Abstract

Population ageing requires an understanding of the factors that enhance optimal functioning in later life. Moreover, for individual and societal well-being it demands a more balanced view of the ageing process that also accentuates human capital and realisation of potential. This study therefore explored the relationships between strengths use, mental well-being, meaning in life, self-perceptions of ageing, and socio-demographic characteristics of older adults. The study sample consisted of 88 older individuals (ages 55–88 years) who completed the following measures: Strengths Use Scale, Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale, Meaning in Life scale, and Attitude Toward Own Ageing. An open-ended question was added to explore contextual factors that may enable older adults to use their strengths more. Correlation analyses showed that greater strengths use was associated with higher levels of mental well-being in older individuals. Hierarchical regression analysis revealed strengths use as a significant predictor of mental well-being. Participants with more positive self-perceptions of ageing were applying their strengths to a greater extent. Although self-perceptions of ageing was not an additional predictor of strengths use. Furthermore, mediation analyses showed a significant and large indirect effect of strengths use on mental well-being through meaning in life. Various contextual factors such as appreciation of older adults and opportunities for work and engagement have been indicated as avenues to support greater strengths use. Results suggest that practicing strengths is important for positive mental health and the process of ageing well. Strategies to enhance greater strengths use in the ageing population are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychology and gerontology have been undergoing a transformation from a deficit-model to a focus on strengths and resources. Positive ageing as an emerging topic within positive psychology, is concerned with identifying factors that enhance well-being in old age (Vaillant, 2004). In the scientific literature, different terms on positive ageing are employed and similarly focus on optimal human functioning in late life.

While in the past, ageing had been considered merely as a physiological process of inevitable decline, it is recognised today that it necessitates an examination of social, psychological and biological influences and their interplay in order to understand the factors that promote optimal functioning in old age (Bengtson et al., 2009; Levy, 2009). Equal importance should be given to the interrelationships between older persons and their environments for the study of the human ageing process (Gans et al., 2009).

Even though great emphasis has been placed on the problems and pressures of an ageing society, there is a growing recognition that the positive potential of an ageing population has been disregarded and greater importance should be placed on the human capital of older adults for society (Rowe & Kahn, 2015). Moreover, it is argued that for the future well-being and prosperity of societies, it is vital that individuals are enabled to fulfil their potential throughout their life span (UK Government Office for Science [GO-Science], 2008). In a similar vein, Ranzijn (2002) postulates “a positive psychology of ageing”(p. 79) that views older adults as a resource and empowers them to express their talents, skills, and competencies. Conversely, ageism and negative age stereotyping have been identified as major obstacles to the realisation of older adults’ potential (Huppert, 2005). But also how older persons perceive their own ageing process has influence on their behaviour, cognition, or functioning (Levy, 2003, 2009). It is argued that the under-utilisation of older persons’ capabilities and experience can be detrimental to their mental well-being and the maintenance of their mental capacities (GO-Science, 2008).

Consequently, greater emphasis on the strengths of older adults as well as a deeper understanding of the factors that promote mental well-being in late life seems to be crucial. Human strengths highlight assets and positive attributes of individuals and enable self-expression, fulfilment of potential, and well-being (Linley, 2013). Strengths of character most strongly related to life satisfaction were also associated with all three orientations to happiness that include pleasure, engagement, and meaning and constitute the full life (Peterson, Ruch, Beermann, Park, & Seligman, 2007). Due to increased life expectancy the post retirement phase can extend over two or even three decades which might offer an unique opportunity for older individuals to be productive, fulfil unrealised potential, and engage in personal meaningful endeavours. Furthermore, generativity, the concern and care for younger generations, seems to be a salient theme, not only in midlife, but also in later life. The expression of generativity is associated with mental well-being and flourishing (McAdams, 2013) and is a strong predictor of meaningfulness (Schnell, 2011).

This study therefore aims to investigate the relationships of strengths use, mental well-being, meaning in life, and self-perceptions of ageing. In the following section a theoretical and conceptual understanding of the main variables used in this study and their importance in regards to a positive ageing experience will be presented.

Strengths Use

Human strengths as major theme of positive psychology emphasise positive characteristics of people and enable individuals to grow and flourish. Within the field of positive psychology two main conceptualisations of strengths exist. First, the Values in Action (VIA) classification of character strengths and virtues (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) is a widely used taxonomy of strengths and encompasses 24 universally held character strengths that are assigned to six core virtues. Character strengths are morally valued aspects of personality and components of the good character that contribute to positive development throughout the life span (Park & Peterson, 2009; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Second, Linley (2008) provided a more comprehensive definition of a strength that is “a pre-existing capacity for a particular way of behaving, thinking, or feeling that is authentic and energising to the user, and enables optimal functioning, development and performance” (p. 9). This study employs the term strengths in this more generic sense in order to cover a wider spectrum of existing strengths as opposed to a restricted number. Broad empirical evidence from cross-sectional, longitudinal and experimental studies indicate that strengths use is associated with different types of well-being and further valued outcomes such as achievement, self-esteem, subjective vitality, and decreases in depression (see reviews by Linley, 2013; Niemiec, 2013).

Research findings document that strengths use was a unique predictor of students’ subjective well-being (Proctor et al., 2011) and significantly positively related to psychological well-being in a sample of college students (Govindji & Linley, 2007). Furthermore, greater generic use of strengths has been found to lead to higher levels of well-being over time in an adult sample (Wood et al., 2011). In an occupational context, deploying character strengths was linked to greater well-being through an increased sense of meaning in life (Littman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010).

Given that previous studies have found positive associations between generic strengths use and well-being in younger samples, an investigation of this relationship in a sample of older persons might be worthwhile for a greater understanding of the factors that enhance well-being in older age. Furthermore, research on generic strengths use and well-being is rare as most studies have investigated character strengths in this regard (Proctor et al., 2011). Empirical research has predominately examined strengths in relation to subjective well-being and to a lesser extent to psychological well-being (Linley, 2013).

Mental Well-Being

In policy and academic literature, the terms positive mental health and mental well-being are often used as synonyms. Mental well-being is described as a positive state in which individuals are able to use their abilities, contribute to society, cope with challenges, and maintain positive relationships (GO-Science, 2008; World Health Organization [WHO], 2004). Positive mental health includes both hedonic and eudaimonic components that relate to positive feeling and optimal functioning (Huppert & So, 2013). Research shows that individuals who pursue both approaches to happiness experience the highest levels of well-being (Huta & Ryan, 2010). The concept of positive mental health is raising increased interest since research documents its beneficial effects on health and social outcomes. Research findings indicate that individuals with high levels of positive mental health reported the fewest chronic physical conditions and that positive mental health acts as a protective factor in ageing (Keyes, 2005). Evidence from longitudinal data demonstrates that individuals with high psychological well-being reported better physical health after a decade than those with consistent low well-being (Ryff et al., 2015). Furthermore, it is recognised that not only impaired well-being is a risk factor for depression, but that the absence of positive well-being in older adults increases the risk of becoming depressed at a later stage (Wood & Joseph, 2010). To date, however, the promotion of older adults’ well-being seems to be a neglected area (Huppert, 2014).

Meaning in Life

According to the psychosocial theory of personality development, later adulthood is characterised by the need to practice generativity and make meaning of one’s life in order to achieve integrity and maturity (Erikson, 1959/1980). Meaning in life is a fundamental topic in positive psychology as it determines to a large extent positive outcomes in domains such as well-being, physical health, resilience, or successful ageing (Wong, 2012). However, there is no single definition of meaning in life. This study uses Krause’s (2004) conceptualisation that comprises four dimensions: having a value system, a sense of purpose, goals, and being able to reconcile the past. Presence of meaning in life is associated with positive affect, higher life satisfaction, greater optimism (Steger et al., 2006; Park et al., 2010), better psychological well-being (Zika & Chamberlain, 1992), and better physical health (Krause, 2004; Pinquart, 2002). Specifically, purpose in life as a component of meaning, is related to various positive health outcomes. For example, higher levels of purpose in life were linked to longevity (Boyle et al., 2009), a reduced risk of disability in older persons (Boyle, Buchman, & Bennett, 2010), and a reduced risk of Alzheimer disease in old age (Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, & Bennett, 2010).

Self-Perceptions of Ageing

The trajectory of self-perceptions of ageing starts early in life and runs from society to the individual. Internalised ageing stereotypes are reinforced in adulthood and become ageing self-stereotypes in older age (Levy, 2003). Across various areas of science, research findings demonstrate the beneficial impact of positive attitudes towards ageing on different outcome measures. Older individuals’ attitude toward ageing can have an influence on their memory performance (Levy, 1996), health (Levy et al., 2000), physical functioning (Sargent-Cox et al., 2012), and longevity (Levy et al., 2002). A meta-analysis of 19 longitudinal studies revealed a small significant effect of attitudes towards own ageing on health, health behaviour, and survival (Westerhof et al., 2014). In contrast, negative age stereotypes have detrimental effects on elders’ well-being and capabilities and hinder the realisation of their potential (Huppert, 2005; GO-Science, 2008). It would therefore be worthwhile to investigate how self-perceptions of ageing relate to strengths use. To our knowledge, there is no study that has explored the relationship of these two variables.

Aims and Hypotheses

Population ageing calls for a scientific understanding of the factors that facilitate ageing well and enhance mental well-being in old age. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the relationships between strengths use, mental well-being, meaning in life, and self-perceptions of ageing in older adults. As far as we know, these relationships have not been examined in a sample of older persons to date. Based on the theoretical rationale and previous research, this study explored the following hypotheses:

H1a) Higher strengths use is associated with greater mental well-being in older adults.

H1b) Strengths use positively predicts mental well-being.

H2a) More positive self-perceptions of ageing are linked to greater strengths use.

H2b) Self-perceptions of ageing positively predicts strengths use.

H3 Meaning in life acts as an intervening variable between strengths use and mental well-being.

Given that later life is characterised by the loss of significant roles, the transition to retirement, and declines in purpose in life, the question arises whether older adults have sufficient opportunities for deploying their strengths. Not only internal barriers, such as negative self-perceptions of ageing, might prevent older persons from using their strengths, but also external circumstances might influence the extent to which older adults are able to use their strengths. Consequently, this study will also explore contextual factors that would enable greater strengths use in older adults.

Methods

Design

For this study a quantitative research design was chosen to test the hypotheses at the within subjects level. As contextual factors can expand or restrict opportunities for strengths use (Biswas-Diener et al., 2011; Littman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010; Lopez et al., 2003) an open-ended question was added in order to explore its interrelationship between the ageing individual and the environment. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate facilitating and constraining factors that have impact on the strengths use of older adults. Participants’ personal perspectives were expected to provide valuable indications either on restrictions they face for using own strengths or on measures for greater support. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously.

Procedure

Ethical approval for the study was provided by the University’s Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited through terzStiftung, a Swiss foundation advocating for the concerns of older people and dedicated to assisting science and economy in supporting intergenerational solidarity. The foundation has a pool of participants for market research and studies. In a first wave, participants from this pool (N = 315) and in a second wave benefactors of the foundation (N = 931) aged 55 and above were invited to take part in the study through email. A hyperlink directed them to the online questionnaire. Participants were informed about the purpose and content of the study with an invitation letter and completed an online informed consent process. Sociodemographic questions were answered first. At the end of the questionnaire and as part of the debriefing, participants were able to download an information leaflet on the topic of health promotion in older age. Of the invited individuals, 117 responded to the online questionnaire (response rate = 10%). The final sample comprised 88 participants since 29 had to be excluded due to incomplete data.

Participants

Participants in the study consisted of 52 men and 36 women (mean age, M = 70.26; SD = 6.69, range 55–88 years) living in Switzerland. Of the sample 60% of the participants were married, 22% divorced, 10% single, and 8% widowed. Approximately 36% held a university degree, 26% held a diploma of professional education, 11% held a baccalaureate, 24% had a vocational education and training, and 2% had a compulsory school qualification (9-year education). More than half of the sample (62.5%) was involved in one or more of the following activities: full- or part-time employment, secondary employment, volunteering or civic engagement, whereas 37.5% stated that they were solely retired. The majority (90%) considered their income as sufficient to meet their needs. Of that sample, 55% were not practitioners of any religion. Self-rated health was stated by 22% of the participants as very good, 57% as good, 20% as fair, and 1% as poor. Most of the participants (81%) did not report depressive mood or loss of interest, 10% gave a positive response to one of the two items, and 9% to both items. Two participants had a missing value in the age variable and one participant in the religion variable.

Measures

Published German translations of mental well-being and self-perceptions of ageing scales were used. For the two remaining questionnaires, the measures were translated into German and then translated back into English to verify conformity with the original versions.

Main Variables

Strengths Use

The Strengths Use Scale (SUS; Govindji & Linley, 2007) is a relatively new 14-item scale designed to explicitly measure strengths use. Respondents rate the extent to which they use their strengths in different settings. Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) with higher scores indicating greater strength use. In regard to the selected sample which included retirees, one item had to be adjusted from “My work gives me lots of opportunities to use my strengths” to “My daily activities give me lots of opportunities to use my strengths”. Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.95. The authors of the measurement in a study with a sample of college students reported exactly the same reliability. A clear one-factor structure as well as good concurrent and predictive validity of the original scale was reported by Wood and Joseph (2010). The scale positively correlated with well-being, self-esteem, vitality and positive affect and negatively correlated with negative affect and stress at baseline and at later time.

Mental Well-Being

The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS; Tennant et al., 2007) is a measure at the population level that assesses different facets of positive mental health. The scale covers hedonic and eudaimonic aspects and comprises 14 items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Representative items include “I have been feeling optimistic about the future” and “I have been feeling useful”. In the present study, reliability was high (α = 0.93) and comparable with the α = 0.91 reported by the original authors in a population sample.

Meaning in Life

The Meaning in Life scale was specifically devised to assess meaning among older adults (Krause, 2004). Participants responded to a 14-item scale that measures meaning in life as a multidimensional construct encompassing four dimensions: values, purpose, goals and reflection on the past. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (disagree strongly) to 4 (agree strongly). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.91.

Self-Perceptions of Ageing

Self-perceptions of ageing were measured with the 5-item Attitude Towards Own Aging subscale of the Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale (Lawton, 1975). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale, from 1 (does not apply at all) to 4 (fully applies). Two items were reverse scored. Higher scores are indicative of more positive attitudes toward ageing. Cronbach’s alpha for this study was 0.72.

Qualitative Question

The open-ended question was voluntary and was stated as follows: “Which form of support through the wider community would facilitate and promote the use of your strengths?”

Socio-Demographic Variables

-

Sex was scored in a binary format.

-

Age was assessed continuously in years.

-

Marital status was measured in a categorical variable with four groups: single, married, widowed, divorced.

-

Education was assed as a categorical variable with five defined groups. For the multiple regression analyses this variable was transformed into a dichotomous variable. Participants were categorised as either secondary education (including compulsory school, vocational education and training, baccalaureate schools) or tertiary education (including professional education and training colleges, universities and universities of applied science).

-

Work status. Multiple answers were possible within four defined categories. These categories were dichotomised into working (including full or part time work, secondary employment, volunteering or civic engagement) or retired (participants who only selected that category).

-

Income was measured by the question: “Is your income sufficient to meet your needs?” (yes/no).

-

Religion was assessed by the question: “Are you a practitioner of any religion?” (yes/no).

-

Self-rated health was rated as a categorical variable. For the multiple regression analyses this variable was transformed into a dichotomous variable: good health (including those who rated their health as very good and good) or poor health (including those who rated their health as fair, poor, or very poor).

-

Depressive symptoms were assessed with two questions: During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?” (PRIME-MD; Spitzer et al., 1994). A negative response to the two items makes depression highly unlikely, whereas a yes answer to one of the items is considered a positive screening test result (Spitzer et al., 1994; Whooley et al., 1997). A new continuous variable was created with the mean of both scores.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20 for Mac. Descriptive statistics and normality tests were performed on the data prior to running the analyses. Bivariate relationships between socio-demographic variables and main variables were computed. Independent samples t-test were conducted for the variables sex, work status, income, and religion. For the variable marital status, one-way analysis of variance was performed. A Pearson correlation for the variable age and Spearman’s rho for the variables education and health status were conducted. Pearson correlations were also conducted to examine the relationships between the main variables. To further test the hypotheses two hierarchical regression analyses and a mediation analysis were performed.

Qualitative data were analysed using conventional content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) that included the following consecutive steps: detecting emerging topics, forming codes and generating themes.

Results

Bivariate Relationships

Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Main Variables

For sex, age, marital status, education, work status, no statistical significant relations were found except for age and mental well-being, r = .24, p = .029, level of education and strengths use, r = .29, p = .005, meaning in life, r = .25, p = .021, and self-perceptions of ageing, r = .34, p < .001. Levene’s test for income in relation to strengths use and meaning in life was significant, but the t-test on equal variances not assumed was non-significant. However, the group difference in terms of strengths use represents a medium-sized effect, d = 0.43. Levene’s test and the t-test for income in relation to mental well-being was non-significant. Participants who considered their income as sufficient had more positive self-perceptions of ageing. This difference was significant t(86) = 3.39, p < .001. No significant mean difference was found for religion, although the group difference in regards to meaning in life represents a small- to medium-sized effect, d = 0.37. Poor health was significantly negatively related to mental well-being r s = −.36, p < .001 and self-perceptions of ageing r s = −.34, p < .001. Absence of depressive symptoms was significantly positively correlated with strengths use r = .35, p = .001, mental well-being r = .51, p < .0001, meaning in life r = .35, p = .001, and self-perceptions of ageing r = .48, p < .0001.

Main Variables

As shown in Table 1, all main variables were significantly correlated. Strengths use, meaning in life, and self-perceptions of ageing had a large positive correlation with mental well-being. Strengths use and mental well-being were significantly related and therefore confirming hypothesis 1a). Self-perceptions of ageing were significantly related to strengths use which indicates that hypothesis 2a) was supported.

Regression Analyses

Strengths Use Predicting Mental Well-Being

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to assess whether strengths use predicted mental well-being. Highest education level achieved, income, health status, and depressive symptoms were entered in the first block for statistical control. For the second block the first two predictor variables, meaning in life and self-perceptions of ageing, were selected for entry. Strengths use was entered in the final block to evaluate whether it made an additional contribution.

Results of descriptive statistics, VIF values, and Eigenvalues gave no concern for multicollinearity. The value of the Durbin Watson statistic was 1.873, therefore the assumption that errors are independent was not violated. ANOVA tests showed that the model was a significant fit of the data. There was no undue influence of individual cases on the model. Values of Cook’s distance were below 1 (mean = .02, minimum = .00, maximum = .84).

As shown in the Table 2, the first model revealed that the selected socio-demographics accounted for 26.7% of the variation in mental well-being, R 2 = 0.27, F (4,83) = 7.57, p < .0001. For this model, depressive symptoms was the only significant predictor of mental well-being, t(83) = 4.32, p < .0001. When the variables meaning in life and self-perceptions of ageing were added in the second block, they accounted for an additional 30.4% of the variance, R 2 change =0.30, F (2,81) = 28.75, p < .0001. For the second model, depressive symptoms, t(81) = 2.46, p = .016, meaning in life t(81) = 5.15, p = .000, and self-perceptions of ageing, t(81) = 2.17, p = .033, were all significant predictors of mental well-being. The addition of strengths use to the final model accounted for an additional 5% of the variance, R 2 change =0.05, F (1,80) = 9.61, p = .003. In the final model, depressive symptoms, t(80) = 2.40, p = .019, meaning in life, t(80) = 3.60, p < .001, and strengths use, t(80) = 3.10, p = .003 were significant predictors of mental well-being. Consequently, lower levels of depressive symptoms and higher levels of meaning in life as well as greater strengths use predicted mental well-being.

Self-Perceptions of Ageing Predicting Strengths Use

A second hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to investigate whether self-perceptions of ageing predicted strengths use. The selected socio-demographic variables were entered in the first block for statistical control. Mental well-being and meaning in life were entered in the second block. The variable self-perceptions of ageing was introduced in the final block to test whether it was a significant predictor of strengths use.

Results of the descriptive statistics, VIF values and Eigenvalues gave no concern for multicollinearity. The value of the Durbin Watson statistic was 2.165, therefore the assumption that errors are independent was not violated. ANOVA tests showed that the model was a significant fit of the data. There was no undue influence of individual cases on the model. Values of Cook’s distance were below 1 (mean = .02, minimum = .00, maximum = .43).

As can be seen from Table 3, the first model accounted for 15% of the variance in strengths use, R 2 = 0.15, F (4,83) = 3.61, p = .009. Depressive symptoms was the only significant predictor for strengths use in this model, t(83) = 2.46, p = .015. Mental well-being and meaning in life were introduced in the second block and accounted for an additional 33% of the variance, R 2 change =0.33, F (2,81) = 25.45, p = .000. In this model, mental well-being, t(81) = 3.46, p = .001 and meaning in life, t(81) = 2.78, p = .007, were significant predictors of strengths use.

The final model did not significantly contribute to the prediction of strengths use, accounting for 1% of the variance, R 2 change =0.01, F (1,80) = 1.28, p = .261. Therefore, the variable self-perceptions of ageing, t(80) = 1.13, p = .261 was not a significant predictor of strengths use.

Mediation Analysis

Meaning in Life as an Intervening Variable between Strengths Use and Mental Well-Being

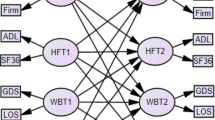

Mediation was tested by assessing the size of the indirect effect and its confidence interval using the measure kappa-squared (κ 2; Preacher & Kelly, 2011). There was a significant indirect effect of strengths use on mental well-being through meaning in life, b = 0.151, 95% BCa CI [0.072, 0.252]. This represents a large effect, κ 2 = .282, 95% BCa CI [.150, .429]. Hypothesis 3 was therefore confirmed. Figure 1.

Content Analysis

The optional open-ended question was answered by 66 participants. 18 responses had to be assigned to the theme uninterpretable as those participants did not understand the question or their answer could not be interpreted and 6 were assigned to the theme miscellaneous. Final results yielded five major themes. Table 4 displays the emerging themes, frequencies and percentage of responses, and example answers.

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship of strengths use, mental well-being, meaning in life, and self-perceptions of ageing in a sample of older adults aged 55 and above. Findings of this study indicated that strengths use was positively related to mental well-being, meaning in life, and self-perceptions of ageing.

The first hypothesis was supported as higher strengths use was significantly associated with greater mental well-being in older adults. Furthermore, strengths use was a significant predictor of mental well-being in the model. These findings are consistent with previous results regarding the positive association of strengths use with well-being in younger samples (Govindji & Linley, 2007; Proctor et al., 2011, Wood et al., 2011). This study extends previous research on strengths use in relation to well-being with findings in a uniquely older adult sample.

The first part of the second hypothesis was also confirmed: Older individuals who reported more positive self-perceptions of ageing were using their strengths to a greater extent. However, due to the cross-sectional design this relationship could also be bi-directional. Further investigations revealed that mental well-being and meaning in life predicted strength use, but self-perceptions of ageing were not a significant predictor of strength use in this model. Nevertheless, the aforementioned positive correlation points out that positive self-perceptions of ageing might be important for the realisation of potential (Huppert, 2005) and influence further development in old age through cognitive and behavioural pathways (Westerhof et al., 2014).

The hypothesised mediating relationship between strengths use and mental well-being via meaning in life was supported. Thus, the relationship between greater strengths use and higher levels of mental well-being can partly be explained by an enhanced sense of meaning in life. These findings support and extend previous research that has examined a similar mediation model including character strengths in a occupational context within an adult sample (Littman-Ovadia & Steger, 2010). As meaning in life plays a crucial role in shaping the mental well-being of older adults, the study findings demonstrate that strengths use may serve to enhance a sense of meaning in life. This result may be of particular relevance, as purpose in life seems to decline with ageing (Ryff, 1995).

The relationships between socio-demographic and main variables were also examined. However, a detailed discussion would go beyond the scope of this paper. Participants with higher levels of education used their strengths to a larger degree, reported greater meaning in life, and had more positive self-perceptions of ageing. Income had an effect on strengths use. This could mean, that older adults with sufficient income may have more opportunities presented to deploy their strengths. The findings also showed a significant relationship between sufficient income and more positive self-perceptions of ageing. Obviously, financial security in old age permits individuals to enjoy their retirement, face the future with confidence, and pursue their interests. Older adults who reported better health had higher levels of mental well-being and more positive self-perceptions of ageing. The detrimental impact of depressive symptoms was also shown in this study. Participants who reported depressed mood or loss of interest, or both combined, used their strengths to a lesser extent, reported lower levels of mental well-being, less meaning in life, and fewer positive self-perceptions of ageing.

The open-ended question allowed participants to express themselves and give specific information on how they could be better supported in applying their strengths. Two basic groups could be identified. First, individuals who stated that they do not need any further support, and second, participants who expressed the desire for greater strengths support and submitted suggestions. Responses include older adults’ desire to feel valued as an older person as well as for own abilities, skills, and experiences, regardless of their chronological age. Furthermore, a number of participants perceived their opportunities as not sufficient to deploy own strengths and requested more occasions for work and meaningful engagement. Lastly, the desire to be generative and for intergenerational interactions was highlighted, which is consistent with the developmental task for adulthood identified by Erikson (1959/1980). Achieving generativity counteracts a sense of stagnation and is essential for late-life development. However, a lack of appreciation or perceived respect from the younger generations for their contribution can prevent older adults from pursuing generative goals (Cheng, 2009).

Fulfilling own potential, coping with adversities, and contributing to society are part of the conditions that describe mental well-being. The findings of this study are in line with this position as they underline the relevance of using strengths in later life, engaging in meaningful activities and cultivating positive attitudes toward ageing for the mental well-being in older persons. Pleasure, engagement, and meaning have been proposed as essential components of well-being (Seligman, 2002). Individuals scoring high on all three approaches to the good life, which characterises the full life, reported the highest level of life satisfaction (Peterson et al., 2005; Ruch et al., 2010). Later Seligman (2011) introduced the PERMA model of flourishing that consists of five elements: positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Using own strengths might contribute to all those dimensions, cover aspects of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being and thereby enable individuals to flourish across the life span.

Implications of Present Research

The quantitative and qualitative findings of the present study have implications at different levels of society. At the individual level, older adults could exercise influence over their own ageing process by engaging in meaningful activities and applying individual strengths. Practitioners and professionals adopting a strengths perspective might empower and assist older clients in understanding their strengths, finding a congruent role, and encourage greater strengths use. Moreover, health and ageing professionals should reflect on their attitudes toward older people as research demonstrates that age stereotypes and prejudices are prevalent even within this group (Pasupathi & Lockenhoff, 2002). At the societal and organisational level, the damaging effect of negative age stereotypes on the realisation of older adults’ potential should be recognised and replaced with more positive and realistic images of ageing. Only if prevailing age discrimination and age barriers are removed can older individuals enjoy equal opportunities (Walker, 2006). In addition to acknowledging, valuing, and maximising the human capital of older adults, the creation of meaningful tasks and roles for older citizens should be enhanced.

Limitations and Future Directions

Various limitations might impact the interpretation of these results. First, the relatively small sample used for this study may limit generalisability. Furthermore, the low response rate raises issues. A possible explanation might be the short time frame for replying to the questionnaire (1 month for the first group and 2 weeks for the second group). Although the pool of participants from the foundation could be considered as an adequate representation of older people in Switzerland, it is nevertheless a biased sample. In general, Internet samples are fairly diverse, albeit with a slight bias towards more educated and affluent people, as in this study (Gosling & Mason, 2015; Gosling et al., 2004). The two-item questionnaire to assess depressive symptoms was chosen due to its test characteristics comparable to other case-finding instruments as well as its brevity, especially in regard to an older target group. However, in light of the significant relationship between depressive symptoms and the main variables, the administration of a more extensive depression screening instrument could be an asset. In the present study the same Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 for the Strengths Use Scale was reported as in the study by the authors of the measurement. A high value of alpha may indicate redundancy among the items. A maximum value of 0.90 has been recommended (Streiner, 2003). It has to be noted that the lack of validation of the translated scale represents a further limitation. Another constraint of this study consists in the cross-sectional nature of the data that does not allow conclusions about causality and direction. Furthermore, study data came from self-reports measures that can be prone to errors (e.g. effects of social desirability). Finally, it should be noted that personality characteristics were not taken into account in this study. In effect, personality traits in early life are a predictor for the psychological well-being later in life (Abbott et al., 2008). Further studies might test the relationships among the variables with a larger sample and in other populations as the ageing experience might vary even within Western cultures (Westerhof & Barrett, 2005). A longitudinal design might provide further evidence on the relationship between strengths use and the mental well-being of older adults. Finally, in order to promote optimal functioning in later life, interventions that both encourage greater strengths use and positive attitudes towards ageing might be developed and evaluated.

Conclusion

The present study revealed how positive psychology can contribute to positive ageing through the concept of strengths. The findings of this study demonstrate the importance of practicing strengths for the mental well-being of older adults. Strengths use permits older individuals to feel authentic, derive meaning and purpose, and fulfil potential in later life. Moreover, a strengths approach respects the heterogeneity among elders as it enables older persons to contribute to the environment in many different ways and according to their capabilities. In view of the demographic age-shift, this study shed light on measures for enhancing positive mental health in old age and realising older adults’ potential for individual and societal benefit.

References

Abbott, R. A., Croudace, T. J., Ploubidis, G. B., Kuh, D., Wadsworth, M. E. J., Richards, M., & Huppert, F. A. (2008). The relationship between early personality and midlife psychological well-being: evidence from a UK birth cohort study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43, 679–687. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0355-8.

Bengtson, V. L., Gans, D., Putney, N. M., & Silverstein, M. (2009). Theories about age and aging. In V. L. Bengtson, D. Gans, N. M. Putney, & M. Silverstein (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (2nd ed., pp. 3–23). New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T. B., & Minhas, G. (2011). A dynamic approach to psychological strength development and intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6, 102–118. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.545429.

Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71, 574–579. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e318a5a7c0.

Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Barnes, L. L., & Bennett, D. A. (2010a). Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 304–310. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208.

Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2010b). Purpose in life is associated with a reduced risk of incident disability among community-dwelling older persons. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18, 1093–1102. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e318d6c259.

Cheng, S.-T. (2009). Generativity in later life: perceived respect from younger generations as a determinant of goal disengagement and psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 64B, 45–54. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbn027.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: Norton (Original work published 1959)

Gans, D., Putney, N. M., Bengtson, V. L., & Silverstein, M. (2009). The future of theories of aging. In V. L. Bengtson, D. Gans, N. M. Putney, & M. Silverstein (Eds.), Handbook of theories of aging (2nd ed., pp. 723–737). New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Gosling, S. D., & Mason, W. (2015). Internet research in psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 877–902. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015321.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., & Srivastava, S. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions. American Psychologist, 59, 93–104. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93.

Govindji, R., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Strengths use, self-concordance and well-being: implications for strengths coaching and coaching psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2, 143–153.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

Huppert, F. A. (2005). Positive mental health in individuals and populations. In F. A. Huppert, N. Baylis, & B. Keverne (Eds.), The science of well-being (pp. 305–340). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Huppert, F. A. (2014). The state of wellbeing science: concepts, measures, interventions and policies. In F. A. Huppert & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Interventions and policies to enhance wellbeing (6; 1–49). Chichester: Wiley.

Huppert, F. A., & So, T. T. C. (2013). Flourishing across Europe: application of a new conceptual framework for defining well-being. Social Indicators Research, 110, 837–861. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9966-7.

Huta, V., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Pursuing pleasure or virtue: the differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 735–762. doi:10.1007/s10902-011-9249-7.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Chronic physical conditions and aging: is mental health a potential protective factor? Ageing International, 30, 88–104. doi:10.1007/BF02681008.

Krause, N. (2004). Stressors arising in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 59B, 287–297. doi:10.1093/geronb/59.5.S287.

Lawton, M. P. (1975). The Philadelphia geriatric center morale scale: a revision. Journal of Gerontology, 30, 85–89. doi:10.1093/geronj/30.1.85.

Levy, B. R. (1996). Improving memory in old age through implicit self-stereotyping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 1092–1107. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1092.

Levy, B. R. (2003). Mind matters: cognitive and physical effects of aging self-stereotypes. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 58B, 203–211. doi:10.1093/geronb/58.4.P203.

Levy, B. R. (2009). Stereotype embodiment. A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 332–336. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x.

Levy, B. R., Hausdorff, J. M., Hencke, R., & Wei, J. Y. (2000). Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 55B, 205–213. doi:10.1093/geronb/55.4.P205.

Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Kunkel, S. R., & Kasl, S. V. (2002). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 261–270. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.83.261.

Linley, A. (2008). Average to a+: realising strengths in yourself and others. Coventry: CAPP Press.

Linley, A. (2013). Human strengths and well-being: finding the best within us at the intersection of eudaimonic philosophy, humanistic psychology, and positive psychology. In A. S. Waterman (Ed.), The best within us: positive perspectives on Eudaimonia (pp. 269–285). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Steger, M. (2010). Character strengths and well-being among volunteers and employees: toward an integrative model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 419–430. doi:10.1080/17439760.2010.516765.

Lopez, S. J., Snyder, C. R., & Rasmussen, H. N. (2003). Striking a vital balance: developing a complementary focus on human weakness and strength through positive psychological assessment. In S. J. Lopez & C. R. Snyder (Eds.), Positive psychological assessment (pp. 3–20). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

McAdams, D. P. (2013). The positive psychology of adult generativity: caring for the next generation and constructing a redemptive life. In J. D. Sinnott (Ed.), Positive psychology: advances in understanding adult motivation (pp. 191–205). New York: Springer.

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: research and practice (the first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: perspectives on positive psychology (pp. 11–30). New York: Springer.

Park, N., Park, M., & Peterson, C. (2010). When is the search for meaning related to life satisfaction? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2, 1–13. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0845.2009.01024.x.

Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Character strengths: research and practice. Journal of College and Character, 10(4). doi:10.2202/1940-1639.1042.

Pasupathi, M., & Lockenhoff, C. (2002). Ageist behavior. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 201–246). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: a handbook and classification. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Peterson, C., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Orientation to happiness and life satisfaction: the full life versus the empty life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6, 25–41. doi:10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z.

Peterson, C., Ruch, W., Beermann, U., Park, N., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2007). Strengths of character, orientations to happiness, and life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2, 149–156. doi:10.1080/17439760701228938.

Pinquart, M. (2002). Creating and maintaining purpose in life in old age: a meta-analysis. Ageing International, 27, 90–114. doi:10.1007/s12126-002-1004-2.

Preacher, K. J., & Kelly, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16, 93–115. doi:10.1037/a0022658.

Proctor, C., Maltby, J., & Linley, P. A. (2011). Strengths use as a predictor of well-being and health related quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 153–169. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9181-2.

Ranzijn, R. (2002). Towards a positive psychology of ageing: potentials and barriers. Australian Psychologist, 37, 79–85. doi:10.1080/00050060210001706716.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (2015). Successful aging 2.0: conceptual expansions for the twenty-first century. Journals of Gerontology Series B: psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 593–596. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv025.

Ruch, W., Harzer, C., Proyer, R. T., Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2010). Ways to happiness in German-speaking countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26, 227–234. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000030.

Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 99–104. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772395.

Ryff, C. D., Radler, B. T., & Friedman, E. M. (2015). Persistent psychological well-being predicts improved self-rated health over 9-10 years: longitudinal evidence from MIDUS. Health Psychology Open, 2(2). doi:10.1177/2055102915601583.

Sargent-Cox, K. A., Anstey, K. J., & Luszcz, M. A. (2012). The relationship between change in self-perceptions of aging and physical functioning in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 27, 750–760. doi:10.1037/a0027578.

Schnell, T. (2011). Individual differences in meaning-making: considering the variety of sources of meaning, their density and diversity. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 667–673. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.06.006.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: using the new positive psychology to realize your potential and for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., Kroenke, K., Linzer, M., DeGruy, F., Hahn, S. R., … Johnson, J. G. (1994). Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care. The PRIME-MD 1000 Study. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 1749–1756. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520220043029.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and the search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80.

Streiner, D. L. (2003). Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 80, 99–103. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., … Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63

UK Government Office for Science. (2008). Foresight mental capital and wellbeing: making the most of ourselves in the twenty-first century. Final project report. England: Author.

Vaillant, G. E. (2004). Positive aging. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 561–577). Hoboken: Wiley.

Walker, A. (2006). Active ageing in employment: its meaning and potential. Asia-Pacific Review, 13(1), 78–93. doi:10.1080/13439000600697621.

Westerhof, G. J., & Barrett, A. E. (2005). Age identity and subjective well-being: a comparison of the United States and Germany. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 60B, 129–136. doi:10.1093/geronb/60.3.S129.

Westerhof, G. J., Miche, M., Brothers, A. F., Barrett, A. E., Diehl, M., Montepare, J. M., … Wurm, S. (2014). The influence of subjective aging on health and longevity: a meta-analysis of longitudinal data. Psychology and Aging, 29, 793–802. doi: 10.1037/a0038016

Whooley, M., Avins, A. L., Miranda, J., & Browner, W. S. (1997). Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12, 439–445. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x.

Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Introduction. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: theories, research and applications (2nd ed., pp. xxix–xliv). New York: Routledge.

Wood, A. M., & Joseph, S. (2010). The absence of positive psychological (eudaimonic) well-being as a risk factor for depression: a ten year cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122, 213–217. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.032.

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Kashdan, T. B., & Hurling, R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: a longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 15–19. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.004.

World Health Organization. (2004). Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice: summary report. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Zika, S., & Chamberlain, K. (1992). On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well-being. British Journal of Psychology, 83, 133–145. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02429.x.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge terzStiftung for its assistance in recruiting study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baumann, D., Eiroa-Orosa, F.J. Mental Well-Being in Later Life: The Role of Strengths Use, Meaning in Life, and Self-Perceptions of Ageing. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 1, 21–39 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-017-0004-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-017-0004-0