Abstract

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a complex disorder for which currently there is no accepted definition. Having a uniform standard for diagnosing and classifying AKI would enhance our ability to manage these patients. Future clinical and translational research in AKI will require collaborative networks of investigators drawn from various disciplines, dissemination of information via multidisciplinary joint conferences and publications, and improved translation of knowledge from pre-clinical research. We describe an initiative to develop uniform standards for defining and classifying AKI and to establish a forum for multidisciplinary interaction to improve care for patients with or at risk for AKI.

Methods

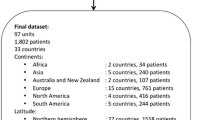

Members representing key societies in critical care and nephrology along with additional experts in adult and pediatric AKI participated in a two day conference in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, in September 2005 and were assigned to one of three workgroups. Each group's discussions formed the basis for draft recommendations that were later refined and improved during discussion with the larger group. Dissenting opinions were also noted. The final draft recommendations were circulated to all participants and subsequently agreed upon as the consensus recommendations for this report. Participating societies endorsed the recommendations and agreed to help disseminate the results.

Results

The term AKI is proposed to represent the entire spectrum of acute renal failure. Diagnostic criteria for AKI are proposed based on acute alterations in serum creatinine or urine output. A staging system for AKI which reflects quantitative changes in serum creatinine and urine output has been developed.

Conclusion

We describe the formation of a multidisciplinary collaborative network focused on AKI. We have proposed uniform standards for diagnosing and classifying AKI which will need to be validated in future studies. The Acute Kidney Injury Network offers a mechanism for proceeding with efforts to improve patient outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute renal failure (ARF) is a complex disorder that occurs in a variety of settings with clinical manifestations ranging from a minimal elevation in serum creatinine to anuric renal failure. It is often under-recognized and is associated with severe consequences [1–4]. Recent epidemiological studies demonstrate the wide variation in etiologies and risk factors [1, 5–7], describe the increased mortality associated with this disease (particularly when dialysis is required) [1, 4, 6, 8, 9], and suggest a relationship to the subsequent development of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and progression to dialysis dependency [1, 4, 8, 10–12]. Emerging evidence suggests that even minor changes in serum creatinine are associated with increased in-patient mortality [13–20]. ARF has been the focus of extensive clinical and basic research efforts over the last decades. The lack of a universally recognized definition of ARF has posed a significant limitation. Despite the significant progress made in understanding the biology and mechanism of ARF in animal models, translation of this knowledge into improved management and outcomes for patients has been limited.

During the last five years, several groups have recognized these limitations and have worked to identify the knowledge gaps and define the necessary steps to correct these deficiencies. These efforts have included consensus conferences and publications from the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) group [19, 21–25], the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) ARF Advisory group [26], the International Society of Nephrology (ISN), and the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) and KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) groups [27]. Additionally, the critical care societies have developed formal intersociety collaborations such as the International Consensus Conferences in Critical Care [28]. Recognizing that future clinical and translational research in ARF will require multidisciplinary collaborative networks, the ADQI group and representatives from three nephrology societies (ASN, ISN, and NKF) and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine met in Vicenza, Italy, in September 2004. They proposed the term acute kidney injury (AKI) to reflect the entire spectrum of ARF, recognizing that an acute decline in kidney function is often secondary to an injury that causes functional or structural changes in the kidneys. The group established the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) as an independent collaborative network comprised of experts selected by the participating societies to represent both their area of expertise and their sponsoring organization. AKIN is intended to facilitate international, interdisciplinary, and intersocietal collaborations to ensure progress in the field of AKI and obtain the best outcomes for patients with or at risk for AKI.

This report describes an interim definition and staging system for AKI and a plan for further activities of the collaborative network which were developed at the first AKIN conference held in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, in September 2005.

Materials and methods

Representatives of the major critical care and nephrology societies and associations and invited content experts were assigned to workgroups to consider three topics: (a) the development of uniform standards for definition and classification of AKI, (b) joint conference topics, and (c) the interdisciplinary collaborative research network. Each workgroup had an assigned chair and co-chair to facilitate the discussion and develop summary recommendations of the workgroup. The draft recommendations were then refined and improved during discussion with the larger group. Key points and issues were noted and then discussed a second time if no resolution was reached initially. When a majority view was not evident or when the area was felt to be of extreme importance, votes were tallied. Dissenting opinions were also noted. The final recommendations were circulated to all participants and subsequently agreed upon as the consensus recommendations for this report. After an iterative process of revisions, the final manuscript was presented to each of the respective societies for endorsement. Societies were asked to facilitate dissemination of the findings to their membership through presentations in society conferences and publication of summary reports in society journals, Web sites, and other forms of communication.

Results

1. Proposal for uniform standards for definition and classification of AKI

Definition and diagnostic criteria of AKI

For any condition, the clinician needs to know whether the disease is present and, if so, where and when the patient falls in the natural history of the disease. The former facilitates recognition whereas the latter defines time points for intervention. Unfortunately, there has been no uniformly accepted definition of AKI. Studies describe ARF or AKI based on serum creatinine changes, absolute levels of serum creatinine, changes in blood urea nitrogen or urine output, or the need for dialysis [1, 11, 20, 29–36]. The wide variation in definitions has made it difficult to compare information across studies and populations [37].

Diagnostic criteria

Recognition of AKI requires the delineation of easily measured criteria that can be widely applied. Serum creatinine levels and changes in urine output are the most commonly applied measures of renal function; however, they are each influenced by factors other than the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and do not provide any information about the nature or site of kidney injury. The proposed diagnostic criteria (Table 1) were based on consideration of the following concepts:

1. The definition needs to be broad enough to accommodate variations in clinical presentation over age groups, locations, and clinical situations.

2. Sensitive and specific markers for kidney injury are not currently available in clinical practice. Several groups are working on developing and validating biomarkers of kidney injury and GFR which may be used in the future for diagnosis and prognosis.

3. There is accumulating evidence that small increments in serum creatinine are associated, in a variety of settings, with adverse outcomes [13–20] that are manifest in short-term morbidity and mortality and in longer-term outcomes, including 1-year mortality [15–17]. Current clinical practice does not focus much attention on small increments in serum creatinine, which are often attributed to lab variations. However, the coefficient of variation of serum creatinine with modern analyzers is relatively small and therefore increments of 0.3 mg/dl (25 μmol/l) are unlikely to be due to assay variation [38]. Changes in volume status can influence serum creatinine levels [39]. Because the amount of fluid resuscitation depends on the underlying clinical situation [40], the group agreed that application of the diagnostic criteria would be used only after an optimal state of hydration had been achieved.

4. A time constraint of 48 hours for diagnosis was selected based on the evidence that adverse outcomes with small changes in creatinine were observed when the creatinine elevation occurred within 24 to 48 hours [15, 16] and to ensure that the process was acute and representative of events within a clinically relevant time period. In the two aforementioned studies, there was no distinction of underlying CKD or de novo AKI. However, in the study by Chertow and colleagues [13], the odds ratio for mortality with a change in creatinine of 0.3 mg/dl (25 μmol/l) was 4.1 (confidence interval 3.1 to 5.5) adjusting for CKD. There is no requirement to wait 48 hours to diagnose AKI or initiate appropriate measures to treat AKI. Instead, the time period is designed to eliminate situations in which the increase in serum creatinine by 0.3 is very slow and thus is not 'acute.'

5. It was recognized that AKI is often superimposed on pre-existing CKD. Further validation will be required to determine whether the criterion of a creatinine elevation of 0.3 mg/dl (25 μmol/l) is applicable to these patients (that is, whether a creatinine increase of more than 0.3 mg/dl from an elevated baseline represents AKI and has the same risks as a creatinine increase from a normal baseline).

6. The need for including urine output as a diagnostic criterion is based on the knowledge of critically ill patients in whom this parameter often heralds renal dysfunction before serum creatinine increases.

A minority of group members, both intensivists and nephrologists, felt that a urine output reduction of less than 0.5 ml/kg per hour over the span of six hours was not specific enough to lead confidently to the designation of AKI. It was recognized that the hydration state, use of diuretics, and presence of obstruction could influence the urine volume, hence the need to consider the clinical context. Additionally, accurate measurements of urine output may not be easily available in all cases, particularly in patients in non-intensive care unit settings. Despite these limitations, it was felt that the use of changes in urine offers a sensitive and easily discernible means of identifying patients, but its value as an independent criterion for diagnosis of AKI will need to be validated.

The proposed diagnostic criteria for AKI are designed to facilitate acquisition of new knowledge and validate the emerging concept that small alterations in kidney function may contribute to adverse outcomes. The goal of adopting these explicit diagnostic criteria is to increase the clinical awareness and diagnosis of AKI. It is recognized that there may be an increase in false-positives, so that some patients labeled with AKI will not have the condition. There was consensus that adopting the more inclusive criteria is preferable to the current situation, in which the condition is under-recognized and many people are identified late in the course of their illness and potentially miss the opportunity for prevention or application of strategies to minimize further kidney damage.

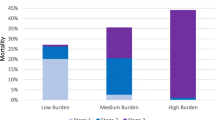

Staging/classification

The goal of a staging system is to classify the course of a disease in a reproducible manner that supports accurate identification and prognostication and informs diagnostic or therapeutic interventions. The group recognized that a number of systems for staging and classifying AKI are currently in use or have been proposed [41]. The RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease) criteria [25] proposed by the ADQI group were developed by an interdisciplinary, international consensus process and are now being validated by different groups worldwide [36, 37]. However, according to data that have emerged since then, smaller changes in serum creatinine than those considered in the RIFLE criteria might be associated with adverse outcomes [13–18]. Additionally, given the consensus definition for AKI (Table 1), RIFLE criteria have been modified so that patients meeting the definition for AKI could be staged (Table 2). The proposed staging system retains the emphasis on changes in serum creatinine and urine output but includes the following principles:

1. Although diagnosis of AKI is based on changes over the course of 48 hours, staging occurs over a slightly longer time frame. One week was proposed by the ADQI group in the original RIFLE criteria [25].

2. There was a conscious decision not to include the therapy for AKI (that is, renal replacement therapy [RRT]) as a distinct stage because this constitutes an outcome of AKI.

3. The new staging system maps to the RIFLE stages as follows:

3a. RIFLE 'Risk' category should have the same criteria as for the diagnosis of stage 1 AKI.

3b. Those who are classified as having 'Injury' and 'Failure' categories map to stages 2 and 3 of AKI.

3c. The 'Loss' and 'End-stage kidney disease' categories were removed from the staging system and remain outcomes.

3d. Given the variability inherent in commencing RRT and due to variability in resources in different populations and countries, patients receiving RRT are to be included in stage 3 (analogous to stage 5 CKD, GFR of less than 15, or dialysis).

2. Future joint conference topics and key collaborative research questions

There is a need to ensure that collaborative and integrated joint conferences are planned to facilitate the dissemination of knowledge, clarify clinical practice, and enhance research. Many organizations are currently in the process of planning meetings on ARF/AKI. These meeting take various forms: knowledge exchange/scientific meetings, consensus controversies, and research initiatives. The group described five key topics that should be addressed by any of the professional communities involved in the care of patients with AKI. The particular venue and the process and products of these conferences were not discussed in detail. An overview of the topics and issues that would be well served by a multidisciplinary consensus or controversies conference is presented in Table 3. These topics reflect important areas in which there is a need for ongoing research to develop evidence. A key step for future conferences will be to determine which research questions are most important and pressing to advance the field and improve outcomes from AKI.

3. Need for an international collaborative network

AKI is a global problem with varying etiologies and manifestations, but the outcomes are similar [1–4, 6]. Given the wide global variation in the natural history and management of AKI, it is essential that mechanisms for sharing information and for collaboration among centers be developed. It was felt that the establishment of an international collaborative research effort for AKI would contribute to international research and education about AKI. The group proposed four major topics that would need to be addressed by this initiative (Table 4).

Conclusion

AKI is a complex disorder for which there is no currently accepted uniform definition. Having a standard for diagnosing and classifying AKI would enhance our ability to improve the management of these patients. We have described the formation of a multidisciplinary collaborative network focused on AKI and have proposed uniform standards for diagnosing and classifying AKI. The proposed standards will need to be validated in future studies. These standards build upon existing knowledge and permit individuals using current staging systems (for example, RIFLE) to transition to the new system without loss of comparability. These recommendations have been endorsed by the participating societies, which represent the majority of the critical care and nephrology societies worldwide and which have been asked to disseminate the results via presentations at the national and regional society conferences and through publication of summary reports in society journals (see Table 5 for society endorsement details). We believe that these recommendations provide a stepping stone to standardizing the care of patients with AKI and will greatly enhance our ability to design prospective studies to evaluate potential prevention and treatment strategies. One of the limitations of consensus recommendations is that they are often not adopted. We anticipate that the broad support and commitment obtained through society involvement will significantly enhance the ability to disseminate the results to the worldwide community and to address this limitation. Future clinical and translational research in AKI will require the development of collaborative networks of investigators drawn from various disciplines to facilitate the acquisition of evidence through well-designed and well-conducted clinical trials, dissemination of information via multidisciplinary joint conferences and publications, and improvement of the translation of knowledge from pre-clinical research. We anticipate that the AKIN will provide an effective mechanism for facilitating efforts to improve patient outcomes.

Key messages

-

AKI is a complex disorder, and we have proposed uniform standards for diagnosing and classifying AKI on the basis of existing systems (that is, RIFLE). These proposals will require validation.

-

Our recommendations have been endorsed by participating societies that represent the majority of critical care and nephrology societies worldwide.

-

These recommendations provide a stepping stone to standardizing the care of patients with AKI and will greatly enhance our ability to design prospective studies to evaluate potential prevention and treatment strategies.

-

Future clinical and translational research in AKI will require the development of collaborative networks. The AKIN was formed to provide an effective mechanism for facilitating such efforts.

Abbreviations

- ADQI:

-

Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative

- AKI:

-

acute kidney injury

- AKIN:

-

Acute Kidney Injury Network

- ARF:

-

acute renal failure

- ASN:

-

American Society of Nephrology

- CKD:

-

chronic kidney disease

- GFR:

-

glomerular filtration rate

- ISN:

-

International Society of Nephrology

- NKF:

-

National Kidney Foundation

- RIFLE:

-

Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, and End-stage kidney disease

- RRT:

-

renal replacement therapy.

References

Mehta RL, Pascual MT, Soroko S, Savage BR, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Paganini EP, Chertow GM: Spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit: the PICARD experience. Kidney Int 2004, 66: 1613-1621. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00927.x

Palevsky PM: Epidemiology of acute renal failure: the tip of the iceberg. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 1: 6-7. 10.2215/CJN.01521005

Ympa YP, Sakr Y, Reinhart K, Vincent JL: Has mortality from acute renal failure decreased? A systematic review of the literature. Am J Med 2005, 118: 827-832. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.069

Metnitz PG, Krenn CG, Steltzer H, Lang T, Ploder J, Lenz K, Le Gall JR, Druml W: Effect of acute renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy on outcome in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2002, 30: 2051-2058. 10.1097/00003246-200209000-00016

Waikar SS, Curhan GC, Wald R, McCarthy EP, Chertow GM: Declining mortality in patients with acute renal failure, 1988 to 2002. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 17: 1143-1150. 10.1681/ASN.2005091017

Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, Doig GS, Morimatsu H, Morgera S, Schetz M, Tan I, Bouman C, Macedo E, et al.: Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA 2005, 294: 813-818. 10.1001/jama.294.7.813

Liangos O, Wald R, O'Bell JW, Price L, Pereira BJ, Jaber BL: Epidemiology and outcomes of acute renal failure in hospitalized patients: a national survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006, 1: 43-51. 10.2215/CJN.00220605

Clermont G, Acker CG, Angus DC, Sirio CA, Pinsky MR, Johnson JP: Renal failure in the ICU: comparison of the impact of acute renal failure and end-stage renal disease on ICU outcomes. Kidney Int 2002, 62: 986-996. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00509.x

Thakar CV, Worley S, Arrigain S, Yared JP, Paganini EP: Influence of renal dysfunction on mortality after cardiac surgery: modifying effect of preoperative renal function. Kidney Int 2005, 67: 1112-1119. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00177.x

Druml W: Long term prognosis of patients with acute renal failure: is intensive care worth it? Intensive Care Med 2005, 31: 1145-1147. 10.1007/s00134-005-2682-5

Liano F, Junco E, Pascual J, Madero R, Verde E: The spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit compared with that seen in other settings. The Madrid Acute Renal Failure Study Group. Kidney Int Suppl 1998, 66: S16-24.

Mehta RL, Pascual MT, Soroko S, Chertow GM: Diuretics, mortality, and nonrecovery of renal function in acute renal failure. JAMA 2002, 288: 2547-2553. 10.1001/jama.288.20.2547

Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW: Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005, 16: 3365-3370. 10.1681/ASN.2004090740

Gruberg L, Mintz GS, Mehran R, Gangas G, Lansky AJ, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Leon MB: The prognostic implications of further renal function deterioration within 48 h of interventional coronary procedures in patients with pre-existent chronic renal insufficiency. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000, 36: 1542-1548. 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00917-7

Lassnigg A, Schmidlin D, Mouhieddine M, Bachmann LM, Druml W, Bauer P, Hiesmayr M: Minimal changes of serum creatinine predict prognosis in patients after cardiothoracic surgery: a prospective cohort study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004, 15: 1597-1605. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000130340.93930.DD

Levy MM, Macias WL, Vincent JL, Russell JA, Silva E, Trzaskoma B, Williams MD: Early changes in organ function predict eventual survival in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med 2005, 33: 2194-2201. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000182798.39709.84

McCullough PA, Soman SS: Contrast-induced nephropathy. Crit Care Clin 2005, 21: 261-280. 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.12.003

Praught ML, Shlipak MG: Are small changes in serum creatinine an important risk factor? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2005, 14: 265-270.

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P: Acute renal failure – definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care 2004, 8: R204-212. 10.1186/cc2872

Hoste EAJ, Clermont G, Kersten A, Venkataraman R, Angus DC, De Bacquer D, Kellum JA: RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury is associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care 2006, 10: R73-82. 10.1186/cc4915

Palevsky PM, Metnitz PG, Piccinni P, Vinsonneau C: Selection of endpoints for clinical trials of acute renal failure in critically ill patients. Curr Opin Crit Care 2002, 8: 515-518. 10.1097/00075198-200212000-00006

Kellum JA, Leblanc M, Gibney RT, Tumlin J, Lieberthal W, Ronco C: Primary prevention of acute renal failure in the critically ill. Curr Opin Crit Care 2005, 11: 537-541. 10.1097/01.ccx.0000179934.76152.02

Kellum JA, Ronco C, Mehta R, Bellomo R: Consensus development in acute renal failure: The Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative. Curr Opin Crit Care 2005, 11: 527-532. 10.1097/01.ccx.0000179935.14271.22

Leblanc M, Kellum JA, Gibney RT, Lieberthal W, Tumlin J, Mehta R: Risk factors for acute renal failure: inherent and modifiable risks. Curr Opin Crit Care 2005, 11: 533-536. 10.1097/01.ccx.0000183666.54717.3d

Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Angus DC, Palevsky P, Ronco C: The first international consensus conference on continuous renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int 2002, 62: 1855-1863. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00613.x

American Society of Nephrology Renal Research Report J Am Soc Nephrol 2005, 16: 1886-1903. 10.1681/ASN.2005030285

Eknoyan G, Lameire N, Barsoum R, Eckardt KU, Levin A, Levin N, Locatelli F, MacLeod A, Vanholder R, Walker R, et al.: The burden of kidney disease: improving global outcomes. Kidney Int 2004, 66: 1310-1314. 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00894.x

Thompson BT, Cox PN, Antonelli M, Carlet JM, Cassell J, Hill NS, Hinds CJ, Pimentel JM, Reinhart K, Thijs LG: Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU: statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003: executive summary. Crit Care Med 2004, 32: 1781-1784. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000126895.66850.14

Lameire N, Van Biesen W, Vanholder R: Acute renal failure. Lancet 2005, 365: 417-430.

Brivet FG, Kleinknecht DJ, Loirat P, Landais PJ: Acute renal failure in intensive care units – causes, outcome, and prognostic factors of hospital mortality; a prospective, multicenter study. French Study Group on Acute Renal Failure. Crit Care Med 1996, 24: 192-198. 10.1097/00003246-199602000-00003

Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Christiansen CL, Cook EF, Hammermeister KE, Grover F, Daley J: Preoperative renal risk stratification. Circulation 1997, 95: 878-884.

Mehta RL, McDonald B, Gabbai F, Pahl M, Farkas A, Pascual MT, Zhuang S, Kaplan RM, Chertow GM: Nephrology consultation in acute renal failure: does timing matter? Am J Med 2002, 113: 456-461. 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01230-5

Mehta RL, Pascual MT, Gruta CG, Zhuang S, Chertow GM: Refining predictive models in critically ill patients with acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002, 13: 1350-1357. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000014692.19351.52

Vincent JL: Incidence of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit. Contrib Nephrol 2001, (132):1-6.

Hoste EA, Lameire NH, Vanholder RC, Benoit DD, Decruyenaere JM, Colardyn FA: Acute renal failure in patients with sepsis in a surgical ICU: predictive factors, incidence, comorbidity, and outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol 2003, 14: 1022-1030. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000059863.48590.E9

Uchino S, Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Bates S, Ronco C: An assessment of the RIFLE criteria for acute renal failure in hospitalized patients. Crit Care Med 2006, 34: 1913-1917. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000224227.70642.4F

Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C: Defining acute renal failure: physiological principles. Intensive Care Med 2004, 30: 33-37. 10.1007/s00134-003-2078-3

Perrone RD, Madias NE, Levey AS: Serum creatinine as an index of renal function: new insights into old concepts. Clin Chem 1992, 38: 1933-1953.

Moran SM, Myers BD: Course of acute renal failure studied by a model of creatinine kinetics. Kidney Int 1985, 27: 928-937.

Rivers EP: Early goal-directed therapy in severe sepsis and septic shock: converting science to reality. Chest 2006, 129: 217-218. 10.1378/chest.129.2.217

Mehta RL, Chertow GM: Acute renal failure definitions and classification: time for change? J Am Soc Nephrol 2003, 14: 2178-2187. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000079042.13465.1A

Acknowledgements

We would like to recognize the financial support provided by the ASN, ISN, and NKF for the AKIN conference. We are grateful for the logistical support provided by the NKF and the special efforts of Sue Levey for the meeting arrangements. Members from participating societies were supported by their respective societies (see Table 5).

Society and organization endorsements

Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative

Nephrology

American Society of Nephrology, American Society of Pediatric Nephrologists, Asian Pacific Society of nephrology, Chinese Society of Nephrology, European Dialysis and Transplant Association-European Renal Association, Indian Society of Nephrology, International Pediatric Nephrology Association, International Society of Nephrology, National Kidney Foundation, and Sociedade Latino-Americana de Nefrologia e Hipertensão.

Critical care

American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Asia Pacific Association of Critical Care Medicine, Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, Société de Réanimation de Langue Française, and Society of Critical Care Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

All authors participated in the AKIN conference workgroups, development of the summary statement, and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta, R.L., Kellum, J.A., Shah, S.V. et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 11, R31 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/cc5713

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/cc5713