Abstract

We posit that international business and the emergence and spread of communicable diseases are intrinsically connected. To support our arguments, we first start with a historical timeline that traces the connections between international business and communicable diseases back to the sixth century. Second, following the epidemiology of communicable diseases, we identify two crucial transitions related to international business: the emergence of epidemics within a host country and the shift from epidemics to global pandemics. Third, we highlight international business contextual factors (host country regulatory quality, urbanization, trade barriers, global migration) and multinationals’ activities (foreign direct investment, corporate political activity, global supply chain management, international travel) that could accelerate each transition. Finally, building on public health insights, we suggest research implications for business scholars on how to integrate human health challenges into their studies and practical implications for global managers on how to help prevent the emergence and spread of communicable diseases.

Résumé

Nous postulons que les affaires internationales et l'émergence et la propagation des maladies transmissibles sont intrinsèquement liées. Afin d’étayer nos arguments, nous commençons par une chronologie historique qui retrace les liens entre les affaires internationales et les maladies transmissibles jusqu'au sixième siècle. Deuxièmement, en suivant l'épidémiologie des maladies transmissibles, nous identifions deux transitions cruciales liées aux affaires internationales: l'émergence des épidémies dans un pays d’accueil et le passage des épidémies aux pandémies mondiales. Troisièmement, nous mettons en lumière les facteurs contextuels des affaires internationales (qualité de la réglementation du pays d'accueil, urbanisation, barrières commerciales, migration au niveau mondial) et les activités des multinationales (investissement direct à l’étranger, activité politique des entreprises, gestion de la chaîne d'approvisionnement mondiale, voyages internationaux) qui pourraient accélérer chaque transition. Enfin, nous appuyant sur la littérature de la santé publique, nous suggérons, d’une part, des implications de recherche pour les chercheurs en management sur la manière d'intégrer des défis liés à la santé humaine dans leurs travaux et, d’autre part, des implications pratiques pour les managers internationaux sur la manière d'aider à prévenir l'émergence et la propagation des maladies transmissibles.

Resumen

Planteamos que los negocios internacionales y el surgimiento y propagación de enfermedades transmisibles están conectados intrínsecamente. Para apoyar nuestros argumentos, primero comenzamos con un cuadro cronológico que rastrea las conexiones entre negocios internacionales y enfermedades transmisibles hasta el siglo VI. Segundo, siguiendo la epidemiologia de las enfermedades transmisibles, identificamos dos transiciones cruciales relacionados con los negocios internacionales: el surgimiento de epidemia en un país anfitrión y el cambio de epidemia a pandemia global. Tercero, resaltamos los factores contextuales de negocios internacionales (calidad regulatoria del país anfitrión, urbanización, barreras comerciales, migración global) y las actividades de las multinacionales (inversión extranjera directa, actividad política corporativa, gestión de la cadena de abastecimiento, viajes internacionales) que podrían acelerar cada transición. Finalmente, sobre la base de los aportes de la salud pública, sugerimos implicaciones de investigación para académicos de negocios internacionales sobre cómo integrar los retos de la salud pública en sus estudios y las repercusiones prácticas para los gerentes globales sobre cómo ayudar a prevenir el surgimiento y propagación de enfermedades transmisibles.

Resumo

Postulamos que negócios internacionais e o surgimento e disseminação de doenças transmissíveis estão intrinsecamente conectados. Para apoiar nossos argumentos, começamos com uma linha do tempo histórica que traça as conexões entre negócios internacionais e doenças transmissíveis até o século VI. Em segundo lugar, seguindo a epidemiologia de doenças transmissíveis, identificamos duas transições cruciais relacionadas a negócios internacionais: o surgimento de epidemias em um país anfitrião e a mudança de epidemias para pandemias globais. Em terceiro lugar, destacamos fatores contextuais de negócios internacionais (qualidade regulatória do país anfitrião, urbanização, barreiras comerciais, migração global) e atividades de multinacionais (investimento estrangeiro direto, atividade política corporativa, gestão da cadeia de suprimentos global, viagens internacionais) que poderiam acelerar cada transição. Por fim, com base em insights de saúde pública, sugerimos implicações de pesquisa para acadêmicos de negócios sobre como integrar desafios de saúde humana em seus estudos e implicações práticas para gerentes globais sobre como ajudar a prevenir o surgimento e a disseminação de doenças transmissíveis.

摘要

我们认为, 国际商务与传染病的出现与传播有着内在的联系。为了支持我们的论点, 我们的研究首先从一个将国际商务与传染病之间的联系追溯到六世纪的历史时间线开始。其次, 根据传染病的流行病学, 我们确定了与国际商务相关的两个关键转型: 东道国内部流行病的出现以及流行病向全球流行病的转型。第三, 我们强调了可以加速每次转型的国际商务的情境因素 (东道国监管质量、城市化、贸易壁垒、全球移民) 和跨国公司的活动 (外国直接投资、企业政治活动、全球供应链管理、国际旅行) 。最后, 基于公共卫生见解, 我们提出了关于商业学者对如何将人类健康挑战整合到他们研究中的研究启示以及关于全球管理者如何帮助预防传染病的出现与传播的实际启示。

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

It is remarkable that the tiny SARS-CoV-2 virus – severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus – took such an enormous toll on the human race. The lack of preparedness of society and business came with a high price tag. Furthermore, given dissimilar social conditions and political institutions promoting human health, the burden of COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, affected nations very differently (Bapuji, de Bakker, Brown, Higgins, Rehbein, & Spicer, 2020; Bapuji, Patel, Ertug, & Allen, 2020). Yet, despite the latent linkage between international business and health challenges, only recently have business scholars started to focus their attention on this nexus (Ahen, 2019; Montiel, Cuervo-Cazurra, Park, Antolín-López, & Husted, 2021). In fact, there is limited literature in international business on the topic, despite growing scholarship in the field of public health,1 which traces the origins and spread of many communicable diseases to processes and activities related to international business (Baker et al., 2021; Harrison, 2012; King, Peckham, Waage, Brownlie, & Woolhouse, 2006; Labonté, Blouin, & Forman, 2009; Morse, Mazet, Woolhouse, Parrish, Carroll, & Karesh, 2012; Rohr, Barrett, Civitello, Craft, Delius, & DeLeo, 2019; Wilson, 2003; Wu, Perrings, Kinzig, Collins, Minteer, & Daszak, 2017). In the public health literature, there is an increasing understanding that communicable diseases have environmental origins driven by social and economic pressures with roots in globalization (Frenk, Gómez-Dantés, & Moon, 2014; Labonté, Mohindra, & Schrecker, 2011; Wu et al., 2017), of which multinationals are one of the principal agents (Barnett & Whiteside, 2002; Saker, Lee, Cannito, Gilmore, & Campbell-Lendrum, 2004).

Although insightful, public health research tends to over-emphasize the negative aspects of large corporations in global health, while overlooking the mechanisms through which the contextual factors of international business, as well as the operations and strategies of multinationals, are connected to health outcomes. The absence of an international business perspective in research on the international business–communicable disease nexus has meant that public health scholarship has proposed suggestions for public policy without much regard to business policy. Furthermore, public health scholars perceive international business research as too accommodating of the role of many multinationals in extracting rents from host countries (Baum & Anaf, 2015; Freudenberg, 2014). That said, international business scholars need to give public health scholars credit, since they provide different and fresh perspectives on the connections between international business and communicable diseases worldwide.

In this piece, we take a glimpse at recent business and public health research examining the role of international business as an agent of communicable disease transmission. We argue that international business often fosters the emergence and spread of communicable diseases across the globe. To support our argument, we provide historical and contemporary evidence linking the two. We begin by documenting the historical connections between international business and communicable diseases. Then, we organize contemporary evidence in terms of four contextual factors of international business (host-country regulatory quality, urbanization, trade barriers, global migration) and four activities of multinationals (foreign direct investment, corporate political activity, global supply chain management, international travel) that may facilitate the emergence of a communicable-disease epidemic and its progression into a pandemic. Then, we build on public health insights to offer a research agenda that connects international business research with communicable diseases. Finally, we conclude with practical implications for how managers of multinationals can contribute to preventing the emergence and spread of communicable-disease epidemics and pandemics, and to tackling other health challenges.

BACKGROUND AND A BRIEF HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND COMMUNICABLE DISEASES

From the first COVID-19 patient in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, through the subsequent outbreak in the region until January 2022, there were more than 374 million recorded cases and 5.6 million recorded deaths from COVID-19 around the world (Johns Hopkins University & Medicine, 2022). Given globalization and urbanization, Wuhan provided the conditions for a perfect storm leading to the emergence and spread of COVID-19. With over ten million people (United Nations, 2018), the city’s high population density contributed to the initial appearance of the virus. Increasing connectedness between Wuhan and the rest of the world facilitated the dissemination of the virus. Wuhan’s industrial and transport hub status attracted global travel and commercial activities. For instance, Wuhan Tianhe International Airport offered flights to 101 international destinations in 17 countries as of May 2020 (FlightConnections, 2020). The city also achieved economic growth mainly based on providing support for multinationals, such that 230 of the Fortune Global 500 firms had invested in the city as of 2020 (BBC News, 2020). To give just one example, more than 100 French multinationals actively engaged in Wuhan’s economic growth through foreign direct investment – including major automakers like Groupe PSA (Hu & Zhou, 2019). Thus, it becomes critical for international business scholars to better understand the mechanisms through which international business affects the emergence and spread of communicable diseases and to help multinationals prepare for future pandemics.

At this point, a definition of communicable disease is warranted. Communicable diseases are those diseases “caused by microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, parasites and fungi that can be spread, directly or indirectly, from one person to another” (World Health Organization, 2020a). Of particular interest are emerging infectious diseases, which are “infections that have newly appeared in a population or have existed, but are rapidly increasing in incidence or geographic range” (Morse, 1995: 7). The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) use a 20-year period to distinguish emerging infectious diseases from other communicable diseases (CDC, 2018). Recent examples of emerging infectious diseases include ebola, HIV/AIDS, influenza, Lyme disease, Zika virus, and SARS coronavirus. According to the CDC (2021), three out of every four new or emerging infectious diseases are zoonoses – diseases or infections that can be transmitted from animals to humans. Emerging infectious diseases are especially likely to appear under certain environmental conditions, such as climate change and deforestation (Daszak, Cunningham, & Hyatt, 2000; Jones, Patel, Levy, Storeygard, Balk, & Gittleman, 2008) and socio-economic and political conditions, including poverty, social inequality, the incapacity of political instruments, and international travel and commerce (Morens, Folkers, & Fauci, 2004).

Interestingly, the link between international business and trade to the spread of communicable disease is not recent. A sense of the historical relationship between international business and some relevant past pandemics is provided in Table 1. As early as the year 541, the earliest form of international business – trade – was implicated in the spread of communicable diseases. In this case, the disease was the same bubonic plague (Yersinia pestis) that was to wreak havoc in Europe 800 years later (Harrison, 2012; Huremović, 2019; Piret & Boivin, 2021). On that later occasion, one-third of Europe’s population died. Most explanations point to China as the source of the plague, which spread from there to the Black Sea. The specific path is unknown, but trade routes along the Silk Road are likely. From the Black Sea, the spread of the plague to Europe can be traced more precisely. It appears to have traveled to seaports and then along major rivers like the Rhine and Loire (Harrison, 2012; Huremović, 2019; Piret & Boivin, 2021).

Transatlantic Encounters and Trade Intensification

Clearly, international trade routes can have unintended consequences. One of the unintended consequences of the Spanish conquest of the Americas was its role in the spread of smallpox. Some indigenous peoples saw their populations reduced by 90% or more as a result. Although it would be an exaggeration to call the Spanish conquest a form of international business, once smallpox arrived in the Western hemisphere, it spread along the trade routes of the indigenous peoples south to Bolivia and north to territories which are now part of the United States (Harrison, 2012). The earliest flu pandemics also spread along trade routes; the 1580 pandemic appears to be the first that can be attributed to the flu with reasonable certainty (Taubenberger & Morens, 2009). It began in Asia and spread to Europe along trade routes (Tognotti, 2009). In Asia, it was known as the “wind illness” because it spread with such rapidity (Tognotti, 2009). It reached Africa and may even have arrived in Chile in 1617 by way of Spain (Taubenberger & Morens, 2009).

Yellow fever arrived in the Western hemisphere from Africa through mosquitoes on slave ships, considered a form of international trade, although one of its darkest forms. The spread of yellow fever along the Eastern coastal ports in the 1690s – Boston, Philadelphia, Charleston – was facilitated in the southeast by deforestation to make way for the sugar plantations, which then exported their product to European capitals. Deforestation eliminated the habitats of animals that normally would have fed on the mosquitos and other insects which carried the yellow fever virus (Harrison, 2012).

The Twentieth Century and Beyond

The pneumonic plague of Manchuria of 1910–1911 was derived from the same Yersinia pestis which caused the bubonic plague. The main difference between the two is where they are located in the human body, with the pneumonic plague affecting the lungs and the bubonic plague, the lymphatic system. The Manchurian plague originated with the local trade in marmot furs and affected commerce with China, Russia, and Japan. Russia and China eventually banned Manchurian fur in 1911. Sixty thousand Manchurians lost their lives and lost trade amounted to roughly US$100 million (Harrison, 2012; Piret & Boivin, 2021). A remarkable side effect of the plague was the unusual international collaboration between Chinese and Russian physicians to fight it (Gamsa, 2006).

Although it was primarily the movement of troops and armor across the oceans during World War I that facilitated its spread (Flecknoe, Charles Wakefield, & Simmons, 2018), the Spanish flu provides a classic case of responding to pandemics with increased tariffs and non-tariff barriers which impede international commerce (Boberg-Fazlic, Lampe, Pedersen, & Sharp, 2021). Isolating the effect of the war on tariffs, Boberg-Fazlic et al. (2021) found that a one standard deviation increase in excess deaths during the Spanish flu epidemic resulted in an increase of one-third of a standard deviation in tariffs. So, although the Spanish flu was mainly spread by the war, the ensuing pandemic clearly had substantial implications for international business by spurring protectionist trade policies.

The SARS epidemic originated in the Chinese province of Guangdong in November 2002, and quickly spread to Hong Kong in February 2003 (Cherry & Krogstad, 2004). Bats and palm civets were the transmission vectors (Wang, Shi, Zhang, Field, Daszak, & Eaton, 2006). The consequences for Hong Kong and the nearby province were severe. Travel to Hong Kong was significantly curtailed (The & Rubin, 2009), and the region was forced to pull out of an international trade fair for watches in Switzerland. The cost of the ban on Hong Kong’s participation was estimated to be US$1.8 billion (Harrison, 2012). Overall, international travel and tourism to Asia dropped by around 10% (Harrison, 2012).

The story of the current COVID-19 pandemic is still unfolding. Its origins in China are being studied, but likely point to zoonosis from bats to a human population near Wuhan. There seems to be a cocktail of influences behind this spread, including international business connections, international travel, and deforestation (McMahon, 2020). The economic cost of the COVID-19 virus is estimated to have reached US$16 trillion in the United States (Cutler & Summers, 2020) and at least US$28 trillion around the world (Gopinath, 2020). Yet, despite the cost of COVID-19, World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has warned that COVID-19 will not be the last pandemic, nor the most virulent one (World Health Organization, 2020b).

This brief review shows that international business in various forms has been implicated in epidemics and pandemics around the world over the last 1,500 years. Some common themes bind these together. In most cases, trade is a common factor driving the spread of diseases. Vectors of contagion may be the human beings that trade or the animals, such as fleas or mosquitos, that travel with them. As a whole, international business is implicated, not just in terms of trade but also via tourism and business travel, as well as indirectly through deforestation to clear land for products manufactured or grown for international sales in an increasingly globalized world. Finally, both yesterday and today, governments worldwide have responded to pandemics with quarantines, lockdowns, and border controls (Piret & Boivin, 2021). Thus, international business is not only deeply involved in the spread of pathogens but also affected by government responses through pandemic controls, especially trade barriers.

INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS AND COMMUNICABLE DISEASES TODAY

A recent JIBS Perspective urged international business scholars to research the link between grand challenges and international business via an interdisciplinary approach (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017). Yet, despite a potential link between international business activities and communicable diseases, we rarely observe international business studies addressing this particular relationship, other than studies examining occupational health and safety (Arnold & Bowie, 2003, 2007; Collings, Scullion, & Morley, 2007; Himmelberger & Brown, 1995) or other issues where health directly affects the financial bottom line, including accessibility to medicines and healthcare services in the global pharmaceutical industry (Flanagan & Whiteman, 2007; Ghauri & Rao, 2009; Leisinger, 2005, 2009), multinationals’ activities designed to enhance local community health in poor host countries (Gifford & Kestler, 2008; Gold, Hahn, & Seuring, 2013; Van Cranenburgh & Arenas, 2014), the role of food and tobacco multinationals in addressing noncommunicable diseases (Gertner & Rifkin, 2018; Mukherjee & Ekanayake, 2009; Palazzo & Richter, 2005; Tempels, Blok, & Verweij, 2020), and product safety assurance in global value chains (Bapuji & Beamish, 2019; Scruggs & Van Buren, 2016). Coincidentally, public health researchers have already engaged in these conversations, mostly questioning multinationals’ role in global health from a critical perspective (Baum, Sanders, Fisher, Anaf, Freudenberg, & Friel, 2016; Baum & Anaf, 2015; Freudenberg, 2014; Kadandale, Marten, & Smith, 2019; Kickbusch, Allen, & Franz, 2016; Moodie, Stuckler, Monteiro, Sheron, Neal, & Thamarangsi, 2013; Müller et al., 2021; Stuckler, McKee, Ebrahim, & Basu, 2012). It is time to start a consistent international business-health research agenda that builds upon existing literature, theories, and models from international business and public health.

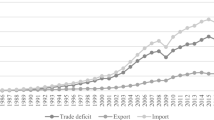

To build bridges between international business and public health research, and to suggest an avenue for future research and practice, we combine insights from both fields to clarify the connections between international business and communicable diseases as a critical health grand challenge. Hence, we propose an integrative framework in Figure 1 that draws from existing international business and public health concepts. From public health, we build on the phases of a pandemic (WHO Global Influenza Programme & World Health Organization, 2009) to display a communicable-disease pandemic process, starting with few human infections, followed by an epidemic and its progression to a pandemic. Then, we highlight international business contextual factors and multinationals’ activities that can contribute to the development of these transitions.

The Emergence of Epidemics within a Host Country

An epidemic refers to “the occurrence in a community or a region of cases of an illness, specific health-related behavior or other health-related events clearly in excess of normal expectancy” (World Health Organization, 2007: v). Although epidemics – and pandemics – can apply to noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes, most cancers, and chronic respiratory diseases (Allen, 2017), we specifically focus on communicable diseases; an epidemic is likely to emerge when the spread of communicable diseases develops from a few human infections to widespread localized infections (O’Brien, 2013). We start by highlighting two international business contextual factors that can contribute to the emergence of an epidemic within a host country – host-country regulatory quality and urbanization. We then look at two activities undertaken by multinationals that can foster the emergence of an epidemic – foreign direct investment and corporate political activity. We consider these four dimensions closely connected to dynamics of international business and multinationals’ activities in the host country where they operate, thereby promoting the emergence of a communicable diseases epidemic.

Host country regulatory quality

A host country’s regulatory quality affects and can be affected by multinationals’ behavior (Doh, Rodrigues, Saka-Helmhout, & Makhija, 2017; Meyer, 2004; Xu, Hitt, Brock, Pisano, & Huang, 2021). In countries with low regulatory quality where local regulations are lax or not enforced, multinationals may engage in practices that create favorable conditions for the emergence of a communicable-disease epidemic. We explain this relationship by focusing on three arenas of regulation: public health, nutrition, and environmental regulations.

First, poor public health regulations of the host country – regarding communicable disease prevention, detection, and containment – have the potential to facilitate the emergence of epidemics. Examples of such regulations include mask-wearing, infectious disease testing, contact tracing, and quarantine policies designed to prevent and control the spread of communicable diseases within the country (Escandón, Rasmussen, Bogoch, Murray, Escandón, Popescu, & Kindrachuk, 2021). Multinationals could take advantage of these regulatory voids to reduce operational costs by not strictly implementing communicable disease prevention measures in their host-country operations, thus contributing to the emergence of epidemics. Second, weak nutrition regulations can fail to protect a host-country’s citizens from unhealthy food commodities and allow multinationals to tap into processing, marketing, and retailing of such commodities (de Lacy-Vawdon & Livingstone, 2020; Labonté et al., 2011). When the population lacks access to healthy dietary products or adequate nutritional information, they are more likely to suffer from nutritional deficiencies, weakening their immune system and ability to fight infection from communicable diseases (Brundtland, 2000). Third, a host-country’s weak environmental regulations may create pollution havens, which attract the most polluting activities of multinationals, given the low likelihood of being sanctioned, thereby degrading the host-country’s natural environment (Berry, Kaul, & Lee, 2021; Jorgenson, 2009; Li & Zhou, 2017). Such negative impacts on the natural environment can foster epidemics, because poor water, sanitation, and air quality contribute to the transmission and spread of communicable diseases (World Health Organization, 2021).

For example, according to the New York Times, Coca-Cola Femsa extracted more than 300,000 gallons of water a day in a southern Mexican state, which intensified chronic water shortages for the local indigenous population (Lopez & Jacobs, 2018). In turn, the water shortages have made soft drinks more available and affordable than potable water in those communities, possibly exacerbating noncommunicable diseases such as obesity and diabetes among the population. Noncommunicable diseases exacerbate the severity of communicable diseases, as was demonstrated in a recent study on the distribution of comorbidities among adult tuberculosis patients in Chiapas, which confirmed that the most prevalent comorbidity2 was diabetes (Rashak et al., 2019).

Urbanization

Public health scholars have linked the increased urbanization of the last decades to the rapid spread of diseases, and point to multinationals as the primary driver, arguing they are partially responsible for the increase of communicable diseases (Barnett & Whiteside, 2002; Saker et al., 2004; Washer, 2010). In host countries, highly urbanized areas and mega-cities attract multinationals that benefit from agglomeration, including access to infrastructure, affordable workforce, and proximity to transportation hubs (Estrin, Nielsen, & Nielsen, 2017; Lorenzen, Mudambi, & Schotter, 2020; Yusuf & Nabeshima, 2005). These benefits help multinationals lower entry costs and risks (Goerzen, Asmussen, & Nielsen, 2013; Zhu, Aranda Larrey, & Santos, 2015). As multinationals move into highly urbanized areas, an increasing concentration of multinationals in a given urban area makes it appealing for the rural population to move into the city searching for jobs and a better life (Estrin, Nielsen, & Nielsen, 2017). The ever-growing number of people moving from the countryside into crowded cities and high-density urban slums leads to overcrowding and a lack of essential sanitation services (Washer, 2010). Overcrowding, added to poor urban planning, can foster epidemics (Alirol, Getaz, Stoll, Chappuis, & Loutan, 2011; Krämer, Kretzschmar, & Krickeberg, 2010).

In addition, rural migrants tend to adopt city-based lifestyles and use more resources once they become urbanites. The migration-led growth in urban areas requires cities to expand into surrounding areas to build new infrastructures, such as roads, water, sanitation, and energy services (Washer, 2010). As the city limits extend into undeveloped land and forests (van Vliet, 2019; Wu, Li, & Yu, 2016), the surrounding ecosystems are disrupted, stressing its wildlife, and increasing the susceptibility of animals to infection, and hence the likelihood of the transmission of viruses from animals to people (Daszak et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2017).

The 2003 SARS epidemic demonstrates how urbanization influences the emergence and spread of communicable-disease epidemics. Agricultural drivers, anthropogenic influences, and shifting human and animal population dynamics associated with urbanization played a role in its emergence (Reyes, Ahn, Thurber, & Burke, 2013). SARS then spread rapidly within provinces and newly urbanized cities in mainland China, infecting approximately 7,429 people and killing 685 others (Ruan & Zeng, 2008), representing over 90% of global cases and over 88% of deaths.

Foreign direct investment

The relationship between foreign direct investment and a host-country’s population health has drawn the attention of public health and development studies scholars (Alsan, Bloom, & Canning, 2006; Burns, Jones, Goryakin, & Suhrcke, 2017; Ghosh & Renna, 2015; Jorgenson, 2007, 2009; Labonté, 2019; Nagel, Herzer, & Nunnenkamp, 2015). One main motive for companies to invest in foreign countries is to access various resources for their global operations (Dunning, 1993; Makino, Lau, & Yeh, 2002; Zhu et al., 2015). We identify two types of resource-seeking foreign direct investment activities – low-cost labor and natural resources – which can foster the emergence of a communicable-disease epidemic in host countries.

First, multinationals frequently engage in foreign direct investment to access cheap labor in the so-called “low-wage havens” (Mani & Wheeler, 1998), thereby lowering operational costs and enabling them to remain competitive in international markets. Multinationals from developed countries have traditionally lowered their production costs by locating manufacturing facilities in low-wage developing countries (Lorenzen et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2015). The local effects of this downward pressure across multinationals’ value chains in host countries have led to low wages and unsafe and unhealthy working conditions – in so-called sweatshops (Arnold & Bowie, 2003, 2007) – which tend to increase human contact in crowded and unsanitary working spaces, creating the perfect storm for the rise of epidemics (Barnett & Whiteside, 2002).

Second, multinationals can also engage in foreign direct investment activities to access raw materials in host countries rich in natural resources (Smith, 2015). Natural resource-seeking investments, such as mining and logging, may deteriorate the host-country’s natural environment (Bird, 2016; Wegenast & Beck, 2020; Yakovleva & Vazquez-Brust, 2018). When companies destroy forests to grow crops, mine, or build infrastructure, they are likely to weaken animals’ immunological systems, which increases the likelihood of zoonosis and thereby potential communicable-disease outbreaks within the country (Carrington, 2020; Rohr et al., 2019; World Wide Fund For Nature, 2020).

The case of the Nipah virus, a zoonotic virus that appeared in Malaysia and Singapore in 1999 (CDC, 2020a), may be traced back to foreign direct investment-induced deforestation in Indonesia. According to the non-profit organization, GRAIN (2007), the American multinational Cargill launched its first palm-oil plantations in Sumatra, Indonesia, in 1997, and the Malaysian multinational Kuok Group established the country’s largest sugar plantation in Indonesia in the 1970s, both likely having accelerated the country’s deforestation. It is believed that such deforestation in the Indonesian forest decimated fruit trees that local bats feed on, driving the bats’ migration to neighboring Malaysia, where pigs on commercial farms were infected with the Nipah virus, following which pig farmers contracted the disease (Kahn, 2011).

Corporate political activity

Corporate political activities refer to business efforts to influence government regulations and policies for their benefit (Getz, 1997). As many multinationals follow a system based on economic growth and profit maximization (Buckley & Casson, 1998; Freudenberg, 2014; Young & Makhija, 2014), they may engage in activities – e.g., lobbying, political contributions, and informal connections to local elites – that could weaken the host-country’s regulations that are supposed to protect their population’s health and mitigate the emergence of epidemics (Harvey, 2021). We discuss the connections between multinationals’ political activities in the host countries and epidemics in three industry groupings: unhealthy commodity, extractive, and pharmaceutical industries.

First, multinational political activities in unhealthy commodity industries, such as tobacco, alcohol, and processed food, have received particular attention due to the harmful nature of many of their products (Clapp & Scrinis, 2017; Freudenberg, 2014; Moodie et al., 2013). Some multinationals in these industries seek to shape policies and influence regulations for their financial gains at the expense of the local population’s health (McKee & Stuckler, 2018; Mialon, Swinburn, Allender, & Sacks, 2017). Smoking and eating unhealthy foods are risk factors for noncommunicable diseases, such as cancer and obesity, which could also lead to impaired immune responses (Dobner & Kaser, 2018), making the local population more vulnerable to communicable diseases (Mendenhall, Kohrt, Norris, Ndetei, & Prabhakaran, 2017).

Second, there is some evidence that multinationals in extractive industries, like oil, gas, and mining, weaken the host-country’s health and environmental regulations to reduce the costs of natural-resource extraction (Elum, Mopipi, & Henri-Ukoha, 2016). These extractive operations often stress ecosystems by polluting air, water, and soil, and clearing out forests (Edwards, Sloan, Weng, Dirks, Sayer, & Laurance, 2014; Yakovleva & Vazquez-Brust, 2018), which increases the potential emergence of epidemics (O’Brien, 2013).

Finally, big pharmaceutical multinationals may obstruct equitable access to drugs to treat communicable-disease infection in host countries by lobbying host governments for intellectual property protections (Grover, Citro, Mankad, & Lander, 2012). For example, pharmaceutical multinationals can go on a lobbying campaign against host-country governments to block laws that allow domestic generic producers to produce low-price copies of patented drugs on HIV/AIDS held by the multinationals (Kishore, Kolappa, Jarvis, Park, Belt, & Balasubramaniam, 2015). Such lobbying practices may increase the price of medications for communicable diseases and weaken the host-country’s capacity to control and prevent epidemics.

The case of ExxonMobil is illustrative of how a multinational’s corporate political activity could facilitate the emergence of epidemics. According to the Open Society Justice Initiative (2010), the oil multinational partially relied on the highly corrupt political environment in Equatorial Guinea to expand its operations and obtain natural resources, the benefits of which accrued, not to the local people, but to the country’s ruling elite through corrupt contracts and illicit payments from the oil industry. Shah (2013) claims that the company contributed to weakening the government’s capacity to effectively contain malaria in the country by funding the country’s dictator and senior officials through bribery.

From Epidemics to Global Pandemics

A pandemic is defined as “an epidemic occurring worldwide or over a wide area crossing international boundaries, and affecting a large number of people” (World Health Organization, 2007: v). A communicable-disease epidemic is declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization if the disease cannot be contained in the region where it originated, and begins to spread across multiple countries. We identify two international business contextual factors (trade barriers, global migration) and two activities of multinationals (global supply chain management, international travel) that may trigger a communicable-disease pandemic. We consider that these four factors are likely to facilitate the evolution of a localized epidemic into a global pandemic.

Trade barriers

The growing number of multilateral, bilateral, and regional trade agreements has accelerated global trade liberalization by lowering tariffs and non-tariff barriers (Bagwell & Staiger, 2004). Removing trade barriers generally facilitates international trade (Baier & Bergstrand, 2007; Kohl, Brakman, & Garretsen, 2016; Rose, 2004; Subramanian & Wei, 2007), which in turn could lead to a global proliferation of communicable diseases affecting humans, animals, and plants (Priyadarsini, Suresh, & Huisingh, 2020; Saker et al., 2004; Smith, 2006). Increased international trade increases the speed of the translocation of viruses across geographical and ecological boundaries, which ordinarily constrain their spread, thus increasing person-to-person transmission and large-scale spread (Morse et al., 2012). Hence, non-tariff trade barriers, such as sanitary and phytosanitary measures (World Trade Organization, 1998) and meat and poultry processing standards for the reduction in pathogen levels (Todd, 2004), as well as quarantines and travel restrictions, are often established as a means to slow the spread of communicable diseases across international borders.

However, non-tariff trade barriers can also have the opposite effect by increasing the risk of pandemics, because they can restrict trade in supplies needed to fight communicable diseases. Examples include export restrictions on medical supplies, personal protective equipment, and vaccines. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that many countries still apply non-tariff trade barriers that increase prices and limit the availability of health-related essentials, such as pharmaceuticals, vaccines, and medical equipment (Baldwin & Evenett, 2020; Evenett, 2020). During the first months of the COVID-19 outbreak, China hoarded –95 masks even though their manufacturer, 3M, had a plant in China (Handfield, Graham, & Burns, 2020). Seventeen countries, accounting for five percent of traded calories, restricted exports of staple foods to protect food supplies during the pandemic (Laborde Debucquet, Mamun, & Parent, 2020). Kazakhstan, Russia, and Vietnam reduced exports of traded calories by almost 50 percent or more because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Laborde Debucquet et al., 2020), while Kazakhstan banned wheat exports entirely (Laborde Debucquet et al., 2020). Thus, trade barriers may make it hard to prevent pandemics by magnifying supply chain issues, such as the lack of medical supplies and inefficient distribution that reduce international coordination and increase production problems in global values (Baldwin & Evenett, 2020; Kerr, 2020).

Global migration

In general, migration has been historically linked to the spread and growth of epidemics (Apostolopoulos & Sönmez, 2007; Gushulak & MacPherson, 2004; Labonté & Ruckert, 2019). Social, economic, political, and environmental factors push people to migrate from their home country to other regions where they expect to find better living and working conditions (Barnard, Deeds, Mudambi, & Vaaler, 2019; Reade, McKenna, & Oetzel, 2019). All forms of global migration – economic, labor, political, environmental, and climate – can bring people from different disease-endemic geographical regions to new, sometimes high-density regions, where more economic opportunities exist (Saker et al., 2004). When people move to a new country, they may create the perfect breeding ground for communicable-disease pandemics, because both migrants and host population groups belong to different disease environments, and, when in direct contact, they can be more susceptible to infecting each other (Castelli & Sulis, 2017; Willen, Knipper, Abadía-Barrero, & Davidovitch, 2017). Migrants often transport diseases from their home country to their new locations (Pavli & Maltezou, 2017), but are also more vulnerable to pathogens in their destination country because their immune systems are unprepared for the new disease environment (Shlomowitz & Brennan, 1994; Watts, 1987).

However, little attention has been paid to the relationship between migration and health. We still do not know much about the impact of different forms of migration on the epidemiology of communicable diseases. Here, we focus on one case of labor migration, temporary workers in the agriculture sector – deemed essential workers – because they are directly connected to international business and communicable diseases. In the United States, 65 percent of the native-born workforce are essential workers, while 69 percent of immigrants and 74 percent of undocumented workers are essential workers (Kerwin & Warren, 2020). Farmers hire many migrant workers, but many others also work for agricultural companies, including multinationals (Oxfam, 2004). As essential workers, temporary agricultural migrants are more susceptible to transmitting communicable diseases, not only during their displacement from and to their countries of origin but also at the workplace, as many have relatively low incomes, live in crowded housing, and are encouraged or even forced to work, even when they are sick (Beatty, Hill, Martin, & Rutledge, 2020).

In addition, temporary agriculture workers are in close contact with nature, making them more prone to be vectors of transmission, and they may lack health insurance, which discourages them from accessing healthcare when they get sick (Connor, Layne, & Thomisee, 2010; Knight, 2020), spreading infections even faster. During the height of the pandemic in the United States, migrant workers were at high risk of contracting COVID-19, as a result of their status as essential workers in maintaining the nation’s food supply, unsafe crowded working and living conditions, and lack of access to social protection and fundamental labor rights. Across the country, COVID cases surged in 2020, affecting fruit and nut harvesters in California (Lopez, 2020), fruit packers in Washington State, tomato growers in South Florida (Crampton, 2020), and agricultural producers in south New Jersey (Shearn, 2020) – all working, living, and dining in crowded surroundings that contribute to contagion. In sum, a global workforce and the displacement of seasonal migrants across borders can contribute to the emergence of pandemics.

Global supply chain management

Many multinationals assemble complex global supply chains – composed of multiple partners located in multiple continents – to reduce production costs and expand into international markets (Gereffi & Lee, 2012; Hernández & Pedersen, 2017). Due to the complexity of global supply chains, companies tend to grapple with effective supply chain monitoring and management (Kim & Davis, 2016). Global supply chains may also transfer health risks across borders through the production and distribution of goods and services (Frenk et al., 2014). For instance, global supply chains require site visits, procurement negotiations, and personnel rotations or interactions – all requiring people to cross borders (Jandhyala & Phene, 2015; Kano, 2018), which could act as a transmission vector. We focus on two connectors between global supply chain management and communicable diseases: (1) supply chain complexity and lack of traceability and (2) supply chain compliance with health, labor, and environmental standards.

Possessing a host of suppliers in multiple countries increases monitoring costs and hinders a multinational’s ability to monitor its supply chain across borders (Webb, 2018). In addition, multinationals’ complex global supply chains often face a situation where sensitive information is not fully exchanged between the buyer and the supplier in the host country (Kim & Davis, 2016; Wilhelm, Blome, Wieck, & Xiao, 2016). For example, this complexity could hinder the traceability of the origin of communicable diseases linked to agricultural multinationals’ activities (Freitas, Vaz-Pires, & Câmara, 2020), likely facilitating their transmission and spread. In the context of supply chains for medicines in developing countries, complex coordination between multiple stakeholders – including donors, manufacturers, government agencies, and prescribers and dispensers – with widely divergent objectives can be a barrier to increasing access to medicines that are essential for addressing communicable-disease epidemics and pandemics (Kraiselburd & Yadav, 2013). Such complex coordination can hinder information flows and monitoring, and slow the delivery of medicines to the end-patient through the supply chain networks (Yadav, 2015).

Poor environmental, working, and health conditions of multinationals’ supply networks could increase the risks of occupational transmission and the stress of working in communities overwhelmed by epidemics (Dharmadhikari, Smith, Nardell, Churchyard, & Keshavjee, 2013; Solinap, Wawrzynski, Chowdhury, Zaman, Abid, & Hoque, 2019). Hence, multinationals may need to monitor suppliers’ compliance with health, labor, and environmental standards to prevent the onset of communicable-disease epidemics. Despite commitments by multinationals to sourcing from suppliers adhering to social, health, and environmental standards, lower-tier suppliers in global supply chains sometimes fail to comply with such standards (Villena & Gioia, 2018, 2020), potentially triggering pandemics. For example, Knudsen (2013) investigates how multinationals’ adoption of international private business regulations affects working conditions in global supply chains. She argues that compliance with such private regulation is a substantial cost burden for smaller business partners. This may incentivize non-compliance, aggravating working conditions across global supply chains. In essence, poor compliance with health, working, and environmental standards along global supply chains could bolster pandemics.

The 2009 H1N1 pandemic likely originated in the Mexican pig farming town of La Gloria, in Veracruz state, on farms owned by Granjas Carroll de México (Schmidt, 2009), which is half-owned by Smithfield Foods – an American pork producer and food-processing multinational (Cohen, 2009). A lack of health control measures in this facility contributed to the emergence of the disease. Factory pig farming relies on concentrated animal feeding operations in which thousands of animals are housed in enclosed areas, which facilitates the mutation of “viral pathogens into novel strains” (Schmidt, 2009: A395). It is purported that concentrated animal feeding operations played a role in the initial outbreak of H1N1, which spread rapidly from the workers to the local community, and across Mexico and other countries via human-to-human transmission. According to estimates of the CDC (2019), H1N1 killed between 151,700 and 575,400 people worldwide during its first year of circulation.

International travel

This section focuses on two travel activities closely linked to international business: business travel and tourism. International business depends on and benefits from international travel, the temporary and voluntary movement of people across different international locations. It is undeniable that international travel, especially by air, allows pathogens to reach any corner of the planet in a few days without being detected, since the incubation period of communicable diseases is usually more than 36 hours (Findlater & Bogoch, 2018). The acceleration of both international business travel and tourism increases the spread of pathogens (Saker et al., 2004; Wilson, 2003), thereby boosting the risk of pandemics (Morse et al., 2012).

First, prior research shows a strong association between the frequency of international travel and the spread of communicable diseases (Fraser, Donnelly, Cauchemez, Hanage, Kerkhove Van, & Hollingsworth, 2009; Hollingsworth, Ferguson, & Anderson, 2007; Hosseini, Sokolow, Vandegrift, Kilpatrick, & Daszak, 2010). The probability that international business travelers will transmit communicable diseases across international borders depends on the disease environment of both the home and host countries (Wilson, 2003). Business travel can increase the spread of communicable-disease viruses, such as those linked to airborne diseases (e.g., influenza, tuberculosis), blood-borne diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS, hepatitis B Virus), vector-borne and zoonotic diseases (e.g., Lyme disease, malaria), and waterborne diseases (e.g., cholera, diarrhea) (World Health Organization, 2012). Even if the tracing may ultimately be inconclusive, some of the first COVID-19 infections are likely to be traced back to international business travelers (CDC, 2020b).

Second, players in the international tourism industry – such as commercial airlines, hospitality, and cruise multinationals – rely on transporting their customers across borders. In what has been called “the democratization of global travel,” the number of international tourist arrivals worldwide broke the record in 2019 with nearly 1.5 billion tourists (World Tourism Organization, 2020). Such temporary mobility of people around the globe can accelerate pandemics because it allows pathogens to quickly reach new international locations. In the past, pandemic flu strains traveled the globe in six to nine months. Tourism can increase the speed at which disease is disseminated, as seen in the case of the H1N1 swine flu; given Mexico’s importance as an international tourist destination, this disease, which originated in Mexico, traveled around the world in just a few weeks (Khan, Arino, Hu, Raposo, Sears, & Calderon, 2009).

Earlier, the 2003 SARS epidemic combined aspects of both business travel and tourism, leading to the first pandemic of the twenty-first century (Cherry & Krogstad, 2004). The disease eventually reached Hong Kong, where an infected Chinese tourist spread the disease to several other guests staying at the same hotel (Reyes et al., 2013). International travel then facilitated SARS spreading to other major urban centers worldwide (Abdullah, Thomas, McGhee, & Morisky, 2006), infecting approximately 8,096 people and killing 774 (World Health Organization, 2015) before quarantines and other public health measures were implemented to control its spread.

MOVING FORWARD

International business activities may not entirely prevent the next communicable disease from emerging. Still, they can be instrumental in keeping a small outbreak from turning into an epidemic, or, worse, spreading globally into a pandemic like COVID-19. In this essay, we identify contextual factors of international business and specific activities of multinationals that could aggravate the impact of communicable diseases on society. These factors have important implications for both international business scholars and managers of multinationals.

Research Implications for International Business Scholars

As international business and management scholars, we intend to bring into our conversations critical perspectives on international business nurtured in other fields, including public health, sustainability, and international development. Even if harsh, some of those critiques are legitimate. Rather than turning our backs on experts in other disciplines, we see the potential for international business scholars to collaborate with health experts to fill knowledge gaps between international business and multinationals on the one side and communicable diseases and global health on the other. Two contributions from public health research can be particularly useful for the international business research community: the commercial determinants of health and the corporate health impact assessment.

Public health scholars refer to the “commercial determinants of health” to describe how “health outcomes are determined by the influence of corporate activities on the social environment in which people live and work: namely the availability, cultural desirability, and prices of unhealthy products. Thus, the environment shapes the so-called lifeworlds, lifestyles, and choices of individual consumers – ultimately determining health outcomes” (Kickbusch et al., 2016, pp. e895–e896). The commercial determinants of health emphasize corporate responsibility in chronic and noncommunicable diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer (de Lacy-Vawdon & Livingstone, 2020; Kickbusch et al., 2016; McKee & Stuckler, 2018; Mialon et al., 2020). This stream of literature can shed light among international business researchers interested in disentangling the connections of international business contextual factors and multinationals’ activities to human health.

Public health experts have also developed tools, such as the corporate health impact assessment which builds on decades of research on the impact of corporations on health. The corporate health impact assessment is, in fact, a systematic valuation of the possible health-related externalities of current companies’ operations, and is readily available to measure the impacts of multinationals’ practices on environmental, social, and economic factors that determine health outcomes (Baum et al., 2016). Thus, this tool may inform multinationals of potential actions to increase their positive health impacts and mitigate negative health impacts to prevent the emergence and spread of communicable diseases in home and host countries, based on their global and national operating contexts and organizational structure and practices. Moreover, even if mainly designed to reduce the business impact on noncommunicable diseases, such a tool can also be extended to include communicable diseases as well as effectively lessen the negative impact of communicable diseases, given that several communicable diseases can develop comorbidities with noncommunicable diseases (Marais, Lönnroth, Lawn, Migliori, Mwaba, & Glaziou, 2013). To bridge public health research with international business, we propose potential research questions on the connections between international business, the emergence of epidemics in host countries, and the shift from epidemics to global pandemics in Table 2.

Practical Implications for Managers of Multinationals

Multinationals are depicted as actors that tend to affect human health negatively. Still, they can also be instrumental in improving the health of all their home-and host-country’s stakeholders (Montiel et al., 2021). Therefore, beyond the potential for multinationals to prevent the emergence and spread of communicable diseases in the near future, companies should take a more prominent role in protecting human health by increasing the health outcomes of not only their employees but also the health of their external stakeholders, including consumers and host-countries’ local communities (Park, Montiel, Husted, & Balarezo, 2022). In the words of Claudia Rivera, Sustainability Director of Colombian food multinational Grupo Nutresa, during a March 2021 interview: “Healthier communities mean healthier business.”

First, multinationals can be better equipped to prevent the emergence of epidemics in host countries if they adopt a reliable corporate health impact assessment tool, similar to the one proposed by public health scholars (Baum et al., 2016). This tool is particularly pertinent to multinationals with subsidiaries in host countries with weak epidemic prevention institutions due to, for example, a lack of resources, limited public health education, or vulnerable healthcare systems. For instance, multinationals could use the health impact assessment to minimize zoonotic events by paying special attention to how their operations at home and abroad affect ecosystems. Moreover, multinationals may share best practices on health risk prevention with their subsidiaries in host countries through technology, knowledge, and innovation transfer, and use that knowledge to curb the spread of different viruses.

Second, in the case of global pandemics, multinationals have the responsibility to exploit their capabilities to reduce the negative repercussions of pandemics because of their global outreach. For example, companies may use their global supply chain capabilities to distribute essential products for communicable-disease control and prevention, including vaccines, masks, and personal protection equipment in countries with difficulty in acting rapidly. Where such capabilities do not exist, multinationals should begin to develop their unique pandemic response capability.

Finally, multinationals do not need to act in isolation in their quest to improve human health. Instead, companies can consider partnerships with host-country governments and civil society organizations. We suggest that global health partnerships become the new normal as part of the multinational’s ordinary activities. For a planet and a human race that seem doomed to dealing with multiple grand challenges simultaneously, including climate change, pandemics, hunger, poverty, and violent conflict, the private sector has to be tapped as a crucial player to implement global sustainability (Margolis & Walsh, 2003; Scherer & Palazzo, 2011), and to be one of the main contributors to the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (Montiel et al., 2021; Van Tulder, Rodrigues, Mirza, & Sexsmith, 2021). Recent evidence shows that, without the active engagement of multinationals during COVID-19, humanity would likely have suffered more during the pandemic. In the words of Núria Molina, Head of EU & Benelux at the Melinda and Bill Gates Foundation, during an interview on September 3, 2021: “The COVID-19 pandemic has shown us the need for global partnerships where multinationals have acted as essential partners of governments and NGOs to secure vaccine production and distribution globally at unprecedented speed.” Not bringing multinationals into global partnerships – enshrined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 17 on Partnerships for the Goals – to address not only the grand challenge of human health but all grand challenges would be an enormous mistake.

NOTES

-

1

This paper adopts the CDC Foundation’s definition of public health as the scholarly field devoted to “protecting and improving the health of people and their communities. This work is achieved by promoting healthy lifestyles, researching disease and injury prevention, and detecting, preventing and responding to infectious diseases. Overall, public health is concerned with protecting the health of entire populations. These populations can be as small as a local neighborhood, or as big as an entire country or region of the world” (CDC Foundation, 2021).

-

2

Public health scholars use the term “comorbidity” to indicate interactions between two or more diseases that can magnify the adverse impacts of both (Marais et al., 2013).

References

Abdullah, A. S. M., Thomas, G. N., McGhee, S. M., & Morisky, D. E. 2006. Impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) on travel and population mobility: Implications for travel medicine practitioners. Journal of Travel Medicine, 11(2): 107–111.

Ahen, F. 2019. Global health and international business: New frontiers of international business research. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 15(2/3): 158–178.

Alirol, E., Getaz, L., Stoll, B., Chappuis, F., & Loutan, L. 2011. Urbanisation and infectious diseases in a globalised world. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 11(2): 131–141.

Allen, L. 2017. Are we facing a noncommunicable disease pandemic? Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 7(1): 5–9.

Alsan, M., Bloom, D. E., & Canning, D. 2006. The effect of population health on foreign direct investment inflows to low- and middle-income countries. World Development, 34(4): 613–630.

Apostolopoulos, Y., & Sönmez, S. F. (Eds.). 2007. Population mobility and infectious disease. Springer.

Arnold, D. G., & Bowie, N. E. 2003. Sweatshops and respect for persons. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(2): 221–242.

Arnold, D. G., & Bowie, N. E. 2007. Respect for workers in global supply chains: Advancing the debate over sweatshops. Business Ethics Quarterly, 17(1): 135–145.

Bagwell, K., & Staiger, R. W. 2004. Multilateral trade negotiations, bilateral opportunism and the rules of GATT/WTO. Journal of International Economics, 63(1): 1–29.

Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. 2007. Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics, 71(1): 72–95.

Baker, R. E., Mahmud, A. S., Miller, I. F., Rajeev, M., Rasambainarivo, F., Rice, B. L., Takahashi, S., Tatem, A. J., Wagner, C. E., Wang, L. F., & Wesolowski, A. 2021. Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 13: 1–13.

Baldwin, R. E., & Evenett, S. J. (Eds.). 2020. COVID-19 and trade policy: Why turning inward won’t work. CEPR Press.

Bapuji, H., & Beamish, P. W. 2019. Impacting practice through IB scholarship: Toy recalls and the product safety crisis. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9): 1636–1643.

Bapuji, H., de Bakker, F. G. A., Brown, J. A., Higgins, C., Rehbein, K., & Spicer, A. 2020. Business and society research in times of the corona crisis. Business & Society, 59(6): 1067–1078.

Bapuji, H., Patel, C., Ertug, G., & Allen, D. G. 2020. Corona crisis and inequality: Why management research needs a societal turn. Journal of Management, 46(7): 1205–1222.

Barnard, H., Deeds, D., Mudambi, R., & Vaaler, P. M. 2019. Migrants, migration policies, and international business research: Current trends and new directions. Journal of International Business Policy, 2(4): 275–288.

Barnett, T., & Whiteside, A. 2002. AIDS in the twenty-first century: Disease and globalization. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Baum, F. E., & Anaf, J. M. 2015. Transnational corporations and health: A research agenda. International Journal of Health Services, 45(2): 353–362.

Baum, F. E., Sanders, D. M., Fisher, M., Anaf, J., Freudenberg, N., Friel, S., et al. 2016. Assessing the health impact of transnational corporations: Its importance and a framework. Globalization and Health, 12(1): 27.

BBC News. 2020. Wuhan: The London-sized city where the virus began. January 23. Retrieved 4 May 2021 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-51202254.

Beatty, T., Hill, A., Martin, P., & Rutledge, Z. 2020. COVID-19 and farm workers: Challenges facing California agriculture. ARE Update, 23(5): 2–4.

Berry, H., Kaul, A., & Lee, N. 2021. Follow the smoke: The pollution haven effect on global sourcing. Strategic Management Journal, 42(13): 2420–2450.

Bird, F. 2016. The practice of mining and inclusive wealth development in developing countries. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(4): 631–643.

Boberg-Fazlic, N., Lampe, M., Pedersen, M. U., & Sharp, P. 2021. Pandemics and protectionism: Evidence from the “Spanish” flu. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8(1): 1–9.

Brundtland, G. H. 2000. Nutrition and infection: Malnutrition and mortality in public health. Nutrition Reviews, 58(s1): S1–S4.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. 1998. Models of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1): 21–44.

Buckley, P. J., Doh, J. P., & Benischke, M. H. 2017. Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9): 1045–1064.

Burns, D. K., Jones, A. P., Goryakin, Y., & Suhrcke, M. 2017. Is foreign direct investment good for health in low and middle income countries? An instrumental variable approach. Social Science & Medicine, 181: 74–82.

Carrington, D. 2020. Pandemics result from destruction of nature, say UN and WHO. The Guardian, June 17. Retrieved 28 Oct 2021 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/17/pandemics-destruction-nature-un-who-legislation-trade-green-recovery.

Castelli, F., & Sulis, G. 2017. Migration and infectious diseases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 23(5): 283–289.

CDC. 2018. Emerging infectious diseases. Retrieved 7 May 2021 from https://web.archive.org/web/20210608022044/https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/emerginfectdiseases/default.html.

CDC. 2019. 2009 H1N1 pandemic – Summary of progress since 2009. Retrieved 28 Oct 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/h1n1-summary.htm.

CDC. 2020a. What is Nipah virus? Retrieved 12 Nov 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/nipah/about/index.html.

CDC. 2020b. First travel-related case of 2019 novel coronavirus detected in United States. Retrieved 30 Jan 2022 from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020b/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html.

CDC. 2021. Zoonotic diseases. Retrieved 3 Nov 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/zoonotic-diseases.html.

CDC Foundation. 2021. What is public health? Retrieved 3 Nov 2021 from http://www.cdcfoundation.org/what-public-health.

Cherry, J. D., & Krogstad, P. 2004. SARS: The first pandemic of the 21st century. Pediatric Research, 56(1): 1–5.

Clapp, J., & Scrinis, G. 2017. Big food, nutritionism, and corporate power. Globalizations, 14(4): 578–595.

Cohen, J. 2009. Texan alleges Mexican pig farm may be liable for pregnant wife’s death from swine flu. Science, May 14. Retrieved 28 Oct 2021 from https://www.science.org/content/article/texan-alleges-mexican-pig-farm-may-be-liable-pregnant-wife-s-death-swine-flu.

Collings, D. G., Scullion, H., & Morley, M. J. 2007. Changing patterns of global staffing in the multinational enterprise: Challenges to the conventional expatriate assignment and emerging alternatives. Journal of World Business, 42(2): 198–213.

Connor, A., Layne, L., & Thomisee, K. 2010. Providing care for migrant farm worker families in their unique sociocultural context and environment. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 21(2): 159–166.

Crampton, L. 2020. In absence of federal action, farm workers’ coronavirus cases spike. POLITICO, June 10. Retrieved 28 Oct 2021 from https://www.politico.com/news/2020/06/09/farm-workers-coronavirus-309897.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. 2018. The evolution of business groups’ corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(4): 997–1016.

Cutler, D. M., & Summers, L. H. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and the $16 trillion virus. JAMA, 324(15): 1495–1496.

Daszak, P., Cunningham, A. A., & Hyatt, A. D. 2000. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife–Threats to biodiversity and human health. Science, 287(5452): 443–449.

de Lacy-Vawdon, C., & Livingstone, C. 2020. Defining the commercial determinants of health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 20(1): 1022.

Dharmadhikari, A., Smith, J., Nardell, E., Churchyard, G., & Keshavjee, S. 2013. Aspiring to zero tuberculosis deaths among Southern Africa’s miners: Is there a way forward? International Journal of Health Services, 43(4): 651–664.

Dobner, J., & Kaser, S. 2018. Body mass index and the risk of infection - from underweight to obesity. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 24(1): 24–28.

Doh, J., Rodrigues, S., Saka-Helmhout, A., & Makhija, M. 2017. International business responses to institutional voids. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3): 293–307.

Dunning, J. H. 1993. Multinational enterprises and the global economy. Addison-Wesley.

Edwards, D. P., Sloan, S., Weng, L., Dirks, P., Sayer, J., & Laurance, W. F. 2014. Mining and the African environment. Conservation Letters, 7(3): 302–311.

Elum, Z. A., Mopipi, K., & Henri-Ukoha, A. 2016. Oil exploitation and its socioeconomic effects on the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 23(13): 12880–12889.

Escandón, K., Rasmussen, A. L., Bogoch, I. I., Murray, E. J., Escandón, K., Popescu, S. V., & Kindrachuk, J. 2021. COVID-19 false dichotomies and a comprehensive review of the evidence regarding public health, COVID-19 symptomatology, SARS-CoV-2 transmission, mask wearing, and reinfection. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21(1): 710.

Estrin, S., Nielsen, B. B., & Nielsen, S. 2017. Emerging market multinational companies and internationalization: The role of home country urbanization. Journal of International Management, 23(3): 326–339.

Evenett, S. J. 2020. Sicken thy neighbour: The initial trade policy response to COVID-19. The World Economy, 43(4): 828–839.

Findlater, A., & Bogoch, I. I. 2018. Human mobility and the global spread of infectious diseases: A focus on air travel. Trends in Parasitology, 34(9): 772–783.

Flanagan, W., & Whiteman, G. 2007. “AIDS is not a business:” A study in global corporate responsibility: Securing access to low-cost HIV medications. Journal of Business Ethics, 73(1): 65–75.

Flecknoe, D., Charles Wakefield, B., & Simmons, A. 2018. Plagues & wars: The ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic as a lesson from history. Medicine, Conflict and Survival, 34(2): 61–68.

FlightConnections. 2020. Direct flights from Wuhan (WUH). Retrieved 10 May 2020 from https://www.flightconnections.com/flights-from-wuhan-wuh.

Fraser, C., Donnelly, C. A., Cauchemez, S., Hanage, W. P., Van Kerkhove, M. D., Hollingsworth, T. D., et al. 2009. Pandemic potential of a strain of influenza A (H1N1): Early findings. Science, 324(5934): 1557–1561.

Freitas, J., Vaz-Pires, P., & Câmara, J. S. 2020. From aquaculture production to consumption: Freshness, safety, traceability and authentication, the four pillars of quality. Aquaculture, 518: 734857.

Frenk, J., Gómez-Dantés, O., & Moon, S. 2014. From sovereignty to solidarity: A renewed concept of global health for an era of complex interdependence. The Lancet, 383(9911): 94–97.

Freudenberg, N. 2014. Lethal but legal: Corporations, consumption, and protecting public health. Oxford University Press.

Gamsa, M. 2006. The epidemic of pneumonic plague in Manchuria 1910–1911. Past & Present, 190(1): 147–183.

Gereffi, G., & Lee, J. 2012. Why the world suddenly cares about global supply chains. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 48(3): 24–32.

Gertner, D., & Rifkin, L. 2018. Coca-Cola and the fight against the global obesity epidemic. Thunderbird International Business Review, 60(2): 161–173.

Getz, K. A. 1997. Research in corporate political action: Integration and assessment. Business & Society, 36(1): 32–72.

Ghauri, P. N., & Rao, P. M. 2009. Intellectual property, pharmaceutical MNEs and the developing world. Journal of World Business, 44(2): 206–215.

Ghosh, S., & Renna, F. 2015. The relationship between communicable diseases and FDI flows: An empirical investigation. The World Economy, 38(10): 1574–1593.

Gifford, B., & Kestler, A. 2008. Toward a theory of local legitimacy by MNEs in developing nations: Newmont mining and health sustainable development in Peru. Journal of International Management, 14(4): 340–352.

Goerzen, A., Asmussen, C. G., & Nielsen, B. B. 2013. Global cities and multinational enterprise location strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(5): 427–450.

Gold, S., Hahn, R., & Seuring, S. 2013. Sustainable supply chain management in “Base of the Pyramid” food projects: A path to triple bottom line approaches for multinationals? International Business Review, 22(5): 784–799.

Gopinath, G. 2020. A long, uneven and uncertain ascent. IMF Blog. Retrieved 1 Feb 2021 from https://blogs.imf.org/2020/10/13/a-long-uneven-and-uncertain-ascent/.

GRAIN. 2007. Corporate power: The palm-oil biodiesel nexus. Retrieved 28 Oct 2021 from https://grain.org/fr/article/entries/611-corporate-power-the-palm-oil-biodiesel-nexus.

Grover, A., Citro, B., Mankad, M., & Lander, F. 2012. Pharmaceutical companies and global lack of access to medicines: Strengthening accountability under the right to health. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 40(2): 234–250.

Gushulak, B. D., & MacPherson, D. W. 2004. Globalization of infectious diseases: The impact of migration. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 38(12): 1742–1748.

Handfield, R. B., Graham, G., & Burns, L. 2020. Corona virus, tariffs, trade wars and supply chain evolutionary design. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40(10): 1649–1660.

Harrison, M. 2012. Contagion. Yale University Press.

Harvey, M. 2021. The political economy of health: Revisiting its Marxian origins to address 21st-century health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health, 111(2): 293–300.

Hernández, V., & Pedersen, T. 2017. Global value chain configuration: A review and research agenda. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 20(2): 137–150.

Himmelberger, J. J., & Brown, H. S. 1995. Global corporate environmentalism: Theoretical expectations and empirical experience. Business Strategy and the Environment, 4(4): 192–199.

Hollingsworth, T. D., Ferguson, N. M., & Anderson, R. M. 2007. Frequent travelers and rate of spread of epidemics. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(9): 1288–1294.

Hosseini, P., Sokolow, S. H., Vandegrift, K. J., Kilpatrick, A. M., & Daszak, P. 2010. Predictive power of air travel and socio-economic data for early pandemic spread. PLOS ONE, 5(9): e12763.

Hu, Y., & Zhou, L. 2019. Wuhan becomes hub for French firms. China Daily, March 27. Retrieved 8 May 2021 from https://www.chinadailyhk.com/articles/252/228/130/1553669511947.html.

Huremović, D. 2019. Brief history of pandemics (pandemics throughout history). In D. Huremović (Ed.), Psychiatry of pandemics: A mental health response to infection outbreak: 7–35. Springer.

Jandhyala, S., & Phene, A. 2015. The role of intergovernmental organizations in cross-border knowledge transfer and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(4): 712–743.

Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. 2022. COVID-19 dashboard. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Retrieved 30 Jan 2022 from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

Jones, K. E., Patel, N. G., Levy, M. A., Storeygard, A., Balk, D., Gittleman, J. L., et al. 2008. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature, 451(7181): 990–993.

Jorgenson, A. K. 2007. Foreign direct investment and pesticide use intensity in less-developed countries: A quantitative investigation. Society & Natural Resources, 20(1): 73–83.

Jorgenson, A. K. 2009. Foreign direct investment and the environment, the mitigating influence of institutional and civil society factors, and relationships between industrial pollution and human health: A panel study of less-developed countries. Organization & Environment, 22(2): 135–157.

Kadandale, S., Marten, R., & Smith, R. 2019. The palm oil industry and noncommunicable diseases. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 97(2): 118–128.

Kahn, L. H. 2011. Deforestation and emerging diseases. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved 20 Nov 2021 from https://thebulletin.org/2011/02/deforestation-and-emerging-diseases/.

Kano, L. 2018. Global value chain governance: A relational perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(6): 684–705.

Kerr, W. A. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and agriculture: Short- and long-run implications for international trade relations. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/revue Canadienne D’agroeconomie, 68(2): 225–229.

Kerwin, D., & Warren, R. 2020. US foreign-born workers in the global pandemic: Essential and marginalized. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 8(3): 282–300.

Khan, K., Arino, J., Hu, W., Raposo, P., Sears, J., Calderon, F., et al. 2009. Spread of a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus via global airline transportation. New England Journal of Medicine, 361(2): 212–214.

Kickbusch, I., Allen, L., & Franz, C. 2016. The commercial determinants of health. The Lancet Global Health, 4(12): e895–e896.

Kim, Y. H., & Davis, G. F. 2016. Challenges for global supply chain sustainability: Evidence from conflict minerals reports. Academy of Management Journal, 59(6): 1896–1916.

King, D. A., Peckham, C., Waage, J. K., Brownlie, J., & Woolhouse, M. E. J. 2006. Infectious diseases: Preparing for the future. Science, 313(5792): 1392–1393.

Kishore, S. P., Kolappa, K., Jarvis, J. D., Park, P. H., Belt, R., Balasubramaniam, T., et al. 2015. Overcoming obstacles to enable access to medicines for noncommunicable diseases in poor countries. Health Affairs, 34(9): 1569–1577.

Knight, V. 2020. Without federal protections, farm workers risk coronavirus infection to harvest crops. NPR, August 8. Retrieved 28 Oct 2021 from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/08/08/900220260/without-federal-protections-farm-workers-risk-coronavirus-infection-to-harvest-c.

Knudsen, J. S. 2013. The growth of private regulation of labor standards in global supply chains: Mission impossible for western small- and medium-sized firms? Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2): 387–398.

Kohl, T., Brakman, S., & Garretsen, H. 2016. Do trade agreements stimulate international trade differently? Evidence from 296 trade agreements. The World Economy, 39(1): 97–131.

Kraiselburd, S., & Yadav, P. 2013. Supply chains and global health: An imperative for bringing operations management scholarship into action. Production and Operations Management, 22(2): 377–381.

Krämer, A., Kretzschmar, M., & Krickeberg, K. (Eds.). 2010. Modern infectious disease epidemiology: Concepts, methods, mathematical models, and public health. Springer.

Labonté, R. 2019. Trade, investment and public health: Compiling the evidence, assembling the arguments. Globalization and Health, 15(1): 1.

Labonté, R., Blouin, C., & Forman, L. 2009. Trade and health. In A. Kay, & O. D. Williams (Eds.), Global health governance: Crisis, institutions and political economy: 182–208. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Labonté, R., Mohindra, K., & Schrecker, T. 2011. The growing impact of globalization for health and public health practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 32(1): 263–283.

Labonté, R., & Ruckert, A. 2019. Migration: Globalization’s historically defining element. In R. Labonté, & A. Ruckert (Eds.), Health equity in a globalizing era: Past challenges, future prospects: 71–92. Oxford University Press.

Laborde Debucquet, D., Mamun, A., & Parent, M. 2020. Documentation for the COVID-19 food trade policy tracker: Tracking government responses affecting global food markets during the COVID-19 crisis. International Food Policy Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.2499/p15738coll2.133711.

Leisinger, K. M. 2005. The corporate social responsibility of the pharmaceutical industry: Idealism without illusion and realism without resignation. Business Ethics Quarterly, 15(4): 577–594.

Leisinger, K. M. 2009. Corporate responsibilities for access to medicines. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(S1): 3–23.