Abstract

Using a large dataset of French municipalities, this article examines the joint determination of the win margin of victory of incumbent mayors and the size of the political budget cycle. A system of two simultaneous equations is estimated with the three-stage least squares method. The main findings are twofold. First, the effects of the win margin on the size of the fiscal cycle are U-shaped. This means that, in a close election, the incumbent mayor tends to reduce public expenditure while, if the incumbent is either certain to win or to lose the election, expenditures tend to be increased. Second, another nonlinear effect is revealed, linking mayors’ time in office to their win margin of victory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Except between 2001 and 2008, the election being postponed to avoid electoral fatigue in 2007, a year in which both the Presidential and Legislative elections were taking place.

Since 2013, the threshold is reduced to 1000 inhabitants.

I consider these municipalities because of the difference in the electoral rules.

According to Foucault and François (2005), the implementation of local political business cycle (LPBC) on the French municipalities raises some difficulties in terms of agenda. While the municipal election is usually planned in March, the budget of year t is voted in December of t − 1 year and is theoretically applicable for year t whatever the result of election. This causes a real ambiguity concerning the importance of LPBC analysis. To limit this ambiguity, they suggest to consider that opportunistic cycles are likely to occur during the year before the election (t − 1) and/or during the year of election.

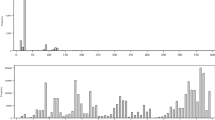

Plots in Fig. 2 are stacked.

Note that these are average expenditures across municipalities.

The election years are 2001, 2008 and 2014. The election of 2001 is not included in the analysis whenever lags, term averages or deviations from term averages are included.

In auto-regressive equations, Nickell (1981) points that the dependent variable’s coefficient is biased due to the correlation between the fixed effects and the lagged-dependent variable.

3SLS is the combination of 2SLS and SUR. It is used in a system of equations which are endogenous, i.e., in each equation endogenous variables on both the left- and right-hand sides of Eq. 2 SLS are computationally cheaper, and, whereas 3SLS is known asymptotically to be more efficient, this need not be so for small samples. 3SLS, then, becomes the estimator of choice only when (1) the researcher considers a gain in efficiency to be important relative to computational cost and (2) when the potential for such a gain is high (Belsley 1988).

See Dalton (2008) for the computation of this index.

References

Aidt, T., F. Veiga, and L. Veiga. 2011. Election results and opportunistic policies: A new test of the rational political business cycle model. Public Choice 148: 21–44.

Akhmedov, A., and E. Zhuravskaya. 2004. Opportunistic political cycles: Test in a young democracy setting. Quarterly Journal of Economics 119: 1301–1338.

Alt, J., and D. Lassen. 2006. Transparency, political polarization, and political budget cycles in OECD countries. American Journal of Political Science 50(3): 530–550.

Alt, J., and S.S. Rose. 2009. Context-conditional political budget cycles. In The Oxford handbook of comparative politics, ed. C. Boix and S.C. Stokes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Balaguer-Colla, M.T., M.I. Brun-Martosa, A. Forteb, and E. Tortosa-Ausina. 2015. Local governments’ re-election and its determinants: New evidence based on a Bayesian approach. European Journal of Political Economy 39(1): 94–108.

Belsley, D.A. 1988. Two- or three-stage least squares? Computer Science in Economics and Management 1(1): 21–30.

Binet, M., and J.-S. Pentecôte. 2004. Tax degression and political budget cycle in French municipalities. Applied Economics Letters 11: 905–908.

Blundell, R., and S. Bond. 1998. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics 87: 115–143.

Brender, A. 2003. The effect of fiscal performance on local government election results in Israel: 1989–1998. Journal of Public Economics 87: 2187–2205.

Cassette, A., and E. Farvaque. 2014. Are elections debt brakes? Evidence from French municipalities. Economic Letters 122(2): 314–316.

Dalton, R.J. 2008. The quantity and the quality of party systems. Comparative Political Studies 41(7): 899–920.

Dassonneville, R., E. Claes, and M.S. Lewis-Beck. 2016. Punishing local incumbents for the local economy: economic voting in the 2012 Belgian municipal elections. Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 46(1): 3–22.

Downs, A. 1957. An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Drazen, A., and M. Eslava. 2010. Electoral manipulation via voter-friendly spending: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics 92(1): 39–52.

Dubois, E. 2016. Political business cycles 40 years after Nordhaus. Public Choice 166(1–2): 235–259.

Efthyvoulou, G. 2012. Political budget cycles in the European Union and the impact of political pressures. Public Choice 153(3): 295–327.

Eslava, M. 2011. The political economy of fiscal deficits: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys 25(4): 645–673.

Farvaque, E., and N. Jean. 2007. Analyse économique des élections municipales: Le cas de la France (1983–2001). Revue d’Économie Régionale et Urbaine 5: 945–961.

Fiva, J.H., and G.J. Natvik. 2013. Do re-election probabilities influence public investment? Public Choice 157(1): 305–331.

Foucault, M., and A. François. 2005. La politique influence-t-elle les décisions publiques locales? Analyse empirique des budgets communaux de 1977 à 2001. Revue Politiques et Management Public 23(3): 1–22.

Foucault, M., T. Madies, and S. Paty. 2008. Public spending interactions and local politics: Empirical evidence from French municipalities. Public Choice 137(1–2): 57–80.

Frey, B., and F.G. Schneider. 1978. An empirical study of politico-economic interaction in the United States. Review of Economics and Statistics 60(2): 174–183.

Gonzalez, M. 2002. Do changes in democracy affect the political budget cycle? Evidence from Mexico. Review of Development Economics 6(2): 204–224.

Greene, W.H. 2000. Econometric Analysis. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Hanusch, M., and D.B. Magleby. 2014. Popularity, polarization, and political budget cycles. Public Choice 159(3): 457–467.

Joanis, M. 2011. The road to power: Partisan loyalty and the centralized provision of local infrastructure. Public Choice 146(1–2): 117–143.

Jones, M.P., O. Meloni, and M. Tommasi. 2012. Voters as fiscal liberals: Incentives and accountability in federal systems. Economics and Politics 24(2): 135–156.

Kneebone, R., and K. McKenzie. 2001. Electoral and partisan cycles in fiscal policy: An examination of Canadian provinces. International Tax and Public Finance 8: 753–774.

Mandon, P., and A. Cazals. 2018. Political budget cycles: Manipulation from leaders or manipulation from researchers? Evidence from a meta-regression analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys 33(1): 274–308.

Martin, P. 1996. Existe-t-il en France un cycle électoral municipal? Revue Française de Science Politique 46(6): 961–995.

Martinez, L. 2009. A theory of political cycles. Journal of Economic Theory 144: 1166–1186.

Nickell, S. 1981. Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica 49: 1417–1426.

Nordhaus, W. 1975. The political business cycle. Review of Economic Studies 42: 169–190.

Peltzman, S. 1992. Voters as fiscal conservatives. Quarterly Journal of Economics CVII(May): 327–361.

Pettersson-Lidblom, P. 2001. An empirical investigation of the strategic use of debt. Journal of Political Economy 109: 570–583.

Philips, A.Q. 2016. Seeing the forest through the trees: A meta-analysis of political budget cycles. Public Choice 168(3): 313–341.

Price, S. 1998. Comment on the politics of the political business cycle. British Journal of Political Science 28(01): 185–222.

Rogoff, K. 1990. Equilibrium political budget cycles. American Economic Review 80: 21–36.

Rogoff, K., and A. Sibert. 1988. Elections and macroeconomic policy cycles. Review of Economic Studies 55: 1–16.

Sakurai, S., and N. Menezes-Filho. 2008. Fiscal policy and reelection in Brazilian municipalities. Public Choice 137: 301–314.

Schultz, K.A. 1995. The politics of the political business cycle. British Journal of Political Science 25(1): 79–99.

Shi, M., and J. Svensson. 2003. Political budget cycles: A review of recent developments. Nordic Journal of Political Economy 29(1): 67–76.

Shi, M., and J. Svensson. 2006. Political budget cycles: Do they differ across countries and why? Journal of Public Economics 90: 1367–1389.

Veiga, L.G., and F.J. Veiga. 2007. Does opportunism pay off? Economics Letters 96: 177–182.

Veiga, L.G., and F.J. Veiga. 2013. Intergovernmental fiscal transfers as pork barrel. Public Choice 155(3): 335–353.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the Editor and two anonymous referees. I am also grateful to Aurelie Cassette, Etienne Farvaque, Jean-Sébastien Pentecôte, Olivier Beaumais, Arnaud Rioual, Jean Baptiste Desquilbet, Stéphane Vigeant, Abdoulaye Papa Diop and Francisco José Veiga for useful comments on previous versions of this article. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Boukari, M. The political budget cycle in French municipal elections: unexpected nonlinear effects. Fr Polit 17, 307–339 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-019-00091-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-019-00091-9