Abstract

Background

Vitamin D levels are associated with the extent of mycobactericidal activity. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-32 play roles in the vitamin D-mediated tuberculosis (TB) defense mechanism. Vitamin D induces IL-1β, which plays an important role in terms of resistance to TB. We evaluated whether the levels of vitamin D-related cytokines distinguished between those with active TB and latent TB infection (LTBI).

Methods

In total, 50 TB-infected patients (25 with active TB and 25 with LTBI following a TB outbreak in a high school) were enrolled. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D), IL-15, IL-32, and IL-1β levels were measured via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigen-induced and unstimulated cytokine levels were measured in the supernatants of the QuantiFERON TB Gold-In-Tube (QFT-GIT) assay.

Results

Plasma 25(OH)D and plasma IL-15 levels were lower in patients with active TB than in LTBI subjects (25(OH)D: 16.64 ng/mL vs. 21.6 ng/mL, P = 0.031; IL-15: 148.9 pg/mL vs. 189.8 pg/mL, P = 0.013). Plasma 25(OH)D levels correlated with the plasma levels of IL-15 and IL-1β in TB-infected patients. In addition, the plasma 25(OH)D levels correlated positively with the level of unstimulated IL-15 (IL-15nil) and negatively with that of TB antigen-stimulated IL-32 (IL-32TB) in QFT-GIT supernatants. Although the IL-15nil and IL-15TB levels were higher in LTBI subjects than patients with active TB, the IL-32nil and IL-32TB levels were higher in the latter patients. A combination of the IL-15nil and IL-32TB levels accurately predicted 91.3% of active TB patients and latent subjects, with an area under the curve of 0.964.

Conclusions

Our preliminary data showed that the levels of the vitamin D-related cytokines IL-15 and IL-32 differed between active TB patients and LTBI subjects. This result might be used as a basic data for developing biomarkers distinguishing between active TB and LTBI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent, ranking above Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), causing an estimated 1.3 million deaths annually in HIV-negative subjects [1]. New diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines are required. Vitamin D plays an immunomodulatory role in several autoimmune diseases, altering T cell responses and protecting the epithelial mucosal barrier against inflammation [2, 3]. Similarly, vitamin D protects against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by modulating immune responses, stimulating the production of antimicrobial peptides such as cathelicidin and promoting autophagy [4,5,6,7]. Vitamin D regulates the production of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-17, and IL-10 in patients with congestive heart failure and inflammatory bowel disease [2, 8]. Several studies have evaluated the clinical utilities of the levels of TB antigen-stimulated serum cytokines in terms of differentiating active from latent TB [9,10,11]. However, few studies have explored the levels of vitamin D-related cytokines both in serum and in the supernatants of the QuantiFERON TB Gold-in-Tube (QFT-GIT) test for TB.

IL-15 plays a protective role against M.tuberculosis and is used as an adjuvant during vaccination against various diseases [12,13,14]. Krutzik et al. found that IL-15 mediated a vitamin D-dependent antimicrobial pathway [15]. IL-32 augments immunity to M. tuberculosis by increasing the expression levels of the vitamin D receptor and antimicrobial peptides, as well as caspase-mediated apoptosis or autophagy [16, 17]. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 significantly increased the levels of IL-1β associated with resistance to TB [18]. Here, we explored the associations between the levels of vitamin D and several cytokines in sera and QTF-GIT supernatants, and whether these levels distinguished those with active and latent TB infections (LTBI).

Methods

Study population

In 2017, a TB outbreak occurred in a high school of Chuncheon city in South Korea. The first patient diagnosed with TB in April 2017 and two additional cases were identified in September 2017. The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention established 1st National TB control Plan (2013–2017) based on Public-Private Mix (PPM) TB control project and TB contact surveillance through TB patient monitoring and epidemiologic investigation [19]. It detected additional TB patients through TB contact investigation and provided checkups and treatment to latent TB infection.

An epidemiological investigation involving all students and staff was then performed in line with the national LTBI treatment policy [20]. The interferon gamma-release assay (IGRA) was performed with the aid of the QFT-GIT, and chest X-rays were taken. The QFT-GIT results were scored as negative, indeterminate, or positive (cutoff 0.35 IU/mL), as recommended by the manufacturer. A total of 106 subjects yielding positive results on the QFT-GIT test or with abnormal chest X-rays were transferred to Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital or Kangwon National University Hospital.

High-resolution chest tomography (HRCT) was performed on all subjects; HRCT distinguishes active TB from LTBI [21]. Those positive on the QFT-GIT test and lacking active TB lesions on HRCT were diagnosed with LTBI. Active TB was diagnosed if sputum specimens were culture-positive for M. tuberculosis or if the clinical TB criteria were met [22]. These included typical cavities and branching centrilobular nodules evident on HRCT, and good clinical and radiographic responses to anti-TB treatment.

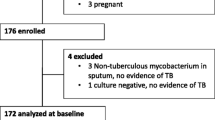

We commenced anti-TB medication for active TB patients; LTBI subjects were treated as dictated by the national TB control plan. In total, 28 TB patients and 70 LTBI subjects were diagnosed. Finally, 25 patients with active TB and 25 LTBI subjects gave written informed consent for inclusion in the present study. The consent of the parents was obtained because the age of participants was under 19 years old (Fig. 1).

Specimen collection and QFT-GIT assay

Blood samples were voluntarily given at enrolment, before therapy with anti-tuberculous drugs. The QFT-GIT assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany); we evaluated both active TB patients and LTBI subjects. After incubation for 20 h at 30 °C with M. tuberculosis-specific antigens (ESAT-6, CFP-10, and TB 7.7), plasma supernatants were collected after centrifugation and stored at − 80 °C prior to the assay.

Measurement of vitamin D and cytokine levels by ELISA

Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels [25(OH) D levels] were measured with the aid of a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Mybiosource, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The plasma levels of IL-15, IL-32, and IL-1β in all patients were measured using commercial ELISA kits according to the manufacturers’ instructions (IL-15: Raybiotech, Norcross, GA, USA, Catalog # ELH-IL15; IL-32: Mybiosource, Catalog # MBS720152; and IL-1β: Cusabio, Houston, TX, USA, Catalog # CSB-E08053h); the levels of these materials in QFT-GIT supernatants from the QuantiFERON nil and antigen tubes were also measured.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs); we performed nonparametric analysis. Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test or the Mann–Whitney U-test. Correlations between vitamin D and cytokine levels were sought using Spearman’s rank test. The most appropriate cutoff values for vitamin D and cytokine levels were derived by reference to the maximal Youden indices of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the probability of active TB in each patient based on an equation featuring independent factors. Statistical analysis was performed with the aid of GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (v. 20; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study participants

We enrolled 25 patients with active pulmonary TB and 25 LTBI subjects. The demographic characteristics of all participants are shown in Table 1. The age and gender distributions of the active TB and LTBI groups did not differ. Two patients in the active TB group yielded negative IGRA results, and 15 patients in that group were acid-fast bacillus (AFB) culture-negative. As TB was diagnosed soon after contact, lung involvement was limited to one lobe in most cases.

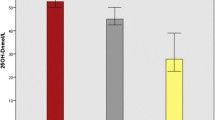

Levels of plasma cytokines, and M. Tuberculosis antigen-induced and unstimulated cytokines

As shown in Fig. 2, the 25(OH)D level differed between those with active TB (median 16.64 IU/mL, IQR: 13.32–36.81) and latent TB (median 21.60 IU/mL, IQR: 13.32–36.81 IU/mL, P = 0.033). The plasma IL-15 was significantly lower in patients with active TB (median 148.9 pg/mL, IQR 120.6–184.8 pg/mL) than LTBI subjects (median 189.8 pg/mL, IQR 174.2–225.7 pg/mL). However, the plasma IL-32 levels and plasma IL-1β level did not differ between active TB and LTBI subjects.

Figure 3 shows the IL-15, IL-32, and IL-1β levels following antigen stimulation during the QFT-GIT test in the active TB and LTBI groups. The median levels of unstimulated IL-15 (IL-15nil) and the IL-15 response to TB antigens (IL-15TB) were significantly lower in those with active TB than the LTBI group (IL-15nil: active TB 94.62 pg/mL, IQR 79.08–109.6 pg/mL; LTBI 162.8 pg/mL, IQR 146.1–222.6 pg/mL, P < 0.001; IL-15TB: active TB 152.2 pg/mL, IQR 114.7–234.6 pg/mL, LTBI 210.4 pg/mL, IQR 177.4–272.4 pg/mL, P = 0.025). On the contrary, the medians of the unstimulated IL-32 (IL-32nil) and IL-32 responses to TB antigen (IL-32TB) were significantly higher in the active TB than the LTBI group (IL-32nil: active TB 1925 pg/mL, IQR 766.5–2927 pg/mL; LTBI 410.2 pg/mL, IQR 306.7–842.9 pg/mL, P < 0.001; IL-32TB: active TB 992.8 pg/mL, IQR 741.4–2132 pg/mL; LTBI 405.2 pg/mL, IQR 361.3–552.0 pg/mL, P < 0.001). Neither the unstimulated IL-1β level nor the IL-1β response to TB antigen differed between the active TB and LTBI groups.

Correlation between cytokine and vitamin D levels

In TB-infected patients (25 active TB and 25 LTBI), the 25(OH)D level correlated positively with those of plasma IL-15 (r = 0.390, P = 0.007) and plasma IL-1β (r = 0.382, P = 0.013) (Fig. 4). In terms of the QFT-GIT test data, 25(OH)D levels correlated positively with the IL-15nil (r = 0.355, P = 0.018) and negatively with the IL-32TB (r = − 0.314, P = 0.038) and IL-32TB–nil (r = − 0.418, P = 0.005) values (Fig. 5). We found no significant correlation between the plasma concentrations of cytokines. Significant correlations were evident between the IL-15nil value and those of other cytokines measured in QFT-GIT supernatants. The IL-15nil value correlated negatively with the IL-32nil (r = − 0.314, P = 0.038), IL-32TB (r = − 0.314, P = 0.038), and IL-1βnil (r = − 0.314, P = 0.038) values.

Capacity of vitamin D/cytokine levels to discriminate between active and latent TB

To evaluate the use of vitamin D-related cytokine levels for the diagnosis of active TB and LTBI, we performed ROC analysis of several markers in plasma and supernatants of the QFT test (Table 2). IL-15nil exhibited the highest area under the curve (AUC) (0.951), followed by IL-32TB (0.941), IL-32nil (0.811), and plasma IL-15 (0.777). At a cut-off of 167.6 pg/mL, plasma IL-15 afforded 65.2% sensitivity and 82.6% specificity, whereas IL-15nil, at a cut-off of 137.2 pg/mL, afforded a sensitivity and specificity of 90.9 and 88% respectively. At a cut-off of 174.2 pg/mL, IL-15TB afforded 63.6% sensitivity and 80.0% specificity. IL-32nil afforded 86.4% sensitivity and 76% specificity at a cut-off of 662.3 pg/mL and IL-32TB 90.9% sensitivity and 92.0% specificity at a cut-off of 627.6 pg/mL. We used multivariate logistic regression to analyze the cytokines exhibiting the highest AUCs (IL-15nil and IL-32TB). Both were independent predictors of active TB, as revealed by the equation:

Logit (probability) = Ln (probability/1 – probability) = [3.357 × (IL-15nil < 137.2 pg/mL)] + [3.890 × (IL-32TB ≥ 627.6 pg/mL)] – 3.785.

ROC analysis showed that the predicted probability had an AUC of 0.964 at an optimal cut-off of 0.208 (100% sensitivity and 82.6% specificity). Active TB was favored if one of two criteria (IL-15nil < 137.2 pg/mL or IL-32 TB ≥ 627.6 pg/mL) was met. This two-factor model afforded increased sensitivity at the cost of mildly reduced specificity compared to models involving other biomarkers. There was no false-negative patient in the active TB group but three false-positive patients in the LTBI group. Notably, in two patients, active TB was correctly diagnosed based on both criteria, although the initial IGRA results were negative.

Discussion

Several studies have described associations between TB and vitamin D deficiency [23,24,25,26]. One epidemiological study found that Korean TB patients exhibited a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency than healthy subjects [23]. Arnedo-Pena et al. found that vitamin D concentration correlated with a low incidence of conversion after TB infection [27]. Similarly, Balcells et al. found that the most important determinant of vitamin D deficiency was seasonality and LTBI acquisition risk was higher in spring compared with other season of the year [28]. Our results are consistent with those of a Spanish study demonstrating that a severe deficit of vitamin D (< 10 ng/mL) could be used to distinguish active TB from LTBI [29].

Several in vitro studies found associations between vitamin D levels and antimicrobial cytokine release. IL-15 mediates TLR2/1-induced induction of the CYP27b1, VDR, and cathelicidin as vitamin D-dependent pathways involved in macrophage differentiation [15]. Montaya et al. found that IL-32 induced vitamin D-dependent antimicrobial peptides during the IL-15-mediated defense response of the macrophage gene network [17]. Vitamin D triggered IL-1β secretion in macrophages of TB patients, effectively restricting bacterial growth [18]. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-induced IL-1β secretion from macrophages, and reduced the mycobacterial burden by modulating paracrine signaling [30].

We showed that there is a significant difference in vitamin D-related cytokines between active TB patients and latent TB subjects. The plasma IL-15 and IL-15nil levels correlated positively with the vitamin D level. The plasma IL-15 levels and IL-15nil and IL-15TB levels were significantly higher in those with LTBI than active TB, but the TB-specific antigen-dependent IL-15 level (IL-15TB–nil) was not. This result is similar to that of Chandrashekara et al., who found that the serum IL-15 level was significantly lower in a TB-infected group than healthy controls [31]. IL-15 boosts the immune response to infection by activating NK cells and enhancing priming of CD4/CD8 cells in terms of IFN–r production in patients with TB [32, 33]. Frahm et al. reported that the IL-15TB–nil level was significantly higher in those with active than latent TB [34]. This differs from our finding, perhaps because the cited study included those with HIV infections and patients who had completed TB treatment at the time of enrolment.

The plasma IL-32 level did not distinguish active from latent TB and did not correlate with the vitamin D level, but the IL-32TB level was significantly higher in those with active than latent TB, and correlated negatively with the vitamin D level in the present study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to measure IL-32 levels in QFT-GIT supernatants.

Previous studies yielded inconsistent results. Bao et al. reported that the serum IL-32 level of a TB group was significantly higher than that of a control group [35] and later reported that lung IL-32 expression was increased in patients with active TB [36]. On the contrary, Montaya reported that the IL-32 mRNA level in peripheral blood was lowest in those with active TB, compared to those with latent TB and healthy controls [17]. Both IL-15 and IL-32 protect against TB [13, 37]. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis revealed that IL-32 was linked to IL-15 in terms of induction of the defense response network [17]. However, in our present in vivo study, we found differences in the expression levels of the two cytokines in those with active TB and LTBI subjects. The reason may be that IL-32 production could be affected by other signal pathways such as IL-18 and caspase-1. Further research is needed to conclude the role of IL-32 according to the spectrum of TB infection.

We found that the plasma IL-1β level correlated positively with the vitamin D level but did not distinguish active TB from LTBI. Wergeland et al. showed that the IL-1β level of unstimulated (“nil”) supernatants was lower in an active TB than an LTBI group [38], but we found that IL-1β levels in QFT-GIT supernatants did not differ between the active TB and LTBI groups.

We chose optimal cytokine cutoff levels distinguishing active TB from LTBI. We performed logistic regression by reference to vitamin D and vitamin D-related cytokine levels. On multivariate logistic regression, an IL-15nil level < 137.2 pg/mL and IL-32TB level ≥ 627.6 pg/mL independently predicted active TB. When the probability predicted by the regression model was ≥0.208 (100% sensitivity and 82.6% specificity), active TB was favored when QFT-GIT analysis fulfilled one of above two criteria (IL-15nil and IL-32TB). The predictive factor model combining IL-15nil and IL-32TB improved the sensitivity compared with each marker and continued high sensitivity.

Our study had several limitations. First, there is no gold standard test for latent TB infection, LTBI was defined by QFT-GIT to assess the immunologic reaction to specific antigens of M. tuberculosis in this study. Second, we lacked healthy controls of TB outbreak in a high school. Third, validation is needed in larger population because the sample size is small and potential for type I error exists. Because this study is done through TB contact investigation after TB outbreak, the additional subjects could not be recruited.

The strength of the study is that the LTBI and active TB groups were enrolled from a TB outbreak in a high school. Therefore, age, gender, and the TB exposure environment were near-identical in the two groups.

Conclusions

In summary, the levels of vitamin D, plasma IL-15, IL-15nil, and IL-32TB differentiated active TB from LTBI. The correlations between vitamin D and cytokine levels suggest that certain cytokines mediate the TB-protective effects of vitamin D. Measurement of both IL-15nil and IL-32TB in QFT-GIT supernatants accurately discriminated active TB from LTBI. Further studies in more diverse populations are required to validate the utility of these markers.

Abbreviations

- 25(OH)D:

-

25-hydroxyvitamin D

- AFB:

-

acid-fast bacillus

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HRCT:

-

High-resolution chest tomography

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IQR:

-

interquartile ranges

- LTBI:

-

Latent tuberculosis infection

- QFT-GIT:

-

QuantiFERON TB Gold-In-Tube

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

References

GLOBAL. TUBERCULOSIS REPORT 2017. In. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017.

Gubatan J, Mitsuhashi S, Longhi MS, Zenlea T, Rosenberg L, Robson S, Moss AC. Higher serum vitamin D levels are associated with protective serum cytokine profiles in patients with ulcerative colitis. Cytokine. 2018;103:38–45.

Cantorna MT, Mahon BD. Mounting evidence for vitamin D as an environmental factor affecting autoimmune disease prevalence. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2004;229(11):1136–42.

Chocano-Bedoya P, Ronnenberg AG. Vitamin D and tuberculosis. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(5):289–93.

Ralph AP, Kelly PM, Anstey NM. L-arginine and vitamin D: novel adjunctive immunotherapies in tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16(7):336–44.

Gombart AF, Borregaard N, Koeffler HP. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. FASEB J. 2005;19(9):1067–77.

Shin DM, Yuk JM, Lee HM, Lee SH, Son JW, Harding CV, Kim JM, Modlin RL, Jo EK. Mycobacterial lipoprotein activates autophagy via TLR2/1/CD14 and a functional vitamin D receptor signalling. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12(11):1648–65.

Schleithoff SS, Zittermann A, Tenderich G, Berthold HK, Stehle P, Koerfer R. Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(4):754–9.

Hong JY, Jung GS, Kim H, Kim YM, Lee HJ, Cho SN, Kim SK, Chang J, Kang YA. Efficacy of inducible protein 10 as a biomarker for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2012;16(12):e855–9.

Chegou NN, Detjen AK, Thiart L, Walters E, Mandalakas AM, Hesseling AC, Walzl G. Utility of host markers detected in Quantiferon supernatants for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in children in a high-burden setting. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64226.

Won EJ, Choi JH, Cho YN, Jin HM, Kee HJ, Park YW, Kwon YS, Kee SJ. Biomarkers for discrimination between latent tuberculosis infection and active tuberculosis disease. J Inf Secur. 2017;74(3):281–93.

Patidar M, Yadav N, Dalai SK. Interleukin 15: a key cytokine for immunotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016;31:49–59.

Pydi SS, Bandaru AR, Venkatasubramanian S, Jonnalagada S, Valluri VL. Vaccine for tuberculosis: up-regulation of IL-15 by Ag85A and not by ESAT-6. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2011;91(2):136–9.

Rausch A, Hessmann M, Holscher A, Schreiber T, Bulfone-Paus S, Ehlers S, Holscher C. Interleukin-15 mediates protection against experimental tuberculosis: a role for NKG2D-dependent effector mechanisms of CD8+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(5):1156–67.

Krutzik SR, Hewison M, Liu PT, Robles JA, Stenger S, Adams JS, Modlin RL. IL-15 links TLR2/1-induced macrophage differentiation to the vitamin D-dependent antimicrobial pathway. J Immunol. 2008;181(10):7115–20.

Bai X, Dinarello CA, Chan ED. The role of interleukin-32 against tuberculosis. Cytokine. 2015;76(2):585–7.

Montoya D, Inkeles MS, Liu PT, Realegeno S, Teles RM, Vaidya P, Munoz MA, Schenk M, Swindell WR, Chun R, et al. IL-32 is a molecular marker of a host defense network in human tuberculosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(250):250ra114.

Eklund D, Persson HL, Larsson M, Welin A, Idh J, Paues J, Fransson SG, Stendahl O, Schon T, Lerm M. Vitamin D enhances IL-1beta secretion and restricts growth of mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages from TB patients. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2013;2(1):18–25.

Go U, Park M, Kim U-N, Lee S, Han S, Lee J, Yang J, Kim J, Park S, Kim Y. Tuberculosis prevention and care in Korea: evolution of policy and practice. J Clin Tubercul Mycobacter Dis. 2018.

Lee SW, Jang YS, Park CM, Kang HY, Koh WJ, Yim JJ, Jeon K. The role of chest CT scanning in TB outbreak investigation. Chest. 2010;137(5):1057–64.

Organization WH. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for National Programmes. 3rd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

Hong JY, Kim SY, Chung KS, Kim EY, Jung JY, Park MS, Kim YS, Kim SK, Chang J, Kang YA. Association between vitamin D deficiency and tuberculosis in a Korean population. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(1):73–8.

Joo MH, Han MA, Park SM, Shin HH. Vitamin D deficiency among adults with history of pulmonary tuberculosis in Korea based on a Nationwide survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(4).

Ho-Pham LT, Nguyen ND, Nguyen TT, Nguyen DH, Bui PK, Nguyen VN, Nguyen TV. Association between vitamin D insufficiency and tuberculosis in a Vietnamese population. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:306.

Wejse C, Olesen R, Rabna P, Kaestel P, Gustafson P, Aaby P, Andersen PL, Glerup H, Sodemann M. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in a west African population of tuberculosis patients and unmatched healthy controls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(5):1376–83.

Arnedo-Pena A, Juan-Cerdan JV, Romeu-Garcia MA, Garcia-Ferrer D, Holguin-Gomez R, Iborra-Millet J, Pardo-Serrano F. Vitamin D status and incidence of tuberculosis infection conversion in contacts of pulmonary tuberculosis patients: a prospective cohort study. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(8):1731–41.

Balcells ME, Garcia P, Tiznado C, Villarroel L, Scioscia N, Carvajal C, Zegna-Rata F, Hernandez M, Meza P, Gonzalez LF, et al. Association of vitamin D deficiency, season of the year, and latent tuberculosis infection among household contacts. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175400.

Esteve Palau E, Sanchez Martinez F, Knobel Freud H, Lopez Colomes JL, Diez Perez A. Tuberculosis: plasma levels of vitamin D and its relation with infection and disease. Med Clin (Barc). 2015;144(3):111–4.

Verway M, Bouttier M, Wang TT, Carrier M, Calderon M, An BS, Devemy E, McIntosh F, Divangahi M, Behr MA, et al. Vitamin D induces interleukin-1beta expression: paracrine macrophage epithelial signaling controls M. Tuberculosis infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(6):e1003407.

Chandrashekara S, Anupama KR, Sambarey A, Chandra N. High IL-6 and low IL-15 levels mark the presence of TB infection: a preliminary study. Cytokine. 2016;81:57–62.

Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin 15: biology and relevance to human disease. Blood. 2001;97(1):14–32.

Combe CL, Moretto MM, Schwartzman JD, Gigley JP, Bzik DJ, Khan IA. Lack of IL-15 results in the suboptimal priming of CD4+ T cell response against an intracellular parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(17):6635–40.

Frahm M, Goswami ND, Owzar K, Hecker E, Mosher A, Cadogan E, Nahid P, Ferrari G, Stout JE. Discriminating between latent and active tuberculosis with multiple biomarker responses. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2011;91(3):250–6.

Bao F, Wen X, Liu A, Dai X, Zhao Q, Wang Y. Lu S: elevated levels of serum IL-32 in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2012;6(45):7292–4.

Bai X, Shang S, Henao-Tamayo M, Basaraba RJ, Ovrutsky AR, Matsuda JL, Takeda K, Chan MM, Dakhama A, Kinney WH, et al. Human IL-32 expression protects mice against a hypervirulent strain of mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(16):5111–6.

Bai X, Kim SH, Azam T, McGibney MT, Huang H, Dinarello CA, Chan ED. IL-32 is a host protective cytokine against mycobacterium tuberculosis in differentiated THP-1 human macrophages. J Immunol. 2010;184(7):3830–40.

Wergeland I, Assmus J, Dyrhol-Riise AM. Cytokine patterns in tuberculosis infection; IL-1ra, IL-2 and IP-10 differentiate borderline QuantiFERON-TB samples from uninfected controls. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0163848.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hallym University Research Fund (grant no. HURF-2017-20); the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (grant no. NRF- 2017M3A9E8033225); a National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (grant no. NRF 2017R1C1B5017879); and a 2018 Research Grant from Kangwon National University. HURF-2017-20 and NRF- 2017M3A9E8033225 provided the necessary resources (ELISA kits and QFT-GIT assay) for collection of data. NRF 2017R1C1B5017879 and 2018 Research Grant from Kangwon National University provided professional staff suitable for the analysis and interpretation of data.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YH and JYH conceived the idea for this paper, YK1, JJL, YH and JYH conducted the analysis and wrote the manuscript. JJL, YK1, MGL, CYL, YK2 and JYH participated in project oversight. YH, JH, SSH, SJL and WJK participated in the design of the study. All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, Y., Kim, Y., Lee, J.J. et al. Levels of vitamin D-associated cytokines distinguish between active and latent tuberculosis following a tuberculosis outbreak. BMC Infect Dis 19, 151 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3798-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3798-5