Abstract

Background

The WHO guidelines for the management of advanced HIV disease recommend a package of care consisting of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), enhanced screening and diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) and cryptococcal meningitis, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT), fluconazole pre-emptive therapy, and adherence support. The goals of this study were to determine the prevalence of advanced HIV disease among individuals initiating ART in Senegal, to identify predictors of advanced disease, and to evaluate adherence to the WHO guidelines.

Methods

This study was conducted among HIV-positive individuals initiating ART in Dakar and Ziguinchor, Senegal. Clinical evaluations, laboratory analyses, questionnaires and chart review were conducted. Logistic regression was used to identify predictors of advanced disease.

Results

A total of 198 subjects were enrolled; 70% were female. The majority of subjects (71%) had advanced HIV disease, defined by the WHO as a CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3 or clinical stage 3 or 4. The median CD4 count was 185 cells/mm3. The strongest predictors of advanced disease were age ≥ 35 (OR 5.80, 95%CI 2.35–14.30) and having sought care from a traditional healer (OR 3.86, 95%CI 1.17–12.78). Approximately one third of subjects initiated ART within 7 days of diagnosis. Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis was provided to 65% of subjects with CD4 counts ≤350 cells/mm3 or stage 3 or 4 disease. TB symptom screening was available for 166 subjects; 54% reported TB symptoms. Among those with TB symptoms, 39% underwent diagnostic evaluation. Among those eligible for IPT, one subject received isoniazid. No subjects underwent CrAg screening or received fluconazole to prevent cryptococcal meningitis.

Conclusions

This is the first study to report an association between seeking care from a traditional healer and presentation with WHO defined advanced disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Given the widespread use of traditional healers in sub-Saharan Africa, future studies to further explore this finding are indicated. Although the majority of individuals in this study presented with advanced disease and warranted management according to WHO guidelines, there were numerous missed opportunities to prevent HIV-associated morbidity and mortality. Programmatic evaluation is needed to identify barriers to implementation of the WHO guidelines and enhanced funding for operational research is indicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Progress towards reducing AIDS-related deaths in Western and Central Africa lags behind other regions. Nearly one third of global HIV-related deaths occur in Western and Central Africa, and although globally HIV-related deaths have declined by 34%, deaths in Western and Central Africa have declined by only 24%, from 370,000 in 2010 to 280,000 in 2017 [1]. According to UNAIDS estimates, only 48% of people living with HIV (PLHIV) in Western and Central Africa know their status, indicating a substantial regional gap in achieving the first of the 90–90-90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic [2]. Delayed diagnosis contributes to ongoing presentation with advanced HIV disease and HIV-associated mortality.

Despite efforts to improve access to HIV testing and treatment, approximately one third of individuals with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) present with advanced disease [3,4,5]. In West Africa specifically, more than half of PLHIV present with advanced disease. The median CD4 count at ART initiation is 186 cells/mm3, which is lower than other regions on the continent and is indicative of severe immunodeficiency and susceptibility to opportunistic infections [3].

In 2017, the WHO published guidelines recommending a package of targeted interventions to reduce morbidity and mortality among people presenting with advanced HIV [6]. The guidelines describe a package of care which includes rapid initiation of ART, enhanced screening and diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB) and cryptococcal meningitis (CM), co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT), and fluconazole pre-emptive therapy. The goals of this study were to determine the prevalence of advanced disease among individuals initiating ART in Senegal, West Africa, to identify predictors of advanced disease, and to evaluate adherence to the WHO guidelines for the management of advanced HIV disease.

Methods

This study was conducted at HIV testing and treatment sites located at the Centre Hospitalier National Universitaire de Fann (Centre Régional de Recherche et de Formation à la Prise en Charge Clinique de Fann) in Dakar and the Centre de Santé de Ziguinchor, located in Ziguinchor. Dakar is the urban capital of the country, while Ziguinchor is located in the southern Casamance region. All HIV-positive individuals initiating ART through the Senegalese National AIDS program (ISAARV) who provided written informed consent were eligible for enrollment. For subjects < 18 years of age, consent was obtained from their legal guardian. Subjects were enrolled sequentially from April 2017 to April 2018. Study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and the Senegal Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CNERS).

Study encounters were conducted in the participant’s preferred language, including French, Wolof, Diola, Peular, Mandinka, or Creole. Sociodemographic characteristics were determined using interviewer administered questionnaires. Food insecurity was determined using the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale [7]. WHO clinical staging was determined by clinical evaluation and chart review [8]. A review of systems was performed during clinical evaluation. Laboratory testing was conducted to determine HIV type and to measure CD4 cell count. Days until ART initiation was calculated by subtracting the date of ART initiation from the date of HIV diagnostic testing. Medical records were reviewed to capture clinical presentation, medical history, diagnostic testing, and medications prescribed.

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM, Armonk, N.Y.). Descriptive analysis was performed for all variables. Logistic regression was used to identify predictors of presentation with advanced disease. Variables identified in the literature as associated with advanced disease were evaluated using simple regression, Variables which were predictive using simple regression were included in the multiple regression model. Missing data were excluded from analysis. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

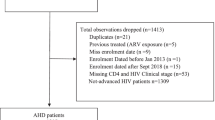

A total of 198 subjects were enrolled, 83 (42%) in Dakar and 115 (58%) in Ziguinchor (Table 1). This represents 65% of the 303 individuals that initiated ART at the study sites during the study period. The majority of subjects (89%) were infected with HIV-1, including two HIV-1/HIV-2 dually infected subjects, and 21 (11%) were infected solely with HIV-2. More than two thirds of subjects (70%) were female. Approximately 58% of subjects were ≥ 35 years of age. Nearly two thirds reported that they live in either the County of Dakar or the County of Ziguinchor. Nearly one third (31%) had no formal education and only 29% had ever attended secondary school. The median number of children per subject was 2, with a range of 0–10. Most subjects were married, 39% were in monogamous marriages and 16% were in polygamous marriages. Only 14% of subjects were employed and the majority (69%) were food insecure. One third reported seeking care from a traditional healer prior to presentation.

CD4 cell counts were available for 185 subjects (Table 2). The median CD4 count at presentation was 185 cells/mm3, with a range of 1–1541. The median CD4 cell count differed among those who were infected with HIV-1 versus those were infected solely with HIV-2 (170 cells/mm3 vs. 412 cells/mm3, p = 0.03). Nearly three quarters of subjects presented with a CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm3, 55% presented with < 200 cells/mm3, 36% had < 100 cells/mm3, and 20% had < 50 cells/mm3. WHO clinical staging was available for 167 subjects, of which 53% had WHO stage 3 or 4 disease. The most common WHO stage 3 conditions were severe weight loss, chronic diarrhea, oral candidiasis, and pulmonary TB. The most common WHO stage 4 condition was extra-pulmonary TB. The majority of subjects (71%) had advanced HIV disease, defined by the WHO as a CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3 or stage 3 or 4 disease.

Variables which were predictive of advanced disease using simple regression included male sex, age ≥ 35, and having sought care from a traditional healer prior to presentation (Table 3). Clinic site, residence in Dakar or Ziguinchor, education, number of children, marital status, employment status, and food insecurity were not associated with advanced disease. In the multiple regression model, age ≥ 35 (OR 5.80, 95% CI 2.35–14.30) and having sought care from a traditional healer prior to presentation (OR 3.86, 95% CI 1.17–12.78) were predictive of advanced disease.

The most frequently prescribed antiretrovirals were tenofovir (TDF) (95%), lamivudine or emtricitabine (3TC or FTC) (100%), and efavirenz (EFV) (84%) (Table 4). One HIV-2 infected subject received efavirenz. Twenty-one subjects received lopinavir/ritonavir including 18 HIV-2 infected subjects, 1 dually infected subject receiving TB treatment during an abacavir (ABC) stock-out, and 2 non-pregnant adults with HIV-1 infection. Integrase inhibitors were not available. Among those with no known active TB or CM, 34% initiated ART within 7 days of diagnosis. Among those with advanced disease, 38% initiated ART within 7 days of diagnosis. Co-trimoxazole prescription data were available for 157 subjects. Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis was provided to 53% of all subjects and 65% of subjects with CD4 counts ≤350 cells/mm3 or stage 3 or 4 disease. In one case, a co-trimoxazole stock-out was reported. A review of symptoms was available for 166 subjects, 77 (46%) did not report symptoms consistent with TB (fever, cough, weight loss, night sweats) and 89 (54%) reported symptoms consistent with TB. Among those without TB symptoms, 4 had extra-pulmonary TB, resulting in 73 (44%) of subjects eligible for IPT. Among those eligible for IPT, one subject (1%) received a 2 week prescription for INH. Among those with TB symptoms, only 35 (39%) underwent diagnostic evaluation, 31 were evaluated by microscopy for acid-fast bacilli using Ziehl-Neelsen staining and 10 were evaluated by Xpert® MTB/RIF (Cepheid). There was no rifampicin resistance detected. The diagnostic evaluation was negative for 25 (71%) of the subjects who were evaluated. Among non-pregnant subjects ≥18 years of age, a review of symptoms and CD4 counts were available for 133. There were 46 subjects (35%) with CD4 cell counts < 100 and no neurological symptoms reported. No subjects underwent cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) screening and none received fluconazole to prevent CM.

Discussion

In this study, conducted in Senegal, West Africa, the majority of individuals presented with advanced HIV disease, defined as a CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3 or clinical stage 3 or 4, and therefore warranted care according to the WHO guidelines for the management of advanced HIV. The WHO guidelines recommend a package of care consisting of rapid initiation of ART, enhanced screening and diagnosis of TB and CM, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, IPT, fluconazole pre-emptive therapy, and adherence support [6, 9].

Provision of a package of care for people with advanced HIV disease is supported by data from two randomized trials of intervention packages for individuals with advanced disease in SSA [10, 11]. The first study, conducted among individuals with a CD4 cell count < 200 initiating ART in Tanzania and Zambia, evaluated a package consisting of CrAg screening with fluconazole pre-emptive therapy and adherence support compared to the standard of care. The intervention package resulted in a reduction in mortality from 18% in the standard of care group to 13% in the intervention group. The second study, conducted among individuals starting ART in Kenya, Uganda, Malawi, and Zimbabwe with CD4 counts < 100, evaluated an enhanced package consisting of co-trimoxazole, IPT, azithromycin, albendazole, and primary fluconazole prophylaxis without CrAg screening, compared to the standard of care (co-trimoxazole alone). Enhanced prophylaxis resulted in reduced death rates at 24 weeks compared to the standard of care (8.9% versus 12.2%; p = 0.03).

According to the WHO guidelines, “rapid initiation of ART should be offered to all PLHIV following a confirmed diagnosis and clinical assessment” with the exception of individuals suspected of having TB or CM [6]. Rapid initiation is defined as within 7 days from the day of HIV diagnosis, and should be prioritized among those with advanced disease. In our study, rapid initiation of ART occurred in only 34% of eligible subjects and 38% of those with advanced disease. When ART was initiated, the majority received WHO recommended first-line agents [9]. Contraindicated or sub-optimal regimens were given to 4 subjects, including the provision of efavirenz to a subject infected with HIV-2, treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir in an HIV-2 infected subject receiving treatment for TB, and treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir to two non-pregnant adults infected with HIV-1. Approximately 20% of HIV-infections in Senegal are due to HIV-2, which is intrinsically resistant to NNRTIs, including efavirenz. Protease inhibitors are part of first line treatment for HIV-2 and dually infected subjects in Senegal; individuals who are infected with HIV-2 and receiving treatment for TB receive triple NRTI therapy. Although integrase inhibitors are included as first line options in the 2016 WHO guidelines, they are currently not accessible in most settings in Senegal.

Rapid initiation of ART has the potential to improve ART uptake, retention in care and viral suppression, and to decrease disease progression, HIV transmission, and mortality [6, 12,13,14]. Barriers to early initiation of ART that have been reported in other regions of SSA include systems-based factors, such as requirements for pre-ART counseling sessions and multiple visits for laboratory testing, insufficient healthcare worker knowledge about HIV care, and ART stock-outs [6, 13, 15,16,17]. Among pregnant women in Kenya and Malawi, patient reported barriers include the need to seek approval from their husbands, and insufficient time to disclose their status with consequent potential for stigma, conflict, and domestic violence [18, 19]. Barriers to rapid initiation of ART in Senegal have not been reported, and it is possible that these factors differ depending on the setting. Site specific evaluations to identify systems-based and patient-based barriers and facilitators to rapid initiation of first line ART are warranted.

Notably, we did not find an association between advanced disease and clinic site, residence, education, number of children, marital status, employment, or food insecurity. The strongest predictors of advanced disease were age ≥ 35 years and having sought care from a traditional healer. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report an association between seeking care from a traditional healer and presentation with WHO defined advanced disease in SSA. Given the widespread use of traditional healers in SSA [20, 21], this finding may have important implications for HIV programs. Future studies to further explore this finding are indicated.

The WHO criteria for co-trimoxazole prophylaxis among PLHIV are CD4 count ≤350 cells/mm3 or clinical stage 3 or 4, or lifelong co-trimoxazole for any CD4 count in settings with a high prevalence of malaria or bacterial infections. An area of high malaria transmission is defined as > 1 case/1000 population per year [22]. Malaria is endemic in Senegal and 99% of the population is considered at high risk of infection [23]. The risk is especially high in the Casamance region where there were up to 200 confirmed cases per 1000 population in 2016. Based on these indicators, all PLHIV in Senegal should receive lifelong co-trimoxazole. Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis has been shown to reduce mortality in PLHIV by up to 45% and is well-established as an integral component of HIV care [24,25,26,27,28]. Nearly half of the individuals in this study did not receive co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, including one third of those with advanced disease. There is a critical need to identify barriers to the implementation of this intervention, which costs just a few cents day per day and is known to substantially decrease morbidity and mortality among PLHIV [24].

Tuberculosis remains the leading cause of death among PLHIV, responsible for one third of deaths among PLHIV globally [29, 30]. Strategies to reduce TB-associated mortality among PLHIV include increased TB case finding, IPT, and infection control. According to WHO guidelines, routine TB symptom screening using an algorithm containing fever, cough, weight loss and night sweats, should be used to help identify HIV-infected individuals who should undergo expedited diagnostic evaluation for TB, and those who should receive IPT. Furthermore, diagnostic evaluation with sputum Xpert MTB/RIF, rather than traditional microscopy, should be used as the initial test among symptomatic PLHIV. The lateral flow urine lipoarabinomannan assay (LF-LAM) may be used among symptomatic individuals with a CD4 count ≤100 or those who are severely ill [6, 9]. Among those who do not have any of the screening symptoms, active TB is considered unlikely and IPT should be offered.

Approximately half of the subjects in this study reported symptoms consistent with TB. Among those who were symptomatic, only 39% underwent diagnostic evaluation and for the majority, traditional microscopy was utilized. These findings indicate a need to identify barriers to diagnostic evaluation and to improve access to WHO recommended diagnostic tests. Importantly, among those who did not have TB symptoms, only one individual was provided with isoniazid (INH). That individual received a 2 week prescription for INH, although the WHO recommends a minimum of 6 months of IPT. The provision of IPT is recommended by the Senegal National AIDS program. Although the reasons for poor IPT uptake in Senegal have not been evaluated, barriers may include provider fear of undiagnosed TB, concerns about drug interactions, adverse effects, or medication adherence, uncertainty about eligibility criteria, or lack of awareness of national and international policies. A survey of physicians and healthcare workers involved in the care of PLHIV in Senegal could serve to elucidate these factors.

Cryptococcal meningitis (CM) is a leading cause of death among individuals with advanced HIV, accounting for 15–20% of global AIDS-related deaths [6, 31]. CrAg screening combined with pre-emptive anti-fungal therapy (PET) with fluconazole has the potential to reduce CM associated mortality [10, 32,33,34,35,36]. The WHO recommended package of care for individuals with advanced disease includes CrAg screening for individuals with a CD4 count < 100 followed by fluconazole for CrAg positive people without evidence of meningitis. The 2018 WHO guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of cryptococcal disease recommend that CrAg screening be performed for all HIV-positive adults with a CD4 count < 100 cells/mm3 and that screening should be considered at a CD4 count threshold of < 200 cells/mm3 [31]. When CrAg screening is not available, the recent guidelines state that fluconazole primary prophylaxis should be given to adults and adolescents living with HIV who have a CD4 cell count < 100 cells/mm3 (strong recommendation; moderate-certainty evidence) and may be considered at a higher CD4 cell count threshold of < 200 cells/mm3 (conditional recommendation; moderate-certainty evidence). Neither CrAg screening combined with PET nor fluconazole prophylaxis were provided to any of the subjects evaluated in our study. CrAg screening is not routinely available in Senegal and the recommendation for prophylaxis in the absence of screening was only recently released. If implemented, these strategies could provide important opportunities to decrease morbidity and mortality due to CM among PLHIV in Senegal.

The primary limitation of our study is sample size. Turnover of healthcare personnel and regional strikes involving healthcare personnel limited our ability to enroll all individuals who initiated ART during the study period. This was not a population-based study and may not be representative of PLHIV or those presenting for care overall in Dakar or Ziguinchor or more broadly in Senegal. Our study is further limited by incomplete data; completion of standardized national forms for the evaluation and management of HIV was inconsistent. A strength of our study is that we sequentially enrolled HIV-positive individuals initiating ART at two study sites in Senegal to capture a sample that is representative of the HIV-positive population and provide an evaluation of the management of advanced HIV disease that represents national practices.

Senegal was an early leader in responding to the HIV epidemic through the implementation of the first government ART treatment program in Africa in 1998. In the current era, proactive efforts to ensure adherence to WHO and Senegalese guidelines and access to evidence-based interventions for individuals with advanced HIV disease are similarly warranted.

Conclusion

We evaluated the implementation of the WHO guidelines for the management of advanced HIV disease among individuals initiating ART in Senegal, West Africa. We found that although the majority of individuals presented with advanced disease and warranted management according to WHO guidelines, there were numerous missed opportunities to prevent HIV-associated morbidity and mortality. Programmatic evaluation is needed to identify barriers to implementation and enhanced funding for operational research is indicated.

Abbreviations

- 3TC:

-

Lamivudine

- ABC:

-

Abacavir

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- CM:

-

Cryptococcal meningitis

- CNERS:

-

Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé

- CrAg:

-

Cryptococcal antigen

- EFV:

-

Efavirenz

- FTC:

-

Emtricitabine

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- INH:

-

Isoniazid

- IPT:

-

Isoniazid Preventive Therapy

- ISAARV:

-

Initiative Sénégalaise d’Accès aux ARV

- NNRTI:

-

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- NRTI:

-

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- PET:

-

Pre-emptive anti-fungal therapy

- PLHIV:

-

People Living with HIV

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- TDF:

-

Tenofovir

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data 2018. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 90–90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014 Available at: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

The IeDea and COHERE Cohort Collaborations. Global Trends in CD4 Cell Count at the Start of Antiretroviral Therapy: Collaborative Study of Treatment Programs. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(6):893–903 PubMed PMID: 29373672. PMCID: PMC5848308.

Carmona S, Bor J, Nattey C, Maughan-Brown B, Maskew M, Fox MP, et al. Persistent High Burden of Advanced HIV Disease Among Patients Seeking Care in South Africa's National HIV Program: Data From a Nationwide Laboratory Cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(suppl_2):S111–S7 PubMed PMID: 29514238. PMCID: PMC5850436.

Lahuerta M, Wu Y, Hoffman S, Elul B, Kulkarni SG, Remien RH, et al. Advanced HIV disease at entry into HIV care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy during 2006–2011: findings from four sub-saharan African countries. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):432–41 PubMed PMID: 24198226. PMCID: PMC3890338.

World Health Organization 2017. Guidelines for managing advanced HIV disease and rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy, July 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization. p. 2017. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/advanced-HIV-disease/en/. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household food insecurity access scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide (v. 3). Washington, D.C: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development; 2007.

World Health Organization 2007. WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIVstaging150307.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd ed; 2016.

Mfinanga S, Chanda D, Kivuyo SL, Guinness L, Bottomley C, Simms V, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis screening and community-based early adherence support in people with advanced HIV infection starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9983):2173–82 PubMed PMID: 25765698.

Hakim J, Musiime V, Szubert AJ, Mallewa J, Siika A, Agutu C, et al. Enhanced prophylaxis plus antiretroviral therapy for advanced HIV infection in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(3):233–45 PubMed PMID: 28723333.

Zolopa A, Andersen J, Powderly W, Sanchez A, Sanne I, Suckow C, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: a multicenter randomized strategy trial. PloS One. 2009;4(5):e5575 PubMed PMID: 19440326. PMCID: PMC2680972.

Amanyire G, Semitala FC, Namusobya J, Katuramu R, Kampiire L, Wallenta J, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention to streamline initiation of antiretroviral therapy in Africa: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(11):e539–e48 PubMed PMID: 27658873. PMCID: PMC5408866.

Rosen S, Maskew M, Fox MP, Nyoni C, Mongwenyana C, Malete G, et al. Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV at a Patient’s First Clinic Visit: The RapIT Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002015 PubMed PMID: 27163694. PMCID: PMC4862681.

Siedner MJ, Lankowski A, Haberer JE, Kembabazi A, Emenyonu N, Tsai AC, et al. Rethinking the “pre” in pre-therapy counseling: no benefit of additional visits prior to therapy on adherence or viremia in Ugandans initiating ARVs. PloS One. 2012;7(6):e39894 PubMed PMID: 22761924. PMCID: PMC3383698.

Semitala FC, Camlin CS, Wallenta J, Kampiire L, Katuramu R, Amanyire G, et al. Understanding uptake of an intervention to accelerate antiretroviral therapy initiation in Uganda via qualitative inquiry. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2017. 20:4 PubMed PMID: 29206357. PMCID: PMC5810312.

Muhamadi L, Nsabagasani X, Tumwesigye MN, Wabwire-Mangen F, Ekstrom AM, Peterson S, et al. Inadequate pre-antiretroviral care, stock-out of antiretroviral drugs and stigma: policy challenges/bottlenecks to the new WHO recommendations for earlier initiation of antiretroviral therapy (CD<350 cells/microL) in eastern Uganda. Health Policy. 2010;97(2–3):187–94 PubMed PMID: 20615573.

Katirayi L, Namadingo H, Phiri M, Bobrow EA, Ahimbisibwe A, Berhan AY, et al. HIV-positive pregnant and postpartum women’s perspectives about Option B+ in Malawi: a qualitative study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20919 PubMed PMID: 27312984. PMCID: PMC4911420.

Helova A, Akama E, Bukusi EA, Musoke P, Nalwa WZ, Odeny TA, et al. Health facility challenges to the provision of Option B+ in western Kenya: a qualitative study. Health policy and planning. 2017;32(2):283–91 PubMed PMID: 28207061. PMCID: PMC5886182.

UNAIDS. Collaborating with traditional healers for HIV prevention and care in sub-Saharan Africa: practical guidelines for programmes. UNAIDS best practice collection “UNAIDS/06.28E”. 2006. Available at: http://www.data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub07/jc967-tradhealers_en.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

World Health Organization 2010. African Health Observatory. Paulo Peter Mhame, Kofi Busia, Ossy MJ Kasilo. Clinical practices of African traditional medicine. African Health Monitor:13. Available at: http://www.aho.afro.who.int/en/ahm/issue/13/reports/clinical-practices-african-traditional-medicine. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

World Health Organization 2010. Methods for preparing the country profiles. Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2010/wmr2010_methods.pdf. Accessed 2.20.19.

World Health Organization. Malaria Country Profiles. 2016 Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/country-profiles/en/. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

World Health Organization 2006. Guidelines on Co-Trimoxazole Prophylaxis for HIV-Related Infections Among Children, Adolescents and Adults. 2006. Available at: http://www.who.int/entity/hiv/pub/guidelines/ctxguidelines.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

Suthar AB, Vitoria MA, Nagata JM, Anglaret X, Mbori-Ngacha D, Sued O, et al. Co-trimoxazole prophylaxis in adults, including pregnant women, with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(4):e137–50 PubMed PMID: 26424674.

Mermin J, Lule J, Ekwaru JP, Malamba S, Downing R, Ransom R, et al. Effect of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis on morbidity, mortality, CD4-cell count, and viral load in HIV infection in rural Uganda. Lancet. 2004;364(9443):1428–34 PubMed PMID: 15488218.

Wiktor SZ, Sassan-Morokro M, Grant AD, Abouya L, Karon JM, Maurice C, et al. Efficacy of trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole prophylaxis to decrease morbidity and mortality in HIV-1-infected patients with tuberculosis in Abidjan, cote d’Ivoire: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;353(9163):1469–75 PubMed PMID: 10232312.

Anglaret X, Chene G, Attia A, Toure S, Lafont S, Combe P, et al. Early chemoprophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole for HIV-1-infected adults in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire: a randomised trial. Cotrimo-CI Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353(9163):1463–8 PubMed PMID: 10232311.

Ford N, Shubber Z, Meintjes G, Grinsztejn B, Eholie S, Mills EJ, et al. Causes of hospital admission among people living with HIV worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(10):e438–44 PubMed PMID: 26423651.

UNAIDS. Fact sheet - Latest statistics on the status of the AIDS epidemic. 2017. Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

WHO Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention, and management of cryptococcal disease in HIV-infected adults, adolescents and children, March 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/cryptococcal-disease/en/. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

Meya DB, Manabe YC, Castelnuovo B, Cook BA, Elbireer AM, Kambugu A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of serum cryptococcal antigen screening to prevent deaths among HIV-infected persons with a CD4+ cell count < or = 100 cells/microL who start HIV therapy in resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(4):448–55 PubMed PMID: 20597693. PMCID: PMC2946373.

Kaplan JE, Vallabhaneni S, Smith RM, Chideya-Chihota S, Chehab J, Park B. Cryptococcal antigen screening and early antifungal treatment to prevent cryptococcal meningitis: a review of the literature. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(Suppl 3):S331–9 PubMed PMID: 25768872.

Rajasingham R, Meya DB, Boulware DR. Integrating cryptococcal antigen screening and pre-emptive treatment into routine HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(5):e85–91 PubMed PMID: 22410867. PMCID: PMC3311156.

Jarvis JN, Harrison TS, Lawn SD, Meintjes G, Wood R, Cleary S. Cost effectiveness of cryptococcal antigen screening as a strategy to prevent HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis in South Africa. PloS One. 2013;8(7):e69288 PubMed PMID: 23894442. PMCID: PMC3716603.

Jarvis JN, Govender N, Chiller T, Park BJ, Longley N, Meintjes G, et al. Cryptococcal antigen screening and preemptive therapy in patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: a proposed algorithm for clinical implementation. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic). 2012;11(6):374–9 PubMed PMID: 23015379.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study participants and the staff of the Services des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales, the Centre Régional de Recherche et de Formation à la Prise en Charge Clinique de Fann, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Fann and the Centre de Santé de Ziguinchor. Members of the University of Washington-Senegal Research Collaboration can be found at: http://www.uwsenegalresearch.com.

Funding

This study was supported by grants NIH-NIAID K23 AI120761 to N.A.B. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study may be made available in part from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have approved this manuscript. NAB, JFS, SN, ITT, DF, MBD, JPD, KF, IS and FS performed the research. JJM, NMM, CTN and MS contributed essential resources. NAB, SEH, and GSG designed the research study. NAB and SEH analysed the data. NAB, SEH and GSG wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study procedures were approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and the Senegal Comité National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Santé (CNERS). Written informed consent was required for participation in this study. For subjects < 18 years of age, consent to participate was obtained from their legal guardian.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

GSG has received research grants and support from the US National Institutes of Health, University of Washington, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Gilead Sciences, Alere Technologies, Merck & Co, Inc, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Cerus Corporation, ViiV Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Abbott Molecular Diagnostics. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Benzekri, N.A., Sambou, J.F., Ndong, S. et al. Prevalence, predictors, and management of advanced HIV disease among individuals initiating ART in Senegal, West Africa. BMC Infect Dis 19, 261 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3826-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3826-5