Abstract

There are a number of ways to determine the birth date of a new firm. These include the date of a start-up venture’s initial transactions, initial registry listing, initial labor input, and initial profits. Utilizing the responses from the second Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics (PSED) cohort, it appears that different criteria for a firm’s birth date are associated with substantial differences in the proportion of start-ups that became new firms, the time required to become a new firm, survival following a new firm birth, and the provision of new jobs. This variation may help explain some inconsistent research findings related to firm births.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This measure, reflecting the limits of the Current Population Survey protocol, does not capture those individuals that are working on a business start-up while they are employed or managing another business, which is characteristic of over 80 percent of all nascent entrepreneurs. As shown below, devoting full time to work on a start-up venture occurs relatively late in the process. The Kauffman measure is best considered an indicator, rather than a comprehensive “index.”

See Walls and Associates (2012) for the current effort to reorganize Dun and Bradstreet Data sets.

This assessment represents a major revision of the first approach to this issue developed with access to the one-year follow-up data from the PSED II project (Schoonhoven et al. 2009). Some of the patterns described in the initial analysis have been revised with the additional data from all five annual follow-up interviews.

The author is the founding principal investigator of the PSED research program.

This involved some revision to the screening items and analysis procedures for both the PSED II project and the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor harmonized interviews (Reynolds et al. 2005).

Substantial datasets of employee organizations have been created by the U.S. Census Center for Economic Studies, utilizing listings in the federal social security files where new listings are tracked annually.

Over 80 percent of those active in firm creation do so while they have a full-time job, or are managing another business and, as discussed below, the start-up process takes years to complete. Hence, this “index” does not capture the vast majority of aspects of business creation activity.

There is now substantial descriptive material on these two projects. The background for the PSED I project is discussed in some detail in Reynolds (2000) and Gartner et al. (2004) and the appendices of this latter work volume review the PSED I methodology. The methodology for PSED II is provided in Curtin and Reynolds (2009), an appendix to an initial analysis of some of the major patterns (Curtin and Reynolds 2009). An overview of the PSED I and PSED II cohorts is available in Reynolds (2007) and Reynolds and Curtin (2008, 2011) and Curtin and Reynolds (2009). All the interview schedules, codebooks, and datasets are available at no cost on the project website, ‘www.psed.isr.umich.edu.” The website also provides a 20-page bibliography of the published works and presentations based on PSED-type datasets.

Initial assessments indicated that the same patterns are found with both the PSED I and II datasets.

In the initial screening, the items about profits focused on the prior 12 months, which fail to capture those cases with profits before this period that were re-activating a venture.

This reflects, in part, the elimination of all cases reporting profits immediately before the first interview.

References

Birch, David A. 1979. The Job Generation Process. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Program on Neighborhood and Regional Change for the Economic Development Administration, US. Department of Commerce.

Birch, David A, 1981. Who Creates Jobs? Public Interest, 65: 3–14.

Butani, Shail J., Richard L. Clayton, Vinod Kapan, James R. Spletzer, David M. Talan, and George S. Werking, Jr. 2006. Business Employment Dynamics: Tabulations by Employer Size. Monthly Labor Review, February: 3–22.

Caroll, Glenn R., and Michael T. Hannan. 2000. The Demography of Corporations and Industries. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Curtin, Richard T., and Paul D. Reynolds. 2009. Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics II: Research Design. Appendix A in Reynolds PD, Curtin RT Eds. Business Creation in the United States: Initial Explorations with the PSED II Data Set. Springer, New York.

Fairlie, Robert W. 2014. Kauffman Index of Entrepreneurial Activity: 1996–2013. Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, Kansas City.

Fairlie, Robert W, E. J. Reedy, Arnobio Morelix, and Joshua Russell. 2016. The Kauffman Index of Start-up Activity: National Trends. Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, Kansas City.

Foster, Lucia and Patrice Norman. 2015. The Annual Survey of Entrepreneurs: An Introduction. U.S. Census Bureau, Center for Economic Studies, CES 15–40.

Gartner, William B., Kelly G. Shaver, Nancy M. Carter, and Paul. D. Reynolds (Eds.) 2004. Handbook of Entrepreneurial Dynamics. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Geroski, Paul A. 1995. What Do We Know About Entry? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13: 421–440.

Haltiwanger, John, Lisa M. Lynch, and Christopher Mackie. (Eds.) 2007. Understanding Business Dynamics: An Integrated Data System for America’s Future. National Academies Press, New York.

Haltiwanger, John, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda. 2010. Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large vs. Young. U.S. Census Bureau: Center for Economic Studies, Working paper 10–17.

Hannan, Michael T., and John Freeman. 1989. Organizational Ecology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Klepper, Steven, and John H. Miller. 1995. Entry, Exit, and Shakeouts in New Manufactured Products. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13: 567–591.

Reynolds, Paul D. 2000. National Panel Study of U.S. Business Startups: Background and Methodology. In Jerome A. Katz (Ed.), Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth, Vol. 4. JAI Press, New York.

Reynolds, Paul D, 2007. New Firm Creation in the U.S.: a PSED I Overview. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 3(1): 1–149.

Reynolds, Paul D, 2009. Screening Item Effects in Estimating the Prevalence of Nascent Entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 33(2): 151–163.

Reynolds, Paul D. and Richard T. Curtin. 2008. Business Creation in the United States: Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics II Initial Assessment. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 4(3): 155–307.

Reynolds, Paul D. and Richard T. Curtin. (Eds.) 2009. Business Creation in the United States: Initial Explorations with the PSED II Data Set.. Springer, New York.

Reynolds, Paul D. and Richard T. Curtin. (Eds.) 2011. New Business Creation: An International Overview. Springer, New York.

Reynolds, Paul, Niels Bosma, Erkko Autio, Steve Hunt, Natalie De Bono, Isabel Servais, Paloma Lopez-Garcia, and Nancy Chin. 2005. Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation: 1998-2003. Small Business Economics, 24: 205–231.

Sadeghi, Akbar, James R. Spletzer, and David M. Talan. 2009. Business Employment Dynamics: Annual Tabulations. Monthly Labor Review, May: 45–56.

Schoonhoven, Claudia B., M. Diane Burton, and Paul D. Reynolds. 2009. Reconceiving the Gestation Window: The Consequences of Competing Definitions of Firm Conception and Birth. Chapter 11 in Reynolds, Paul D. and Richard T. Curtin, Eds. Business Creation in the United States: Initial Explorations with the PSED II Data Set. NYC, Springer, pp. 219–238.

Shapero, Albert and Joseph Giglierano. 1982. Exits and Entries: A Study in Yellow Pages Journalism. Frontiers of Entrepreneurial Research: 1982. Babson College, Wellesley.

Walls and Associates. 2012. National Establishment Time-Series (NETS) Database: 2012 Database Description.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

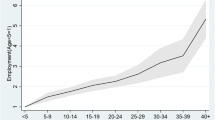

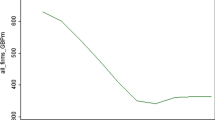

The original version of this article was revised: 30 March 2017. Figures 4, 5 and 6 were incorrectly labelled in the original version of this article but this has since been corrected and an erratum can be found under doi:10.1057/s11369-017-0032-6.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s11369-017-0032-6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reynolds, P.D. When is a Firm Born? Alternative Criteria and Consequences. Bus Econ 52, 41–56 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-017-0022-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-017-0022-8