Abstract

Background

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is known to cause urinary tract infection (UTI) and meningitis in neonates, as well as existing as a commensal flora of the human gut. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli has increased in the community with the spread of CTX-M type ESBL-producing sequence type 131 (ST131)-O25-H30Rx E. coli clone. The role of ESBL-producing E. coli in female genital tract infection has not been elucidated. The clinical and molecular features of E. coli isolated from community-onset female genital tract infections were evaluated to elucidate the current burden in the community, focusing on the highly virulent and multidrug-resistant ST131 clone.

Methods

We collected and sequenced 91 non-duplicated E. coli isolates from the female genital tract of 514 patients with community-onset vaginitis. ESBL genotypes were identified by PCR and confirmed to be ESBL-producers by sequencing methods. ST131 clones were screened by PCR for O16-ST131 and O25b-ST131. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) were conducted in ESBL producers. Independent clinical risk factors associated with acquiring ESBL-producing E. coli and ST131 clone were analyzed using multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

Of the 514 consecutive specimens obtained from the infected female genital tract, 17.7% (91/514) had E. coli infection, of which 19.8% (18/91) were ESBL producers. CTX-M-15 was the most common type (n = 15). O25b-ST131 and O16-ST131 clones accounted for 15.4% (14/91) and 6.6% (6/91), respectively. In plasmid analysis, ten isolates succeeded in conjugation and plasmid types were IncFII (n = 4), IncFI (n = 3), IncI1-Iγ (n = 3) with one non-typable case. Compared to ESBL-nonproducing E. coli, ESBL-producing E. coli acquisition was strongly associated with recurrent vaginitis (OR 40.130; 95% CI 9.980–161.366), UTI (OR 18.915; 95% CI 5.469–65.411), and antibiotics treatment (OR 68.390; 95% CI 14.870–314.531).

Conclusion

A dominant clone of CTX-M type ESBL-producing E. coli in conjugative plasmids seems to be circulating in the community and considerable number of ST131 E. coli in the genital tract of Korean women was noted. Sustained monitoring of molecular epidemiology and control of the high-risk group is needed to prevent ESBL-producing E. coli from spreading throughout the community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is known to cause urinary tract infection (UTI), surgical site infection, and meningitis in neonates, as well as existing as a commensal flora of the human gut [1, 2]. The colonization of E.coli has been reported in both pregnant (24–31%) and non-pregnant (9–28%) women [3, 4]. The clinical risk factors for E. coli colonization or infection in the female genital tract is not fully understood, but postmenopausal changes including cessation of estrogen production, increased vaginal pH, disappearance of lactobacilli with the concurrent colonization of Enterobacteriaceae including E. coli is thought to play a role.5 Pregnant women with E. coli infection prompt additional attention due to its consequences regarding the pregnancy outcome including the infection of the new born [5].

In the past decade, colonization or infection of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli has remarkably increased in the community, mostly due to the spread of high virulent and multidrug-resistant sequence type 131 (ST131) E. coli clone [6,7,8]. According to recent epidemiologic studies based on community-onset UTI, the situation of Korea is not different [6,7,8]. The presence of ESBL-producing E. coli in female genital tract infections are scarcely identified within our knowledge.

In this prospective observational study, risk factors and molecular features of female genital tract infections by E. coli were evaluated. We focused on the highly virulent and multidrug-resistant ST131 clone because it could be another indicator of the spread in the community and an emerging public health threat.

Methods

For the prospective observational study, 91 non-duplicated E. coli isolates from the female genital tract specimens of 514 consecutive, sequentially encountered patients were analyzed. All specimen were retrieved from one community hospital in Gyeonggi-do province, South Korea (742 beds) under the diagnosis of community-onset vaginitis or cervicitis between June 2016 and April 2017. All patients had infection signs such as increased leucorrhoea, vaginal dyspareunia, intermittent pruritus, burning sensation, and foul odor. Sites of the acquisition were determined as described by Friedman with some modifications [9]. Community-onset was defined as diagnosis given within 48 h of admission, further categorized as community-onset healthcare-associated (COHA) and community-associated (CA) group. COHA infections had any one of the following histories: attended a hospital or hemodialysis clinic or received intravenous chemotherapy in the 30 days before the infection; hospitalized in an acute care hospital for 2 or more days in the 90 days, transfer-in from other healthcare facility before the infection. Others were defined as CA infection [9].

Species Identification and susceptibility testing were performed with Microscan Walk-away plus system (BeckmanCoulter, Inc., CA, USA) and MicroScan Neg Breakpoint Combo Type 44 (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., West Sacramento, CA, USA). Antimicrobial susceptibility of the 91 E. coli isolates was tested and interpreted using CLSI criteria [10]. ESBL production was confirmed by ESBL double-disk synergy test [11], and ESBL genotype was determined by PCR and sequencing [12]. For the detection of ST131, all isolates were screened by PCR for O16-ST131, and O25b-ST131 [13]. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described in our previous study [14]. The patterns were analyzed using InfoQuest FP software (Bio-Rad) to generate a dendrogram based on the unweighted pair group method, with an arithmetic average (UPGMA) from the Dice coefficient with 1% band position tolerance and 0.5% optimization settings. A PCR based replicon typing (PBRT) were schemed in the 18 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates, targeting the replicons of the major plasmid families occurring in Enterobacteriaceae (HI2, HI1, I1-γ, X, L/M, N, FIA, FIB, FIC, W, Y, P, A/C, T, K, B/O) according to the protocol by Carattoli, et al. [15] Ten of the 18 isolates were successfully conjugated and PBRT was performed in these 10 transconjugants.

To find the independent clinical risk factors associated with acquiring the ESBL-producing E. coli and ST131 clone, medical records were reviewed for the patient’s age, pregnancy status, pregnancy outcome, menopause status, underlying medical conditions such as Diabetes Mellitus(DM) and hypertension, use of the intrauterine device or pessary, nursing home residency, pelvic inflammatory disease(PID), types of vaginitis such as atrophic vaginitis or chlamydial infection, previous antimicrobial treatment within 1 month, history of UTI within 1 month, and history of recurrent vaginitis within 1 month.

Statistical analysis was performed using Chi-square test for the comparative analysis of categorical variables to determine the independent risk factors. Fisher’s exact test was used when 25% of the cells had an expected frequency of less than 5. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) values were calculated for binomial variables. Variables were first compared using univariate logistic regression, then a multivariate analysis using a backward selection with variables with a p-value < 0.1 in the univariate study was carried out. Multivariate logistic regression model was adjusted for age, pregnancy, intrauterine device use, menopause, admission from the nursing home, PID, recurrent vaginitis, UTI and previous antibiotic treatment within one month. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and SAS 9.4(SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used.

Results

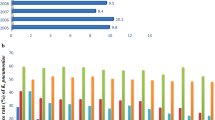

Of the 514 consecutive specimens obtained from the infected female genital tract, 17.7% (91/514) had E. coli infection, of which 19.8% (18/91) were ESBL producers. All ESBL-producers had the CTX-M genotypes; CTX-M-15 was the most common type (n = 15), one of which also had CTX-M-27. CTX-M-55 producers were also detected (n = 3). Of the total 19 E. coli isolates, O25b-ST131 accounted for 15.4% (14/91) and O16-ST131 clones for 6.6% (6/91). Seven of the 18 ESBL producers were a ST131 clone with four being O25b-ST131 and three O16-ST131 (Table 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). PFGE patterns of ESBL-producing E. coli showed three dominant clonal groups with the cut off 80% similarity, suggesting the clonal spread of ESBL-producing E. coli in the community (Fig. 1). In plasmid analysis, ten isolates succeeded in conjugation and plasmid types were IncFII (n = 4), IncFI (n = 3), IncI1-Iγ (n = 3) and one non-typable (Table 1). Antimicrobial susceptibility of the 91 E. coli isolates were analyzed. ST131 clone showed high resistance rates (RRs) to both 3rd generation cephalosporin and fluoroquinolones; 36% (O25b-ST131) versus 20% (non-ST131) to cefotaxime and 50% (O25b-ST131) versus 35% (non-ST131) to ciprofloxacin (Table 2 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

The median age of the patients with ESBL-producing E. coli was 45 years old (31–96) and accompanying diseases were recurrent vaginitis (n = 4), atrophic vaginitis (n = 3), pelvic inflammatory disease (n = 3), preterm labor (n = 3), and UTI (n = 2). They were treated with a variety of antimicrobial therapies, which included cephalosporin, carbapenems, piperacillin-tazobactam, and amikacin, alone or in combination and achieved a clinical cure. All three pregnancies with ESBL-producing E. coli female genital tract infection were prematurely terminated due to preterm labor (Table 1).

Independent clinical risk factors for acquiring the ESBL-producing E. coli over non-ESBL producing E. coli were preterm labor (OR, 10.911, 95% CI, 1.199–99.301; P = 0.0339), intrauterine device insertion (OR, 6.460; 95% CI, 1.004–41.568; P = 0.0495), history of recurrent vaginitis within one month (OR, 40.130; 95% CI, 9.980–161.366; P ≤ 0.0001), history of UTI within one month (OR, 18.915; 95% CI, 5.469–65.411; P ≤ 0.0001), and antibiotics treatment within one month (OR, 68.390; 95% CI, 14.870–314.531; P ≤ 0.0001) (Table 3) .

Clinical characteristics were compared between the ST131 and non-ST131 clone. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusting for the compounding variables, independent risk factors with statistical significance could not be found that were associated with acquiring the ST131 clone (Table 3).

Discussion

ESBL-producing E. coli was considered to be a crucial nosocomial pathogen when it was first isolated in the late 1980s [6,7,8]. With the occurrence of the ST131 clone, ESBL-producing E. coli in the community setting has been widely noted in recent studies [16,17,18]. Our previous study showed that 27% (58/213) of E. coli isolates from UTI patients belonged to the globally epidemic ST131 clone [6]. The Korean Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (KARMS) reported the resistance rates of E. coli to cefotaxime to be 35% in 2015 [19]. Asymptomatic carriage of ESBL-producing E. coli among healthy individuals playing the role of reservoir are also known to have increased [20]. Fecal colonization with ESBL-producing E. coli are also on the rise [21].

Analysis of vaginal microbiome showed region-specific variation, setting the basis of the need for a region-specific data of the epidemic multi-drug resistant ST131 ESBL-producing E. coli clone [22, 23]. We evaluated the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli, focusing on the ST131 clone in female genital tract infections because it could be another indicator of the spread of highly virulent and multi-drug resistant E. coli in the community, which could be an emerging threat to the public health.

Of the 514 consecutive specimens obtained from the infected female genital tract, 17.7% (91/514) had E. coli infection, of which 19.8% (18/91) were ESBL producers. Fourteen of the 18 ESBL producers were community-associated(CA) without any history of hospitalization, suggesting the possibility of community based spread of ESBL-producing E. coli (Table 1).

CTX-M-15 was the most common type (n = 15) and this was in accordance of the previous isolates of CTX types in Korea in which either CTX-M-1 group (including CTX-M-15 or CTX-M-55) or CTX-M-9 group (including CTX-M-14 or CTX-M-27) prevailed [6, 7]. CTX-M-55 genotype is a variant of CTX-M-15 with a single amino acid substitution, which was known to frequent in China and considered as a potential threat to community spread [24]. Recently CTX-M-55-producing Shigella and Salmonella were isolated in Korea with blaCTX-M-55 genes inserted into IncI1, IncA/C, and IncZ plasmid, downstream of ISEcp1, IS26-ISEcp1 and ISEcp-IS5 sequences, which suggests CTX-M-55 dissemination to different bacterial species by lateral plasmid transfer [25]. In this study, ten of 18 ESBL-producing E. coli succeeded in conjugation, and plasmid types were IncFII (n = 4), IncFI (n = 3), IncI1-Iγ (n = 3) with one non-typable case. Most of ESBL-producing E. coli showed similar clonality in PFGE, which suggests that dominant clone of CTX-M type ESBL-producing E. coli in conjugative plasmids are circulating in the community.

O25b-ST131 and O16-ST131 clones accounted for 15.4% (14/91) and 6.6% (6/91), respectively, suggesting a high prevalence of ST131 E. coli clone in the female genital tracts of Korean women. The expansion of the ST131 E. coli clone with phylogenetic B2, serotype O25b, fimH type H30 is suggested to reveal multidrug resistant property [8, 17]. In this study, O25b-ST131 clones showed high rates of multidrug-resistancy against the 3rd generation cephalosporins as well as fluoroquinolones (Table 2 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

Compared to the ESBL-nonproducing E. coli group, ESBL-producing E. coli group showed higher tendency of having clinical features such as history of recurrent vaginitis within 1 month (OR, 40.130; 95% CI, 9.980–161.366; P ≤ 0.0001), history of UTI within 1 month (OR, 18.915; 95% CI, 5.469–65.411; P ≤ 0.0001), and history or antibiotics treatment within 1 month (OR, 68.390; 95% CI, 14.870–314.531; P ≤ 0.0001). E. coli is a well-known etiologic agent for UTI, so it is not surprising that female genital tract infection with ESBL-producing E. coli were strongly associated with UTI [6,7,8]. Previous antibiotic exposure might have resulted in the selection pressure of a resistant clone, concomitantly developing multidrug-resistancy [14, 26].

Aerobic vaginitis is a recently defined vaginitis type, which differs from the common bacterial vaginosis in terms of scarce presence of lactobacilli and positive cultured aerobic bacteria including group B streptococci, E.coli, and enterococci [5]. In postmenopausal women with atrophic vaginitis, the lack of estrogen results in deficiency of mucosal epithelial barrier, lactobacilli disappear from the vaginal flora decreasing the pH of the vagina, resulting in predominant colonization by Enterobacteriaceae, especially E. coli., serving an adequate environment for aerobic vaginitis to set place [2, 27].

In cases of pregnancy, aerobic vaginitis is known to be associated with an increased risk of preterm labor and chorioamnionitis [5]. Although all three pregnancies infected by ESBL producers resulted in preterm labor in this study, due to the small number of included patients and the omission of cases without genital tract infection, the role of ESBL producers in poor pregnancy outcome should be interpreted with caution. Further studies including a larger number of pregnancies to elucidate the role of ESBL-producing E. coli in the genital tract infection is warranted.

Conclusions

In conclusion, a dominant clone of CTX-M type ESBL-producing E. coli in conjugative plasmids seems to be circulating in the community and considerable number of ST131 E. coli clone in the genital tracts of Korean women was noted. Sustained monitoring of molecular epidemiology and an adequate control of the clinically high-risk group is needed to prevent ESBL-producing E. coli from spreading throughout the community.

References

Gupta K, Stapleton AE, Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Fennell CL, Stamm WE. Inverse association of H2O2-producing lactobacilli and vaginal Escherichia coli colonization in women with recurrent urinary tract infections. J Infect Dis. 1998;178(2):446–50.

Han C, Wu W, Fan A, Wang Y, Zhang H, Chu Z, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic advancements for aerobic vaginitis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(2):251–7.

Obata-Yasuoka M, Ba-Thein W, Tsukamoto T, Yoshikawa H, Hayashi H. Vaginal Escherichia coli share common virulence factor profiles, serotypes and phylogeny with other extraintestinal E. coli. Microbiology. 2002;148:2745–52.

Watt S, Lanotte P, Mereghetti L, Moulin-Schouleur M, Picard B, Quentin R. Escherichia coli strains from pregnant women and neonates: Intraspecies genetic distribution and prevalence of virulence factors. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(5):1929–35.

Donders G, Bellen G, Rezeberga D. Aerobic vaginitis in pregnancy. BJOG. 2011;118(10):1163–70.

Kim YA, Kim JJ, Kim H, Lee K. Community-onset extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 131 at two Korean community hospitals: the spread of multidrug-resistant E. coli to the community via healthcare facilities. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;54:39–42.

Cha MK, Kang C, Kim SH, Cho SY, Ha YE, Wi YM, et al. Comparison of the microbiological characteristics and virulence factors of ST131 and non-ST131 clones among extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli causing bacteremia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;84:102–4.

Colpan A, Johnston B, Porter S, Clabots C, Anway R, Thao L, et al. Escherichia coli sequence type 131 (ST131) subclone H30 as an emergent multidrug-resistant pathogen among US veterans. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1256–65.

Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, McGarry SA, Trivette SL, Briggs JP, et al. Health care--associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:791–7.

Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: 26th Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100S (ISBN 1-56238-923-8). Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2016.

Lee K, Cho SR, Lee CS, Chong Y, Kwon OH. Prevalence of extended broad-spectrum beta-lactamase in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia. Korean J Infect Dis. 1994;26:341–8.

Ryoo NH, Kim E, Hong SG, Park YJ, Lee K, Bae IK, et al. Dissemination of SHV-12 and CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamase among clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae and emergence of GES-3 in Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:698–702.

Johnson JR, Clermont O, Johnston B, Clabots C, Tchesnokova V, Sokurenko E, et al. Rapid and specific detection, molecular epidemiology, and experimental virulence of the O16 subgroup within Escherichia coli sequence type 131. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:1358–65.

Park YS, Bae IK, Kim J, Jeong SH, Hwang S, Seo Y, et al. Risk factors and molecular epidemiology of community-onset extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli bacteremia. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:467–75.

Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;63:219–28.

Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:657–86.

Johnson JR, Johnston B, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA, Castanheira M. Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 as the major cause of serious multidrug-resistant E. coli infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:286–94.

Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1–14.

Kim D, Ahn JY, Lee CH, Jang SJ, Lee H, Yong D, et al. Increasing resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins, fluoroquinolone, and carbapenem in gram-negative bacilli and the emergence of carbapenem non-susceptibility in Klebsiella pneumoniae: analysis of Korean antimicrobial resistance monitoring system (KARMS) data from 2013 to 2015. Ann Lab Med. 2017;37:231–9.

Carlet J. The gut is the epicentre of antibiotic resistance. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;271:1–7.

Karanika S, Karantanos T, Arvanitis M, Grigoras C, Mylonakis E. Fecal colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:310–8.

Hong KH, Hong SK, Cho SI, Ra E, Han KH, Kang SB, et al. Analysis of the vaginal microbiome by next-generation sequencing and evaluation of its performance as a clinical diagnostic tool in vaginitis. Ann Lab Med. 2016;36:441–9.

Iredell J, Brown J, Tagg K. Antibiotic resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: Mechanisms and clinical implications. BMJ. 352:h6420. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6420.

Xia L, Liu Y, Xia S, Kudinha T, Xiao S-n, Zhong N-s, et al. Prevalence of ST1193 clone and an IncI1/ST16 plasmid in E. coli isolates carrying a blaCTX-M-55 gene from urinary tract infections patients in China. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44866.

Kim JS, Kim S, Park J, Shin E, Yun Y, Lee D, et al. Plasmid-mediated transfer of CTX-M-55 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase among different strains of Salmonella and Shigella spp. in the Republic of Korea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;89:86–8.

Vila J, Sáez-López E, Johnson JR, Römling U, Dobrindt U, Cantón R, et al. Escherichia coli: an old friend with new tidings. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2016;40:437–63.

Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SSK, McCulle SL, et al. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci US. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4680–7.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hae Yong Park from the department of policy research affairs, National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital for the statistical support.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the National health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital (NHIMC2017CR001).

Availability of data and materials

All data concerning this study is included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JEC handled the clinical part including taking the vaginal swab and reviewing the medical records. YAK worked on the microbiological part of this study. For the critical revision and approval of the final version, KL contributed. All three authors have read the final manuscript and hereby approve the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital (NHIMC IRB 2017–02-003). As it was a retrospective study with the review of electronic medical record without revealing the patient’s private information, the informed consent was waived.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Primer sequences for ESBL genotyping used in this study. Target genes, primer name, and primer sequences are shown. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Genetic information and antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli from female genital tract. Detailed information concerning the 91 E.coli specimens is included. (DOCX 40 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y.A., Lee, K. & Chung, J.E. Risk factors and molecular features of sequence type (ST) 131 extended-Spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in community-onset female genital tract infections. BMC Infect Dis 18, 250 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3168-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3168-8