and Company. 10 ml were obtained for each bottle. There was no manipulation of the oral cavity prior to these culture sets. Urinalysis was negative for signs of urinary tract infection. Chest x-ray was negative for signs of pneumonia.

On day 0, MR of orbit, face, and neck with and without intravenous gadolinium contrast showed right sphenoid meningoencephalocele with herniation of the right temporal lobe as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. There was meningeal enhancement and ventricular debris present. Lumbar puncture was contraindicated secondary to prior herniation, but on day 7 magnetic resonance stereotactic imaging of head with intravenous gadolinium showed debris in lateral ventricle occipital horn and dural thickening/enhancement consistent with meningitis. Her neck stiffness, altered mental status, and fevers were also consistent with meningitis [8]. On admission, empiric coverage with vancomycin 1 g every 12 h, ceftriaxone 2 g every 12 h, and ampicillin 2 g every 6 h was initiated based on guidelines, in addition to dexamethasone 2 g every 2 h [8].

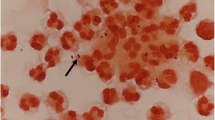

On day 1, both sets of aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles had giemsa staining that was positive for gram positive cocci in pairs and chains. All four culture bottles grew Streptococcus oralis. The isolate was susceptible to penicillin and ceftriaxone. On day 2, vancomycin and ampicillin were discontinued. By day 4, patient slowly regained mental status. On day 5, white blood cell count was 9.5 cubic milliliter (reference range 3.8–10.5 cubic milliliter). On day 5, beta 2 transferrin from nasal secretions were positive, confirming cerebrospinal fluid leak. Despite ceftriaxone therapy, patient continued to have low grade fevers from admission to day 4.

Transesophageal echocardiogram was performed to rule out endocarditis. No vegetations were observed. Otolaryngologist were consulted. On day 7, patient had endonasal endoscopic repair of roof of the sphenoid bone was performed. She improved clinically through her hospital course with resolution of mental status to her baseline. Three months later she had no complications as a result. Magnetic resonance imaging of brain without contrast after 1 month of treatment was negative for brain herniation, and patient remained afebrile without complication.

Discussion and conclusions

Meningitis can be potentially devastating if not diagnosed and treated early. Patients with CSF leaks are at an increased risk for meningitis. This population can be difficult to diagnose meningitis if there are contraindications to lumbar punctures. Based on Infectious Disease Society of America, blood cultures should be collected first [8]. CT scan should be performed next, and if there are contraindications to lumbar puncture and a high clinical likelihood for meningitis, antibiotics must be administered as soon as possible [8]. In this scenario, antibiotics must target the organism collected form blood cultures [8].

Magnetic resonance imaging with intravenous gadolinium and fluid attenuated inversion recovery has high sensitivity and specificity for meningitis based on meningeal enhancement [9, 10]. Streptococcus oralis has not been implicated in meningitis from cerebrospinal fluid leaks in the literature. Risks of meningitis from chronic CSF leaks over 12 years are 19% and carry a high morbidity and mortality [7]. Beta 2 transferrin is a useful adjuvant in helping clinicians diagnose CSF leaks, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 99% [11,12,13].

It is important for clinicians to suspect cerebrospinal fluid leak in those with altered mental status due to concern for spread of local organisms causing meningitis. Prompt antibiotics and surgical management are paramount in preventing morbidity and mortality [9]. It is important to rule out infective endocarditis because Streptococcus oralis has propensity to cause this disease burden [7]. Our case highlights that defects in the sphenoidal roof with meningoencephalocele can predispose patients to meningitis from Streptococcus oralis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Koneman EW, Allen SD, Janda WM, Schreckenberger PC, Win WC. The Gram-positive cocci part II: streptococci, enterococci and the ‘Streptococcus-like’ bacteria. Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 5th. New York: Lippincott; 1997. 577-649.

Kutlu SS, Sacar S, Cevahir N, Turgut H. Community-acquired Streptococcus mitis meningitis: a case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(6):107–9.

Jaing T, Chiu C, Hung I. Successful treatment of meningitis caused by highly-penicillin-resistant Streptococcus mitis in a leukemic child. Chang Gung Med J. 2002;25(3):190–3.

Willder J, Michelle RK, Sutcliffe N, Siegmeth A. Streptococcus oralis meningitis following spinal anaesthesia. Anaesth Cases. 2013:2013–0092. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2396-8397.2013.tb00020.x.

Montejo M, Aguirrebengoe K. Streptococcus oralis meningitis after dental manipulation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:126–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1079-2104(98)90413-9.

Cabellos C, Viladrich P, Corredoira J, Verdaguer R, Ariza J, Gudiol F. Streptococcal Meningitis in Adult Patients: Current Epidemiology and Clinical Spectrum. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1104–8. https://doi.org/10.1086/514758.

Daudia A, Biswas D, Nick SJ. Risk of Meningitis with Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;116:902–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940711601206.

Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, Kaufman BA, Roos KL, Scheld WM, Whitley RJ. Practice Guidelines for the Management of Bacterial Meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(9):1267–84. https://doi.org/10.1086/425368.

Aneel KV, Nizamani W, Ali M, Aneel G, Kumar B, Hussain S. Diagnostic Accuracy of Contrast-Enhanced FLAIR Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Diagnosis of Meningitis Correlated with CSF Analysis. ISRN Radiology. 2014;2014:578986. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/578986.

Kamra P, Azad R, Prasad K, Jha S, Pradhan S, Gupta RK. Infectious meningitis: Prospective evaluation with magnetization transfer MRI. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:387–94. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/23641059.

Warnecke A, Averbeck T, Wurster U, Harmening M, Lenarz T, Stöver T. Diagnostic Relevance of β2-Transferrin for the Detection of Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistulas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1178–84. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.130.10.1178.

Safavi A, Safavi AA, Jafari R. An empirical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea: an optimised method for developing countries. Malays J Med Sci. 2014;21:37–43.

Chan DT, Poon WS, Ip CP, Chiu PW. Goh KY. How useful is glucose detection in diagnosing cerebrospinal fluid leak? The rational use of CT and Beta-2 transferrin assay in detection of cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Asian J Surg. 2004;27:39–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Internal Medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital for guidance on this case.

Funding

No sources of funding for this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KP, DO: Writing a draft and final edit of the manuscript. Analyzed relevant research and articles in the database. ZM, DO: Involved in final edits of the manuscript. Helped with relevant data analysis. Helped find relevant articles relating to the case. AP, MD: Involved in final edits of the manuscript. Helped with organization of the paper. CP, MD: Helped in critical analysis of the paper and analyzed the radiologic images. AS: Involved in final edits of the manuscript. Helped organize and find relevant sources. NI: Involved in the final edits of the manuscript, helped in analyzing the data, and involved in finding appropriate sources. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics from Northwell Health Lenox Hill Hospital committee.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, K., Memon, Z., Prince, A. et al. Streptococcus Oralis meningitis from right sphenoid Meningoencephalocele and cerebrospinal fluid leak. BMC Infect Dis 19, 960 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4472-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4472-7