Abstract

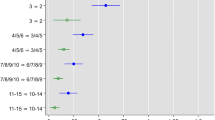

Previous research provides solid evidence for the existence of a ballot position effect. The cognitive mechanisms behind this effect are, however, undertheorized and understudied. We develop and test here ‘voter perception effects’ as a possible explanation. Following this reasoning, the list position in a list-PR system functions as a heuristic cue for the competence of candidates: candidates selected for a high list position are perceived as more competent by voters, even when controlling for other candidate characteristics. Our results, based on an experimental design, show that head of lists are indeed perceived as more competent than middle of list candidates. This is related to both advantages for the first position and to disadvantages related to a middle of list position.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For sake of clarity: the analyses further developed in this paper will focus on three groups. Candidates on top of the list will be referred to as ‘head of list candidates,’ candidates positioned in the middle of the list will be referred to as ‘middle of list candidates,’ and candidates whose list position was not mentioned, will be referred to as the ‘control group.’

The data are publicly available and online accessible at https://zenodo.org/record/1162716#.WnBwHLpFzI.

However, in reality only very few candidates manage to get elected out of order. Some therefore argue that the Belgian system can be better described as a “quasi-closed system” or a “closed system in disguise.”

However, it needs to be noted that the distinguished mechanisms are potentially interrelated. This will be discussed more in-depth in the concluding section.

We are fully aware that also other people (including journalists and leaders of civil society organizations) could use the list position as a heuristic cue when deciding which candidates they will cover or who they will invite for discussing issues, but that falls outside the scope of this study.

It needs to be noted that there is a methodological discussion on how the motives behind preferential voting are best measured: by means of open- or closed-ended questions. Studies that use a closed question, such as Goeminne and Swyngedouw’s study, show that competence is the most important criterion. Studies in which open questions are used also show that competence is an important aspect, but that also other factors, such as issue positions, local embeddedness, and integrity, are at play (André et al. 2015).

Although it would be interesting to see how the competence perception gradually varies over list positions, we had to restrict our analysis, in function of the feasibility of our design, to three experimental conditions. The head of list position is the most visible and most important position. The inclusion of subsequent positions (e.g., second, third) would make our design unnecessarily complex. Moreover, in Belgium, parties often choose experienced politicians for positions at the bottom of the list, so-called ‘list pushers. Therefore, we decided to analyze a middle of list position (in contrast to a head of list position), and not to use the last position as a treatment since this position could also come with a certain quality label.

The same district magnitude was used across all treatments: each list of candidates consisted of twenty candidates, which is a realistic number of candidates for the Flemish constituencies. To refer to the head of list position, we always indicated the first position on the list. To refer to the middle of list position, we always indicated the tenth position on the list.

The other invitations were apparently sent to invalid or outdated email addresses.

Because of the risk of a selection effect (for example, if only politically interested respondents were able to correctly answer this question), we made a comparison between the final sample and respondents who could not answer the manipulation check correctly. This analysis reveals that these groups do not differ substantially on important sociodemographic aspects. There is a small selection bias in that our final sample is slightly higher educated and younger, but there are no striking differences concerning gender and level of political interest.

The average completion time was 996 seconds. The boundary duration from which a response is considered valid was set at 498 seconds.

The provided answer categories for this question were not reliable to assess whether respondents were aware of the fact that the list position of these candidates was not mentioned.

The exclusion of certain groups of respondents does not significantly affect the results. As a robustness check, we ran analyses on the full sample (including the three aforementioned categories of excluded respondents). The results for the full sample are comparable to the results for the more limited sample.

This element will be tackled in another paper which specifically focuses on gender stereotypes in elections.

Voters’ preference for head of list candidates can be driven by different kinds of factors. In order to test for perceptions of competence, we explicitly referred to competence in the questions. The questions were asked in the following way: “How competent do you consider this politician for functioning in politics in general/for the policy domain at stake?” By explicitly mentioning ‘competent’ in the questions, we believe that respondents’ evaluation of the presented candidates is related to this specific aspect.

One-tailed p values were calculated by dividing the significance level, derived in SPSS, by two.

It needs to be noted that there might be small wording effect at play, since the candidates at the head of list presented themselves as “I am head of list for my party” and candidates at the middle of list presented themselves as “I am placed 10th on the ballot.” The first presentation suggests that the candidate enjoys high standing within his/her party, which might point to a difference in leadership.

Subsequent analyses (not in the table) indicate that the perceived competence of the presented candidates is to a large extent influenced by the party preference of the respondents. Respondents whose preferred party is the same as the one ascribed to the hypothetical candidate perceive the candidate as more competent (p = 0.000) and this applies to all policy issues.

The same analysis was made for different subsamples (according to gender, age, ideological positioning, and level of political interest). The general effect is persistent and holds across these different subgroups, which again reinforces the robustness of our findings.

References

Aalberg, T., and A.T. Jenssen. 2007. Gender stereotyping of political candidates. Nordicom Review 28 (1): 17–32.

André, A., P. Baudewyns, S. Depauw, and L. De Winter. 2015. Les motivations du vote de préférence. In Décrypter l’électeur. Le commportement électoral et les motivations du vote, ed. K. Deschouwer, P. Delwit, M. Hooghe, P. Baudewyns, and S. Walgrave, 58–75. Tielt: Lannoo Campus.

André, A., J.-B. Pilet, and B. Wauters. 2010. Voorkeurstemmen bij de regionale verkiezingen van 2009: gebruik en motieven. In De stemmen van het volk. Een analyse van het kiesgedrag in Vlaanderen en Wallonië op 10 juni 2009, ed. K. Deschouwer, P. Delwit, M. Hooghe, and S. Walgrave. Brussel: Brussels University Press.

Bagley, C.R. 1965. Does candidates’ position on the ballot paper influence voter’s choice? A study of the 1959 and 1964 British general elections. Parliamentary Affairs 19 (2): 162–174.

Bein, H.M., and D.S. Hecock. 1957. Ballot position and voter’s choice. The arrangement of names on the ballot and its effect on the voter. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Blom-Hansen, J., J. Elklit, S. Serritzlew, and L.R. Villadsen. 2016. Ballot position and election results: Evidence from a natural experiment. Electoral Studies 44: 172–183.

Brockington, D. 2003. A low information theory of ballot position effect. Political Behavior 25 (1): 1–27.

Deschouwer, K. 2012. The politics of Belgium: Governing a divided society. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Faas, T., and H. Schoen. 2006. The importance of being first: Effects of candidates’ list positions in the 2003 Bavarian state election. Electoral Studies 25 (1): 91–102.

Geys, B., and B. Heyndels. 2003. Influence of ‘cognitive sophistication’on ballot layout effects. Acta Politica 38 (4): 295–311.

Goeminne, B., and M. Swyngedouw. 2007. De glimlach van de kandidaat? Kiezersvoorkeuren in kandidaatskenmerken. In De kiezer onderzocht: de verkiezingen van 2003 en 2004 in Vlaanderen, ed. M. Swyngedouw, J. Billiet, and B. Goeminne, 145–165. Leuven: Universitaire Pers.

Kim, N., J. Krosnick, and D. Casasanto. 2015. Moderators of candidate name-order effects in elections: An experiment. Political Psychology 36 (5): 525–542.

King, A., and A. Leigh. 2009. Are ballot order effects heterogeneous? Social Science Quarterly 90 (1): 71–87.

Koppell, J.G., and J.A. Steen. 2004. The effects of ballot position on election outcomes. Journal of Politics 66 (1): 267–281.

Lijphart, A., and R.L. Pintor. 1988. Alphabetic bias in partisan elections: Patterns of voting for the Spanish senate, 1982 and 1986. Electoral Studies 7 (3): 225–231.

Lutz, G. 2010. First come, first served: The effect of ballot position on electoral success in open ballot PR elections. Representation 46 (2): 167–181.

Maddens, B., and G.-J. Put. 2013. Office effects and campaign spending in a semi-open list PR system: The Belgian/Flemish federal and regional elections 1999–2010. Electoral Studies 32 (4): 852–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.02.008.

Maddens, B., B. Wauters, J. Noppe, and S. Fiers. 2006. Effects of campaign spending in an open list PR system: The 2003 legislative elections in Flanders/Belgium. West European Politics 29 (1): 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380500389398.

Marcinkiewicz, K. 2014. Electoral contexts that assist voter coordination: Ballot position effects in Poland. Electoral Studies 33: 322–334.

Marcinkiewicz, K., and M. Stegmaier. 2015. Ballot position effects under compulsory and optional preferential-list PR electoral systems. Political Behavior 37 (2): 465–486.

McDermott, M.L. 2009. Voting for myself: Candidate and voter group associations over time. Electoral Studies 28: 606–614.

Meredith, M., and Y. Salant. 2013. On the causes and consequences of ballot order effects. Political Behavior 35 (1): 175–197.

Miller, A.H., and O. Listhaug. 1990. Political parties and confidence in government: A comparison of Norway, Sweden and the United States. British Journal of Political Science 20 (3): 357–386.

Miller, A.H., M.P. Wattenberg, and O. Malanchuk. 1986. Schematic assessments of presidential candidates. American Political Science Review 80 (2): 521–540.

Miller, J.M., and J.A. Krosnick. 1998. The impact of candidate name order on election outcomes. Public Opinion Quarterly 62 (3): 291–330.

Petrocik, J.R. 1996. Issue ownership in presidential elections, with a 1980 case study. American Journal of Political Science 40 (3): 825–850.

Put, G.-J., and B. Maddens. 2013. The selection of candidates for eligible positions on PR lists: The Belgian/Flemish federal elections 1999–2010. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 23 (1): 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2012.743465.

Sheafer, T., and S. Tzionit. 2006. Media-political skills, candidate selection methods and electoral success. The Journal of Legislative Studies 12 (2): 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330600739447.

Tourangeau, R., M.P. Couper, and F.G. Conrad. 2013. “Up means good” the effect of screen position on evaluative ratings in web surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 77 (S1): 69–88.

Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1975. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 185 (4157): 1124–1131.

Van Biezen, I., and T. Poguntke. 2014. The decline of membership-based politics. Party Politics 20 (2): 205–216.

Van Erkel, P.F., and P. Thijssen. 2016. The first one wins: Distilling the primacy effect. Electoral Studies 44: 245–254.

Walgrave, S., and K. De Swert. 2007. Where does issue ownership come from? From the party or from the media? Issue-party identifications in Belgium, 1991-2005. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 12 (1): 37–67.

Whiteley, P.F. 2011. Is the party over? The decline of party activism and membership across the democratic world. Party Politics 17 (1): 21–44.

Funding

This work was supported by a Research Grant of the Flemish Research Foundation (FWO): Project Number G000915N entitled ‘Political gender stereotypes in a system of Proportional Representation.’ The funder was not involved in the development of the study and the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Devroe, R., Wauters, B. Does high on the ballot means highly competent? Explaining the ballot position effect in list-PR systems. Acta Polit 55, 454–471 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0124-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-018-0124-y