Abstract

The United Nations (UN) recognises free school meals as critical, yet widely disrupted by COVID-19. We investigate caregiver perceptions and responses to interruptions to the universal infant free school meal programme (UIFSM) in Cambridgeshire, England, using an opt-in online survey. From 586 responses, we find 21 per cent of respondents’ schools did not provide UIFSM after lockdown or advised caregivers to prepare packed lunches. Where provided, caregivers perceived a substantial decline in quality and variety of meals, influencing uptake. Direction to bring packed lunches, which caregivers reported to have contained ultra-processed foods of lower nutritional quality, influenced caregiver behaviour rather than safety concerns as claimed by industry. The quality and variety of meals, and school and government policy, had greater impact than concerns for safety. In the UK and at the international level, policymakers, local governments, and schools must act to reverse the trend of ultra-processed foods in packed lunches, while improving the perceived quality of meals provided at schools.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Key messages

-

School meals are a critical nutritional and educational intervention, yet the COVID-19 pandemic eroded school meal provision and set back progress.

-

Caregivers shifted away from school meals and towards packed lunches during the pandemic not because of concerns about safety, but rather because of a lack of provision at schools or a decrease in the quality and variety of school meals.

-

Children from lower income households were least likely to go to schools that provided meals during lockdown and most likely to receive ultra-processed packed lunches.

Introduction

In November 2021, the United Nations (UN) announced a school meals coalition involving five UN agencies: the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), the UN World Food Programme (WFP), and the World Health Organization (WHO), and more than 50 partners including non-government organisations, civil society, and foundations [1]. It noted that these school meal programmes contribute to achieving at least seven of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including “those related to poverty (SDG1), hunger and all forms of malnutrition (SDG2), health (SDG3), education (SDG4), gender equality (SDG5), sustainable consumption and production (SDG12) and partnerships (SDG17)” [2]. As a result, the UN encouraged governments to commit universally to deliver school meals to every child in the world by 2030 [2].

Extensive research that identifies meals eaten in education and care settings as having a substantial impact on a child’s total diet validates the UN position [3]. Food and drink provided in schools influence healthy dietary behaviour during the life stage when eating habits and food preferences are being formed [3]. As a result, some have gone so far as to suggest that a government’s failure to provide healthy foods in schools amounts to a breach of a child’s human rights [4].

In England, schools have offered meals for over 150 years. A variety of overlapping programmes promote school meals for children in state supported schools. Since 2014, the universal infant free school meals programme (UIFSM) has provided all children in Reception, Year One and Year Two (children from four to seven years of age) of state-funded primary schools with a free meal, unless caregivers (people with parental responsibility, or guardians) opt otherwise [5]. These three cohorts of children are eligible for a two-course meal worth approximately £2 a day, including a hot option. The UK implemented this programme following an independent report, the School Food Plan (2013).

The then-coalition government initiated UIFSM to “ease the pressure on households, encourage healthy eating and … raise educational performance” [6]. Studies have documented that UIFSM boosted children’s health and educational performance [7]. The provision also appears to have promoted greater uptake of free school meals among those who would otherwise have qualified via means-testing, as demonstrated during the UK Government’s UIFSM pilot scheme [8].

Yet the COVID-19 pandemic heavily impacted school meal provision in England. The Government closed schools in England to most pupils on the afternoon of 20 March 2020 for an indefinite period, with only the children of key workers (people in private or public sector employment that the Government considered to be essential to society) and vulnerable children (those with a social worker, children in care, and those with complex special educational needs) permitted to attend from thereon in. The Department of Education suspended UIFSM on 20 March 2020 and only began to reinstate UIFSM during the phased reopening of primary schools from 1 June 2020 [9]. A replacement voucher system was offered to pupils who qualified for means-tested free school meals through low household income. Separately, many schools continued to provide in-person school meals for the vulnerable children and children of keyworkers who attended during the lockdown, although some schools choose not to continue this provision or advised pupils to bring in packed lunch where possible [9].

The Grocer, a prominent 150-year old trade magazine that covers food and beverage retail developments, publicly and widely suggested that there would be a decline in uptake of school meals due to caregivers’ concerns about ‘hygiene and safety’ in light of the COVID-19 crisis. It argued that caregivers would instead prefer to pack lunches for their children [10]. Past research demonstrates that packed lunches prepared by caregivers rarely meet the nutritional standards of school meals in the UK [9, 11], and are often low in nutritional value overall [12]. This problem is likely to have been amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic, with The Grocer emphasising a natural priority for a safe meal [10]. Caregivers may have increased provision of packed lunches even if they lacked the financial or temporal resources to make it nutritious. Fewer than two fifths of British adults surveyed in July 2020 reported feeling ‘comfortable’ about returning to eating outdoors at cafes and restaurants [13], indicating widespread public concern about the sanitation of food catering.

Here, we examine the extent to which schools sustained UIFSM and explore any shifts in caregivers’ perceptions and uptake in one local authority in Cambridge, England. We sought to explore whether the suggestion that caregivers are worried about safety is driving reduced usage. Second, we investigated the potential healthiness of substitute meals caregivers provided when schools did not offer UIFSM or caregivers did not prefer them. As low-income groups are most negatively affected by COVID-19 [14, 15], and least able to afford nutritious packed lunches for their children, we also examine whether income status impacted caregivers’ perceptions of UIFSM safety, their willingness to continue using UIFSM, or both.

Data and methods

Participants

According to the local authority, Cambridge, England had registered 2415 children in Reception and Year One in 2019–2020. We recruited their caregivers using an online snowball sampling method on social media, Facebook and Twitter, and by sending emails from schools, food banks, childcare services and afterschool care bodies, community hubs, and university bodies to parenting lists. We expanded the snowball sample by asking participating caregivers to pass the survey to others who might be eligible.

We posed screening questions to those who wished to participate in this study if they identified themselves as living in Cambridge and being the caregiver of a child in Reception or Year One who had returned to school after the lockdown in June 2020. We assumed the maximum number of participating families to be 2415, although some of the children may be siblings or children from a multiple birth (such as twins or triplets), making the number of eligible respondents likely lower.

Design

We collected data using an online questionnaire administrated via Qualtrics during July and August 2020. We instructed participants to follow a link to the website that presented information on the study, consents, and resources for those struggling to afford food. The average time participants took to complete a response was 2 min 20 s.

We adapted questions from those field tested by Ohri-Vachaspati and colleagues in 2013 to explore caregivers’ perceptions of school lunches in the United States (US) [16]. To identify whether lockdown affected UIFSM usage we asked participants to respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to the statements:

-

“Before lockdown, my child ate a school-provided lunch on most days”, and

-

“Since March 23, my child has eaten a school-provided lunch on most days they have been in attendance”.

To ascertain whether there had been a drop in perceived quality of UIFSM, we asked:

-

“Regardless of whether your child eats school meals, how would you rate the nutritional quality of free infant school meals before lockdown?”, and

-

“Regardless of whether your child eats school meals, how would you rate the nutritional quality of free infant school meals since March 23?”.

Participants could respond: ‘very unhealthy’, ‘unhealthy’, ‘healthy’, ‘very healthy’, or, for the latter question, they could select instead: ‘the school has not provided food to students since March 23’. We tested caregivers’ perceptions of variety using the same question template, and participants were able to choose from: ‘very poor variety’, ‘poor variety’, ‘adequate variety’, ‘excellent variety’ or, for the latter question, ‘the school has not provided food to students since March 23’.

Next, our survey asked participants, “If you have been sending your child to school with a packed lunch since the introduction of lockdown, why is this?”. Participants could select all applicable options:

-

“The school has not provided meals to students”,

-

“The school advised caregivers to send packed lunch”,

-

“There has been a reduction in the nutritional quality of school meals”,

-

“There has been a reduction in the variety of school meals”, and

-

“Increased concern about the hygiene/safety of school meals”.

We provided space for respondents to write out their own answers. This was followed by four open-answer questions, allowing participants to write comments in response to the following:

-

“Please outline any concerns you had about school meals before lockdown”.

-

“Please outline any concerns you had about school meals since March 23”.

-

“If you send your child with a packed lunch, what do you generally provide? Examples: a sandwich, piece of fruit, pre-packaged food, crisps, fruit juice, chocolates, cheese, cold pizza, leftovers, salad, chopped vegetables, or the like”.

-

“Any further comments?”

Data analysis

We used descriptive and inferential statistics to analyse multiple-choice questions. We explored the answers to open questions using a text analysis method called topic modelling, a data-driven approach to explore topics in texts, speeches, blog posts etc. Social scientists have commonly applied topic modelling since the 2010s [17, 18]. This method uses an algorithm, Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), to extrapolate topics from texts. The algorithm is based on an assumption that every document (in this case, comment) is a combination of different topics [19], and it infers the latent topic structure of documents. While scanning all documents, it randomly assigns each word to a topic and then, document by document, it reassigns words to topics based on the probability that a word belongs to a topic over the entire corpus, and that a topic is contained in a specific document [20]. The method allowed for collection of text from the comment boxes into a corpus, pre-processed and analysed with the Gensim package in Python. We then associated the most frequent topic to each question and survey participant. We then use a logistic regression to test the effect of self-reported income on the attitudes towards school-provided meals, controlling for ethnicity and wards.

Ethics

The Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge granted Ethical approval for this study on 21 July 2020.

Results

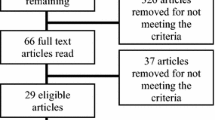

We received completed surveys from 586 respondents (24.3% of the population). We did not require participants to answer every question presented.

Caregivers’ reported use of the free school meal system

Before lockdown almost 90% (n = 308) of the respondents reported that their children received school-provided lunches at school on most days before lockdown. This figure dropped to 53% (n = 182) after 23 March 2020. Notably, 21% (n = 72) of the respondents reported that their school did not provide any lunch after the lockdown.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of respondents using school-provided meals by demographics before and after the lockdown. We found some variation across ethnicities and location, although before the lockdown, caregivers from Asian backgrounds reported less use of the school-provided meal system. After the lockdown, caregivers self-identifying as Arab reported the largest drop.

As for income, we find variation across groups both in post-lockdown and pre-lockdown. Before the lockdown, there was no significant difference in reported use of the school meal system across income groups. Caregivers in our second lowest income group (£10,000–25,000) were the least likely to use school-provided meals, and caregivers in the lowest income group (under £10,000) reported marginally lower use than caregivers earning between £25,000–50,000 and £50,000–100,000. We see a different trend after the lockdown. As Fig. 1 (right panels) demonstrates, caregivers in the two lowest income groups (under £10,000 and £10–25,000) became marginally more likely to use the free school meal system than those in the groups £25,000-£50,000 and £50,000-£100,000.

Caregivers’ perception of school meals

We analysed caregivers’ perceptions of school meals before and after the lockdown. Before the lockdown, 85% of the respondents (n = 291) considered the meals healthy or very healthy and only 15% (n = 53) considered them unhealthy or very unhealthy. After the lockdown, the percentage of those claiming that the meals were healthy or very healthy declined to 48% (n = 166) and those considering them unhealthy or very unhealthy increased to 31% (n = 105).

A similar trend is present for the variety of food offered. Before the lockdown 84% (n = 290) of caregivers reported that the food variety was adequate or excellent. This proportion declined to 25% (n = 86) after the lockdown. About 20% of respondents reported that their schools did not provide meals during lockdown. We see a decrease in perception of nutritional quality and variety.

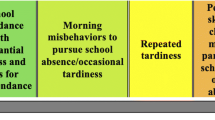

What reasons did caregivers give for sending their children to schools with packed lunch since the lockdown? Eight per cent (n = 26) reported an increase in concerns about hygiene and safety as the reason. Another 28% (n = 85) identified reduction in the variety of school meals. Another 15% (n = 45) reported packing lunches because the school stopped providing meals, and 11% (n = 33) said that they shifted to packed lunches because the school advised them to do so.

Packed lunches

We rely on the topic modelling approach to analyse the open question “Q13—if you send your child with a packed lunch, what do you generally provide? Examples: a sandwich, piece of fruit, pre-packaged food, crisps, fruit juice, chocolates, cheese, cold pizza, leftovers, salad, chopped vegetables, or the like”. Supplemental Figure S1 shows the word clouds (a way to represent groups of words in which the size of the font is proportional to the frequency of the word) for the four topics extracted from the answers to this question. It displays the most important words for each topic (the larger the font, the higher the importance of the word). The four topics reflect four recurrent diets of children after lockdown. Although both most frequently recurring topics contain the word ‘fruit’, one topic represents a healthier diet than the other: Topic 1 containing words such as ‘salad’, ‘cucumber’ and ‘grape’, and Topic 3 containing words such as ‘bar’, ‘crisp’ and ‘chop’.

What type of lunches did respondents from lower and higher income groups give to their children? Supplemental Figure S2 shows the results from lower income respondents and Supplemental Figure S3 shows those from higher income respondents. In Supplemental Figure S3, words like ‘fruit’, ‘vegetable’, ‘salad’, ‘chop’, ‘cucumber’, ‘water’ and ‘yoghurt’ recur most frequently. In Supplemental Figure S3, ‘wrap’, ‘treat’, ‘sandwich’ and ‘bar’ recur among the most frequently used words. We conclude that students from lower income households go to school with less healthy packaged food than the others.

Logistic regression

Some inferential statistics provide reasons why caregivers report a change in behaviours. Table 1 shows results of a logistic model. By regressing attitudes towards school meals on respondents’ income, we look at variation in attitudes across individuals from different income groups, controlling for the ward and ethnic background. We find a statistically significant relationship between self-reported income and attitudes towards change in nutritional quality in school meals, but not in attitudes towards their variety. The higher the income, the higher the likelihood of respondents having perceived a reduction in nutritional quality. We find a statistically significant relationship between income and whether the school asked the caregiver to provide the students with packed meals during lockdown, but not whether the school stopped providing meals during lockdown. The higher the income, the lower the likelihood that school asked caregivers to provide lunch. We do not find any effect for hygiene concerns.

Discussion

Our findings validate the vulnerability of school meals during the COVID-19 pandemic, as set out by the UN in its statements about public health crises. We found a considerable drop in the number of children benefitting from the UIFSM scheme after lockdown compared to caregiver reported uptake pre-lockdown. This is a worrying development given the central role that UIFSM has played in improving child nutrition since its introduction in 2014, and in light of the commitments by the UN to encourage greater school meal provision, uptake, and quality around the world by 2030 [2].

UK research demonstrates that UIFSM improved health outcomes and, in almost all instances, school meals have been more healthful than packed lunches provided by caregivers [9, 11]. Our study corroborates this existing evidence, as our analysis confirms that caregivers provided a higher degree of ultra-processed foods in packed lunches.

Need for policy change is urgent to sustain child nutrition gains made in recent years. During the lockdown period in early 2021 media attention featured poor government provision. This prompted public debate over whether payments, vouchers, or packages would provide the best replacement for free school meals for families struggling to feed children home schooling during closures [21]. Participants in our study showed negligible concern with the safety and hygiene of school meals. They reported most frequently instead that the barriers to using school means was their absence, and, when present, that the meals offered poor quality and variety. This result confirms findings in other countries that perception of quality impacts school meal uptake to a notable extent [22].

Study limitations

Our study had several limitations. We explored perceptions only in one city in England, although it is one of the most socioeconomically diverse cities, often rated as one of England’s most unequal places [23]. Future research would benefit from a longer study across more locations to learn about the role of socio-economic status of caregivers as well as regional variation.

We used social media distribution and a snowball sample, which necessarily limits participation to a self-selected group of caregivers willing to participate. The requirement that caregivers fill in a short questionnaire would exclude those with limited English language skills, whether migrant caregivers or native British caregivers with low levels of literacy, or those without access to devices through which we distributed the survey. It is very likely that the questionnaire did not reach the most deprived caregivers in Cambridge. Our findings may not be generalisable to other urban, low-income, and ethnically and racially diverse communities. With immigrant, minority ethnic, Black and Asian communities disproportionately affected by the pandemic[24], such research is critical.

We based information on school meal participation on caregiver reports. Although there may be some discrepancies between caregiver reports and actual school meal participation, we focused on caregivers’ perceptions of school meals, and thus, caregiver reports of whether their child eats school meals. The relationship between participation and perception is critical to tailoring effective interventions and our study confirms findings in the US which suggest that influencing parental perceptions remains central [22].

Implications

The UN recognises school meals as critical nutritional and educational interventions, leading it to push for every child to receive a school meal by 2030 wherever they are in the world [2]. Our survey validated suggestions that the pandemic eroded school meal provision, set back progress, and identified some evidence of a shift to packaged lunches containing ultra-processed foods and drinks. Contrary to suggestions in industry press, caregivers were not particularly concerned about safety. Instead, they moved to packed lunches (1) due to a lack of meal provision at schools; (2) on direction by the school to bring packed lunches; or (3) because of a decrease in the quality and variety of school meals.

The shift has disproportionately affected children from lower income households in Cambridge in two ways: (1) these children were less likely to go to schools that provided meals during lockdown, and (2) caregiver self-reported contents of packed lunches suggest inclusion of more pre-packaged foods more likely to be ultra-processed than school meal contents. More research is needed on socio-economic deprivation in England and beyond, not just because COVID’s impacts have been most burdensome on families in terms of mortality and socio-economic reverberations, but also because children in these areas were most likely to be in schools not providing meals.

Conclusions

Our study validates that perceptions of quality and variety impact on uptake, and demonstrates the impact of policy to influence provision of school meals. Policy makers should be concerned with making school meals available, and assure they are “safe, nutritious and sustainably produced” [2]. In future policies they should also address potential environmental and cost impacts of food waste from these meals [25]. Public health and nutrition researchers should advocate for improvements in school meals and engage non-government organisations to work with government at all levels (national and local), educational providers, and communities to develop and expand school meals, and thereby make our food systems more sustainable.

Data availability

All data can be access at: https://ql.tc/ouMyCu.

References

World Food Programme. UN Agencies back bold plan to ensure every child in need gets a regular healthy meal in school by 2030. World Food Program 2021. https://www.wfp.org/news/un-agencies-back-bold-plan-ensure-every-child-need-gets-regular-healthy-meal-school-2030. Accessed 29 Nov 2021

United Nations. School Meals Coalition : Nutrition , Health and Education for Every Child Declaration of Support 2021:1–2.

Mikkelsen BE, Rasmussen VB, Young I. The role of school food service in promoting healthy eating at school—a perspective from an ad hoc group on nutrition in schools, Council of Europe. Food Serv Technol. 2005;5:7–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-5740.2005.00110.x.

Mikkelsen BE, Engesveen K, Afflerbach T, Barnekow V. The human rights framework, the school and healthier eating among young people: a European perspective. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19:15–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015001627.

Long R. School meals and nutritional standards. London: 2015.

Deputy Prime Minister’s Office, Department for Education, Clegg TRHN, Laws TRHD. Deputy Prime Minister launches free school meals. GOVUK 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/deputy-prime-minister-launches-free-school-meals. Accessed 2 Aug 2020

Sellen P, Huda N, Gibson S, Oliver L. Evaluation of Universal Infact Free School Meals. 2018.

Kitchen S, Tanner E, Brown V, Natcen CP, Crawford C, Dearden L. Evaluation of the Free School Meals Pilot Impact Report 2013:1–153.

Department of Education. Providing free school meals during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. GovUk 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-free-school-meals-guidance/covid-19-free-school-meals-guidance-for-schools. Accessed 2 Aug 2020

The Grocer. The Covid school lunch: kids’ lunches category report 2020. 2020.

Goodchild GA, Faulks J, Swift JA, Mhesuria J, Jethwa P, Pearce J. Factors associated with universal infant free school meal take up and refusal in a multicultural urban community. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2017;30:417–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12442.

Evans CEL, Melia KE, Rippin HL, Hancock N, Cade J. A repeated cross-sectional survey assessing changes in diet and nutrient quality of English primary school children’s packed lunches between 2006 and 2016. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e029688. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2019-029688.

Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain. OnsGovUk 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandwellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandthesocialimpactsongreatbritain/10july2020. Accessed 2 Aug 2020

Caul S. Deaths involving COVID-19 by local area and socioeconomic deprivation - Office for National Statistics. OnsGovUk n.d. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsinvolvingcovid19bylocalareasanddeprivation/deathsoccurringbetween1marchand31may2020. Accessed 2 Aug 2020

Public Health England. Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19 2020:89.

Ohri-Vachaspati P. Parental perception of the nutritional quality of school meals and its association with students’ school lunch participation. Appetite. 2014;74:44–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.024.

Lucas C, Nielsen RA, Roberts ME, Stewart BM, Storer A, Tingley D, et al. Computer-assisted text analysis for comparative politics. Polit Anal. 2015;4:254–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpu019.

Roberts ME, Stewart BM, Tingley D, Lucas C, Leder-Luis J, Gadarian SK, Albertson B, Rand DG. Structural topic models for open-ended survey responses. Am J Polit Sci. 2014;58(4):1064–82.

Grimmer J, Stewart BM. Text as data: The promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit Anal. 2013;21:267–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028.

Blei DM, Ng AY, Edu J. Latent Dirichlet allocation Michael I. Jordan. J Mach Learn Res. 2003;3(2):993–1022.

Kerridge K. Free school meal handouts strip agency from UK parents . Financ Times 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/8df76a21-706d-4ab2-9e69-475d35fb8c41. Accessed 11 Sept 2020

Martinelli S, Acciai F, Au LE, Yedidia MJ, Ohri-Vachaspati P. Parental perceptions of the nutritional quality of school meals and student meal participation: before and after the healthy hunger-free kids act. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2020.05.003.

Ferguson D. Beyond Cambridge’s colleges, UK’s most unequal city battles poverty | UK news | The Guardian. Guard 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jan/12/beyond-cambridge-spires-most-unequal-city-tackles-poverty. Accessed 11 Sept 2020

Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by ethnic group, England and Wales 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/coronavirusrelateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales/2march2020to10april2020?hootPostID=b229db5cd884a4f73d5bd4fadcd8959b. Accessed 11 Sept 2020

García-Herrero L, De Menna F, Vittuari M. Food waste at school. The environmental and cost impact of a canteen meal. Waste Manag. 2019;100:249–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WASMAN.2019.09.027.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ED and SS devised the study and undertook the collection of data. ED and MT processed and analysed the data. All authors participated in the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

None.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The POLIS Ethics Committee at the University of Cambridge approved the study on 22 July 2020.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Davies, E., Vannoni, M. & Steele, S. Caregiver perceptions of England’s universal infant school meal provision during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Public Health Pol 44, 47–58 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-022-00387-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-022-00387-1