Abstract

Background

Information on the hemoglobin status of pregnant and lactating mothers was scarce. The objectives of this study were to determine the burden and determinants of anemia in the pregnant and lactating mother.

Methods

A comparative cross-sectional study was conducted. Descriptive statistics were used to identify the prevalence of anemia. Binary logistic regression and multiple linear regressions were used to identify the predictors of anemia.

Results

The prevalence of anemia in lactating and pregnant women was 43.00% (95% CI {confidence interval}, 41% - 45%) and 84% of anemia was microcytic and hypocromic anemia. Anemia in lactating and pregnant women was positively associated with malaria infection [AOR{adjusted odds ratio} 3.61 (95% CI: 2.63–4.95)], abortion [AOR 6.63 (95% CI: 3.23–13.6)], hookworm infection [AOR 3.37 (95% CI: 2.33–4.88)], tea consumption [AOR 3.63 (95% CI: 2.56–5.14)], pregnancy [AOR 2.24 (95% CI: 1.57–3.12)], and Mid-upper arm circumference [B 0.36 (95% CI: 0.33, −0.4)]. Anemia in pregnant and lactating mother was negatively associated with urban residence [AOR 0.68, (95% CI: 0.5–0.94)], iron supplementation during pregnancy [AOR 0.03 (95% CI, 0.02–0.04)], parity [B -0.18 (95% CI: -0.23, −0.14)], age [B -0.03 (95% CI: -0.04, −0.03)].

Conclusion

The burden of anemia was higher in pregnant women than lactating women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anemia is a condition in which the hemoglobin concentration of a woman is less than 11 g/dl (gram per deciliter). World health organization report indicated that 20–50% of the world population was affected by iron deficiency anemia [1, 2]. Anemia was one of the great public health burdens for pregnant women affecting 56 million pregnant women globally [3, 4]. In the developed countries, 18% of pregnant women were anemic but in developing countries, 35–75% of pregnant women were anemic [5, 6].

Anemia during pregnancy has many adverse outcomes for the mother and her child. Globally, anemia resulted in the death of 115,000 mothers and 591,000 perinatal mortality annually [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Anemia during pregnancy predisposes mother to prolonged labor, abnormal delivery, increases the risk of hemorrhage [13,14,15]. Also, anemia increases the risk of infection to pregnant women due to its effect on the immune system [11, 16,17,18,19,20]. Newborns receive a number of complications as a result of maternal anemia. Among others, maternal anemia increases the risk of perinatal mortality and morbidity, preterm deliveries, low birth weight baby, intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

The burden of anemia varies from country to country; in Germany, 51% of pregnant women were anemic, in Trinidad and Tobago 15%, in Nepal 72.6% and 58% in India [32,33,34,35]. In Africa, more than 60% of pregnant women were anemic: in Ghana 44% of pregnant women, in Benin 24.3% of pregnant women, in Kenya 69.1% of pregnant women and in eastern Sudan 80.3% of pregnant women were anemic [36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Ethiopia is among country highly affected by anemia: the prevalence of anemia among pregnant women ranges from 15%-63%, in lactating mothers the prevalence of anemia was 22.3% [4, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

Finding from different scholars globally revealed that anemia in pregnancy was associated with gestational age, iron supplementation during pregnancy, wealth quintile, gravidity, mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC), age, residence, history of malaria infection, hookworm infection, parity, history of abortion, chronic inflammatory disorders, use of insecticide-treated bed net, tea consumption and use of animal product [33, 34, 39, 41, 42, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55].

Even if anemia resulted in these entire adverse outcomes for pregnant mother and their children, information on hemoglobin status of pregnant and lactating mothers are scarce. Due to lack of information decision makers are not capitalizing on the problem of anemia in pregnancy and lactating mother. This study is designed to attempt to fill these gaps. The objectives of this study were to compare the prevalence of anemia among pregnant and lactating women. Furthermore, the study attempted to identify the determining factors of anemia in pregnant and lactating mother and these aims were achieved successfully.

Methods

Health facility-based comparative cross-sectional study was conducted. The study was conducted in the city of Bahir dar, the capital of the Amhara regional state, located at the geographical coordinates of 11° 38′ north latitude and 37° 15′ east longitude, which is located approximately 560 km (km) northwest of Addis Ababa. The target populations were all pregnant and lactating mother in the city of Bahir dar and the study population were those presenting themselves for medical help. Pregnant or lactating mother unable to communicate were excluded from the study. The sample size was calculated using Epi-info software version 7 using the assumption of 95% confidence interval, pregnant to lactating mother ratio of 2:1, the proportion of anemia among lactating mother 22.3% [46], a power of 90%, an odds ratio of 1.5 and a non-response rate of 10%. Finally, the estimated sample size was 567 pregnant women and 1133 lactating women. Study participants were selected from health facilities of Bahir dar city. Stratified sampling technique was used to select study participants from each health facility. The data were collected from November 2014–May 2015. The data collection procedures contained two parts, exit interview and collecting blood and stool samples. For the interview part, first, the questionnaire was prepared in English then translated to Amharic (local language) then back to English to keep its consistency. The interview was conducted by 10 nurses professional and supervised by 3 health officers. The blood and stool samples were collected by 5 first degree holder laboratory technologists and supervised by two second degree holder laboratory technologists. From each woman, one gram stool sample was collected in 10 ml (ML) SAF (sodium acetate- acetic acid-formalin solution). Concentration technique was used. The stool sample was well mixed and filtered using a funnel with gauze then centrifuged for one minute at 2000 RPM (revolution per minute) and the supernatant was discarded. 7 ML normal saline was added, mixed with a wooden stick, 3 ML ether was added and mixed well then centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 RPM. Finally, the supernatant was discarded and the whole sediment was examined for parasites [56]. 1 ML blood sample was collected from each woman following standard operational procedures to measure their hemoglobin level and red blood cell indices using Mindray hematology analyzer. To maintain the quality of the data; pretest was conducted in 50 parents, training was given to data collectors and supervisors and the whole data collection process was closely supervised by the investigator and supervisors. The collected data were checked for completeness. The data were entered into the computer using Epi-info software and analyzed using statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software. Descriptive statistics were used to estimate the prevalence of anemia among pregnant and lactating women. Binary logistic regression and multiple linear regressions were used to identify the determinants of anemia.

Ethical clearance was granted from Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau ethical committee. Legal permission was obtained from each health center. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. The confidentiality of the data was kept at all steps. Women with intestinal parasites or low hemoglobin concentration (<11 g/dl) were referred to the nearby health center for further management.

Results

A total of 1651 women was included giving a response rate of 97.12%. The mean age of the respondents was 22.65 years (SD [standard deviation] 5.12 years). Orthodox Christian constituted 96.7% (1596) of study participants, 90.1% of study participants were Amhara by ethnicity, 52.7% of women were from urban areas, and 49.3% of study participants were house wife by their occupation (Table 1).

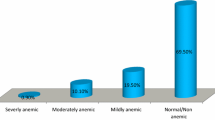

Anemia in pregnant women

A total of 550 pregnant women was included giving a response rate of 97%. The mean age of pregnant women was 26.88 years (SD = 5.82 years). After adjusting for women’s residence, history of abortion, history of malaria, occupation, hookworm infection, tea consumption and iron supplementation during pregnancy: the risk of anemia increases in rural women, history of abortion or malaria, hookworm infection, and tea consumptions. The risk of anemia was lower in women with government employer, in women that were supplied by iron during pregnancy (Table 2).

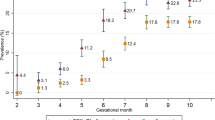

On linear regression anemia in pregnancy was associated with age, gravidity, mid-upper arm circumferences (MUAC) and gestational age (Table 3).

The degree of anemia defers with the gestational age of pregnant mothers, per one week increase in the age of gestation her hemoglobin concentration will decrease by 0.02 g/dl. That means the higher the gestational age the risk of becoming anemic will also become high.

Anemia in lactating women

A total of 1101 lactating women were included with a response rate of 97.18%. The mean age of the lactating women was 20.54 years (SD 3.12 years). On binary logistic regression after adjusting for residence, history of malaria, history of abortion, hookworm infection, iron supplementation, tea consumption: anemia in lactating women was associated with a residence, history of malaria, history of abortion, iron supplementation and tea consumption (Table 4).

On linear regression hemoglobin concentration in pregnancy was associated with MUAC, parity, age, and frequency of breastfeeding per 24 h (Table 5).

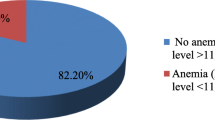

Anemia in pregnant and lactating women

The prevalence of anemia in lactating and pregnant women was 43% (95% CI, 41%-45%), 84% of anemia was microcytic hypocromic, 4.54% of anemia was macrocytic hypercromic, and 5.82% of anemia was normocytic normocromic (Table 6).

After adjusting for residence, pregnancy, history of malaria, history of abortion, hookworm infection, iron supplementation during pregnancy, tea consumption, occupation and educational status; anemia in pregnant or lactating mother were associated with a residence, pregnancy, history of malaria, history of abortion, hookworm infection, iron supplementation during pregnancy and tea consumption (Table 7).

On linear regression determinants of anemia in pregnant or lactating women were associated with mid-upper arm circumferences, age, and parity of pregnant or lactating women (Table 8).

Discussion

The prevalence of anemia in lactating and pregnant women was 43% (95% CI, 41%-45%) and 84% of anemia was iron deficiency anemia followed by normocytic normocromic anemia This finding is lower when compared to findings from eastern Ethiopia [48] Germany [32], Nepal [33], India [35], eastern Sudan [40], Kenya [41]; agrees with findings from Ghana [39]and higher than finding from northern Ethiopia [49] southern Ethiopia [45] Trinidad and Tobago [34], Benin [42]. These might be due to the reason that different distribution of determinants of anemia across different social, cultural or geographical areas.

The risk of anemia in rural Lactating or pregnant women was 32% higher as compared to urban lactating or pregnant women [AOR 0.68, (95% CI: 0.5–0.94)]. This finding agrees with finding from northern Ethiopia [49]. This is due to the reason that women in the rural areas are in low socio-economic status so that they have no access to use iron rich foods [48].

Malaria infected women had 3.61 folds higher risk of anemia as compared to women with no history of malaria infection [AOR 3.61(95% CI: 2.63–4.95)]. This finding agrees with finding from north Ethiopia [49], Nepal [33], Ghana [52]. This is due to the fact that Plasmodium species ingests the red blood cells of the host and finally decreases the number of red blood cells.

Abortion increases the risk of anemia by 6.63 folds higher [AOR 6.63 (95% CI: 3.23–13.6)]. This finding agrees with finding from Trinidad and Tobago [34]. This is due to the reason that abortion increases the risk of hemorrhage.

Hookworm infection increases the risk of anemia by 3.37 folds higher [AOR 3.37 (95% CI: 2.33–4.88)]. This finding agrees with findings from northern Ethiopia [49], Nepal [33]. This is due to the fact that hookworm causing parasites significantly depletes the red blood cell of the host.

Iron supplementation during pregnancy decreases the risk of anemia by 97% [AOR 0.03 (95% CI: 0.02–0.04)]. The main reason for not receiving iron during pregnancy was unavailability of the drug. This finding agrees with finding from eastern Ethiopia [48]. This is due to the reason that iron act as a predominant role in the production of red blood cells.

Tea consumption increases the risk of anemia 3.63 folds higher [AOR 3.63 (95% CI: 2.56–5.14)]. This finding agrees with finding from Ethiopia [55]. This is because the fact that tea contains chemicals that inhibit the absorption of iron [57].

Pregnant mother had 2.24 folds higher risk of anemia than lactating mother [AOR 2.24 (95% CI: 1.57–3.12)]. This is due to the reason that after the delivery the mother has access to foods, especially animal products so that they can get more foods than when she was pregnant. In addition, mother can be treated for hookworm after delivery; during pregnancy, hookworm was not treated because the drug has a teratogenic effect.

MUAC had a positive relationship with hemoglobin concentration. Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) increase the hemoglobin concentration of women will also increase [B 0.36 (95% CI: 0.33, −0.4)]. This finding agrees with finding from eastern Ethiopia [48] signaling that MUAC can be used to evaluate the nutritional level of pregnant or lactating women.

As the parity of women increases their hemoglobin concentration decreases [B -0.18 (95% CI: -0.23, −0.14)].

This finding agrees with finding from the republic of Seychelles [53], Trinidad and Tobago [34], Benin [42]. This is due to the reason that as the number of pregnancy increases the risk of ante-partum hemorrhage and postpartum hemorrhage for the women became high.

The age of the women and her hemoglobin concentration had negative relationships. As the age increases the risk of becoming anemic would be high [B -0.03 (95% CI:-0.04, −0.03)]. This finding agrees with finding from Benin [42], northern Ethiopia [49]. This is due to the reason that as the age of the mother increases her parity wills also increases.

The main limitation of this study might be recall bias, but the interview was conducted using a structured questionnaire and the interviewers were trained health professionals they can probe and make the respondents remember the issues.

Conclusion

Both pregnant and lactating mothers were affected by anemia and the burden of anemia is higher in the pregnant mother than the lactating mother and iron deficiency anemia is the most common type of anemia. Anemia in pregnancy and lactation was determined by a history of malaria, history of abortion, hookworm infection, tea consumption, MUAC, residence, iron supplementation during pregnancy, parity, and age.

Recommendation

Iron supplementation should be given both to pregnant and lactating mothers. Iron supplementation should be included as part of malaria treatment in women with malaria. Women are advised to avoid tea during their pregnancy and lactation period. Scholars should consider MUAC as an alternative tool to detect nutritional defects in pregnancy.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- B:

-

Beta Coefficients

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COR:

-

Crude Odds Ratio

- G/DL:

-

Gram per Deciliter

- IUGR:

-

Intra Uterine Growth Retardation

- KM:

-

Kilometer

- MCHC:

-

Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration

- MCV:

-

Mean Corpuscular Volume

- ML:

-

Milliliter

- MUAC:

-

Mid Upper Arm Circumference

- RPM:

-

Revolution per Minute

- SAF:

-

Sodium Acetate- Acetic Acid-Formalin Solution

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Science

References

Gopalan C. Strategies for combating under nutrition: lessons learned for the future. In: Nutrition in developmental transition in Southeast Asia. New Delhi: World Health Organization; 1992. p. 109–11.

Patterson A, Brown W, Roberts D. Dietary and supplement treatment of iron deficiency results in improvements in general health and fatigue in Australian women of childbearing age. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20(4):337–42.

Balarajan Y, Ramakrishnan U, Ozaltin E, Shankar A, Subramanian V. Anaemia in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378(9809):2123–35.

WHO: World wide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005, vol. 1. Atlanta CDC; 2008.

WHO: The prevalence of anaemia in women: a tabulation of available information. In. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

WHO: World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Worldwide Prevalence of Anemia:. In: WHO Global Database of Anemia. 2008.

Salhan S, Tripathi V, Singh R, Gaikwad H. Evaluation of hematological parameters in partial exchange and packed cell transfusion in treatment of severe anemia in pregnancy. Anemia. 2012;2012:1–7.

DeBenoist B, McLean E, Egli I, Cogswell M: Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993-2005. In: WHO Global database on anaemia. World health Organization; 2008.

Weiss G, Goodnough L. Anemia of chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1011–23.

Bernard B, Mohammad H, David P. An analysis of anemia and pregnancy-related maternal mortality. J Nutr. 2001;131:604S–15S.

Megan OB, Roland K, Gernard M, Elmar S, David H, Wafaie F, Anemia I. An independent predictor of mortality and immunologic progression of disease among women with HIV in Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(2):219–26.

Allen L. Anemia and iron deficiency: effects on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5 Suppl):1280S–12804S.

Malhotra M, Sharma J, Batra S, Sharma S, Murthy N, Arora R. Maternal and perinatal outcome in varying grades of anemia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2002;79(2):93–100.

Meuris S, Piko B, Eerens B, Vanbellinghen P, Dramaix A, Hennart P. Gestational malaria: assessment of its consequences on fetal growth. Am J Tropical Medicane and Hygiene. 1993;48:603–9.

Kumar A. National nutritional anaemia control programme in India. Indian J Public Health. 1999;43:3–5.

Stephen O. Iron and its relation to immunity and infectious disease. J Nutr. 2001;131:616S–35S.

Allen L. Anemia and iron deficiency: effects on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(5 Suppl):S1280–4.

Ramussen K. Is there a causal relationship between iron deficiency or iron deficiency anaemia and weight at birth, length of gestation and perinatal mortality? J Nutr. 2001;131(2 Suppl):S590–603.

Letsky E. Maternal anaemia in pregnancy, iron and pregnancy – a haematologist’s viewpoint. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 2001;12:159–75.

Elise L. Maternal hemoglobin concentration and pregnancy outcome: a study of the effects of elevation in el alto. Bolivia MJM. 2010;13(1):47–55.

WHO. Nutritional anaemias. In: World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. vol. 405. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1968.

CDC: Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. In: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. vol. 47: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998: 1–29.

Steer P. Maternal hemoglobin concentration and birth weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(suppl):1285S–7S.

Goldenberg R, Tamura T, DuBard M, Johnston K, Copper R, Neggers Y. Plasma ferritin and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1356–9.

Luke B. Nutritional influences on fetal growth. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;37(3):538–49.

Ashok K, Arun KR, Sriparna B, Debabrata D, Jamuna SS. Cord blood and breast milk iron status in maternal anemia. Pediatrics. 2008;121(3):673–80.

Ismail M, Ordi J, Menendez C, Ventura P, Aponte J, Kahigwa E, Hirt R, Cardesa A, Alonso A. Placental pathology in malaria: a histological, immunohistochemical, and quantitative study. Hum Pathol. 2000;31:85–93.

Verhoeff F, Brabin B, Van-Buuren S, Chimsuku L, Kazembe P, Wit J, Broadhead R. An analysis of intra-uterine growth retardation in rural Malawi. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:682–9.

Yarlini B, Subramanian S, Fawzi W. Maternal iron and folic acid supplementation is associated with lower risk of low birth weight in India. J Nutr. 2013;143:1309–15.

Adam I, Babiker S, Mohmmed A, Salih M, Prins M, Zaki Z. Low body mass index, anaemia and poor perinatal outcome in a rural hospital in eastern Sudan. J Trop Pediatr. 2008;54:202–4.

Brabin B, Piper C. Anaemia and malaria attributable low birth weight in two populations in Papua New Guinea. Ann Hum Biol. 1997;24:547–55.

Bergmann R, Gravens-Muller L, Hertwig K, Hinkel J, Andres B, Bergmann K. Iron deficiency is prevalent in a sample of pregnant women at delivery in Germany. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102(2):155–60.

Michele D, Rebecca S, Jaya S, Elizabeth P, Steven L, Subarna K, Sharada S, Joanne K, Marco A, Keith W. Hookworms, malaria and vitamin a deficiency contribute to anemia and iron deficiency among pregnant women in the plains of Nepal. J Nutr. 2000;130:2527–36.

Uche-Nwachi E, Odekunle A, Jacinto S, Burnett M, Clapperton M, David Y, Durga S, Greene K, Jarvis J, Nixon C, et al. Anaemia in pregnancy: associations with parity, abortions and child spacing in primary healthcare clinic attendees in Trinidad and Tobago. Afr Health Sci. 2010;10(1):66–70.

Balarajan Y, Fawzi W, Subramanian S. Changing patterns of social inequalities in anaemia among women in India: cross sectional study using nationally representative data. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002233.

Vanden-Broek N, White S, Neilson J. The relationship between asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus infection and the prevalence and severity of anemia in pregnant Malawian women. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:1004–7.

Massawe S, Urassa E, Lindmark G. Anaemia in pregnancy: a major health problem with implications for maternal health care. Afr J Health Sci. 1996;3:126–32.

Massawe S, Urassa E, Lindmark G. Effectiveness of primary level antenatal care in decreasing anemia at term in Tanzania. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1999;78:573–9.

Frank M, Birgit R, Matthias G, Stefknie B, Holger T, Elisabeth K, William T, Ulrich B. Anaemia in pregnant Ghanaian women: importance of malaria, iron deficiency, and haemoglobinopathies. Transactions Ofthe Royal Society Of Tropical Medicine And Hygiene. 2000;94:477–83.

Ishraga A, Gamal A, Ahmed M, Magdi S, Naji A, Mustafa E, Ishag A. Anaemia, folate and v itamin B12 deficiency among pregnant women in an area of unstable malaria transmission in eastern Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:493–6.

Peter O, Anna V-E, Mary H, Monica P, John A, Kephas O, Piet K, Laurence S. Malaria and anaemia among pregnant women at first antenatal clinic visit in Kisumu, western Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(12):1515–23.

Od S¨l, Ghislain K, Manfred A, Florence B-L, Achille M, Michel C. Maternal Anemia at First Antenatal Visit: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Malaria-Endemic Area in Benin. AmJTropMedHyg. 2012;87(3):418–24.

Jemal H, Rebecca P. Iron deficiency anemia is not a rare problem among women of reproductive ages in Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Blood Disorders. 2009;9(7):1–8.

Gies S, Brabin B, Yassin M, Cuevas L. Comparison of screening methods for anaemia in pregnant women in Awassa, Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8(4):301–9.

Gibson R, Abebe Y, Stabler S, Allen RH, Westcott JE, Barbara JS, Nancy FK, MH K. Zinc, gravida, infection, and iron, but not vitamin B-12 or folate status, predict hemoglobin during pregnancy in southern Ethiopia. J Nutr. 2008;138:581–6.

Haidar J, Nelson M, Abiud M, Ayana G. Malnutrition and iron deficiency Anaemia in urban slum communities form Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. East Afri Med J. 2003;80(4):191–4.

Umeta M, Haidar J, Demissie T, Akalu G, Ayana G. Iron deficiency Anaemia among women of reproductive age in nine administrative regions of Ethiopia. EthiopJHealth Dev. 2008;22(3):252–8.

Alene KA, Dohe AM. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in an urban area of eastern Ethiopia. Anemia. 2014;2014:1–8.

Alem M, Enawgaw B, Gelaw A, Kena T, Seid M, Olkeba Y. Prevalence of anemia and associated risk factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Azezo health center Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia. J Interdiscipl Histopathol. 2013;1(3):137–44.

Mbonye AK, Bygbjerg I, Magnussen P. Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: a community-based delivery system and its effect on parasitemia, anemia and low birth weight in Uganda. Int J Infect Dis. 12(1):22–9.

Nynke B, Elizabeth L. Etiology of anemia in pregnancy in south Malawi. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72(suppl):247S–56S.

Lena H, Christa V-O, George B-A, Ville H, Patrick A, Teunis E, Ulrich B, Frank M. Decline of placental malaria in southern Ghana after the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy. Malar J. 2007;6(144)

Emeir D, Maxine B, Julie W, Chin-Kuo C, Paula R, Gary M, Philip D, Thomas C, Conrad S, Strain J. Iron status in pregnant women in the Republic of Seychelles. Public Health Nutr. 2009;13(3):331–7.

MacLeod C: Intestinal nematode infections. In: Parasitic Infections in Pregnancy and the Newborn New York: MacLeod, C. L., ed; 1988.

Haidar J. Prevalence of Anaemia, deficiencies of iron and folic acid and their determinants in Ethiopian women. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28(4):359–68.

Institute S: Methods in Parasitology. In: Sodium acetate-acetic acid-formalin solution method for stool specimen. Basel: Swiss TPH: Swiss Tropical Institute; 2005: 1–18.

Iron Deficiency Anemia: Nutritional Considerations [http://www.nutritionmd.org/consumers/hematology/iron_anemia_nutrition.html].

Acknowledgements

Our heartfelt appreciation goes to federal democratic republic of Ethiopia ministry of health for their financial support. We would like to acknowledge the Amhara national regional state health bureau for their unreserved support during this work. We would like to acknowledge staffs in the health center of Bahir dar for their cooperation during the data collection period. At last but not least we would like to acknowledge all institutions and organization that had input for this work.

Funding

This research work was financially supported by federal democratic republic of Ethiopia ministry of health. The funder has no role in design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

‘The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BEF conceived the experiment; BEF and TEF performed the experiment, plan the data collection process, analyzed and interpreted the data. BEF and TEF wrote the manuscript and approved the final draft for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Bahir Dar University ethical review committee. Permission to conduct the study was also obtained from the Amhara national regional state health bureau. Written consent was obtained from participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declares that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Feleke, B.E., Feleke, T.E. Pregnant mothers are more anemic than lactating mothers, a comparative cross-sectional study, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. BMC Hematol 18, 2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12878-018-0096-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12878-018-0096-1