Abstract

This paper addresses the question of how to account for the distinction between narrator-creating and narrator-neutral narration from a linguistic perspective. I first take issue with the approach by Eckardt (2015), according to which narrator-neutral narration is due to a lack of knowledge about the narrating situation; specifically, I raise an existence problem, an anthropomorphism problem, and a tense problem. Second, combining ideas of the Institutional Theory of Fiction as described by Walton (1990) and Köppe/Stühring (2011) and formal tools of Attitude Description Theory as developed by Maier (2017), I propose an imagination-based alternative account of narrator-neutrality. According to this, the distinction between narrator-creating and narrator-neutral narration is captured by optional existential binding of a narrating situation and a narrator in an imagination component of an interpreter’s mental state. Particular attention is paid to the semantics of the German preterit in fictional narratives. On the one hand, I confirm the famous hypothesis by Hamburger (31977) and her successors in German linguistics that the preterit licenses an atemporal reading and thus an interpretation that eliminates the grammatical need for a narrating situation within the fiction. On the other hand, I reject the prevailing assumption that the preterit in its atemporal reading marks the fiction as such. In lieu thereof, the preterit is argued to instruct interpreters to imagine the story from the perspective of a distant observer.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Artikel behandelt die Frage, wie man den Unterschied zwischen einem Erzählen, das den Eindruck einer erzählenden Instanz vermittelt, und einem Erzählen, das erzählinstanz-neutral ist, aus linguistischer Perspektive erfassen kann. In einem ersten Schritt werde ich gegen den Ansatz von Eckardt (2015) argumentieren, gemäß dem erzählinstanz-neutrales Erzählen auf dem Fehlen von Wissen über die Erzählsituation beruht. So zeige ich, dass der Ansatz zu einem Existenz-Problem, einem Anthropomorphimus-Problem sowie einem Tempus-Problem führt. In einem zweiten Schritt schlage ich eine imaginationsbasierte alternative Erfassung von Erzählinstanz-Neutralität vor; dazu kombiniere ich Ideen der Institutional Theory of Fiction nach Walton (1990) und Köppe/Stühring (2011) mit den formalen Werkzeugen der Attitude Description Theory nach Maier (2017). Der alternative Vorschlag erfasst die Unterscheidung zwischen erzählinstanz-erschaffendem und erzählinstanz-neutralem Erzählen durch optionale Existenzbindung einer Erzählsituation und Erzählinstanz in der Imaginationskomponente des mentalen Zustands von Interpreten. Die Argumentation schenkt der Semantik des deutschen Präteritums in fiktionalen Narrativen besondere Aufmerksamkeit. Einerseits werde ich die berühmte Hypothese von Hamburger (31977) und ihren Nachfolger:innen in der germanistischen Linguistik bestätigen, dass das Präteritum eine atemporale Lesart lizenziert und damit eine Interpretation erlaubt, die die grammatische Notwendigkeit einer Erzählsituation innerhalb der Fiktion aufhebt. Andererseits werde ich die vorherrschende Annahme, das Präteritum markiere in der atemporalen Lesart die Fiktion als solche, zurückweisen. Stattdessen schlage ich vor, dass das Präteritum Interpreten dazu instruiert, die gegebene Geschichte aus der Perspektive einer distanzierten Beobachtung zu imaginieren.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

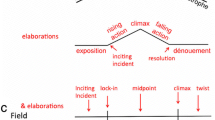

Narrative discourse structures in literary texts can typically be distinguished by whether they suggest the fiction of a narrator or not. Consider, for instance, the contrast between the following opening sequences of two short stories.Footnote 1

-

(1)

Ich muß immer an diesen roten Teufel von einer Katze denken, und ich weiß nicht, ob das richtig war, was ich getan hab. Es hat damit angefangen, daß ich auf dem Steinhaufen neben dem Bombentrichter in unserem Garten saß …

›I always have to think of that red devil of a cat, and I don’t know whether it was right what I did. It all started with me sitting on a pile of stones next to the bomb crater in our garden …‹

(Rinser, Die rote Katze, p. 43)

-

(2)

Plötzlich wachte sie auf. Es war halb drei. Sie überlegte, warum sie aufgewacht war. Ach so! In der Küche hatte jemand gegen einen Stuhl gestoßen. Sie horchte nach der Küche. Es war still …

›Suddenly she woke up. It was half past two. She thought about why she had woken up. Oh! In the kitchen someone had bumped against a chair. She listened toward the kitchen. It was silent …‹

(Borchert, Das Brot, p. 18)

The discourse structure in (1) introduces a first-person narrator and thereby very clearly creates the fiction of a mediating narrating situation with someone telling a story. The discourse structure in (2), by contrast, seems to not provide any clear-cut indication of a narrating situation; it rather suggests immediate access to the given events without interference by a narrating instance. Against this background, this paper addresses the following overarching question: how can the intuitive contrast between narrator-creating and narrator-neutral narration be captured from a linguistic and, more specifically, grammatical perspective?

A detailed discussion of this question is provided by Eckardt (2015). She argues that narrator-neutrality of fictional texts follows from a lack of knowledge about the narrator. Accordingly, examples such as (2) do involve a narrator despite intuitions to the contrary; however, they do not license the fiction of a corresponding specific individual because substantial information about it is missing. The approach goes well with what Köppe/Stühring (2011) call pan-narrator theories, that is, with the common assumption among narratologists that fictional narrators are always present in fictional narratives. It also goes well with the common assumption among linguists that communication is based on the update of information states by speakers’ assertions; in fact, Eckardt’s implementation builds on corresponding context-sensitive formal semantic tools as developed by Stalnaker (1978, 2002), Lewis (1978), and Kaplan (1989). The approach thus also supports a routine account of tense in fictional texts. Specifically, the German preterit in example (2) simply indicates that the speaker (that is, the implicit narrator) makes assertions about a reference time preceding her utterance time (that is, the narrating time), fully on a par with its function in non-fiction. This warrants the conception of narration as a »necessarily retrospective act of sense-making« (Scheffel et al. 2014, p. 873).

It is, however, by no means clear whether this neat picture can be upheld upon closer scrutiny. First, Köppe/Stühring (2011) (among others) have argued against pan-narrator theories from the perspective of literary studies. Based on Walton (1990) and the so-called Institutional Theory of Fiction, they instead propose that fictional narratives are invitations to imaginings that can, but need not involve narrators. This suggests benefiting from these insights for a new linguistic take on narrator-neutrality that, in contrast to Eckardt’s proposal, can dispense with narrator ubiquity. I will sketch such an approach here, based on Maier’s (2017) Attitude Description Theory. Second, this paper will call attention to shortcomings of Eckardt’s proposal from a linguistic perspective and thereby complement the critical evaluation of pan-narrator theories in literary studies. Most notably, the underlying routine account of the German preterit as a purely temporal grammatical marker cannot be taken for granted. As famously argued by Hamburger (31977), the narrated story in narratives such as (2) appears to be present; hence, the preterit in these cases – the so-called epic preterit – does not seem to contribute a temporal anteriority relation to an implicit utterance (that is, narrating) situation. Building on Hamburger’s work, linguists such as Thieroff (1992), Welke (2005), and Bredel/Töpler (2007) propose that the preterit in German conveys an underspecified distance feature that can be specified as ›past‹ (that is, temporally distant) or as ›fictional‹ (that is, distant from the actual world). This amounts to the intriguing hypothesis that the epic preterit marks the fiction as such. I will evaluate this hypothesis by relating it to the more general argument in favor of so-called fake tense in natural language. The most prominent case in point is provided by counterfactual conditionals such as (3) in various languages. As shown by Iatridou (2000) (among others), counterfactual conditionals also involve past morphemes that do not mark temporal anteriority, but distance from the actual world: the speaker of (3) excludes the actual world from the worlds she is talking about.

-

(3)

If Mia hadpst a dog, she wouldfut+pst be happy.

[see Iatridou 2000, (47a)]

While it will be shown that the close link between the preterit and fiction as suggested within German linguistics is ultimately misleading, the idea that the preterit conveys a distance relation that supports atemporal readings will still turn out to be useful. I will propose that the epic preterit marks distance in the spatial domain. Specifically, it instructs the interpreter of a fictional narrative to imagine the situation the narrative is about from the perspective of a physically distant observer who is not participating in this situation. The proposal will thus use the ingredients of the imagination-based account of fictional narration in order to shed new light on the contribution of tense within fiction, departing from both Eckardt’s account and fake-tense-related approaches.

The paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, I will review Eckardt’s (2015) approach to narrator-neutrality of fictional texts. Section 3 will introduce an imagination-based alternative approach to narrator-neutrality and sketch its formal implementation. Section 4 will zoom in on the analysis of the epic preterit within fiction vis-à-vis fake-tense-related approaches. Section 5 offers a conclusion.

2 Eckardt’s (2015) approach to narrator-neutrality and its problems

Eckardt (2015) integrates her approach to narrator-neutrality into the following general framework for the dynamic interpretation of fictional texts; see Stalnaker (1978, 2002), Lewis (1978), and Kaplan (1989) for the relevant background. First, the content of fictional texts is represented by sets of utterance contexts c. The initial set for the reception of a fictional text comprises the expectations of a recipient A about the fictional text at hand before starting to receive it. This set is called story(A)0 and described as in (4); see Eckardt (2015, p. 163). world is a function that maps any utterance context to the world in which the utterance is embedded; correspondingly, speaker and time single out the speaker and the time of utterance.

-

(4)

story(A)0 = {c: The given story could be told in c about world(c) by speaker(c) at time(c) …}

According to Eckardt, these expectations include that world(c) is variably similar to the actual world, but, as fiction, never identical to it.Footnote 2 For the present discussion, the most crucial consequence of the set-up in (4) is that potential utterance contexts c minimally include that there is a telling by a speaker at a time, that is, that there is a narrating situation with a narrator and a narrating time.

Second, the interpretation of a fictional text amounts to the successive update of story(A)0 by the successively given information p1, p2, etc. That is, p1, p2, etc. constrain the respective preceding information state by intersection, as shown by the general pattern in (5). (6) provides a concrete example, assuming that it is the opening sequence of a fictional text. (The temporal information is simplified; see the further discussion for more details.)

-

(5)

story(A)0 ∩ p1 ∩ p2 ∩ … (where pn = sets of utterance contexts)

-

(6)

-

a.

Ich schaue aus dem Fenster. Gestern hat es geregnet.

I look out the window yesterday has it rained

›I am looking out of the window. It was raining yesterday.‹

-

b.

story(A)0 ∩ {c: in world(c), speaker(c) is looking out of the window at time(c)} ∩ {c: in world(c) it is raining the day before time(c)}

-

c.

= {c: the given story could be told in c about world(c) by speaker(c) at time(c); in world(c), speaker(c) is looking out of the window at time(c) and it is raining the day before time(c)}

-

a.

According to this stepwise procedure, each piece of information reduces the set of potential utterance contexts c and thereby enriches our image of the fictional story.Footnote 3 Most importantly, as the narrating situation is part of the fictional story, the procedure also affects the narrating situation in regular ways. The following sources of information about the narrating situation update our image of the narrator and the narrating time.

Assertions about an explicitly given first-person narrator provide the most obvious case in point. For instance, the first sentence in (6a) contributes a fairly specific piece of information about the narrator, namely, that she is looking out of the window while telling her story. A more implicit source of information is given by narrator-oriented interpretations of so-called speaker-oriented expressions such as evaluative adverbs or exclamatives. In (7), for instance, the regret associated with the adverb leider ›regrettably‹ or the surprise associated with the exclamative Wie es regnete! ›How it was raining!‹ can be attributed to the narrator and thereby shape our image of the narrator’s attitude towards the situation at hand.

-

(7)

Es regnete. {Leider regnete es. / Und wie es regnete!}

it rained {regrettably rained it / and how it rained}

›It was raining. {Regrettably, it was raining. / And how it was raining!}‹

However, caution is needed here. It is typical of fictional texts that speaker-oriented expressions are related to a protagonist instead of a potential narrator. In (8), for instance, the surprise is most naturally attributed to Mia, which leads to free indirect discourse; see, for instance, Eckardt (2014) for a comprehensive discussion of free indirect discourse from a linguistic point of view.

-

(8)

Mia schaute aus dem Fenster. Wie es regnete!

Mia looked out the window how it rained

›Mia was looking out of the window. How it was raining!‹

A final source of information about the narrating situation is provided by tense. According to standard assumptions in linguistics (building on Reichenbach 1947; see also Klein 1994), finite clauses combine two layers of temporal information. Tense relates the utterance time and the so-called reference time, where the reference time is defined as the time a speaker talks about. Aspect, by contrast, relates the reference time to the so-called situation time, where the situation time is defined as the run time of the situation described by the verbal predication. For instance, let (9) be a run-of-the-mill non-fictional utterance.

-

(9)

Mia schaute aus dem Fenster.

Mia looked out the window

›Mia was looking out of the window.‹

The tense part of the preterit then conveys that the speaker is talking about a reference time before the utterance time. Assuming that imperfective aspect is used (which is not grammaticalized in German, but is visible in the progressive form of the English translation), the reference time is furthermore said to be a subinterval of the situation time, that is, of the run time of Mia’s looking out of the window.Footnote 4 Under Eckardt’s set-up, this routine account of tense (and aspect) can be used for fictional texts without any change: the speaker is the narrator and the utterance time is the narrating time; correspondingly, if treated as the first sentence of a fictional text, (9) receives the interpretation in (10).

-

(10)

{c: the given story could be told in c about world(c) by speaker(c) at time(c); in world(c), the speaker(c) says about a reference time t before time(c) that t is a subinterval of a situation time t″ at which Mia is looking out of the window}

Crucially, in contrast to speaker-oriented expressions and also in contrast to aspect (see Section 2.3 for protagonist-oriented interpretations of aspect), tense under the routine account is rigidly linked to the narrating time and thus the narrator. Therefore, any finite clause involves a temporal constraint on the narrating situation. While this information is surely thin contentwise – it merely informs about a temporal relation between narrating time and reference time – it still renders the existence of someone narrating a logical necessity.

To summarize the foregoing: There is a principled distinction among information sources about the narrating situation. Sources such as assertions about a first-person narrator and narrator-oriented interpretations of speaker-oriented expressions provide substantial information about the narrator; however, these sources are grammatically optional. Tense, by contrast, provides rather inconspicuous information about the narrator; under the standard temporal interpretation of tense, however, its contribution to the narrating situation is grammatically encoded and thus an infallible indication of its existence.

Against this background, Eckardt defines her notion of narrator-neutrality as follows. Fictional texts are narrator-neutral if they do not provide narrator-related information except for the inevitable information contributed by tense. That is, the impression that a text appears to not have a narrator follows from the fact that the text does not provide substantial information about the narrator. This makes the narrator arbitrary; see the following quote from Eckardt (2015, p. 182):Footnote 5

»In fact, the account does not predict the fiction of a narrator. Many options always mean little knowledge, which can come close to no knowledge at all. If the content of a story could have been told by anybody, the illusion of a protagonist ›somebody‹ simply does not arise.«

This knowledge-based approach seems to reconcile the ubiquitous existence of a narrating situation with the appearance of its nonexistence in an elegant way. In the following, however, I will call attention to three problems with the approach: an existence problem, an anthropomorphism problem, and a tense problem.

2.1 Existence problem

The approach by Eckardt builds on the assumption that poor knowledge about an existing narrator creates the impression that the narrator does not exist. However, it is not made transparent by independent linguistic evidence why this assumption should hold; in fact, independent evidence questions the given assumption. I call this the existence problem.

First, lack of knowledge about an entity usually does not create the impression that the entity does not exist. For instance, the example in (11) supports the impression that there is food and a dog although one does not know much about either.

-

(11)

Ben saß auf der Veranda, schaute in den Nachthimmel und aß zu Abend. Er hörte ein Bellen. Sonst war es still …

›Ben was sitting on the porch, gazing at the night sky and having supper. He heard some barking. Otherwise it was silent …‹

Notably, the relevant entities are introduced as implicit arguments of the predicates essen ›eat‹ and Bellen ›barking‹. That is, the impression that the food and the dog exist cannot be attributed to their explicit introduction by suitable referential expressions. The situation is thus comparable to the introduction of implicit narrators in fictional texts. It is therefore surprising why only the introduction of implicit narrators should block the impression of their existence. This line of thought can be strengthened by the following consideration. Implicit arguments are usually considered discourse-opaque referents that are barred from discourse-related operations such as cross-sentential anaphoric linking; see, for instance, Farkas/de Swart (2003). That is, implicit arguments support the impression of their existence despite their weak discourse status. It is then all the more surprising why implicit narrators should not support a corresponding impression, given that they occupy a very prominent discourse position according to the invariant set-up in (4), namely, the position of the speaker.

Second, the explicit introduction of a narrating situation creates the impression that a narrator exists even if any additional information is lacking, as in (12).

-

(12)

Ich erzähle dir, was passiert ist: Ein älterer Herr …

›I am telling you what happened: An elderly man …‹

The fiction of a narrator in such examples is surely a categorical trait of first-person narration. However, following Eckardt, every fictional context c involves a particular narrating situation with a narrator. The narrator should thus be identifiable, independently of whether she relates to herself by Ich ›I‹ or not. A purely knowledge-based account of narrator-neutrality seems to be at a loss here; the amount of information about narrators does not provide the right tool in order to capture the categorical effect of first-person narration.Footnote 6

2.2 Anthropomorphism problem

The second problem relates to the kind of narrator involved in Eckardt’s proposal. The proposal presupposes an anthropomorphic narrator, that is, someone talking or thinking and living at the narrating time. This presupposition follows from the invariant set-up in (4), repeated in (13), according to which c necessarily includes a regular speech situation.

-

(13)

story(A)0 = {c: The given story could be told in c about world(c) by speaker(c) at time(c) …}

Literary approaches, however, usually provide more cautious descriptions of narrators; see, for instance, the following definition from Martínez/Scheffel (102016, pp. 216 f., my translation).

»Narrator (narrative instance, narrating subject) […] E.g., also collectives, animals or inanimate objects can function as narrators; furthermore, the narrating subject can remain more or less disembodied and speak seemingly independently of any fixed link to space and time.«

Similarly, according to the definition by Margolin (2014), ›narrator‹ primarily denotes an abstract speech position that can only be related to the occupant of this position by interaction of metonymy and anthropomorphization.

To a certain extent, Eckardt’s proposal can be adapted to these definitions easily. Specifically, in order to integrate stories with narrating animals or inanimate objects, one simply has to assume the fiction of a set of contexts c where certain principles of the actual world are suspended. For instance, c could be such that animals, stones, trees, etc. can speak. Nevertheless, as the proposal relies on a narrating situation that is defined as a regular speech situation at a particular time and place within the relevant contexts c, it does not support truely disembodied and abstract narrating instances. In other words, the proposal wrongly predicts that narrators must be conceived of as anthropomorphic concrete entities within the fiction.

Perhaps the most powerful illustration of the problem is provided by fictions about lifeless space or the end of all life; see (14) for a potential example and Byrne (1993) for a related more general argument against pan-narrator theories from a philosophical perspective.

-

(14)

Es gab kein Sprechen, kein Erzählen, kein Leben mehr. Nichts blieb, und das für immer.

›There was no longer any speaking, any narrating, any living. Nothing remained, and this was so forever.‹

Crucially, the set of contexts c as described by the fiction in (14) excludes the existence of a temporally following narrating situation within c. In contrast to the requirements of the invariant set-up in (13), one thus cannot construe a consistent retrospection. I hasten to counter a likely objection to this argument. Of course, it would be consistent for (14) to construe a narrating situation, including a narrator, that is outside of c. However, it is essential for Eckardt’s set-up in (13) that the narrating situation and its narrator are part of c. This is what enables the narrator to talk about her own past in the proposed straightforward way; she cannot talk about her own past in terms of a different c (as this would require additional modal components). I conclude that fictions such as (14) pose a serious problem for essential aspects of Eckardt’s proposal.

2.3 Tense problem Footnote 7

Recall that, following Eckardt (2015), tense necessarily expresses a temporal relation to an utterance time, which is the narrating time in fictional narratives. The existence of a narrating situation with a narrator is therefore a logical necessity within her approach. However, the following discussion will show that this argument rests on a controversial premise. Specifically, prominent literary and linguistic studies argue that tense and, in particular, the preterit need not receive their standard temporal interpretation.

Hamburger (31977) and Weinrich (62001) are the most prominent representatives of this alternative position in literary studies. In a nutshell, they follow the intuition that the content of fictional stories in the preterit appears to be present. Correspondingly, they hold that the preterit in narrative fiction, the so-called epic preterit, does not relate to a past. There is a common objection to this position within narratology, which, however, I do not consider justified. This objection is exemplified by the following quote from Martínez/Scheffel (102016, p. 76) [my translation].

»Hamburger neglects the distinction between the imaginary and the real context of the fictional speech – within the imaginary context it is still true that the act of narration temporally follows the events of the narrated story.«

The objection is based on the assumption that all fictional narratives involve an imagined retrospective narrating situation. However, in light of our overarching question of how to capture speaker-neutrality within fiction, it is precisely this assumption that is up for discussion. Therefore, the given objection is not conclusive.

In German linguistics, Hamburger’s hypothesis has been inspiring for the analysis of the preterit as a grammatical category more generally. Studies such as Thieroff (1992), Welke (2005), and Bredel/Töpler (2007) argue against the view that the preterit is a primarily temporal category. They associate the preterit with an underspecified distance feature that supports both temporal and atemporal specifications. The precise nature of the atemporal specification need not concern us yet; see Section 4 for an evalution of the intriguing hypothesis that the preterit under its atemporal reading marks the fiction as such. For the time being, it is merely crucial that any atemporal analysis of the preterit undermines the idea that the use of tensed clauses in fictional narratives renders the existence of a narrating situation a logical necessity. Against this background, it is worthwhile to consider potential evidence for an atemporal analysis of the preterit in German.

2.3.1 Grammatical reasons for the feasibility of an atemporal preterit

From a grammatical perspective, it is a widely received view that the temporal contribution of the preterit in German differs in principled ways from the contribution of the present perfect in German.Footnote 8 Roughly, the preterit combines past tense with perfective, imperfective, or prospective aspect, whereas the present perfect combines present tense with perfect aspect. As a consequence, a speaker using the preterit talks about a reference time TR before her utterance time TU and locates the situation time TS either in TR, around TR, or after TR. A speaker using the present perfect talks about a reference time TR that coincides with her utterance time TU and locates the situation time TS before TR. A schematic overview is given in (15) and (16). The examples in (17) provide a minimal pair for illustration (assuming imperfective aspect for the preterit); notably, in both examples, Mia’s sleeping takes place before TU, which accounts for their intuitive similarity.

-

(15)

preterit:

-

a.

TR < TU (past)

-

b.

TS ⊂ TR (perfective) or TS ⊃ TR (imperfective) or TS > TR (prospective)

-

a.

-

(16)

present perfect:

-

a.

TR = TU (present)

-

b.

TS < TR (perfect)

-

a.

-

(17)

-

a.

Mia schlief.

Mia sleep:pret

›Mia was sleeping.‹

\(\leadsto\)Footnote 9 The speaker talks about her past as a time when Mia is sleeping.

-

b.

Mia hat geschlafen.

Mia have:prs sleep:ptcp

›Mia has slept.‹

\(\leadsto\) The speaker talks about her now as a time after Mia’s sleeping.

-

a.

This set-up has the following consequences for narratives; see, in particular, Welke (2005, Chapter 7.3) for a corresponding line of thought. As utterances in the present perfect are about the now of the speaker, the reported past events are always considered from the perspective of this now. That is, every use of the present perfect invokes the dependence of the events on the utterance time. Therefore, the perfect is not a good means to establish narratives that are independent of the utterance time; correspondingly, it does not support narratives that consist of self-contained chains of events. The preterit is different. As utterances in the preterit are about a time that differs from the utterance time, the reported events are only indirectly linked to the now of the speaker. Therefore, the preterit is typical for independent narratives, that is, for chains of events where, instead of the utterance time, the events themselves provide the reference time for respective subsequent events. This independence from the time of utterance sets the stage for an invisible utterance time and thus an atemporal interpretation of the preterit; Welke (2005, p. 301) [my translation] concludes for fictional narratives in particular: »it [= TU] is nearly abandoned in fictional texts.«Footnote 10

As far as I know, the previous research has not linked the given grammatical distinction between the preterit and the perfect to the controversy about narrator-neutrality in fictional texts. However, there is an obvious link. As the perfect involves a visible time of utterance and thus, more generally, a visible utterance situation, it continuously indicates that there is someone talking; therefore, it should usually not support narrator-neutral fictional discourse. The preterit, by contrast, can abandon the time of utterance and thus the utterance situation; therefore, it should support narrator-neutral fictional discourse. In fact, this prediction is borne out. Consider the examples in (18), based on the supposition that they each form the beginning of some fictional text.

-

(18)

-

a.

Ben hat am Schreibtisch gesessen, einen Kaffee getrunken und

Ben have:prs at the desk sit:ptcp a coffee drink:ptcp and

aus dem Fenster geschaut. Es hat geregnet. Da bin ich

out of the window look:ptcp it have:prs rain:ptcp there be:prs I

mir sicher!

refl sure

›Ben has been sitting at the desk, drinking a coffee and looking out of the window. It has been raining. I am sure about it!‹

-

b.

Ben saß am Schreibtisch, trank einen Kaffee und

Ben sit:pret at the desk drink:pret a coffee and

schaute aus dem Fenster. Es regnete. #Da bin ich mir sicher!

look:pret out of the window it rain:pret there be:prs I refl sure

›Ben was sitting at the desk, drinking a coffee and looking out of the window. It was raining. I am sure about it!‹

-

a.

In both examples, the text first provides some information about Ben and the weather and then introduces a first-person narrator, which makes explicit that the given information originates with this narrator. Crucially, the choice of temporal forms in the first two sentences yields a subtle contrast. In (18a), where the present perfect is used, the sudden introduction of an explicit narrator comes as little surprise. This is expected under the assumption that the existence of a narrating situation is already marked by the perfect itself. By contrast, in (18b) where the preterit is used, the sudden introduction of a narrator is surprising and thus renders the discourse structure slightly incoherent. This effect can be accounted for by the assumption that the preterit supports an atemporal use that is independent of a narrating situation.Footnote 11

The given reasoning is also compatible with the examples from the introduction, repeated in (19) and (20). Subscripts on finite verbs specify which temporal form is used in the respective sentence.

-

(19)

Ich mußprs immer an diesen roten Teufel von einer Katze denken, und ich weißprs nicht, ob das richtig warpret, was ich getan habprs prf. Es hatprs prf damit angefangen, daß ich auf dem Steinhaufen neben dem Bombentrichter in unserem Garten saßpret …

›I always have to think of that red devil of a cat, and I don’t know whether it was right what I did. It all started with me sitting on a pile of stones next to the bomb crater in our garden …‹

(Rinser, Die rote Katze, p. 43)

-

(20)

Plötzlich wachtepret sie auf. Es warpret halb drei. Sie überlegtepret, warum sie aufgewacht warpst prf. Ach so! In der Küche hattepst prf jemand gegen einen Stuhl gestoßen. Sie horchtepret nach der Küche. Es warpret still …

›Suddenly she woke up. It was half past two. She thought about why she had woken up. Oh! In the kitchen someone had bumped against a chair. She listened toward the kitchen. It was silent …‹

(Borchert, Das Brot, p. 18)

The example in (19) introduces a first-person narrator and thereby creates the fiction of a mediating narrating situation. As expected, this narrator-creating example licenses the use of the present perfect. Furthermore, the example clearly advances the impression that the narrator is reporting on events of her past. That is, there is a narrating situation in which previous events are treated as factual, which conforms to the standard conception of fictional narration as a truly retrospective act by an imagined narrator. There are also two preterit forms in (19); however, as they receive a standard temporal interpretation in the given context, they do not challenge the suggested line of interpretation.

The grammatical set-up of the narrator-neutral example in (20) is very different. Most importantly, the predominant temporal form here is the preterit, while the present perfect is not used at all. In this case, the impression of a retrospective narrating act is completely missing. This effect can easily be explained by the current approach, according to which the preterit licenses atemporal interpretations. It is however at odds with approaches such as Eckardt’s, according to which the preterit should always receive its standard temporal interpretation and thus unequivocally evoke a readily available narrating situation. Notably, the use of the past perfect in (20) is fully regular as well. According to standard assumptions, the past perfect combines the interpretation of the preterit with the interpretation of perfect aspect; see Reichenbach (1947), Klein (1994), and Eckardt (2014). The current approach thus predicts for (20) that it combines an atemporal interpretation of the preterit with anteriority of event times as conveyed by aspect; this is intuitively correct: the past perfect in (20) merely indicates that the relevant events – the waking up and the bumping against the chair – happen before the events in the main chain of situations, which is not further specified timewise. One should finally note that the relevant retrospection in this case is not attributed to a narrator (which would undermine narrator-neutrality), but to a protagonist, that is, to the person sie ›she‹ refers to. This leads to (free) indirect discourse and the impression that the protagonist is reflecting on events in her immediate past (compare also the use of the attitude verb überlegen ›think‹ and the interjection Ach so! ›Oh!‹). Generally, this option is due to the fact that, in contrast to tense, aspect is a shiftable indexical category; see Eckardt (2014) for an elaborate discussion of the past perfect as a trigger for free indirect discourse and the next section for further information on the sensitivity of aspect to the perspective of a protagonist.Footnote 12

In sum, the preterit in fact supports the interpretation of fictions where an imagined retrospective narrating situation is missing. This substantiates the assumption that the preterit can have an atemporal reading.Footnote 13

2.3.2 Temporal adverbials and atemporal preterit

The most prominent argument in favor of atemporal tenses originates with Hamburger (31977) and her consideration of tense forms in combination with temporal adverbials; see (21a) and the analogous simplified variant in (21b).

-

(21)

-

a.

Aber am Vormittag hatte sie den Baum zu putzen. Morgen warpret Weihnachten.

›But in the morning she had to clean the tree. It was Christmas tomorrow.‹

[see Hamburger (31977, p. 65), citing from Die Bräutigame der Babette Bomberling ›The bridegrooms of Babette Bomberling‹ by Alice Berend]

-

b.

Mia lächelte. Morgen war Weihnachten.

Mia smile:pret tomorrow be:pret Christmas

›Mia was smiling. It was Christmas tomorrow.‹

-

a.

The argument is straightforward: The adverbial morgen ›tomorrow‹ locates Christmas in the future. If the preterit received its standard temporal interpretation, it should locate Christmas in the past and thus yield a contradiction. As no contradiction arises, the conclusion is that the preterit must receive a non-standard atemporal interpretation here. However, once a more nuanced view on the semantics of temporal information and perspective-taking is adopted, the given argument loses its validity; see, for instance, Rauh (1985) and Eckardt (2014, Chapter 4) for detailed discussions. In order to show why the examples are considered compatible with a purely temporal interpretation of the preterit, I will sketch an analysis of (21b) along the lines of Eckardt’s proposal.

The proposal is based on the familiar distinction between tense and aspect on the one hand and well-known shifts between narrator perspective and protagonist perspective on the other. First, the preterit in (22) conveys its standard past meaning; see (22a). Accordingly, the narrator is talking about a reference time TR before her utterance time TU. Second, the preterit is assumed to be underspecified with regard to aspect (recall (15) from above). In this particular case, it can thus license prospective aspect, according to which the relevant situation time TS is located after TR (and before TU); see (22b). Finally, the proposal makes use of established facts about perspective-taking. Adverbials such as morgen are shiftable indexicals, which supports their interpretation relative to the thinking of a protagonist TUprot and the creation of free indirect discourse. Furthermore, following Doron (1991), free indirect discourse is characterized by the generalization that reference time TR and the protagonist’s thinking TUprot coincide; see (22c).

-

(22)

Morgen war Weihnachten.

tomorrow be:pret Christmas

-

a.

past tense \(\leadsto\) TR < TU: the narrator is talking about a past time TR.

-

b.

prospective aspect \(\leadsto\) TS > TR (and < TU): Christmas is after TR (and before TU).

-

c.

adverb morgen \(\leadsto\) TS is one day after TUprot; TUprot = TR: Christmas is one day after TUprot/TR (and before TU).

-

a.

The overall result for (21b) is intuitively correct (see, however, below for qualifications regarding the narrator). A narrator says about a time before her utterance time that Mia is smiling while thinking that it will be Christmas the next day. In a nutshell, the temporal contradiction invoked by Hamburger’s original argument does not arise because only tense is rigidly bound to the perspective of the narrator; aspect and adverbs, by contrast, can be bound to the perspective of a protagonist.

The result, then, is that Hamburger’s prominent examples do not provide conclusive evidence in favor of an atemporal preterit. Crucially, however, the relevant examples do not provide conclusive evidence against it either. Eckardt’s approach merely shows in which way future-oriented adverbials can be reconciled with a standard temporal interpretation of the preterit; it does not show that this type of approach is mandatory. Specifically, only the reference time TR, corresponding to the time of Mia’s thinking TUprot, and the situation time TS of Christmas are necessary for a temporally adequate representation of the scenario under discussion. There is simply no intuition according to which recipients must imaginatively represent a retrospective narrating situation. Correspondingly, the core meaning of example (22) would also be captured without condition (22a) and, thus, without the standard temporal interpretation of the preterit.

The obvious follow-up question is whether there are adverbial examples that could distinguish between both approaches at all. Examples with adverbials that are interpreted relative to a protagonist will be of no avail. The protagonist perspective is bound to aspect, which is underspecified in the case of the preterit and as such uninformative for the controversial part of the preterit’s contribution. It is more promising to consider the interaction between the preterit and temporal adverbials that must be interpreted relative to a narrator; see (23), where the relevant sentence is marked by italics.

-

(23)

Ben wachte früh morgens auf und machte sich an die Arbeit am Boot. Er hatte, seit er auf der Insel gestrandet war, jedes Zeitgefühl verloren. Morgen hattepret er Geburtstag, ohne dass er davon wusstepret.

›Ben woke up early in the morning and set to work on the boat. Since he had become stranded, he had lost all sense of time. It was his birthday tomorrow without his knowing it.‹

In the given context, the future-oriented adverbial morgen is interpreted relative to a narrator; nevertheless the preterit is used. This reading is at odds with the standard temporal approach to the preterit; see (24) with contradictory requirements: Ben’s birthday should be both before and after the narrating time TU.

-

(24)

Morgen hatte er Geburtstag.

tomorrow have:pret he birthday

-

a.

past tense \(\leadsto\) TR < TU: the narrator is talking about a past time TR.

-

b.

prospective aspect \(\leadsto\) TS > TR (and < TU): Ben’s birthday is after TR (and before TU).

-

c.

adverb morgen \(\leadsto\) TS is one day after TU: Ben’s birthday is one day after TU.

-

a.

By contrast, the contradiction does not arise under an atemporal interpretation of the preterit. There could be a co-temporal narrator such that her reference time TR coincides with her utterance time TU; correspondingly, Ben’s birthday is simply located on the subsequent day. The example in (23), then, provides evidence in favor of the assumption that the preterit can receive atemporal readings. While I consider this line of thought sound, it comes with a flaw. I speculate that it is more common for narratives to either not have a narrator (which goes well with an atemporal preterit) or to have a truly retrospective narrator (which goes well with a temporal preterit). Therefore, the peculiar configuration that involves a co-temporal narrator and can thereby bring out a substantial difference of the standard approach to the preterit from Hamburger’s position is probably untypical. This calls into question whether the given argument is in fact fully reliable.

2.4 Interim conclusions

Eckardt (2015) argues that fictional narratives invariably involve a narrating situation with a narrator, and that any impression to the contrary is due to a lack of knowledge about these components. I have called attention to three problems with this approach. First, it remains unclear why the existence of an arbitrary narrator should create the impression of its nonexistence. Second, the narrating instance is potentially more abstract than predicted by the assumption that there is always an anthropomorphic narrator within the story being told. Third, it cannot be taken for granted that the preterit must relate utterance time and reference time and thereby make the existence of a narrating situation a logical necessity. In particular, evidence drawn from contrasts between the preterit and the present perfect and from the combinatorics of the preterit with temporal adverbials complies with the opposing view that the preterit also licenses an atemporal use. In the following sections, I will tackle an alternative approach to narrator-neutrality in fictional narratives and specify in more detail the use potential of the preterit.

3 Outline of an imagination-based approach to speaker-neutrality

Fictional narratives can be understood as invitations to imagine; see, in particular, Walton (1990) and the Institutional Theory of Fiction as summarized by Köppe/Stühring (2011, Section 2). Against this background, Köppe/Stühring (2011, p. 74, p. 62) argue against the ubiquity of a narrator:

»The question whether a text has a fictional narrator comes down to whether the text authorizes imaginings about a fictional narrator.«

They thus distinguish between the two options in (25).

-

(25)

-

a.

›Imagine that a narrator narrates that …‹

-

b.

›Imagine that …‹

-

a.

I will essentially follow their position here. In order to spell out its linguistic implementation, I will take advantage of formal tools as independently argued for by Maier (2017).

The main concern of Maier (2017) is a new solution to a long-standing puzzle about the semantics of fictional names, namely, the paradox that their referents can simultaneously be said to bear properties of individuals of flesh and blood and to not exist; see the fictional and the metafictional statement in (26) for exemplification.

-

(26)

-

a.

Frodo is a hobbit born in the Shire.

-

b.

Frodo is a fictional character invented by Tolkien.

[see Maier 2017, (1)]

-

a.

For our purposes, a very rough sketch of Maier’s solution suffices.Footnote 14 His solution builds on a formalization of an imagination-based approach to fiction in terms of Discourse Representation Theory (= DRT; see Kamp/Reyle 2011 for a general overview of Discourse Representation Theory). In DRT, the mental states of interpreters form an integral part of the semantic representations for linguistic units. Correspondingly, the interpretation of a discourse is modeled by dynamic updates of mental representations. The integration of mental states is particularly evident in what Maier calls psychologistic versions of DRT, where mental states receive explicit structural representations; see Kamp (1990, 2015) for the relevant extension of standard DRT. Specifically, Maier (2017) takes advantage of the idea that the mental state of an interpreter unifies distinct but interacting attitudes. Formally, each attitude description consists of a pair ⟨attitude; box⟩, where attitude labels the attitude under discussion and box represents its content in the form of the standard box notation for discourse representation structures. For (26), Maier proposes the set of attitude descriptions in (27).

[see Maier 2017, (29)]

The boxes can be read as usual: the upper part introduces existential quantification over variables, while the lower part introduces conditions on these variables; for instance, the first box thus says that there is a x such that x is an author with the name Tolkien. The structure of the mental state of the interpreter is given by the attitudes that embed the pieces of information as captured in the boxes. The first attitude description, labeled anch, is a so-called internal anchor that describes in which mind-internal way an interpreter is acquainted with a discourse referent that is anchored to the external world and thus external to the mental state of the interpreter. The given anchor for Tolkien captures that he is known to interpreters by virtue of being an author.Footnote 15 For the present discussion, the distinction between the second and the third attitude descriptions is the most important one. The attitude labeled imag comprises what interpreters imagine. Specifically, if interpreters accept a text they receive as fiction, they follow the invitation to imagine as suggested by Walton (1990) and successively update their imag-component. This is the case for the fictional statement in (26a); its representation in (27) says that the interpreter is authorized to imagine that there is a y and a z (compare the upper box in the discourse representation structure) and that y is called Frodo, is a hobbit, and is born in z called the Shire. The attitude labeled bel comprises what interpreters believe to be true. Specifically, if interpreters receive ordinary assertions about the actual world and trust the respective speaker, they update their bel-component. This is the case for the metafictional statement in (26b); its representation in (27) says that interpreters are authorized to believe that y is fictional and invented by x. Crucially, there is no existential quantification over y (that is, Frodo) in the bel-component (compare the lack of an upper box) capturing that interpreters do not subscribe to the contradictory belief that a non-existent entity exists. In a nutshell, metafiction is thus characterized by the fact that a referent described in the bel-component is bound within the imag-component such that someone’s belief becomes dependent on imagination.

Maier (2017) is not concerned with speaker-neutrality within fictional narratives. However, his framework offers a straightforward approach to it. It simply suggests that optional existential binding within the imag-component represents whether a narrative licenses the fiction of a narrating situation with a narrator or not. Specifically, I suggest the schematic representation in (28), where ⌜⌝ marks optionality.

According to the anch-component, there is an r that an interpreter considers as anchored to the actual external world by virtue of being a fictional narrative about some context c. In contrast to the construal of narrative contents as sets of contexts (recall the set-up in Eckardt 2015), I thus assume that fictional narratives describe particular contexts c. This is in line with the common intuition that recipients of a fictional narrative have a particular context in mind during reception.Footnote 16 Correspondingly, c is not anchored to the external world, but existentially bound within the imag-component, which, in turn, comprises all information that the fictional narrative provides about c. According to the set-up in (28), c can, but need not include a situation e of a narrator x narrating c. A fictional narrative r about c can then be defined as speaker-neutral iff c does not include a narrating situation e with a narrator x narrating c. In other words, the imag-component of a speaker-neutral fictional narrative r existentially binds a context c, while it lacks the variables and conditions marked by ⌜⌝ in (28).

From a grammatical perspective, the most urgent follow-up question is in which way the given approach can cover the obligatory contribution by tense, in particular, the contribution by the epic preterit. An answer will be pursued in the next section. However, before turning to the epic preterit, I will briefly comment on a principled objection to the given approach raised by a reviewer. The reviewer argues that the reduction of fictional narratives to an invitation to imagine is a clear oversimplification. The approach would hardly do justice to the variety of narrative genres, narrative functions, and narrative instances. Specifically, the reviewer calls attention to narratives about real events that could be conceived of as invitations to imagine as well. While I agree with the reviewer that the given picture is simplified, I do not think that this simplification disqualifies the given approach from being useful. The main aim of this section is to highlight the principled merits of an approach to fictional names and speaker-neutrality in terms of interacting attitude descriptions (in lieu of alternative formal frameworks). In order to abstract away from potential complexities, the given illustration intentionally builds on ordinary fictional narratives; for such simple cases, it is sufficient to distinguish between attitudes such as imag, bel, and anch and to use coarse-grained predicates such as ›fictional‹ or ›fictional narrative‹. That said, it is surely legitimate to ask whether the given approach could handle other cases as well. I think that the model in fact has the relevant potential. The main reason for this belief is that the model is designed to capture potentially fine-grained mental states. Let us, for instance, take a narrative for which an interpreter assumes that it is narrated by a real narrator and that it comprises real events. In this case, neither the narrating situation including the narrator nor the given events should be bound within the imag-component. In lieu thereof, the relevant entities would be anchored to the external world of the interpreter or be bound to her belief; that is, the upper box of the discourse representation structure in the imag-component would remain empty. One could also make more subtle distinctions by assigning some entities to the imag-component and others to anch or bel. In fact, Maier (2017, pp. 23–24) already discusses the case of non-fictional names in fictional narratives. His example is the interpretation of Napoleon in Tolstoj’s War and Peace; he proposes that the events in which Napoleon participates are bound within the imag-component, while Napoleon himself is interpreted via anch. I am agnostic as to the question of whether this approach to narratives that are (partially) about real events and real participants suffices. Another option would be to distinguish between different kinds of imagination such that the attitudes themselves come with different implications. In any case, a logical model that is sensitive to the mental states of interpreters seems to have the necessary expressive power.

4 The semantics of the epic preterit

Building on Hamburger (31977), Thieroff (1992), Welke (2005), and Bredel/Töpler (2007), I have argued in Section 2.3 that the preterit in German licenses an atemporal use where no anteriority relation is contributed to an implicit narrating situation. Recall that this is a logical prerequisite for an account of speaker-neutrality in terms of an optional narrating situation in the imagination component of an interpreter’s mental state. But what, then, is the semantics of this atemporal epic preterit? As already noted in Section 2.3, the most prominent claim is that the preterit in German conveys an underspecified distance feature that can be specified as either temporally distant or as distant from the actual world. The first specification yields the temporal past meaning; the second specification is the crucial atemporal meaning, according to which the epic preterit marks an utterance as fiction. If applied to the imagination-based approach to fiction as outlined in Section 3, the epic preterit thus denotes the invitation to an update of the imagination component. As far as I see, however, the consequences of this intriguing claim have not been discussed in substantial depth in the previous literature. In Section 4.1, I will comply with this desideratum by evaluating it against the background of more general discussions about atemporal tense, so-called fake tense, within formal semantics.Footnote 17 The upshot will be that the epic preterit cannot be treated as a marker for fiction. In Section 4.2, I will outline an alternative analysis according to which the preterit marks imagination from a distance and thus instructs interpreters on how they should imagine the contents of the fictional narrative they receive.

4.1 The epic preterit as fake tense?

The discussion about fake tense has primarily evolved from the observation that, crosslinguistically, counterfactual conditionals (= CFs) make use of past-morphemes; see the examples in (29) from English.

-

(29)

-

a.

If Mia hadpst a dog, she wouldfut+pst be happy.

-

b.

If Ben tookpst this syrup, he wouldfut+pst get better.

[see Iatridou 2000, (47a)/(8)]

-

a.

The standard analysis in formal semantics originates with Iatridou (2000) (see Schulz 2014 for refinements and Romero 2014 for an alternative formal perspective). Its key ingredients are the following. First, the past-morpheme is assumed to agree with an exclusion feature ExclF as given in (30). Depending on whether the exclusion operates on the temporal or modal domain, ExclF gives rise to either the temporal and thus standard past reading in (31a) or to the modal and thus fake tense reading in (31b).Footnote 18

-

(30)

The x that the speaker is talking about excludes the x that for all we know is the x of the speaker; x can be times or worlds.

[see Iatridou 2000, (49)]

-

(31)

-

a.

Temporal reading: The topic time excludes the time of the speaker (= TU).

\(\leadsto\) standard past

-

b.

Modal reading: The topic worlds exclude the worlds of the speaker (= the actual world w@). \(\leadsto\) fake past

[see Iatridou 2000, (52)/(57)]

-

a.

Second, the interpretation of CFs builds on the modal reading in (31b) in the following way. A crucial trait of CFs of the form if p, q is that they pragmatically implicate (in other words, suggest) that p is false without, however, semantically entailing it. For instance, as shown by (32), the counterfactual implicature of CFs can be made explicit without being redundant (which is a standard test for implicatures in pragmatic analyses following Grice 1975).

-

(32)

Wenn Mia einen Hund hätte, wäre sie glücklich. Aber sie

if Mia a dog have:pst:sbjv be:pst:sbjv she happy but she

hat keinen Hund.

have:prs no dog

›If Mia had a dog, she would be happy. But she does not have a dog.‹

This is in line with the modal reading as sketched in (31b). On the one hand, the given semantics merely says that a CF of the form if p, q is about worlds that exclude the actual world; therefore, semantically speaking, the CF is not about the actual world w@ and thus does not make explicit whether p holds in w@ or not. On the other hand, the counterfactual intuition for CFs can easily be derived from (31b) by the standard pragmatic reasoning in (33); see Iatridou (2000, pp. 247-249).

-

(33)

Let a speaker S utter a CF if p, q. Then, if S believed that p is true in w@, S would not exclude w@ from the worlds she is talking about. As she does precisely this by using ExclF, she implicates that p is false in w@.

Against this background, one might suggest that the epic preterit agrees with the exclusion feature ExclF as well and thereby identifies the fiction as such. In fact, Schulz (2014, p. 133) hints at this direction without, however, discussing a concrete proposal and its consequences. A rough sketch along the lines of Iatridou’s analysis for CFs could look as in (34).

-

(34)

-

a.

The worlds that a given narrative is talking about exclude the worlds that for all we know are the worlds of the narrative (= w@).

-

b.

Implicature: The propositions p of the narrative (that is, its content) are false in w@ and thus fiction.

-

a.

The given suggestion thus seems to pave the way for a precise and systematic take on the contribution of the atemporal preterit in fictional narratives. However, for reasons to be discussed next, I consider the presumptive close link between the epic preterit and the marking of fiction flawed in fundamental ways.

First, there is a morphological problem. The contrast in (35) shows that CFs in German require additional subjunctive marking, while the epic preterit prohibits this.Footnote 19

-

(35)

-

a.

Wenn Mia den Sirup nähme, würde es ihr besser

if Mia the syrup take:pst:sbjv aux:pst:sbjv it her better

gehen.

go

›If Mia took the syrup, she would get better.‹

-

b.

#Mia säße am Fenster und würde seufzen. Es

Mia sit:pst:sbjv at the window and aux:pst:sbjv sigh it

würde regnen.

aux:pst:sbjv rain

›Mia would be sitting at the window sighing. It would be raining.‹

-

a.

In order to predict that only CFs require the subjunctive, one might argue that the exclusion feature ExclF agrees with the subjunctive only as a local sentential feature, but not as a global discourse feature. However, this assumption would at the same time undermine the crucial idea that ExclF can agree with the epic preterit. If one conceived of ExclF as a global discourse feature for the identification of fiction, it could not interact with this local morphological category either.

The use of present tense reveals a second problem. Iatridou (2000, pp. 252-253) argues that the present supports a modal reading as well. This fake present differs from the fake past by marking the lack of exclusion. By using a corresponding example such as (36), a speaker thus conveys that she does not exclude the actual world w@ from the worlds she is talking about.

-

(36)

Wenn Mia den Sirup nimmt, wird es ihr besser gehen.

if Mia the syrup take:prs aux:prs it her better go

›If Mia takes the syrup, she will get better.‹

The problem now is this: If the epic preterit were an instance of fake past, the epic present should also be an instance of fake present. Therefore, it should also mark the lack of exclusion. However, the use of present tense in fictional narratives does not suspend the fiction; for instance, despite the use of the present, (37) can still be a regular fictional discourse that excludes w@ from the worlds it is about.

-

(37)

Mia sitzt am Fenster und seufzt. Es regnet …

Mia sit:prs at the window and sigh:prs it rain:prs …

›Mia is sitting at the window sighing. It is raining …‹

In other words, it is probably impossible to derive whether a text is fiction or not from its morphological features (at least for German).

A third problem is that fake past and fiction instantiate very different types of distance from the actual world. Fake past conveys a distance from w@ that pertains to a speaker’s belief about w@ and that is gradual due to uncertainties of the speaker (see Schulz 2014 for details on the role of epistemically optimal worlds in CFs). Fiction, by contrast, conveys a distance from w@ that does not pertain to the belief (of the author) about w@ in a comparable way. The distance in this case is categorical, as the fiction is not the reality, independently of whether the fictional propositions are true in w@ or not.Footnote 20

This intuitive distinction between both types of distance can be confirmed by several linguistic observations. For one, recall that the counterfactual implicature introduced by CFs can be made explicit, as in (38) (= (32)).

-

(38)

Wenn Mia einen Hund hätte, wäre sie glücklich. Aber sie

if Mia a dog have:pst:sbjv be:pst:sbjv she happy but she

hat keinen Hund.

have:prs no dog

›If Mia had a dog, she would be happy. But she does not have a dog.‹

Fictional narratives, however, cannot create a true alternative to the fiction within the fiction. In sharp contrast to (38), examples such as (39) are clearly inconsistent.Footnote 21

-

(39)

#Mia saß am Fenster und seufzte. Aber Mia {sitzt / saß}

Mia sit:pret at the window and sigh:pret but Mia {sit:prs / sit:pret}

nicht am Fenster und {seufzt / seufzte}.

not at the window and {sigh:prs / sigh:pret}

›Mia was sitting at the window sighing. But Mia {is / was} not sitting at the window sighing.‹

Furthermore, text-external objections to some fictional truth are infelicitous as well. For instance, if A and B received a fictional discourse such as (40) and A responded to this by (41a), B would probably be irritated and thus utter (41b). In other words, taken as a sincere response, the text-external objection by A leads to the conclusion that A misconceives the crucial point of fiction.

-

(40)

Kohl seufzte. Er hatte von Napoleon geträumt.

Kohl sigh:pret he have:pst about Napoleon dream:ptcp

›Kohl sighed. He had dreamed about Napoleon.‹

-

(41)

-

a.

A: »How should one know? That’s nonsense!«

-

b.

B: »Eh? But that doesn’t matter; it’s fiction!«

-

a.

Another difference arises with regard to the handling of factual information. CFs are infelicitous in contexts where the speaker knows that the antecedent is true, as in (42).

-

(42)

-

a.

Context: Speaker finds out that Mia has a dog:

-

b.

#Wenn Mia einen Hund hätte, wäre sie glücklich.

if Mia a dog have:pst:sbjv be:pst:sbjv she happy

›If Mia had a dog, she would be happy.‹

-

a.

This is again different for fictional narratives. They can integrate facts of the actual world. The transfer to fiction just renders the distinction between ±factual essentially irrelevant. For instance, if (43) is used as part of a newspaper report, ±factual in the actual world is surely relevant. If the same sentence is used as part of a fictional narrative, its being true or false in the actual world does not bear on the felicity conditions of the fiction. That is, the fiction would clearly not become infelicitous once we must assume that the author in fact knows that Kohl went up to Mitterand.

-

(43)

Kohl ging auf {Mitterand / Napoleon} zu.

Koch go:pret to {Mitterand / Napoleon} up

›Kohl went up to {Mitterand / Napoleon}.‹

Finally, the standard temporal reading of the preterit has different effects on conditionals and fiction. In conditionals, the use of a temporal preterit yields so-called factual conditionals, as in (44). Factual conditionals do not exclude the actual world from the worlds they are about; the temporal reading thus automatically suspends the modal effect of CFs, which is expected, as the exclusion feature cannot operate on both the temporal and the modal domain.

-

(44)

Wenn Ben gestern in Rom war, ist er vermutlich heute

if Ben yesterday in Rome be:pret be:prs he presumably today

in Mailand.

in Milan

›If Ben was in Rome yesterday, he is presumably in Milan today.‹

By contrast, the example in (45) shows that a temporal reading of the preterit within fiction does not suspend the fiction. Specifically, the temporal forms in the second clause are related to Ben’s past and thus interpreted in a temporal way. However, this does not affect the fictional character of the narrative as a whole.Footnote 22

-

(45)

Ben dachte über den Tag zuvor nach. Nachdem er geputzt

Ben think:pret about the day before after he clean:ptcp

hatte, war er im Garten. Dann …

have:pst be:pret he in the garden then …

›Ben was thinking about the day before. After he had finished cleaning, he was in the garden. Then …‹

In sum, upon closer scrutiny, it turns out to be false that there is a close link between the epic preterit as a local morphological category and the marking of fiction as a global feature of a narrative as a whole.

4.2 The epic preterit as an instruction to imagine from a distance

The previous section has shown that the epic preterit does not contribute a distance feature that marks fictionality. In light of the imagination-based approach to fictional narratives as sketched in Section 3, I propose as an alternative that the epic preterit marks imagination from a distance. That is, it instructs an interpreter of a fictional sentence to imagine the situation that the sentence is about in a way as if she were not part of this situation.

To illustrate, let (46) be the beginning of a speaker-neutral narrative that an interpreter is reading and that she acknowledges as fiction.

-

(46)

Ben saß am Schreibtisch. Es regnete.

Ben sit:pret at the desk it rain:pret

›Ben was sitting at the desk. It was raining.‹

According to the imagination-based approach to fiction, the interpreter is invited to imagine a context with a topic situation in which there is a person called Ben sitting at a desk while it is raining. The proposed semantics of the epic preterit adds to this the constraint that the interpreter should not imagine being part of this topic situation. In other words, the interpreter remains an observer from the outside of the situation that she is invited to imagine. More formally, this can be implemented by the representation in (47).

The anch-component in this case captures that the narrative r about context c is anchored to the actual world in virtue of being read by an interpreting I (= i) at her now (= ni). As outlined in Section 3, c is existentially bound to the imag-component. As we assume that (46) is a speaker-neutral narrative, c does not contain any narrator-related pieces of information (that is, it lacks the components of (28) that are marked by ⌜⌝). However, it contains the following information. There is a topic situation s* that is part of c, an event e′ of some y called Ben sitting at the desk, and a raining event e″. Furthermore, the time of the topic situation s* is a subinterval of both event times, which follows from the plausible assumption that the aspect in (46) is imperfective. The crucial condition is the final condition, which captures the semantics of tense as contributed by the preterit. This condition says that, semantically, the preterit contributes distance between two underspecified variables, namely, a variable f (s*) that is determined by a variable function f applied to the topic situation s* and an indexical variable vindex. This echoes the standard assumption that tense relates a topic constituent to an indexical. The variables must be specified by context-dependent conceptual means, which I will discuss in more detail next.

I suggest that there are two principled options for the specification, as sketched in (48). In a nutshell, the temporal preterit is based on distance in the temporal domain, while the atemporal preterit is based on distance in the spatial domain.Footnote 23

-

(48)

-

a.

distal(f(s*), vindex) \(\leadsto\) <(τ(s*), ni) (temporal preterit)

-

b.

distal(f(s*), vindex) \(\leadsto\) ¬overlap(σ(s*), pi) (atemporal preterit)

-

a.

The option in (48a) corresponds to the usual temporal reading of the preterit. The distance is resolved to temporal precedence <, f is the time function singling out the topic time, and vindex is identified with a relevant now. Usually, this now would be the time of a speaker’s utterance. That is, if the fictional narrative licensed a narrator in the imag-component, the now would be identified with the narrating time, yielding the standard conception of fictional narratives with a retrospective narrator. For (47), however, there is no narrating situation in the imag-component (as we assume a speaker-neutral fictional discourse). Therefore, the only indexical time available is the now of the interpreter ni. The interpreter would thus be instructed to imagine that the topic situation the narrative is about occurred before her actual now while reading. I assume that this is a particularly feasible option for fictional narratives that are clearly related to former times. In many cases, however, the relation of the fictional content to the actual timeline does not play any crucial role; as a consequence, the temporal reading in (48a) is not used.

The alternative option in (48b) implements the idea that the preterit can license imagination from a distance without involving time features. Its set-up is analogous to the temporal reading, but it operates on spatial instead of temporal parameters. Specifically, the distance is resolved to the negation of a spatial overlap. Correspondingly, σ is the space function singling out the space that is occupied by the topic situation s*, and vindex is identified with the place pi where the interpreter i herself is located. As desired, the interpreter is thus instructed to look at the topic situation from the perspective of a physically distant observer who is not participating in this situation. Notably, according to this specification, the preterit has a very light function. It merely concerns a certain perspective on the scenario that is described. Furthermore, I consider this perspective the unmarked case in fictional narratives, simply because the interpreter usually takes for granted that she is not part of fictional situations.

The given analysis has the following merits. The effects of the preterit are kept within the scope of the imagination component. This is in line with the observations in Section 4.1, according to which the preterit is a local morphological category that does not bear on the global question of whether a narrative is fictional or not. In particular, the analysis thus also complies with temporal readings of the preterit within the fiction. In addition, it inspires a promising take on the effects of present tense within fiction. Recall from Section 4.1 that the use of an atemporal present in a narrative does not suspend its fiction, which is arguably a major obstacle to the idea that the atemporal preterit marks fiction. By contrast, the imagination-based approach to the atemporal preterit suggests a plausible analysis of the atemporal present as well. It simply instructs an interpreter to imagine the relevant topic situations not from a distance, but in a way as if she were part of them. In other words, the interpreter is invited to experience the situations that are described from their inside. This complies with the common intuition that the use of present tense in narratives creates the impression of immediate perception.

5 Conclusion

This paper has been concerned with the distinction between narrator-creating and narrator-neutral fictional narratives from a linguistic perspective. As a first step, I have argued against the proposal by Eckardt (2015), according to which fictional narratives always involve a narrating situation with a narrator, while the impression of narrator-neutral narration can be traced back to a lack of knowledge about this situation. Three problems have been presented. For one, it remains unclear why a lack of knowledge about the narrator should advance the impression of its nonexistence. Furthermore, the narrating instance is potentially abstract and thus at odds with the role of an ordinary speaker within the story. Finally, the preterit in German can receive an atemporal interpretation along the lines of the epic preterit as introduced by Hamburger (31977), which avoids the logical need for a narrating time and thus a narrator within the fiction.

As a second step, I have proposed an imagination-based account of narrator-neutral narration. This alternative account combines ideas from the Institutional Theory of Fiction as defended by Walton (1990) and Köppe/Stühring (2011) with the formal tools of Attitude Description Theory as developed by Maier (2017). Correspondingly, fictional narratives are conceived of as invitations to an update of the imagination component of the mental state of an interpreter. The distinction between narrator-creating and narrator-neutral narration is captured by optional existential binding of a narrating situation and a narrator within this imagination component.

As a third step, I have tackled the grammatically crucial follow-up question of which role the preterit in fictional narratives plays for the proposed account. I have confirmed the general idea that the preterit in German contributes a distance feature that can be resolved either temporally or atemporally. However, in contrast to the suggestion by traditional German linguistics, the atemporal reading of the preterit cannot be treated as a grammatical marker for fiction. Specifically, as shown by a detailed comparison between the epic preterit on the one hand and fake tense as known from counterfactuals on the other, fictionality should be considered a global text feature that does not interact in any reliable semantic way with local morphology. Finally, I have proposed an alternative imagination-based approach to the contribution of the epic preterit. In lieu of marking the fiction, it marks the way in which the contents of a fictional narrative should be imagined, namely, it instructs interpreters to imagine the situations the narrative is about from the perspective of a distant observer.

Notes

The idiomatic translations are mine. If reasonable, I dispense with word-by-word glosses in long examples for the sake of readability.

Relevant expectations can vary between, for instance, recipients (children will have different expectations than adults, etc.) or types of fiction (fairytales involve different expectations than historical novels, etc.). Such details will not be important here; see Lewis (1978) and Bonomi/Zucchi (2003) for discussion.

According to this standard set-up, the contents of fictional texts are modeled in terms of sets of contexts. It is controversial whether this is a fully intuitive conception. It seems to be more realistic that interpreters have a particular context in mind, which is, then, enriched step by step by the contents the story provides. This controversy is not crucial for the present paper; notably, however, the approach that will be proposed in Section 3 will rely on the imagination of particular contexts and thus on the more realistic conception of interpretation.