Abstract

Traditional theories of collective action would predict that, after a triggering event, the trajectory of a wave of protest is determined by the institutionalisation–radicalisation tandem. Based on the Spanish cycle of anti-austerity and against the political status quo protest in the shadow of the Great Recession, this article contends with this approach, as a clear trend towards radicalisation is never observed as the cycle unfolds. An alternative interpretative framework is developed to understand protest trajectories when collaborative inter-organisational strategies prevail. The eventful 15M campaign triggered in 2011 represents the most remarkable turning point in the Spanish socio-political mobilisation scene in recent years and had a transformative capacity over subsequent protest endeavours. Specifically, after the 15M campaign, the combination of downward scale shift and coalition building shaped the trajectory of mobilisation, and allowed for the peak of protest to persist until late 2013, when institutionalisation took over. Data from an original Protest Event Analysis dataset are used to illustrate the main arguments.

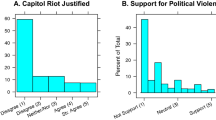

Source data retrieved from my PEA, El País (N = 2002). Own collection and elaboration

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A protest cycle or wave often consists of a set of interrelated campaigns. A protest campaign is the series of thematically interconnected interactions and public claim-making performances for a common aim (della Porta and Diani 2006, pp. 188–189).

15 M stands for 15 May 2011. Participants tend to adopt this neutral label to the detriment of other terms to refer to this campaign and its activists such as indignados (“the outraged”)—Romanos (2016).

The list of keywords—introduced separately in Spanish—was as follows: protesta, manifestación, escrache, 15M, indignados, marea, movilización, marcha, acampada, sentada, boicot. I ran a mini-test with the Spanish El Mundo to control for possible biases in the primary newspaper source, comparing 2 months, pre- and post-15M (April 2009 and November 2013). No substantial differences regarding event coverage were found—overlap between protest events in El País and El Mundo was higher than 90%.

As the printed media is a crucial arena for public claims-making, and most actors use it to make their views public, I used newspaper (daily) records. Following Beissinger (2002, p. 14), the units of analysis in my PEA, events, are defined as “contentious and potentially subversive acts that challenge normalised practices, modes of causation, or systems of authority”. No sampling strategies were implemented: information about size was coded regardless of the kind and size of the event, collecting data neither exclusively on the largest events nor on those strictly associated with the recession, austerity, labour issues and the political status quo. Following Kriesi et al. (1995), opinion and editorial sections were omitted.

Calculating the number of protesters in a given event is problematic. Quality of information reported usually depends on the newspaper source and is scant and partial. To tackle this issue, I have gathered information on the three main sources of information on the size of challengers separately (when available). These three continuous indicators are the number of participants reported by (1) the police or official authorities, (2) El País newspaper and (3) the organisers. As police records usually underestimate the number of participants and organisers overestimate them, a coefficient that measures average, over or underestimation was calculated for each variable. Weighted coefficients are extrapolated from cases with full information (N′ = 45) for all categories to those that only have partial data, and then arithmetic weighted means are calculated on the basis of the values for the (1-to-3) sources available. An additional indicator captures estimations and vague cues on event size (e.g. some hundreds, several thousands, etc.). It was transformed into a 1–10 interval-level scale following the procedures specified in the codebook for Dynamics of Collective Action (N″ = 505; see http://web.stanford.edu/group/collectiveaction/cgi-bin/drupal/node/17).

Tarrow (2011, p. 207) defines institutionalisation as “a movement away from extreme ideologies and/or the adoption of a more conventional and less disruptive forms of contention”.

Following Karapin (2007), I distinguish among (1) semi-conventional strategies (if using or promoting routine forms of participation in order to bargain and compromise with opponents), (2) mild or (3) severe disruptive strategies (if disrupting political-economic routines in non-violent ways through more moderate—e.g. rallying—or more disruptive repertories—e.g. occupations—) and (4) militant strategies (if using intimidation and coercion by threatening opponents or engaging in violence).

Protesters’ violence is a dummy that captures whether protesters resorted to violent tactics of any kind (weapons, physical, other, etc.). Coercion is measured on a 0–3 scale: (0) no known coercion, (1) low-level coercion (sporadic arrests and/or injuries, defined as less than ten), (2) substantial coercion (defined as 10–75 arrests or 10–40 injuries), (3) major violence by authorities (defined as more than 75 arrests or more than 40 injuries). Overall violence takes into account human and property damage inflicted by coercion and demonstrators’ violence. A five-point interval scale adapted from Spilerman (1976) is used—the maximum category of violence is selected provided at least two of the described items apply: (0) no violence, (1) low intensity (bottle throwing, some fighting, little property damage, crowd size < 125, arrests < 15, injuries < 8); (2) moderate violence (rock and bottle throwing, fighting, looting, serious property damage, some arson, 75–250 crowd size, 10–30 arrests; 5–15 injuries; (3) substantial violence (looting, arson and property destruction, 200–500 crowd size, 25–75 arrests, 10–40 injuries); (4) high-intensity major violence (defined as bloodshed and destruction, +400 crowd size, +65 arrests, +35 injuries). See Table 2 in “Appendix”.

The picture on repression and violence in the subsample of anti-political status quo, labour, crisis-related and anti-austerity events only do not change substantially (not reported here).

Relational mechanisms are those that “alter connections among people, groups, and interpersonal networks” (McAdam et al. 2001, p. 26).

Although downward scale shift might increase in contentious performances through direct social action and solidarity initiatives, such as cooperatives, markets, etc. (Bosi and Zamponi 2015), consistent with available literature on cycles and my PEA dataset, I emphasise the protest dimension throughout.

Note that the terms “coalitions” and “alliances” are used interchangeably throughout.

Note that joining a coalition may also engender risks and costs for organisations (e.g. loss of autonomy, potential conflict with partners, alteration of strategic choices, compromise identity, etc.), as Heaney and Rojas (2008) argue.

This bill was heavily contested by different actors on the grounds of individual schools’ loss of autonomy, change in the university access system, discrimination of minority languages, etc.

References

Accornero, Guya, and Pedro Ramos Pinto. 2015. ‘Mild Mannered’? Protest and Mobilization in Portugal under Austerity, 2010–2013. West European Politics 38 (3): 491–515.

Alimi, Eitan Y., Chares Demetriou, and Lorenzo Bosi. 2015. The Dynamics of Radicalization. A Relational and Comparative Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beissinger, Mark. 2002. Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blyth, Mark. 2013. Austerity. The history of a dangerous idea. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bosi, Lorenzo. 2016. Incorporation and Democratization. The Long-Term Process of Institutionalization of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movements. In The Consequences of Social Movements, ed. Lorenzo Bosi, Marco Giugni, and Katrin Uba, 338–360. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bosi, Lorenzo, and Lorenzo Zamponi. 2015. Direct Social Actions and Economic Crises. The Relationship Between Forms of Action and Socio-economic Context in Italy. Partecipazione e Conflitto 8 (2): 367–391.

Calvo, Kerman, and Iago Álvarez. 2015. Limitaciones y exclusiones en la institucionalización de la indignación: del 15M a Podemos. Revista Española de Sociología 24: 115–122.

Calvo, Kerman, and Martín Portos. 2018. Panic Works: the ‘Gag Law’ and the Unruly Youth in Spain. In Governing Youth Politics in the Age of Surveillance, ed. Maria T. Grasso, and Judith Bessant. London: Routledge.

della Porta, Donatella. 2008. Eventful Protest, Global Conflicts. Distinktion 17: 27–56.

della Porta, Donatella. 2015. Social Movements in Times of Austerity: Bringing Capitalism back into Protest Analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

della Porta, Donatella, and Mario Diani. 2006. Social Movements: An Introduction, 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

della Porta, Donatella and Sidney G. Tarrow. 1986. Unwanted children: Political violence and the cycle of protest in Italy, 1966-1973. European Journal of Political Research 14: 607–632.

Diani, Mario, and Maria Kousis. 2014. The Duality of Claims and Events: The Greek Campaign Against the Troika’s Memoranda and Austerity, 2010–2012. Mobilization 19 (4): 387–404.

Díez García, Rubén. 2017. The “Indignados” in Space and Time: Transnational Networks and Historical Roots. Global Society 31 (1): 43–64.

Feenstra, Ramón. 2015. Activist and Citizen Political Repertoire in Spain: A Reflection Based on Civil Society Theory and Different Logics of Political Participation. Journal of Civil Society 11 (3): 242–258.

Fernández-Albertos, José. 2015. Los votantes de Podemos. Del partido de los indignados al partido de los excluidos. Madrid: Libros La Catarata.

Fillieule, Olivier. 2013. Demobilization. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, ed. David A. Snow, Donatella della Porta, Bert Klandermans, and Doug McAdam. London: Blackwell.

Flesher Fominaya, Cristina. 2014. Social Movements and Globalization. How Protests, Occupations and Uprisings are Changing the World. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Flesher Fominaya, Cristina. 2015. Debunking Spontaneity: Spain’s 15M/Indignados as Autonomous Movement. Social Movement Studies 14 (2): 142–163.

Ganz, Marshall. 2010. Leading Change. Leadership, Organization, and Social Movements. In Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice. A Harvard Business School Centennial Colloquium, ed. Nitin Nohria, and Rakesh Khurana, 509–550. Danvers: Harvard Business School Press.

Gerhards, Jürgen, and Dieter Rucht. 1992. Mesomobilization: Organizing and Framing in two Protest Campaigns in West Germany. American Journal of Sociology 98: 555–595.

Gómez, Luis. 2013. 1.100 maneras de protestar en España. El País. http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2013/03/30/actualidad/1364669519_850037.html. Accessed 27 April 2014, published 30 March 2013.

Heaney, Michael, and Fabio Rojas. 2008. Coalition Dissolution, Mobilization, and Network Dynamics in the U.S. Antiwar Movement. Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change 28: 39–82.

Hemerijck, Anton. 2016. New EMU governance: Not (yet) ready for social investment. Institute for European Integration Research, Working Paper No. 01/2016.

Hess, David, and Brian Martin. 2006. Repression, Backfire, and the Theory of Transformative Events. Mobilization 11 (1): 249–267.

Hutter, Swen. 2014. Protest Event Analysis and its Offspring. In Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research, ed. Donatella della Porta, 335–367. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Isaac, Larry. 2010. Policing Capital: Armed Countermovement Coalitions against Labor in the Nineteenth-Century Industrial Cities. In Strategic Alliances: Coalition Building and Social Movements, ed. Nella van Dyke, and Holly J. McCammon, 22–49. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Jiménez, Manuel. 2011. La normalización de la protesta. El caso de las manifestaciones en España (1980–2008). Madrid: CIS.

Jones, Andrew W., Richard N. Hutchinson, Nella Van Dyke, Leslie Gates, and Michele Companion. 2001. Coalition Form and Mobilization Effectiveness in Local Social Movements. Sociological Spectrum 21 (2): 207–231.

Jung, Jai Kwan. 2010. Disentangling Protest Cycles: An Event History Analysis of New Social Movements in Western Europe. Mobilization 15 (1): 25–44.

Kanellopoulos, Kostas, Konstantinos Kostopoulos, Dimitris Papanikolopoulos, and Vasileios Rongas. 2016. Competing Modes of Coordination in the Greek Anti-austerity Campaign, 2010–2012. Social Movement Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2016.1153464.

Karapin, Roger. 2007. Protest Politics in Germany. Movements on the Left and the Right since the 1960s. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Koopmans, Ruud. 2004. Protest in Time and Space: The Evolution of Waves of Contention. In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, ed. David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi, 19–46. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, Ruud Koopmans, Jan W. Duyvendak, and Marco Giugni. 1995. New Social Movements in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. London: UCL Press.

Martí i Puig, Salvador. 2012. 15M: The Indignados. In The Occupy Handbook, ed. Janet Bryne, 209–217. New York: Back Bay Books.

Martín, Irene. 2015. Podemos y otros modelos de partido-movimiento. Revista Española de Sociología 24: 107–114.

Martín García, Óscar. 2014. Soft Repression and the Current Wave of Social Mobilizations in Spain. Social Movement Studies 13 (2): 303–308.

McAdam, Doug, and William H. Sewell Jr. 2001. Temporality in the Study of Social Movements and Revolutions. In Silence and Voice in the Study of Contentious Politics, ed. Ronald R. Aminzade, Jack A. Goldstone, Doug McAdam, Elizabeth J. Perry, William H. Sewell Jr., Sidney G. Tarrow, and Charles Tilly, 89–125. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McAdam, Doug, Sidney G. Tarrow, and Charles Tilly. 2001. Dynamics of Contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Meyer, Rachel, and Howard Kimeldorf. 2015. Eventful Subjectivity: The Experiential Sources of Solidarity. Journal of Historical Sociology 28 (4): 429–457.

Miley, T.Jeffrey. 2016. Austerity Politics and Constitutional Crisis in Spain. European Politics and Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/23745118.2016.1237700.

Monterde, Arnau, Antonio Calleja-López, Miguel Aguilera, Xabier E. Barandiaran, and John Postill. 2015. Multitudinous Identities: a Qualitative and Network Analysis of the 15M Collective Identity. Information, Communication & Society 18 (8): 930–950.

Perugorría, Ignacia, and Benjamín Tejerina. 2013. Politics of the Encounter: Cognition, Emotions, and Networks in the Spanish 15-M. Current Sociology 61: 424–442.

Portos, Martín. 2016a. Taking to the Streets in the Context of Austerity: A Chronology of the Cycle of Protests in Spain, 2007–2015. Partecipazione e Conflitto 9 (1): 181–210.

Portos, Martín. 2016b. Movilización social en tiempos de recesión: un Análisis de Eventos de Protesta en España, 2007-2015. Revista Española de Ciencia Política 41: 137–156.

Portos, Martín, and Juan Masullo. 2017. Voicing Outrage Unevenly. Democratic Dissatisfaction, Non-participation and Frequencies of Participation in the 15-M Campaign. Mobilization 22 (2): 201–222.

Romanos, Eduardo. 2014. Evictions, Petitions and Escraches: Contentious Housing in Austerity Spain. Social Movement Studies 13 (2): 296–302.

Romanos, Eduardo. 2016. Late Neoliberalism and Its Indignados: Contention in Austerity Spain. In Late Neoliberalism and Its Discontents in the Economic Crisis. Comparing Social Movements in the European Periphery, ed. Donatella Della Porta, Massimiliano Andretta, Tiago Fernandes, Francis O’Connor, Eduardo Romanos, and Markos Vogiatzoglou. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sampedro, Víctor, and Josep Lobera. 2014. The Spanish 15M Movement: A Consensual Dissent? Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 15 (1–2): 61–80.

Sewell Jr., William H. 1996. Three Temporalities: Toward an Eventful Sociology. In The Historic Turn in the Human Sciences, ed. Terence J. McDonald, 245–280. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Spilerman, Seymour. 1976. Structural Characteristics of Cities and the Severity of Racial Disorders. American Sociological Review 41 (5): 771–793.

Staggenborg, Suzanne. 1986. Coalition Work in the Pro-Choice movement: Organizational and Environmental Opportunities and Obstacles. Social Problems 33: 374–390.

Tarrow, Sidney G. 1989. Democracy and Disorder: Protest and Politics in Italy, 1965–1975. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tarrow, Sidney G. 1993. Cycles of Collective Action: Between Moments of Madness and the Repertoire of Contention. Social Science History 17 (2): 281–307.

Tarrow, Sidney G. 2011. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Dyke, Nella, and Holly J. McCammon (eds.). 2010. Strategic Alliances. Coalition Building and Social Movements. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Viejo, Raimundo. 2012. Indignación: Política de movimiento, nueva ola de movilizaciones y crisis de representación. In La actuación del legislativo en los tiempos de crisis. México y España comparados, ed. Fermín E. Rivas, María A. Mascott, and Efrén Arellano, 123–156. Mexico: CESOP.

Zamponi, Lorenzo, and Joseba Fernández. 2017. Dissenting Youth: How Student and Youth Struggles Helped Shape Anti-austerity Mobilisations in Southern Europe. Social Movement Studies 16 (1): 64–81.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Portos, M. Keeping dissent alive under the Great Recession: no-radicalisation and protest in Spain after the eventful 15M/indignados campaign. Acta Polit 54, 45–74 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-017-0074-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-017-0074-9