Abstract

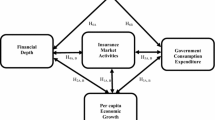

This study constructs a simple model to demonstrate that life insurance and financial development simultaneously affect economic growth. We provide empirical evidence on the model’s critical prediction. By analysing panel data for 17 advanced European countries from 1980 to 2015, the results show that the effect of private credit on real economic growth is negative in both the long and short run. The negative finance–growth nexus may be due to excessive financing in European countries. The financial crises that occurred during the study period may also have contributed to the negative effects. We find that an increase in the consumption of life insurance is a viable and long-term policy since life insurance penetration promotes long-term economic growth but is not obvious in the short term. Finally, life insurance development is a panacea in the finance–growth nexus since it not only helps moderate long-term real growth volatility but also absorbs the side effect of private credit on real economic growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some studies have investigated the impacts of stock or bond markets on economic development. However, these two sectors are direct finance and are not classified as financial intermediaries. Since the focus of this study is about financial intermediations, it is not appropriate to include the measurements of direct finance. In addition, Haiss and Sumegi (2008) mentioned that there is a certain overlap of businesses and assets between stock markets and financial intermediations. Therefore, including the stock market may lead to the risk of ‘double counting’, which might lead to biased results.

Although Arena (2008) and Lee (2013) used panel data in their study, the panel GMM estimator they used is not suitable for observing short-term effects. Loayza and Ranciere (2006) indicated that the GMM method based on time-series average data (e.g. over five-year intervals) can lead to loss of information and hide the potential dynamic finance–growth relationship.

We also compare another financial development indicator, bank credit, which is the ratio of the value of credits by deposit money banks, with private credit for our sample countries, and find that 15 of the 17 countries have their bank credit value equal to private credit. The other two countries, Norway and Sweden, reveal similar time series trends for bank credit and private credit. Based upon this, the private loans in our sample countries are mainly dominated by deposit money banks.

The fixed effect model is commonly used to mitigate the omitted variable problem. Since the PMG model is based on the framework of the fixed effect model, ignoring some control variables used in the growth literature will not lead to biased results.

The sample period dates back to 1980, the year in which life insurance data for Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Portugal first became available in the database. Besides, while choosing sample data, we face the trade-off between the duration of the sample period and the number of European countries in the sample, since financial development and life insurance sector data of individual countries became available at different points in time. Therefore, we choose to extend the European countries to 17, thus taking our sample period up to 2015.

This study constructs one-way impacts of financial intermediations on real economic performance because of a considerable number of theoretical and empirical studies. First, numerous theoretical frameworks have been proposed to indicate how financial institutions affect economic growth through various channels (e.g. Diamond and Dybvig 1983; Greenwood and Jovanovic 1990; Bencivenga and Smith 1991; Saint-Paul 1992; Pagano 1993; Bencivenga et al. 1995; Greenwood and Smith 1997; Huybens and Smith 1999; Wu et al. 2010). Second, many empirical studies have documented that financial development affects economic development (e.g. Goldsmith 1969; McKinnon 1973; Merton 1990; King and Levine 1993; Gunther et al. 1995; Minsky 1995; Levine and Zervos 1998; Levine et al. 2000; Aretis et al. 2001; Beck and Levine 2004; Rioja and Valev 2004b; Loayza and Ranciere 2006; Cheng and Degryse 2010; Han et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2010; Hassan et al. 2011; Lee 2013; Cheng 2012; Cheng et al. 2014; Law and Singh 2014; Hou and Cheng 2017; Cheng and Hou 2020).

For a more detailed discussion, see Loayza and Ranciere (2006, p. 1057).

Bank credit is measured by the ratio of the credits by deposit money banks to GDP. Unlike private credit, this variable does not consider non-bank credits to the private sector; therefore, it is a less thorough measurement of the development of a financial intermediary (Beck et al. 2000). However, Beck et al. (2000) indicated that the correlation between private credit and bank credit is 0.92, which is an extremely high correlation.

We note that the significantly negative short-run effects reported in Table 3 turn significantly positive after excluding five countries suffering a series of European sovereign debt crises from our sample countries. In other words, the remaining 12 countries have relatively stable economies, suggesting that providing very large loans in financial markets with proper monitoring stimulates investment markets and, in turn, promotes short-term economic growth.

References

Adams, M., J. Andersson, L.F. Andersson, and M. Lindmark. 2009. Commercial banking, insurance and economic growth in Sweden between 1830 to 1998. Accounting, Business and Financial History 19: 21–38.

Apergis, N., and T. Poufinas. 2020. The role of insurance growth in economic growth: Fresh evidence from a panel of OECD countries. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 53: 101217.

Arcand, J.L., E. Berkes, and U. Panizza. 2015. Too much finance? Journal of Economic Growth 20: 105–148.

Arena, M. 2008. Does insurance market activity promote economic growth? A cross-country study for industrialized and developing countries. Journal of Risk and Insurance 75: 921–946.

Arestis, P., P.O. Demetriades, and K.B. Luintel. 2001. Financial development and economic growth: The role of stock markets. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 33: 16–41.

Arghyroua, M.G., and A. Kontonikas. 2012. The EMU sovereign-debt crisis: Fundamentals, expectations and contagion. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money 22: 658–677.

Balcilar, M., R. Gupta, C.C. Lee, and G. Olasehinde-Williams. 2020. Insurance-growth nexus in Africa. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 45: 335–360.

Beck, T., T. Chen, C. Lin, and F.M. Song. 2016. Financial innovation: The bright and the dark sides. Journal of Banking and Finance 72: 28–51.

Beck, T., H. Degryse, and C. Kneer. 2014. Is more finance better? Disentangling intermediation and size effects of financial systems. Journal of Financial Stability 10: 50–64.

Beck, R., G. Georgiadis, and R. Straub. 2014. The finance and growth nexus revisited. Economics Letters 124: 382–385.

Beck, T., and R. Levine. 2004. Stock markets, banks, and growth: Panel evidence. Journal of Banking and Finance 28: 423–442.

Beck, T., R. Levine, and N. Loayza. 2000. Finance and the sources of growth. Journal of Financial Economics 58: 261–300.

Beck, T., and I. Webb. 2003. Economic, demographic, and institutional determinants of life insurance consumption across countries. World Bank Economic Review 17: 51–88.

Bencivenga, V.R., and B.D. Smith. 1991. Financial intermediation and endogenous growth. Review of Economic Studies 58: 195–209.

Bencivenga, V.R., B.D. Smith, and R.M. Starr. 1995. Transactions costs, technological choice, and endogenous growth. Journal of Economic Theory 67: 153–177.

Browne, M., and K. Kim. 1993. An international analysis of life insurance demand. Journal of Risk and Insurance 60: 616–634.

Catalan, M., G. Impavido, and A.R. Musalem. 2000. Contractual savings or stock markets development: Which leads? World Bank Policy Research Paper No. 2421.

Cheng, S.Y. 2012. Substitution or complementary effects between banking and stock markets: Evidence from financial openness in Taiwan. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 22: 508–520.

Cheng, X., and H. Degryse. 2010. The impact of bank and non-bank financial institutions on local economic growth in China. Journal of Financial Services Research 37: 179–199.

Cheng, S.Y., C.C. Ho, and H. Hou. 2014. The finance-growth relationship and the level of country development. Journal of Financial Services Research 45: 117–140.

Cheng, S.Y., and H. Hou. 2020. Do non-intermediation services tell us more in the finance–growth nexus?: Causality evidence from eight OECD countries. Applied Economics 52: 756–768.

Christopoulos, D.K., and E.G. Tsionas. 2004. Financial development and economic growth: Evidence from panel unit root and cointegration tests. Journal of Development Economics 73: 55–74.

Dell’Ariccia, G., and R. Marquez. 2006. Lending booms and lending standards. Journal of Finance 61: 2511–2546.

Diamond, D.W., and P.H. Dybvig. 1983. Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity. Journal of Political Economy 91: 401–419.

Din, S.M.U., A. Regupathi, A. Abu-Bakar, C.C. Lim, and Z. Ahmed. 2020. Insurance-growth nexus: A comparative analysis with multiple insurance proxies. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 33: 604–622.

Easterly, W., R. Islam, and J. Stiglitz. 2000. Shaken and stirred, explaining growth volatility. Annual Bank Conference on Development Economics. Washington DC: World Bank.

Gaytan, A., and R. Ranciere. 2003. Banks, liquidity crises and economic growth. Mimeo: International Monetary Fund and University of de Mexico.

Goldsmith, R.W. 1969. Financial structure and development. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Greenwood, J., and B. Jovanovic. 1990. Financial development, growth and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy 98: 1076–1107.

Greenwood, J., and B.D. Smith. 1997. Financial markets in development and the development of financial markets. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 21: 145–181.

Gunther, J.W., C.S. Lown, and K.J. Robinson. 1995. Bank credit and economic activity: Evidence from the Texas banking decline. Journal of Financial Services Research 9: 31–48.

Haiss, P., and K. Sumegi. 2008. The relationship between insurance and economic growth in Europe: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Empirica 35: 405–431.

Han, L., D. Li, F. Moshirian, and Y. Tian. 2010. Insurance development and economic growth. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 35: 183–199.

Hassan, M.K., B. Sanchezb, and J.-S. Yuc. 2011. Financial development and economic growth: New evidence from panel data. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 51: 88–104.

Hou, H., and S.Y. Cheng. 2017. The dynamic effects of banking, life insurance, and stock markets on economic growth. Japan and the World Economy 41: 87–98.

Huybens, E., and B.D. Smith. 1999. Inflation, financial markets, and long-run real activity. Journal of Monetary Economics 43: 283–315.

Imbs, J. 2007. Growth and volatility. Journal of Monetary Economics 54: 1848–1862.

King, R.G., and R. Levine. 1993. Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Quarterly Journal of Economics 108: 717–737.

Law, S.H., and N. Singh. 2014. Does too much finance harm economic growth? Journal of Banking and Finance 41: 36–44.

Lee, C.C. 2013. Insurance and real output: The key role of banking activities. Macroeconomic Dynamics 17: 235–260.

Lee, C.C., C.C. Lee, and Y.B. Chiu. 2013. The link between life insurance activities and economic growth: Some new evidence. Journal of International Money and Finance 32: 405–427.

Levine, R. 1997. Financial development and economic growth: Views and agenda. Journal of Economic Literature 35: 688–726.

Levine, R. 2005. Finance and growth: Theory and evidence. Handbook of Economic Growth 1: 865–934.

Levine, R., N. Loayza, and T. Beck. 2000. Financial intermediate and growth: Causality and causes. Journal of Monetary Economics 46: 31–77.

Levine, R., and S. Zervos. 1998. Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. American Economic Review 88: 537–558.

Li, D., F. Moshirian, P. Nguyen, and T. Wee. 2007. The demand for life insurance in OECD countries. Journal of Risk and Insurance 74: 637–652.

Lindh, T. 2000. Short-run costs of financial market development in industrialized economies. Eastern Economic Journal 26: 221–239.

Loayza, N.V., and R. Ranciere. 2006. Financial development, financial fragility, and growth. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 38: 1051–1076.

Lucas, R. 1988. On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42.

McKinnon, R.I. 1973. Money and capital in economic development. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Merton, R.C. 1990. The financial system and economic performance. Journal of Financial Services Research 4: 263–300.

Minsky, H.P. 1995. Financial factors in the economics of capitalism. Journal of Financial Services Research 9: 197–208.

Mishkin, F.S. 2007. Is financial globalization beneficial? Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 39: 259–294.

Outreville, J.F. 1990. The economic significance of insurance markets in developing countries. Journal of Risk and Insurance 57: 487–498.

Outreville, J.F. 2013. The relationship between insurance and economic development: 85 empirical papers for a review of the literature. Risk Management and Insurance Review 16: 71–122.

Pagano, M. 1993. Financial markets and growth: An overview. European Economic Review 37: 613–622.

Pesaran, M.H. 2004. General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. Cambridge Working Papers in Economics No. 435, University of Cambridge, and CESifo Working Paper Series No. 1229.

Pesaran, M.H. 2007. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics 22: 265–312.

Pesaran, M.H., Y. Shin, and R.P. Smith. 1999. Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association 94: 621–634.

Pesaran, M.H., and R.P. Smith. 1995. Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics 68: 79–113.

Rajan, R.G. 2006. Has finance made the world riskier? European Financial Management 12: 499–533.

Rajan, R.G., and L. Zingales. 2003. The great reversals: The politics of financial development in the twentieth century. Journal of Financial Economics 69: 5–50.

Rioja, F., and N. Valev. 2004a. Finance and the sources of growth at various stages of economic development. Economic Inquiry 42: 127–140.

Rioja, F., and N. Valev. 2004b. Does one size fit all? A reexamination of the finance and growth relationship. Journal of Development Economics 74: 429–447.

Saint-Paul, G. 1992. Technological choice, financial markets and economic development. European Economic Review 36: 763–781.

UNCTAD. 1964. Proceedings of the United Nations conference on trade and development, first session, vol. 1, final act and report. Geneva: United Nations.

Ward, D., and R. Zurbruegg. 2000. Does insurance promote economic growth? Evidence from OECD countries. Journal of Risk and Insurance 67: 489–506.

Webb, I., M.F. Grace, and H. Skipper. 2002. The effect of banking and insurance on the growth of capital and output. Center for Risk Management and Insurance Working Paper 02.

Wu, J.L., H. Hou, and S.Y. Cheng. 2010. The dynamic impacts of financial institutions on economic growth: Evidence from the European Union. Journal of Macroeconomics 32: 879–891.

Yanikkaya, H. 2003. Trade openness and economic growth: A cross-country empirical investigation. Journal of Development Economics 72: 57–89.

Funding

NSC 99-2410-H-262-016- (Ministry of Since and Technology, Taiwan).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The contribution is free from any conflicts of interest, including all financial and non-financial interests and relationships.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Variable definitions

See Table 6.

Appendix 2: Methodology

Panel unit root tests

This paper examines the stationarity of variables using the panel unit root test of Pesaran (2007) that allows for cross-sectional dependence. Before adopting the panel unit-root test, a cross-sectional dependence (CD) test developed by Pesaran (2004) is used to examine the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence among individuals in the panel:

where \(\overline{\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{\rho } } = \left( {\frac{2}{N(N - 1)}} \right)\sum\limits_{i = 1}^{N - 1} {\sum\limits_{j = i + 1}^{N} {\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{\rho }_{ij} } }\), in which \(\overset{\lower0.5em\hbox{$\smash{\scriptscriptstyle\frown}$}}{\rho }_{ij}\) is the pair-wise cross-sectional correlation coefficients of residuals from the conventional Augmented Dicky-Fuller (ADF) regression. T is the sample period and N is the cross-section dimension.

Next, consider the following cross-sectionally augmented Dickey–Fuller (CADF) regression:

where \(\overline{y}_{t} = {{\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{N} {y_{it} } } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{N} {y_{it} } } N}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} N}\) is the cross-sectional mean of \(y_{it}\). The purpose of including the cross-sectional mean in the above equation is to control for contemporaneous correlation among \(y_{it}\). The null hypothesis of the test can be expressed as \(H_{0} :\beta_{i} = 0\) for all i against the alternative hypothesis \(H_{1} :\beta_{i} < 0\) for some i.

The test statistic (CIPS) provided by Pesaran (2007) is given by:

where \(t_{i} (N,T)\) is the t statistic of \(\beta_{i}\) in Eq. (13). To avoid the problem of extreme statistics caused by small sample observations, Pesaran (2007) constructs a truncated version of the CIPS, denoted as CIPS*. The critical values for both tests are given in Table II(c) of Pesaran (2007).

Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels

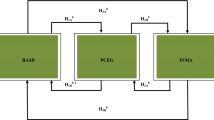

This paper utilises PMG estimators, provided by Pesaran et al. (1999), to estimate the long- and short-run elasticity of life insurance and banking on economic development. The major characteristic of PMG estimators is that it allows the intercepts, short-term coefficients and error-correction coefficients to be country specific, but restricts the long-run coefficients to be the same.

The error-correction form of an autoregressive distributed lag model, ARDL(p, q), is written as follows:

where \(X_{i,t} = \left( {LI_{i,t} ,FD_{i,t} } \right)^{\prime }\) in which LI and FD are indicators of life insurance and financial development; p and q are the lag order for dependent and independent variables, respectively; \(\beta\) is a vector of long-run coefficients, measuring the possible impacts of life insurance and banking (Xi,t−1) on the real economic sector (Yi,t−1); \(\alpha_{ik}\) and \(\gamma_{ij}\) are short-run coefficients, representing the influences of difference development variables (\(\Delta Y_{i,t - k}\) and \(\Delta X_{i,t - j}\)) on growth rate (\(\Delta Y_{i,t}\)); and \(\phi_{i}\) is the speed of adjustment to the long-run equilibrium.

To construct the estimators, Pesaran et al. (1999) suggest jointly estimating the long-run slope coefficients \(\left( \beta \right)\) across agents through a maximum likelihood (MLE) approach. Once the pooled MLE of the long-run parameters is successfully computed, the short-run and error-correction coefficients can be consistently estimated by running the individual MLE. Therefore, the mean of error-correction coefficient \(\left( {\phi_{MG} } \right)\) and short-run coefficients (\(\alpha_{MG}\) or \(\lambda_{MG}\)) follow asymptotic normality and can be calculated by the equal weighted average of individual coefficients:

where \(z = \alpha \,\) and \(\gamma\).

As shown in Pesaran et al. (1999, pp. 625–626), the PMG estimator can be computed using the same algorithm regardless of whether the regressors are integrated of order 1 or order 0, I(1) or I(0). Furthermore, the PMG estimates will be consistent if the regression residuals are independent. Note that by properly choosing lag order p and q, the time-series independence of the disturbances can be satisfied. Next, the common-time period effect is modelled by expressing the regression variables as deviations from their corresponding cross-sectional means in each period, to ensure that the disturbances are independently distributed across countries (Pesaran et al. 1999).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, SY., Hou, H. Financial development, life insurance and growth: Evidence from 17 European countries. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 47, 835–860 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-021-00247-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-021-00247-1