Abstract

The transparency organization MapLight records instances of organizations taking positions for and against legislation in Congress. The dataset comprises some 130,000 such positions taken on thousands of bills between the 109th and 115th Congresses (2005–2018). The depth and breadth of these data potentially give them wide applicability for answering questions about interest group behavior and influence as well as legislative politics more broadly. However, the coverage and content of the data are affected by aspects of MapLight’s research process. This article introduces the MapLight dataset and its potential uses, examines issues related to sampling and other aspects of MapLight’s research process, and explains how scholars can address these to make appropriate use of the data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In our analysis, some groups with identical names appear to be associated with more than MLid. This may result from idiosyncrasies in naming conventions used by MapLight’s records, and the Center for Responsive Politics (CRP) conventions on which they are built, particularly as they track organizations’ formation, merging, acquisition, and dissolution. In a future release of the data, we plan to resolve these errors.

https://www.opensecrets.org/industries/slist.php, accessed 21 October 2019.

Volden and Wiseman (2014) differentiate between commemorative bills, substantive bills, and “substantive and significant” bills. The latter category is measured as the bill having received a write-up in an end-of-year Congressional Quarterly Almanac or, for more recent Congresses, the Congressional Quarterly Weekly/CQ Magazine during the Congress in which it was introduced. While we do not require this distinction to demonstrate MapLight’s preference for researching non-commemorative bills, it may prove useful for scholars working with MapLight data to leverage this more granular measure of legislative significance.

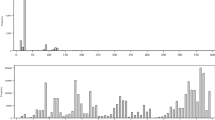

Readers with knowledge of congressional bill formatting may be aware that this is somewhat atypical of how Congress itself abbreviates bill types. In the MapLight data, and thus by implication in Fig. 4, “H” is used for House Bills (typically abbreviated “H.R.”), while “HR” is used for House Resolutions (typically abbreviated “H.Res.”).

Assuming a unidimensional spatial model of group preferences and that a subsequent version of a bill did not change which side of the status quo that bill fell upon, the organizations for whom such an assumption would not hold would be those who were close to indifferent between the original bill and the status quo it amended.

For example, before it became the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), 111 H.R. 3590 passed the House as the “Service Members Home Ownership Tax Act of 2009”, which amended the tax code to facilitate home ownership by military families.

While we have not used the California data and thus cannot speak to its usefulness for applied research, we note that California’s lobbying disclosure laws appear to require even less specificity about the issues and bills lobbied than does the federal LDA. Thus, MapLight’s California dataset may have fewer available substitutes than does the federal dataset that has been our focus here. In light of this possibility, we look forward to future assessments of the California dataset’s validity and reliability.

References

Anzia, Sarah F. 2019. Looking for influence in all the wrong places: How studying subnational policy can revive research on interest groups. The Journal of Politics 81(1): 343–351.

Baumgartner, Frank R., and Beth L. Leech. 2001. Interest niches and policy bandwagons: Patterns of interest group involvement in national politics. The Journal of Politics 63(4): 1191–1213.

Baumgartner, Frank R., Jeffrey M. Berry, Marie Hojnacki, Beth L. Leech, and David C. Kimball. 2009. Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bertrand, Marianne, Matilde Bombardini, and Francesco Trebbi. 2011. Is it whom you know or what you know? Technical report National Bureau of Economic Research: An empirical assessment of the lobbying process.

Box-Steffensmeier, Janet M., Dino P. Christenson, and Matthew P. Hitt. 2013. Quality over quantity: Amici influence and judicial decision making. American Political Science Review 107(3): 446–460.

Broz, J. Lawrence. 2016. “China, Currency Misalignments, and Industry Demands for Trade Protection in the United States.” working paper . Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2490648.

Crosson, Jesse M., Alexander C. Furnas and Geoffrey M. Lorenz. 2019. “Estimating proposal and status quo locations for legislation using cosponsorships, roll-call votes, and interest group bill positions. Presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Political Methodology (POLMETH), Boston, MA, July 18–20, 2019.

Crosson, Jesse M., Alexander C. Furnas and Geoffrey M. Lorenz. 2019. “Polarized pluralism: Organizational preferences and biases in the American pressure system”. American Political Science Review. accepted.

Dwidar, Maraam A. 2019. “Diverse lobbying coalitions and influence in notice-and-comment rulemaking”. working paper.

Fagan, E. J., Zachary A. McGee and Herschel F. Thomas. 2019. “The power of the party: Conflict expansion and the agenda diversity of interest groups.” Political Research Quarterly. accepted.

Furnas, Alexander C., Michael T. Heaney, and Timothy M. LaPira. 2019. The partisan ties of lobbying firms. Research & Politics 6(3): 1–9.

Galantucci, Robert A. 2015. The repercussions of realignment: United States-China interdependence and exchange rate politics. International Studies Quarterly 59(3): 423–435.

Garlick, Alexander Russell. 2016. “Interest groups, lobbying and polarization in the United States”, PhD thesis , University of Pennsylvania. 2298. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2298

Grossmann, Matt, and Kurt Pyle. 2013. Lobbying and congressional bill advancement. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2(1): 91–111.

Holyoke, Thomas T. 2019. Strategic lobbying to support or oppose legislation in the U.S. congress. Journal of Legislative Studies 25(4): 533–552.

Junk, Wiebke Marie. 2019. When diversity works: The effects of coalition composition on the success of lobbying coalitions. American Journal of Political Science 63(3): 660–674.

Kim, In Song. 2017. Political cleavages within industry: Firm-level lobbying for trade liberalization. American Political Science Review 111(1): 1–20.

Kim, In Song. 2018. “LobbyView: Firm-level lobbying & congressional bills database.” Working Paper available from http://web.mit.edu/insong/www/pdf/lobbyview.pdf.

King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

LaPira, Timothy M., and Herschel F. Thomas. 2017. Revolving door lobbying: Public service, private influence, and the unequal representation of interests. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Lorenz, Geoffrey Miles. 2020. Prioritized interests: Diverse lobbying coalitions and congressional committee agenda setting. The Journal of Politics 82(1): 225–240.

McKay, Amy. 2012. Negative lobbying and policy outcomes. American Politics Research 40(1): 116–146.

Moore, Ryan T., Eleanor Neff Powell, and Andrew Reeves. 2013. Driving support: Workers, PACs, and congressional support of the auto industry. Business and Politics 15(2): 137–162.

Osgood, Iain. 2017. The breakdown of industrial opposition to trade: Firms, product variety, and reciprocal liberalization. World Politics 69(1): 184–231.

Thieme, Sebastian. 2019. “Moderation or Strategy? Political Giving by Corporations and Trade Groups.” Journal of Politics . forthcoming.

Vidal, Jordi Blanes I., Mirko Draca, and Christian Fons-Rosen. 2012. Revolving door lobbyists. The American Economic Review 102(7): 3731–3748.

Volden, Craig, and Alan E. Wiseman. 2014. Legislative effectiveness in the United States congress: The lawmakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

You, Hye Young. 2017. Ex post lobbying. The Journal of Politics 79(4): 1162–1176.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenz, G.M., Furnas, A.C. & Crosson, J.M. Large-N bill positions data from MapLight.org: What can we learn from interest groups’ publicly observable legislative positions?. Int Groups Adv 9, 342–360 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-020-00085-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-020-00085-x