Abstract

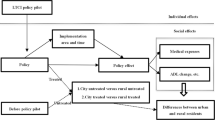

To achieve a tiered healthcare system in China, the government has beefed up efforts to encourage people to embrace private health insurance. One of the steps is to introduce tax-subsidized health insurance (TSHI) in 2015. This paper assesses whether TSHI is successful in improving health and easing financial burden. Using unique data from the Domestic TSHI Consumers Evaluation Survey in 2019 and Propensity Score Matching method, we find that TSHI has been effective in improving participants’ health status, but not in lowering out-of-pocket (OOP) burden. Besides, TSHI can increase the utilization of both inpatient and outpatient care, which provides a possible explanation for beneficial health effect. From an internal perspective, TSHI has the potential to reduce disparities in health and access to healthcare services. Our results provide implications on modifying the benefit design of TSHI to better complement basic medical insurance system and on reforming the current tax incentive policy to reach out a large number of low-income people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to the released data from China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, the annual average growth rate for premium is 28.54% from 2009 to 2019.

In 2019, the total premiums of private health insurance in China were 706.6 billion yuan, and the population and GDP were 1.41 billion and 98.65 trillion, respectively.

During 1989 and 1990, RAND Corporation conducted another randomized experiment in more than 20 villages in China, hence namely “China Rural Health Insurance Experiment,” and they reached a similar conclusion that providing health insurance could increase per capita expenditure for health care, especially outpatient expenditures (Cretin et al. 2007).

More detailed description and summary can be found in “Literature Review” section.

For more related studies, please refer to “Appendix 1”.

Data source: National Healthcare Security Development Report 2019. Available online (in Chinese): http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/6/24/art_7_3268.html.

Data source: National Healthcare Security Development Report 2019. Available online (in Chinese): http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/6/24/art_7_3268.html.

Data source: The URRBMI financial subsidy standard is not less than 580 yuan per person per year. Available online (in Chinese): http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2021-06/10/content_5616558.htm.

Data source: National Healthcare Security Development Report 2019. Available online (in Chinese): http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2020/6/24/art_7_3268.html.

In 2019, the out-of-pocket expenses accounted for 28.36% of total healthcare costs in China. Data source: National Healthcare System Development Report 2019. Available online (in Chinese): http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-04/09/content_5598657.htm.

Data source: Weaving a Safety Net for Public Health—Research on the Complementation of Commercial Health Insurance and Basic Medical Insurance, China Development Research Foundation, Beijing: China Development Press, 2019.

For private health insurances in other countries, we choose (1) Germany: People with PHI can claim their contributions as tax-deductible expenses in the annual income tax return; (2) Brazil: Private health insurance takes a supplementary role in health coverage; tax incentives are available for those who purchase health insurance; insurers must renew contracts or provide an equivalent substitute, and cannot reject applications based on age or health status, or exclude pre-existing conditions for individual, family or non-sponsored group contracts with fewer than 50 members; (3) Egypt/India: People are encouraged to take-up private health insurance through tax subsidies, and private health insurance penetration levels are low in these two countries; (4) Canada: Both the federal government and all provincial government allow firms to deduct the cost of health benefits from employee’s taxable income.

The official data for TSHI participation and policyholders’ evaluation in 2019 is not available for this study, and all information comes from the survey data. Readers with interests in official data may contact the corresponding author, and the data will be provided as soon as it becomes available.

A detailed description about the change of sample sizes can be found in “Appendix 3.”

The current basic medical insurance system in China consists of two main schemes, the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI), which provides medical insurance to formal-sector urban employees and retirees, and the Urban and Rural Resident Basic Medical Insurance (URRBMI), which covers unemployed urban residents, the self-employed, employees in informal sectors and rural residents. A very small percentage of the population is covered by Free Basic Medical Insurance (FBMI).

We use tier-1 cities to study regional heterogeneous impact for robustness check in Sect. 7.

After consulting several insurance companies and groups that offered TSHI to their employees, we have observed a so-called herd effect that some employees tend to follow others’ purchase decisions and ignore their own private information, which might also help us understand the insignificant effects of some characteristics.

This could be explained by the fact that the college students learn to invest in assets that could produce long-term returns (including health), or that well-educated people have better compliance with doctor's advice.

WHO (1963) lists young adulthood from 18 to 45, middle age from 45 to 59, and old age from above 60.

The region information is collected from the survey question 7 which asks respondents “Which province do you currently live in?” Although Shenzhen and Guangzhou are not either province or municipality, they are both located in Guangdong province, which is the largest GDP contributor on the provincial level for the last five years (2015–2019) and considered one of the most prosperous provinces in China. Thus, if respondents are from Guangdong province, we also treat them as living in tier-1 cities.

Tables for Robustness Tests and Discussion (Tables 11–18) can be found in “Appendix 4.”

The average OOP burden of matched non-participants in our sample is 0.2837. In the survey data, healthcare utilization, including number of outpatient visits, outpatient charges, length of stay and inpatient charges, and OOP burden are interval censored, and we only know the ordered category into which each observation falls but not the exact value of the observation. In our study, we choose the midpoint of an interval and the lower boundary of the highest interval as a proxy to calculate the average OOP burden. It is the same for healthcare utilization.

References

Bagnoli, L. 2019. Does Health Insurance Improve health for all? Heterogeneous effects on children in Ghana. World Development 124: 1–16.

Baicker, K., S.L. Taubman, H.L. Allen, M. Bernstein, J.H. Gruber, J.P. Newhouse, E.C. Schneider, B.J. Wright, A.M. Zaslavsky, A.N. Finkelstein; Oregon Health Study Group. 2013. The Oregon Experiment—Effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. The New England Journal of Medicine 368 (18): 1713–1722.

Bhattacharya J., Timothy, H, and T. Peter. 2014. Health economics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Card, D., C. Dobkin, and N. Maestas. 2009. Does Medicare save lives? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124 (2): 597–636.

Chen, Y., and G. Jin. 2012. Does health insurance coverage lead to better health and educational outcomes? Evidence from rural China. Journal of Health Economics 31: 1–14.

Cheng, L., H. Liu, Y. Zhang, K. Shen, and Y. Zeng. 2015. The impact of health insurance on health outcomes and spending of the elderly: Evidence from China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme. Health Economics 24: 672–691.

Cheung, D., J.P. Laffargue, and Y. Padieu. 2016. Insurance of household risks and the rebalancing of the Chinese economy: Health insurance, health expenses and household savings. Pacific Economic Review 21: 381–412.

Cretin, S., A.P. Williams, and J. Sine. 2007. China rural health insurance experiment: Final Report. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Currie, J., and J. Gruber. 1996a. Health insurance eligibility, utilization of medical care, and child health. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111: 431–466.

Currie, J., and J. Gruber. 1996b. Saving babies: The efficacy and cost of recent changes in the Medicaid eligibility of pregnant women. Journal of Political Economy 104: 1263–1296.

Currie, J., S. Decker, and W. Lin. 2008. Has public health insurance for older children reduced disparities in access to care and health outcomes? Journal of Health Economics 27: 1567–1581.

Doyle, J.J. 2005. Health insurance, treatment and outcomes: Using auto accidents as health shocks. Review of Economics and Statistics 87 (2): 256–270.

Engelhardt, G.V., and J. Gruber. 2011. Medicare Part D and the financial protection of the elderly. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 3 (4): 77–102.

Fan, H., S. Liu, and L. Chen. 2019. Does commercial health insurance enhance public health? An empirical analysis based on Chinese micro-data. Insurance Studies 3: 116–127.

Feldstein, M., and J. Gruber. 1995. A major risk approach to health insurance reform. Tax Policy and the Economy 9: 103–130.

Fihn, S.D., and J.B. Wicher. 1988. Withdrawing routine outpatient medical services: Effects on access and health. Journal of General Internal Medicine 3: 356–362.

Finkelstein, A., and R. McKnight. 2008. What did Medicare do? The initial impact of Medicare on mortality and out of pocket medical spending. Journal of Public Economics 92: 1644–1668.

Finkelstein, A., S. Tambman, B. Wright, M. Bernstein, J. Gruber, H. Allen, and K. Baicker. 2012. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the first year. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 127 (3): 1057–1106.

Goldman, D.P., J. Bhattacharya, D.F. McCaffrey, N. Duan, A.A. Leibowitz, G.F. Joyce, and S.C. Morton. 2001. Effect of insurance on mortality in an HIV-positive population in care. Journal of the American Statistical Association 96 (455): 883–894.

Goodman-Bacon, A. 2018. Public insurance and mortality: Evidence from Medicaid implementation. Journal of Political Economy 126 (1): 216–262.

Grignon, M., M. Perronnin, and J.N. Lavis. 2008. Does free complementary health insurance help the poor to access health care? Evidence from France. Health Economics 17 (2): 203–219.

Grossman, M. 1972. On the concept of health capital and the demand for health. The Journal of Political Economy 80 (2): 223–255.

Guan, J., and J. Tena. 2018. Do social medical insurance schemes improve children's health in China? Working Paper CRENoS, No. 2018-07.

Hanratty, M.J. 1996. Canadian National Health Insurance and infant health. The American Economic Review 86 (1): 276–284.

He, H., and P.J. Nolen. 2019. The effect of health insurance reform: Evidence from China. China Economic Review 53: 168–179.

Hou, Z., E. Van de Poel, E. Van Doorslaer, B. Yu, and Q. Meng. 2014. Effects of NCMS coverage on access to care and financial protection in China. Health Economics 23: 917–934.

Huang, F., and L. Gan. 2010. Excess demand or appropriate demand? Health insurance, medical care and mortality of the elderly in urban China. Economic Research Journal 6: 105–119.

Hullegie, P., and T.J. Klein. 2010. The effect of private health insurance on medical care utilization and self-assessed health in Germany. Netspar Discussion Paper, No. 06/2010-023.

Hurley, J., and G. Emmanuel Guindon. 2020. Private health insurance in Canada. In Private health insurance: History, politics and performance (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies), ed. J. North (Author), S. Thomson, A. Sagan, and E. Mossialos, 99–141. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keeler, E., J.L. Buchanan, J.E. Rolph, J.M. Hanley, and D.M. Reboussin. 1998. The demand for episodes of medical treatment in the health insurance experiment. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Lei, X., and W. Lin. 2009. The New Cooperative Medical Scheme in rural China: Does more coverage mean more service and better health? Health Economics 18: S25–S46.

Lewbel, A. 2012. Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 30 (1): 67–80.

Li, Y., Q. Wu, C. Liu, Z. Kang, X. Xie, H. Yin, M. Jiao, G. Liu, Y. Hao, and N. Ning. 2014. Catastrophic health expenditure and rural household impoverishment in China: What role does the New Cooperative Health Insurance Scheme play? PLoS ONE 9 (4): e93253.

Lichtenberg, F. 2002. The effects of Medicare on health care utilization and outcomes. Forum for Health Economics and Policy 5 (1): 1028–1028.

Liu, H., and Z. Zhao. 2014. Does health insurance matter? Evidence from China’s urban resident basic medical insurance. Journal of Comparative Economics 42 (4): 1007–1020.

Montoya Diaz, M., N. Haber, P. Mladovsky, E. Pitchforth, W. Fayek Saleh, and F. Mori Sarti. 2020. Private health insurance in Brazil, Egypt and India. In Private health insurance: History, politics and performance (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies), ed. J. North (Author), S. Thomson, A. Sagan, and E. Mossialos, 65–98. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newhouse, J.P. 1993. Free for all? Evidence from the RAND health insurance experiment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Pan, J., X. Lei, and G. Liu. 2013. Does health insurance lead to better health? Economic Research Journal 4: 130–142+156.

Perry, C.W., and H.S. Rosen. 2004. The self-employed are less likely to have health insurance than wage earners. So what? In Entrepreneurship and public policy, vol. 3, ed. D. Holtz-Eakin and H.S. Rosen. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Shigeoka, H. 2014. The effect of patient cost sharing on utilization, health, and risk protection. American Economic Review 104 (7): 2152–2184.

Taubman, S.L., H.L. Allen, B.J. Wright, K. Baicker, and A.N. Finkelstein. 2014. Medicaid increases emergency-department use: Evidence from Oregon’s Health Insurance Experiment. Science 343 (6168): 263–268.

Wagstaff, A., and M. Lindelow. 2008. Can insurance increase financial risk? The curious case of health insurance in China. Journal of Health Economics 27 (4): 990–1005.

Wagstaff, A., L. Magnus, J. Gao, L. Xu, and J. Qian. 2009. Extending health insurance to the rural population: An impact evaluation of China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme. Journal of Health Economics 28: 1–19.

Wo, T., J. Liu, G. Li, and X. Xi. 2020. Factors influencing individuals’ take-up of tax-subsidized private health insurance: A cross-sectional study in China. Journal of Medical Economics 23 (7): 760–766.

Yi, B. 2021. Healthcare security system in China: An overview. Hepatobiliary Surgery and Nutrition 10 (1): 93–95.

Yip, W., and W. Hsiao. 2009. Non-evidence-based policy: How effective is China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme in reducing medical impoverishment? Social Science and Medicine 68: 201–209.

Zhang, C., X. Lei, J. Strauss, and Y. Zhao. 2017a. Health insurance and health care among the mid-aged and older Chinese: Evidence from The National Baseline Survey of CHARLS. Health Economics 26: 431–449.

Zhang, A., Z. Nikoloski, and E. Mossialos. 2017b. Does health insurance reduce out-of-pocket expenditure? Heterogeneity among China’s middle-aged and elderly. Social Science and Medicine 190: 11–19.

Zhou, Z., L. Zhu, Z. Zhou, Z. Li, J. Gao, and G. Chen. 2014. The effects of China’s urban basic medical insurance schemes on the equity of health service utilization: Evidence from Shaanxi Province. International Journal for Equity in Health 13: 23.

Zhou, M., S. Liu, M.K. Bundorf, K. Eggleston, and S. Zhou. 2017. Mortality in rural China declined as health insurance coverage increased, but no evidence the two are linked. Health Affairs 36 (9): 1672.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (JBK21YJ35). We thank Dr. Zhuxin Mao and Dr. Yinzhi Wang (Southwestern University of Finance and Economics) for providing helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of both authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Studies that estimate the impact of medical insurance on health outcomes, OOP burden, and utilization of medical care

Paper | Nation and program | Health outcomes | OOP burden | Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Feldstein and Gruber (1995) | USA, “major risk policy” approach | A health insurance plan that has a 50% co-insurance but limits OOP spending to 10% of income can substantially reduce total medical spending | ||

Keeler et al. (1988) | USA, RAND HIE | Cost sharing, including co-insurance and deductibles reduces use of medical services | ||

Newhouse (1993) | USA, RAND HIE | No significant effects on a wide range of measures of health status for the average patient, except for persons with poor vision or elevated blood pressure | Health insurance without co-insurance leads to more people using services and to more services per user, referring to both outpatient and inpatient service | |

Fihn and Wicher (1988) | USA, outpatient services at the Seattle VA Medical Center | Cancelation of VA health benefits associated with increase in blood pressure | ||

Perry and Rosen (2004) | USA, employer-based health insurance | No differences in self-reported health status or in the probability of a number of conditions between the self-employed and wage earners | ||

Doyle (2005) | USA, private health insurance | The uninsured have a substantially higher mortality rate | The uninsured receive 20% less care | |

Lichtenberg (2002) | USA, Medicare | Increases the survival rate of the elderly | Increases visits to physician’s offices and utilization of ambulatory and inpatient care | |

Card et al. (2009) | USA, Medicare | Decreases mortality of ED admission | Increases number of procedures and total list charges | |

Finkelstein and McKnight (2008) | USA, Medicare | Medicare has no impact on overall elderly mortality in its first 10 years | Substantially reduces the elderly’s OOP risk | |

Engelhardt and Gruber (2011) | USA, Medicare | The extension of Medicare Part D is associated with sizeable reductions in OOP spending | ||

Currie and Gruber (1996a) | USA, Medicaid | Medicaid eligibility significantly reduces children’s mortality | Significantly increases the utilization of medical care, particularly care delivered in physicians' offices | |

Currie and Gruber (1996b) | USA, Medicaid | Expanded eligibility for pregnant women lowers the incidence of infant mortality and low birth weight | ||

Goldman et al. (2001) | USA, Medicaid | Health insurance can have a dramatic effect on mortality among patients with HIV | ||

Currie et al (2008) | USA, Medicaid | Medicaid eligibility has little effect on children’s current health status, but eligibility in early childhood has positive effects on future health | Eligibility for older children improves current utilization of preventive care | |

Finkelstein et al. (2012) | USA, Medicaid | Extending access to Medicaid can improve self-reported physical and mental health | Medicaid lowers OOP medical expenditures and medical debt | Medicaid can induce higher healthcare utilization (including primary and preventive care as well as hospitalizations) |

Baicker et al. (2013) | USA, Medicaid | The 2008 Medicaid expansion in Oregon generates no significant improvements in measured physical health outcomes in the first 2 years, but raises rates of diabetes detection and management, and lowers rates of depression | Reduces financial strain | Increases use of healthcare services |

Taubman et al. (2014) | USA, Medicaid | The Medicaid expansion in Oregon increases overall emergency use by 0.41 visits per person, or 40% relative to an average of 1.02 visits per person in the control group | ||

Goodman-Bacon (2018) | USA, Medicaid | Medicaid’s introduction reduces mortality rates among nonwhite infants and children in the 1960s and 1970s | ||

Hanratty (1996) | Canada, National Health Insurance | Reduces infant mortality by 4% and low birth weight by 1.3% | ||

Lei and Lin (2009) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | No improvement in health status, measured by self-reported health status and by sickness or injury in the past 4 weeks | No reduction in OOP expenditure | Increases the utilization of preventive care, particularly general physical examinations |

Chen and Jin (2012) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | NCMS does not affect child morality and maternal mortality, but help improve the school enrollment of 6-year-olds | ||

Wagstaff et al. (2009) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | No reduction in overall OOP expenses, OOP expenses per outpatient visit or inpatient spell | Increases outpatient and inpatient utilization | |

Yip and Hsiao (2009) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | NCMS is not effective at addressing medical impoverishment, because it overlooks spending on chronic diseases | ||

Hou et al. (2014) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | NCMS does not increase financial protection | NCMS is effective in increasing access to care | |

Li et al. (2014) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | NCMS fails to prevent catastrophic health expenditure and medical impoverishment | ||

Cheng et al. (2015) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | NCMS improves the elderly enrollees’ activities of daily living and cognitive function, but does not lead to better self-assessed health status | There is no evidence that the NCMS has reduced their out-of-pocket spending | The elderly participants are more likely to get adequate medical services when sick |

Cheung et al. (2016) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | The NCMS induces an increase in OOP health expense for mild illness and a decrease in health payments for more serious illnesses; The NCMS also leads to a higher incidence of catastrophic healthcare spending | ||

Zhou et al. (2017) | China, New Cooperative Medical Scheme | There is little evidence that NCMS expansion contributes to mortality decline | ||

Pan et al. (2013) | China, Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance | URBMI has a positive effect on health | The insured do not pay more for the services | The insured receive more and better inpatient care |

Liu and Zhao (2014) | China, Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance | URBMI does not reduce total OOP health expenses | URBMI increases the utilization of formal medical services, especially for children, low-income families and residents in the poor region | |

China, three types of Basic Medical Insurance Schemes | NCMS membership is not significantly correlated with outpatient service utilization; access to three types of Basic Medical Insurance Schemes is positively related to inpatient service utilization | |||

China, three types of Basic Medical Insurance Schemes and other insurances | Health insurance reduces inpatient OOP expenditure; OOP spending on pharmaceuticals is reduced for inpatient care but not for outpatient care | Having health insurance increases the likelihood of utilizing healthcare | ||

Wagstaff and Lindelow (2008) | China, three types of health insurance schemes | China's government and labor insurance schemes increases financial risk associated with household healthcare spending, but rural cooperative medical scheme significantly reduces financial risk in some areas but increased it in others; China's new health insurance schemes have also increased the risk of high levels of OOP spending | ||

Guan and Tena (2018) | China, NCMS and URBMI | Social medical insurance schemes have no effect or even a marginally negative effect on children's health status in some cases | Participating in social medical insurance schemes significantly increases children's yearly hospital use, especially for children who come from rural China | |

Shigeoka (2014) | Japan, Elderly Health Insurance | Lower cost sharing does not improve health measures such as mortality and self-reported physical and mental health | Lower cost sharing yields reduction in OOP expenditure | Reduction in cost sharing increases healthcare utilization for both outpatient visits and inpatient admissions |

Grignon et al. (2008) | France, free complementary health insurance plan | The plan is lack of an overall effect on utilization | ||

Hullegie and Klein (2010) | Germany, private health insurance | Positive effects of private health insurance on health | Negative effects of private health insurance on the number of doctor visits, no effects on the number of nights spent in a hospital | |

Montoya Diaz et al. (2020) | Brazil/Egypt/India, private health insurance | PHI fails to address the problem of high OOP payments on health care in the three countries, because it is beyond the financial reach of those most in need of access to health care and financial protection | ||

Hurley and Emmanuel Guindon (2020) | Canada, private health insurance | Except for drug sector, where it covers a large number of people not covered by public insurance programs, PHI contributes in only a minor way to financial protection | People with private drug insurance tend to use more publicly financed physician services |

Appendix 2

Domestic TSHI Consumers Evaluation Survey Questionnaire

Part A Demographic Backgrounds

1. What is your age? ______ years old.

2. What is your gender?

A. Male B. Female

3. What is your marital status?

A.Unmarried B. Married C. Divorced D. Widowed

4. What is the highest degree or level of education you have completed?

A.Junior high school B. High school C. Bachelor's degree D. Master's degree or higher

5. Your after-tax monthly income is about ______ yuan.

6. What is your current employment status?

A. Work in state-owned enterprises

B. Work in public institutions

C. Work in private enterprises

D. Freelancers

E. Rural migrant workers

F. Agricultural workers

G. Unemployed

H. Retired

I. Other

7. Which province do you currently live in?

(1) Beijing (2) Tianjin (3) Hebei (4) Shanxi (5) Inner Mongolia (6) Liaoning

(7) Jilin (8) Heilongjiang (9) Shanghai (10) Jiangsu (11) Zhejiang (12) Anhui

(13) Fujian (14) Shandong (15) Henan (16) Hubei (17) Hunan (18) Jiangxi.

(19) Guangdong (20) Guangxi (21) Hainan (22) Chongqing (23) Sichuan (24) Guizhou

(25) Yunnan (26) Tibet (27) Shaanxi (28) Gansu (29) Qinghai (30) Ningxia

(31) Xinjiang

8. What is your area of residence?

A. Urban area B. Rural area

Part B Health Status and Medical Insurance

9. In general, how would you rate your current health status?

A. Poor B. Average C. Good D. Very Good

10. During the last 12 months, how many times did you visit a hospital, health center or clinic for outpatient care?

A. 0–5 times B. 6–10 times C. 11–20 times D. 21 times or more

11. What was the total cost of outpatient care for the last 12 months? (Includes out-of-pocket part and reimbursement part)

A. 0–500 yuan B. 501–1000 yuan C. 1001–2000 yuan D. 2001–5000 yuan

E. 5001 yuan or more

12. What was the reimbursement rate of basic medical insurance for the outpatient care?

A. 0–10% B. 11–20% C. 21–30% D. 31–40% E. 41–50% F. 51–60% G. 61–100%

H. 71–80% I. 81–90% J. 91–100%

13. During the last 12 months, how many days did you stay in a hospital to receive inpatient care?

A. 0–5 days B. 6–10 days C. 11–20 days D. 21–40 days E. 41 days or more

14. What was the total medical cost for all the inpatient care you received during the last 12 months? (Includes out-of-pocket part and reimbursement part)

A. 0–2 thousands B. 2–5 thousands C. 5–10 thousands D. 10–20 thousands

E. 20–50 thousands F. 50–100 thousands G. 100–200 thousands H. more than 200 thousands

15. What was the reimbursement rate of basic medical insurance for the inpatient care?

A. 0–10% B. 11–20% C. 21–30% D. 31–40% E. 41–50% F. 51–60% G. 61–100%

H. 71–80% I. 81–90% J. 91–100%

16. What was the percentage of your out-of-pocket medical expenses (including inpatient and outpatient care) during the last 12 months to the total household expenditure?

A. 0–20% B. 21–40% C. 41–60% D. 61–80% E. 81–100%

17. How often do you take a physical examination?

A. Once every 6 months B. Once a year

C. Once every 2 or 3 years D. Never took a physical examination in last 5 years

18. What is your basic medical insurance type?

A. Free medical insurance

B. Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance

C. Urban and Rural Residents Basic Medical Insurance

D. No basic medical insurance

19. Do you think the basic medical insurance can meet your healthcare needs?

A. Yes (Skip to q. 21) B. No (Skip to q. 20) C. Do not know (Skip to q. 21)

20. What is the main reason you think basic medical insurance cannot meet your needs?

A. Low reimbursement rate B. Restricted benefit list C. Hard to deal with critical illness

D. Other, please specify ______

21 . By which one of the following methods would you prefer to finance out-of-pocket medical expenses?

A. Engage in precautionary savings B. Borrow from friends or relatives

C. Purchase private health insurance coverage D. Other, please specify______

Part C Tax-subsidized Health Insurance

22. Do you know of Tax-subsidized health insurance, whose premium can be deducted before personal income tax, with a limit of 2400 yuan per year?

A. Yes (Skip to q. 23) B. No (Skip to q. 24)

23. Where did you learn about TSHI?

A. Promotional materials from insurance companies

B. Advices from insurance brokers

C. On TV, radio, newspapers and magazines

D. On the Internet, social media apps like WeChat or Weibo

E. At the workplace or community

F. Learn from families or friends

G. Other

24. Which of the following features of TSHI appeals to you? (Choose all that apply)

A. Premium is tax deductible, with a limit of 2400 yuan per year.

B. TSHI covers pre-existing diseases.

C. Besides medical payments coverage, TSHI provides individual accounts for investment, with the settlement interest rate to be at least 2.5%.

D. TSHI is a guaranteed renewal policy until the age of retirement.

E. TSHI has no deductibles or waiting period.

F. TSHI covers specified drugs, items, or medical materials not covered by basic medical insurance.

G. None of the above.

25. Do you have TSHI?

A. Yes (Skip to q. 26) B. No (Skip to q. 31)

26. Where did you buy TSHI?

A. Through employers

B. Through direct writers

C. Through brokers or agents

D. On the Internet, or mobile apps

E. Through telemarketing channels

F. Other

27. How much did you pay for TSHI?

A. 1–200 yuan B. 200–400 yuan C. 400–700 yuan D. 700–1000 yuan E. 1000–1500 yuan

F. 1500–2000 yuan G. 2000–3000 yuan H. 3000–4000 yuan I. 4000–5500 yuan

J. more than 5500 yuan

28. How would you like to rate the premium of TSHI?

A. The premium was higher than expected.

B. The premium was appropriate.

C. The premium was lower than expected.

D. Do not know.

29. What was the coverage limit of your TSHI?

A. 200 thousand yuan per year

B. 250 thousand yuan per year

C. 300 thousand yuan per year

D. Other, please specify ______

30. Would you like to renew your TSHI policy?

A. Yes B. No

31. Do you have any suggestions for the benefit design of TSHI? (Choose all that apply)

A. Raise the tax deduction limit of 2400 yuan per year, or set no limit.

B. Raise the coverage limit of 200–300 thousand yuan.

C. Enlarge the list of covered drugs, items, and medical materials that are not paid by basic medical insurance.

D. Streamline the tax deduction procedure of TSHI premium.

E. Other, please specify ______.

Appendix 3

Change of Sample Sizes

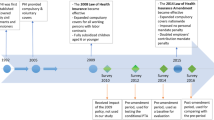

The questionnaires were delivered across the nation with the assistance of the Insurance Association of China in August 2019, and after 2 months, 15,885 questionnaires were returned by respondents in total.

Then data cleaning was performed in the following steps. First, the observations that took less than 60 s (5% quantile) to answer the questions were dropped from the sample. Then, our dataset was restricted to respondents from age 18 to 65, as TSHI is not available for children or the elderly. We further discarded observations with missing information on key variables such as after-tax monthly income and proportion of OOP medical expenses in total household expenditure. We then excluded respondents whose after-tax monthly income was beyond the quantile (1%, 99%). Our final sample consisted of 11,939 observations.

In PSM, we employed one-to-one nearest neighbor matching within a caliper distance of 0.01 to match each participant with a non-participant. Further, observations not in the common support area were dropped from the sample in order to satisfy the common support condition. Therefore, after matching only 2744 observations were kept in the sample.

Appendix 4

See Tables 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and 18.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, F., Wei, L. The impact of tax-subsidized health insurance on health and out-of-pocket burden in China. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 48, 194–246 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-022-00276-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-022-00276-4