Abstract

Background

Immediate bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is essential for survival from sudden cardiac arrest (CA). Current CPR guidelines recommend that dispatchers assist lay rescuers performing CPR (dispatch-assisted CPR (DACPR)), which can double the frequency of bystander CPR. Laypersons, however, are not familiar with receiving CPR instructions from dispatchers. DACPR training can be beneficial for lay rescuers, but this has not yet been validated. The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of simple DACPR training for lay rescuers.

Methods

We conducted a DACPR simulation pilot study. Participants who were non-health care professionals with no CPR training within 1 year prior to this study were recruited from Nara Medical University Hospital. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the two 90-min adult basic life support (BLS) training course groups: DACPR group (standard adult BLS training plus an additional 10-min DACPR training) or Standard group (standard adult BLS training only). In the DACPR group, participants practiced DACPR through role-playing of a dispatcher and an emergency caller. Six months after the training, all subjects were asked to perform a 2-min CPR simulation under instructions given by off-duty dispatchers.

Results

Out of the 66 participants, 59 completed the simulation (30 from the DACPR group and 29 from the Standard group). The CPR quality was similar between the two groups. However, the median time interval between call receipt and the first dispatch-assisted compression was faster in the DACPR group (108 s vs 129 s, p = 0.042).

Conclusions

This brief DACPR training in addition to standard CPR training can result in a modest improvement in the time to initiate CPR. Future studies are now required to examine the effect of DACPR training on survival of sudden CA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sudden cardiac arrest (CA) is a leading cause of death in industrialized nations. Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) can increase the chance of survival from out-of-hospital CA (OHCA) [1,2,3]. Bystander CPR, however, is initiated only 10–40% in the USA, Europe, and Asia [2, 4, 5].

Dispatchers can help untrained emergency callers identify CA and instruct them to start prompt chest compression [6]. It is reported that dispatch-assisted CPR (DACPR) may double the frequency of CPR initiation by bystanders [7]. Familiarizing laypersons with DACPR may allow lay rescuers to perform CPR more quickly. However, the effectiveness of adding DACPR training to standard CPR training, in terms of strengthening bystander CPR, has not been deeply investigated.

In order to highlight the effect of DACRP training for lay rescuers, we conducted a randomized pilot study for DACPR training.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a parallel randomized pilot study to compare DACPR quality among participants from two CPR trainings: a standard CPR training and a standard CPR training with an additional DACPR training. We recruited non-health care professionals with no CPR training experience within 1 year prior to this study from Nara Medical University Hospital.

CPR trainings

The training sessions were held at Nara Medical University. The first cohort was given standard adult basic life support (BLS) training (Standard group), while the second cohort was given standard adult BLS training with an additional 10-min DACPR training (DACPR Group). In the DACPR group, participants learned DACPR through caller-dispatcher role-playing with CPR manikins and a template for CPR instruction at the end of the training. Both training courses were 90 min. The participants were assigned to one of the adult BLS trainings randomly scheduled based on a computer program. The training sessions took place in a room at the university, where a maximum of 10 people can learn CPR. All the participants were blinded to their allocations. Six months after the trainings, all participants were invited to the DACPR simulation via phone.

DACPR simulation

We conducted DACPR simulation 6 months after the training. In this simulation, the participants performed a single rescuer scenario in a small room at Nara Medical University. In this room, there was a manikin (Laerdal Resusci Anne manikin with Skill Reporting System) lying on a hard floor and a cordless extension phone on a small table. Neither an AED nor other rescuers were present for this simulation. After being given a list of simple instructions (Appendix 1), the participants entered the room as if they happened to find someone (CPR manikin) unconscious on the floor; they then performed CPR under the instruction of dispatchers. Nine dispatchers with at least 1 year of emergency dispatch experience took part in this simulation. All dispatchers were blinded to the participants’ allocations between the two cohorts. The study dispatchers provided CPR instructions along with the standard DACPR guidelines prepared by the Japanese Fire and Disaster Management Agency [8] after giving the simulation instruction (Appendix 2). The study participants and dispatchers communicated through a closed telephone line system for emergency call training. The study investigators recorded the time and ensured that 2 min was kept for each simulation. After performing the simulation, each participant was offered a $10 value gift card as an incentive for the simulation.

Data collection and outcome

Data for chest compression performance (mean depth [mm], mean rate [cpm, compression per minute], hand position [%]) were collected through the Laerdal Skill Reporting System®. All simulations were recorded on video cameras (SONY HDR-AS 200V). The following time intervals were measured: [1] the call to identify the need for CPR, [2] the call to start CPR instruction, and [3] the call to start the first chest compression. The outcome of this study was the effect of DACPR on time interval between call receipt and the first chest compression, and the quality of chest compressions.

Statistics

Since this study was a pilot study, the target sample size was 30 in each group with reference to the previous studies [9,10,11,12,13,14].

Continuous variables were described as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables were described as number (percentages). We used Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Two-tailed p values less than 0.05 were considered as significant. Data analysis was done by SPSS ver. 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

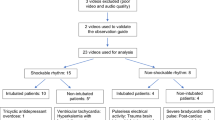

A total of 66 participants, aged 20s to 50s, were recruited and randomly assigned to the study groups (N = 34; 17 males, DACPR group and N = 32; 15 males, Standard group). After 6 months, 59 participants completed the DACPR simulation (N = 30; 15 males, DACPR group and N = 29; 13 males, Standard group, Fig. 1). The results are shown in Table 1. The overall chest compression performances were similar between the two groups. The average compression depth in both groups did not meet the recommended standard of 5 cm. The median time intervals between the call and the dispatchers’ recognition of CA, and call to the start of CPR instruction, were prompt in both groups, but relatively faster in the DACPR group (23.5 s vs 27 s, p = 0.187; 79.5 s vs 93 s, p = 0.069, respectively). The median time intervals between the call receipt and the start of chest compressions was significantly faster in the DACPR group (108 s) compared to the Standard group (129 s, p = 0.042) (Table 2).

Discussion

In this simulation study, participants from the DACPR training group demonstrated faster initiation of CPR with dispatcher instructions 6 months after training, when compared to the standard CPR training group. This result indicates that this brief DACPR training for lay rescuers has a potential benefit on CPR education.

The median time interval from call to first chest compression was 21 s faster in the DACPR group than in the Standard CPR group (108 s vs 129 s, p = 0.042). Kim et al. conducted a similar randomized simulation study to compare the effects of DACPR training to standard CPR training on the quality of DACPR. Consistently, Kim et al. also found that participants who underwent DACPR training started chest compressions 20 s faster than those who underwent standard CPR training, in a simulation that occurred 6 months after the initial training [9]. A possible explanation for this time reduction is that participants in the DACPR group were more familiar with the dispatcher instructions for CPR. For Standard CPR group participants, this DACPR simulation was their first experience to follow the instruction. Whether this 21-s reduction in the start of CPR represents a meaningful change in terms of the clinical outcomes of CA now warrants investigation. Studies have shown that it takes 3 to 4 min to start CPR when callers receive dispatch instruction in real-life situations [15, 16]. DACPR training for lay rescuers might be of clinical significance since the chance of survival with good neurological outcome for sudden CA victims decreases by 7–10% every minute without CPR [17].

Other key elements of chest compression such as median depth, rate, fraction, and the proportion of correct hand positions were similar in the two groups. Among these key elements, chest compression depth was suboptimal in both groups. Several simulation studies on layperson CPR training have shown that the quality of chest compressions rarely meet the recommended standard [10, 11], even with dispatch assistance [9, 12]. Dispatch CPR instruction to achieve optimal chest compression depths needs further studies.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size is small and the results are difficult to generalize. Second, this simulation was conducted at just 6 months after training; as such, the long-term effects of DACPR training remain to be investigated. Future studies that look at skill retention after 12 months or the effect of repeated DACPR training are thus warranted. Finally, the findings of our study might not be generalized to the entire population as our study cohort predominantly included young participants in their 20s to 50s. Most CA patients and callers are likely to be elderly in residential settings [18] and might not be able to perform DACPR promptly.

Conclusions

This pilot study suggests that DACPR training for 10 min in addition to standard CPR training can result in a modest improvement in the time to initiate CPR. Future studies are now required to examine the effect of DACPR training on survival of sudden CA.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CA:

-

Cardiac arrest

- OHCA:

-

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- DACPR:

-

Dispatch-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- EMS:

-

Emergency medical services

References

Iwami T, Nichol G, Hiraide A, Hayashi Y, Nishiuchi T, Kajino K, et al. Continuous improvements in “chain of survival” increased survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrests: a large-scale population-based study. Circulation. 2009;119:728–34.

Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F, Weeke P, Hansen CM, Christensen EF, et al. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2013;310:1377–84.

Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:63–81.

Song KJ, Shin SD, Park CB, Kim JY, Kimdo K, Kim CH, et al. Dispatcher-assisted bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a metropolitan city: a before-after population-based study. Resuscitation. 2014;85:34–41.

Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, Hedges J, Powell JL, Aufderheide TP, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–31.

Lerner EB, Rea TD, Bobrow BJ, Acker JE 3rd, Berg RA, Brooks SC, et al. Emergency medical service dispatch cardiopulmonary resuscitation prearrival instructions to improve survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:648–55.

Rea TD, Eisenberg MS, Becker LJ, Murray JA, Hearne T. Temporal trends in sudden cardiac arrest: a 25-year emergency medical services perspective. Circulation. 2003;107:2780–5.

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Fire and Disaster Management Agency [homepage on the internet]. Tokyo: Text book of emergency medical operation for communication dispatchers (in Japanese). [cited March 2020]. Available from: https://www.fdma.go.jp/neuter/about/shingi_kento/h25/kyukyu_arikata/pdf/text.pdf.

Kim TH, Lee YJ, Lee EJ, Ro YS, Lee KW, Lee H, et al. Comparison of cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality between standard versus telephone-basic life support training program in middle-aged and elderly housewives: a randomized simulation study. Sim Healthcare. 2018;13:27–32.

Blewer AL, Leary M, Esposito EC, Gonzalez M, Riegel B, Bobrow BJ, et al. Continuous chest compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation training promotes rescuer self-confidence and increased secondary training: a hospital-based randomized controlled trial*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:787–92.

Park SO, Hong CK, Shin DH, Lee JH, Hwang SY. Efficacy of metronome sound guidance via a phone speaker during dispatcher-assisted compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation by an untrained layperson: a randomised controlled simulation study using a manikin. Emerg Med J. 2013;30:657–61.

Spelten O, Warnecke T, Wetsch WA, Schier R, Bottiger BW, Hinkelbein J. Dispatcher-assisted compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation provides best quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation by laypersons: a randomised controlled single-blinded manikin trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000000432.

Mirza M, Brown TB, Saini D, pepper TL, Nandigam HK, Kaza N et al. instructions to “push as hard as you can” improve average chest compression depth in dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2008;79:97–102.

Painter I, Chavez DE, Ike BR, Yip MP, Tu SP, Bradley SM, et al. Changes to DA-CPR instructions: can we reduce time to first compression and improve quality of bystander CPR? Resuscitation. 2014;85:1169–73.

Lewis M, Stubbs BA, Eisenberg MS. Dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation: time to identify cardiac arrest and deliver chest compression instructions. Circulation. 2013;128:1522–30.

Dameff C, Vadeboncoeur T, Tully J, Panczyk M, Dunham A, Murphy R, et al. A standardized template for measuring and reporting telephone pre-arrival cardiopulmonary resuscitation instructions. Resuscitation. 2014;85:869–73.

Nagao K. Chest compression-only cardiocerebral resuscitation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15:189–97.

18. Swor RA, Jackson RE, Compton S, Domeier R, Zalenski R, Honeycutt L, et al. Cardiac arrest in private locations: different strategies are needed to improve outcome. Resuscitation. 2003;58:171–6.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank the dispatchers (Nara Wide Area Fire Department, Bureau of Fire Department of Nara City, and Ikoma Fire Department) who took part in this simulation study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Foundation for Ambulance Service Development, Tokyo, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HF and HA conducted the study design. HF and TS conducted the trainings and simulations. HA performed the statistical analysis. HF prepared this manuscript. HF, HA, TK, and FB finalized the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Nara Medical University.

All participants were informed about this study and written consents were obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to declare in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Instruction for Subjects

Please perform this simulation as if you were in a real emergency situation.

If you find a man (manikin) lying on the floor when you enter this room, act as you find a real person on the floor.

YOU ARE the ONLY PERSON in this room.

YOU CAN’T FIND ANYBODY.

Call the person on the floor.

If not responsive, DO WHAT YOU THINK YOU HAVE TO DO until We say ‘STOP’.

AED is not available in this room.

You may find a phone.

Emergency number is 119 in here.

If you feel uncomfortable or pain in the back, arms, elbows or hands, please notify us.

Now, you’ve heard ‘BANG’ behind this door.

ARE YOU READY?

HERE WE GO!

Appendix 2

Instruction for dispatchers

When you receive a call from the study subjects, act as you usually do. Except for the following;

You do not have to ask the caller where the address is. (This simulation is conducted as a private residential setting through a landline.)

When you realized that the call was cardiac arrest,

- 1)

Ask callers whether the patient is on a hard surface floor on the back.

- 2)

Ask callers to activate the speaker phone function.

- 3)

Ask callers to open the patient’s bear chest.

- 4)

And then start instruction for chest compression as you usually do.

- 5)

DO NOT INSTRUCT RESCUE BREATHING.

- 6)

Keep instructing for high quality compression until the simulation ends.

- 7)

This simulation ends two minutes after the caller started chest compression.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukushima, H., Asai, H., Seki, T. et al. The effect of 10-min dispatch-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation training: a randomized simulation pilot study. Int J Emerg Med 13, 31 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00287-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-020-00287-9