Abstract

This paper applies Emmanuel Levinas’ philosophy to the management practice of leadership. Specifically, it focuses on servant leadership, which is considered the most dyadic other-oriented style. While often viewed altruistically, servant leadership can still be egological if it totalizes followers to a leader’s interests and to organizational ends. This paper conceptualises an enriched version of servant leadership using key ideas taken from Levinas’ understanding of the infinite Other and then describes this style using relevant examples. This novel approach, Servant-Leadership-for-the-Other, offers a theoretical lens by which to enrich existing leadership practices as well as providing a style of leadership better suited for the twenty-first century.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Any introductory textbook lists the five core practices of management as controlling, organizing, planning, staffing, and leading (Schermerhorn et al. 136). The last of these, leading, is the focus of this paper, and specifically, how might the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas be useful in understanding and enhancing the management practice of leadership. Leadership has long been studied in the management sciences and there has been a large body of knowledge collected (Parry and Bryman 121). Leadership research has focused on individual traits (Kirkpatrick and Locke 88), leadership styles and behaviors (Mackenzie and Barnes 108), and the psychology driving individual leaders (Messick and Kramer 114). There is also ample research critical of leadership noting, for example, that it is the heroization of whiteness (Liu and Baker 106), constructed in oppressive ways (Ford 57), romanticized and over-credited (Collinson et al. 40), an alienating social myth (Gemmill and Oakley 64), manipulative of employee inner subjectivity (Bell and Taylor 16), and been overrun with naive positivity (Collinson 39).

This paper uses Emmanuel Levinas’ philosophy to shed light on the egological heart of leading and to offer another alternative. It does this by using Levinas’ concept of the Other to build on what is considered to be the most other-oriented leadership style, that of servant leadership (SL) (Rhodes 128; Sendjaya et al. 139), in order to develop and enriched style called Servant-Leadership-for-the-Other (SLO). In doing so, this paper heeds the call from the SL literature to break the “theoretical lens in which servant leadership has been confined and reshape how we analyze servant leadership” (Eva et al. 53, p. 123). This novel approach, using philosophical theory and methodology (Laurie and Cherry 94), moves leadership away from its essentialist roots toward a more transcendent understanding (Jones 84). Such a refocus can shift management thinking away from its preoccupation with the self (Willmott 159) and toward the Other and a community of Others (Desmond 48), which may alter how leaders act in organizations as they “advocate for a culture based on alterity and a humanism of diversity, which is supported, mediated and practiced through this new managerial ethos” (Bruna and Bazin 29, p. 582). This means, for example, that instead of dealing with behavioral questions associated with efficiency and motivation, leadership becomes more about dealing fairly with inequality, conflict, domination and subordination, and manipulation. To achieve this end, this paper begins with an appraisal of existing leadership styles, and in particular SL, noting that leadership is often egological in nature and needs rethinking.

Is Leadership an Egology?

Leadership is an often-researched topic in the management literature. This is not surprising given its prevalence in human society (Bass and Bass 14). References to leadership are also evident in the philosophical literature, both Western (Cusher and Menaldo 44) and Eastern (Wang et al. 155), and there is widespread belief in this literature that leadership is necessary for effective societal functioning. In addition to this, leadership also plays a key role in fostering organizational well-being, both individually and collectively (Inceoglu et al. 80; van Dierendonck et al. 153). Although easy to find in practice, leadership is hard to define. For this paper, we use Antonakis and Day’s (5) broad description of leadership “as a formal or informal contextually rooted and goal-influencing practice that occurs between a leader and a follower, groups of followers, or institutions” (p. 5). Leadership is inherently about relationships with others and if we use Levinas’ notion of the Other as a lens by which to examine the practice of leadership, then we can evaluate how other-oriented it actually is. Other than this understanding, there is no further attempt to define leadership per se except when evaluating differing styles.

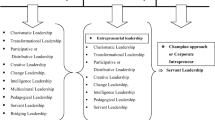

If we think of leadership styles over the last few decades, then broadly speaking, four come to mind: transactional (Burns 31), transformational (Avolio et al. 9), positive (Blanch et al. 20), and relational (Uhl-Bien 150) (see Fig. 1). Within these broad styles, there are, what could be termed, substyles, and examples of these are provided in Fig. 1 below. For parsimony’s sake, not all possible substyles are provided (e.g., democratic leadership (Gastil 63) is not included). It is important to note that while these broader styles (and their substyles) have only roughly developed in a linear manner, there has been a definite progression from more self-oriented leadership (i.e., more egological) styles to less self-oriented over that time. This suggests leadership has become less focussed on the individual per se (i.e., the great leader myth) and more concerned with followers (e.g., positive leadership), the interactions between followers (relational leadership), and how this shift relates to organizational ends.

At any one time, several of these broader leadership styles (and/or their substyles) could be active within an organization and in general, each offers some value (Yukl 161). For instance, transactional leadership incentivises followers to achieve independent goals for both the organization (e.g., profit) and themselves (e.g., remuneration) (Burns 31). Transformational leadership engages follower needs such as being treated fairly, self-esteem, and autonomy using concepts like vision, belonging, and development (Bass 13). Positive leadership takes this further via “a positive moral outlook, positive modelling of the followers’ behavior, and positive social exchanges between the leader and the followers” (Blanch et al. 20, p. 171). And lastly, relational leadership emphasizes networking between individuals in an organization, which reveals “more about where, when, how, and why leadership work is being done than about who is offering visions for others to understand and perform the work in question” (Raelin 127, p. 134).

Despite these benefits, it is not hard to realize why some leadership styles are more egological than others, and why these styles are more prevalent in organizations. The institution of business often reflects an economic paradigm that encourages maximizing self-interest to reach overall good (Aasland 2; Jones 83; Roberts 135). This paradigm “creates a social world in which alterity is discursively erased; in the economic social world, there is only one subject position, and a world of objects on which the subject acts” (Shearer 140, p. 558). Unfortunately, leadership practices can be reflective of this inadequate social world (Ferraro et al. 55; Ghoshal 65). If a leader’s identity is that of an economic actor, who “invests self-interested action with the full weight of moral probity” then they have “no Other whose being might obligate him [or her] to a good that is greater than [their] own personal interests” (Shearer 140, p. 558).

If we evaluate transactional and transformational leadership styles through an egological lens, then both treat followers as means, and not ends (Bowie 23). Both tend to thematize the relationship with followers through a top-down managed approach, which in turn, can make the responsibility to them indirect and inauthentic (Pendola 123). Positive leadership styles are better; they foster elevated levels of performance by promoting altruistic conduct toward followers (Dinha et al. 49; Lemoine et al. 96). However, substyles within this broader category can still be more about master than servant (Hoch et al. 78). For example, authentic leaders are encouraged to be self-exploratory about, and to self-justify, their seniority, and their decisions, within the organization (Bendell and Little 17). Finally, because relational leadership emerges from a process of collaborative meaning-making, it is inherently related to the collective as opposed to an individual (Raelin 127). At first glance, this seems an improvement on earlier understandings of leadership, since it relies on an authentic recognition of the self in the other (Buber 30) and it is through this I-Thou relationship that both parties are transformed. However, in organizations, brimming as they are with politics and power, the I-Thou relationship rarely exists. Certainly, Levinas might agree that leadership is the “medium and outcomes of social relationships” (Knights and O’Leary 90, p. 133) but this is not a shared process, rather the Other breaks into my egocentricity and announces my responsibility to and for them.

While relational styles are certainly more other-oriented, such leadership emerges from the connections within a group and often disperses when no longer needed or when the group itself ceases (Hanna et al. 76; Raelin 126). This differs from dealing with the individual in front of you, a person who calls you to infinite responsibility via their presence. Because SL starts with followers and their presented needs, it is considered the most other-oriented dyadic style of leadership and is closest to the ideas of Emmanuel Levinas (Dion 50; Rhodes 128; Udani and Lorenzo-Molo 149). Consequently, the next section unpacks SL in more depth and considers its other-oriented nature.

Servant Leadership

Rooted in religious traditions of sacrifice, SL begins with the desire to serve others which in turn motivates one to lead. In this way, SL ensures that follower needs are prioritized (Greenleaf 72). The test of SL’s effectiveness, according to Greenleaf, is whether followers develop more fully as human beings, whether they become servants themselves, and whether SL is contributing to the least privileged in society. Interestingly, both Sendjaya et al. (139), and later Eva et al. (53), note that while SL has qualities like other ‘positive’ leadership styles, it is distinctive because it alone tries to prioritize follower's needs above that of the leader, and the organization. Servant leaders (SLs) are “primus inter pares (i.e., first among equals)” (van Dierendonck 152, p. 1231) who act as stewards of followers entrusted to them by the organization. As such, states van Dierendonck, SLs do not act from a position of power to achieve their ends rather, they rely on persuasion and influence. Moreover, they do not equate service with servility nor have low self-esteem. It is not surprising SL is appealing. After all, it connects with the part of “the human psyche that is indestructibly optimistic, the part that longs for the ‘ideal’, the ‘promised land’, ‘heaven’, ‘utopia'; the part of us that is, in essence, incurably 'religious'” (Bradley 25, p. 44).

A review of literature uncovered multiple frameworks characterizing SL (see e.g., McQuade et al. 112; Parris and Peachey 120; Sendjaya et al. 139; van Dierendonck 152). Fortunately, Eva et al. (53) provide a helpful synthesis in which they define the essence of SL as having a particular “motive, mode, and mindset” (p. 114). A SLs motivation is altruism; they have a “belief that leading others means a movement away from self-orientation” (p. 114). A SLs mode cultivates psychological well-being, emotional maturity, and moral wisdom of followers. As stewards, followers entrust themselves to SLs in the hope of elevating their better selves. Certainly, this trust seems well-placed with SL improving outcomes like job satisfaction (Schneider and George 137), creativity (Neubert et al. 119), commitment (Han et al. 74), and well-being (Gotsis and Grimani 69). Lastly, a SLs mindset involves the “outward reorienting of their concern for self toward concern for others within the organization and the larger community” (p. 114). The goal is to enhance the community of which followers are part, such that all flourish. In organizational communities for instance, SL has been shown to enhance trust (Washington et al. 156), citizenship behaviors (Chiniara and Bentein 37); justice (Schwepker Jr 138); team effectiveness (Hu and Liden 79), and collaboration (Garber et al. 61).

Eva et al. (53) also note that SL can be multidimensional with spiritual, ethical, and communal elements. They argue SL is imbued with spiritual values and is similar in concept to spiritual leadership (Fry 58, 59) in that it responds to followers holistically enabling them to integrate their work and private lives. SL is ethical because such leaders employ methods that are morally legitimized and that appeal to transcendent ideals, values, and needs of followers (Graham 70). Finally, SL is communal because its concern is for the wider society, for which it want to create value indirectly through developing followers (Liden et al. 102).

Perhaps because SL is considered other-oriented (van Dierendonck 152), it is often assumed to be ethical. However, it may be what Barthes (12) labels, “Innocent speech… a neutral concept void of ideological connotations that might serve special interests” (cited in Eicher-Catt 52, p. 17). Like other forms of leadership, SL can involve the construction of follower identity and the management of meaning – both of which reduce the Other (followers) to the Same (the leader’s egocentric view of them). As Goffman (67) astutely noted over 60 years ago, “Built right into the social arrangement of an organization, then, is a thoroughly embracing conception of the member – and not merely a conception of [them] qua member, but behind this a conception of [them], qua human being” (p. 164). In other words, most management practices (including leadership) are as much about the construction of ‘appropriate’ individuals as they are about supplying goods and services. Alvesson and Willmott (4), writing 40 years later, concur with Goffman’s analysis. They argue that organizations regulate the identities of employees to bring about self-understandings and alignment of work congruent with their purposes, and that this occurs through “the manufacture of subjectivity… the focus is on the employee’s ‘insides’ – their self-image, their feelings, and identifications” (p. 622), as opposed to objective forms of control.

Applying this idea to SL has it employing a specific language of sacrifice (i.e., I will put you first; I will do what is best for you; I am concerned with your needs) that invites followers to view themselves as dependent on the leader for their well-being. Instead of empowerment, followers can struggle to “make decisions and act in the absence of their leader” (Liu 105, p, 1106). By expressing the values connected with SL, the leader also generates agreement about what a servant is, which in turn, encourages others to identify with the leader’s value system at the expense of their own. Moreover, because SL produces this sense of belonging, “being a member of the wider corporate family may then become a significant source of one’s self-understanding, self-monitoring and presentation to others” (Alvesson and Willmott 4, p. 630). Finally, if the culture of an organization is servant-oriented, then both leader and employee identity may be re-interpreted. For instance, if behaving like a servant leads to improved organizational performance, then leaders are invited to become sacrificial to ensure organizational success, and employees are invited to accept this sacrifice to “become enterprising persons” (p. 632).

The discourse and actions of SL shape the organizational environment in such a way that employees use the meaning of these for their behaviors and contextual interpretation (Calas and Smircich 33). However, as Collinson (39) notes, this environment is not politically neutral and ideas like altruism, sacrifice, and care do not simply exist but come loaded with organizational values and norms that can conflict with employees’ real needs. Consequently, SL can be a form of what Foucault calls ‘pastoral power’ (Bell and Taylor 16), which is concerned “with cultivating the welfare of an entire population of citizens” as well as looking “after each individual in particular, through his or her entire life” (p. 340). From this perspective, SL hinges “around relations of power conjured up in the idea of the manager shepherding the flock” (Simpson et al. 141, p. 355). For instance, when SLs exercise compassion toward followers, they may be practicing a form of individualized pastoral power whereby they hope to ‘save’ the individual by getting to know their innermost thoughts and concerns. Even though this personal care appears other-oriented, it is often exercised in a benevolent paternalistic manner (Nadesan 117). Moreover, if such care is performed to enhance follower well-being, and therefore commercial success, then SLs may also be using totalizing pastoral power. Both ‘spiritual’ forms ensure caring for the other becomes a mode of power that controls employees “through disciplinary technologies that focus on the scientific governing of the soul using primarily psychological techniques” (Bell and Taylor 16, p. 345).

Despite focusing on others, SL still achieves this through a process “that starts with a category and ends with a judgment relative to that category… through this move the ‘Otherness’ of the Other, the exceptional, is neatly bracketed and covered over” (Introna 81, pp. 212–213). In other words, SL starts by serving followers (i.e., the category) but it is the leader’s idea of service (i.e., their judgment compared to the category) that is enacted. In doing this, SLs can assimilate the individuality of their followers into their cognitive framework (i.e., the Other is bracketed and covered over). A SL does this because they have “moral authority… They follow truth. They follow natural law. They follow principles” (cited in Collinson et al. 40, p. 1633). However, this is a limited ethics of the Other, in that it is “a sense of immanence and the closing down of the potential for critique through appeal to a universal and transcendent truth” which ultimately “reduces ethics to a timeless, yet mystical sense of purpose possessed by certain privileged leaders” (p. 1633). This, as Eicher-Catt’s (52) analysis suggests, may be a result of SL’s overriding masculine connotations stemming from its religious, patriarchal roots.

Genuine other-oriented leadership does not start by serving followers who reciprocate positively, either in terms of personal well-being or organizational outcomes. Nor does it begin from a horizontal dialog between agents. Such interactions are laden with power and politics and can result in the assimilation of the other’s identity into leader-centric worldviews, and ultimately, the organization’s wider economic agenda (Aasland 3; Bevan and Corvellec 19; Roberts 135). Therefore, given the limitations of such leadership, what might a legitimate SL towards, and for, the Other look like? To achieve this, the following sections unpack the notion of the Other and explain Levinas’ unique perspective of this phenomenon. This exposition is followed by an application of Levinas’ insights to describe Servant-Leadership-for-the-Other (SLO), which is neither dyadic nor relational in the way other approaches are.

The Idea of the Other

The idea of the Other has challenged philosophical thinking for a long time. In its plainest form, this epistemological challenge asks, “how can I know that Others exist?” If the Self is the only thing that can be known and verified (Avramides 10), then any philosophical method trying to answer this question, sourced as it is in the Self, is solipsistic. This becomes problematic since it collapses the notion of the Other into one’s cognitive hierarchy, whereby the Other’s individuality and social context, along with their innate value is compromised (Blok 21). Indeed, Emmanuel Levinas (98) in his magnum opus Totality and Infinity (TI), makes this argument when he states that the way we conceive others “has most often been an ontology: a reduction of the Other to the Same by interposition of a middle and neutral term that ensures the comprehension of being” (p. 43). This is Levinas’ way of saying that we often categorize others to ensure they appear the same – for example, as employees, investors, or stakeholders. This perspective is also within us, “The relation with the other is here accomplished only through a third term which I find in myself. The ideal of Socratic truth thus rests on the essential self-sufficiency of the same, its identification in ipseity, its egoism” (Levinas, p. 44), thereby ensuring we tend to see the other person as we see ourselves (Blok 21).

The idea of ‘the Other” in philosophical history offers support for Levinas’ claim. For instance, ‘the Other’ in Plato’s dialogues are Socrates’ interlocutors whose ideas become subsumed into Plato’s worldview via the dialectical method. As Chen (36) notes, this deceptive form of dialogue appears to receive the Other but only for the veiled purpose of bringing them closer to oneself and one’s perspective. Such solipsism “has encouraged monstrosities like the Cartesian cogito, the Spinozan conatus, the Leibnizian monad, the Fichtean ego, and the Nietzschean ūbermensch.” The problem, Levinas (98) might argue, is that such thinking suppresses pluralism and ensures conflict is a “permanent possibility” (p. 21). Totalizing the Other, (i.e., assimilating them to my worldview, my values, and my beliefs), ensures conflict “is an ontological event, the production of pure experience of pure being” (p. 21). For Levinas, the holocaust was an extreme expression of this will to being; this desire to ‘totalize’ the world within the self’s conceivable knowledge (Aasland 3).

Various continental philosophers have addressed the problem of the Other, not by analogizing it with the Self (see e.g., John Stuart Mill), but by starting with “Kant’s notion of a priori (i.e., before we experience the world) category of ways of thinking” (Benson 18), from which they argue ‘the Other’ is an a priori category necessary for humans to be able to experience the world. Taking this idea and building on the work of Husserl, who observed that “the presence of the Other is always pervaded by a dimension of inaccessibility, an absence, that accentuates, for the perceiving consciousness, its own limits, thus challenging its egocentric structure” (Kenaan 86, p. 486), Levinas argues that “the Other, qua Other, is revealed in ways that are intended to challenge any positive description and thus render the phenomenal surface that meets the eye as essentially insufficient” (p. 486). The next section develops how Levinas understands this challenging encounter with the Other.

Levinas and the Infinite Other

During an interview with Philippe Nemo in 1982, Emmanuel Levinas summed up his philosophy of the Other using the phrase, ‘after you, sir’ (Rhodes 131). This simple expression captures the spirit of how Levinas viewed other people, that they come before the self. Levinas, like Immanuel Kant, believed morality is universal, absolute, and a priori. Unlike Kant, Levinas rejected the idea that how we relate to others comes from our reason; rather, it comes from something outside the ‘I’ (the solipsistic ego), namely via the Other. Therefore, how we treat people “can only be awakened and manifested as a response to the call for responsibility from the Other” (p. 64). For Levinas, philosophical thinking about the Other “is not the love of wisdom, but the wisdom of love – it is primarily ethical not ontological” (Large 93, p. 25). Alluding to Plato’s famous phrase in the Republic, that the good lies beyond being, Levinas (98) argues for an ethics (i.e., the relationship to the Other) that is beyond ontology. This is not an ethical theory per se but rather what Derrida (47) labelled an “ethics of ethics” (p. 78), an attempt to define the essence of the ethical relationship. So, how does Levinas come to this conclusion?

Levinas (98) begins with Descartes’ ontological argument for the Infinite in his Third Meditation, that “we could conceivably have accounted for all ideas, other than that of infinity, by ourselves” (p. 49), which implies human beings have an idea of infinity; an idea there is something that transcends human understanding, something that resists our natural tendency to solipsism (or what Levinas refers to as ‘the Same’). For Descartes, this Infinite is God but for Levinas, it is l’Autrui (the Other). We relate to and engage with the Other in our daily lives but there is something about them that is beyond our knowledge. They have an inherent mystery that we can never fully apprehend; they are always exterior to us (Lim 103).

Understanding this encounter with the Other implies I am not isolated; other people confront me, and I experience them. These others states Levinas (99) “is what I am myself is not. The Other is this, not because of the Other’s character, or physiognomy, or psychology, but because of the Other’s very alterity” (p. 83). The Other is not my antithesis or my alter ego rather, the Other ruptures the world I have made for myself. Consequently, the Other conditions my subjectivity because they are beyond me. Without the Other, I would not be an individual; I would be part of a totality, bereft of my uniqueness (Davis 46). Moreover, according to Levinas, the self does not exist before the Other enters the picture. The self emerges in response to the call of the Other; it is an outcome of the interaction that starts with the Other addressing the I (Morgan 116). Levinas refers to this as the “posteriority of the anterior” (Levinas 98, p. 54), which he explains as when the “After or the Effect conditions the Before or the Cause: the Before appears and is only welcomed” (p. 54, original italics). Therefore, the notion of infinity [or the transcendent Other] comes via our social relationships and “the way in which the Other presents himself [or herself], exceeding the idea of the other in me” (Levinas 98, pp. 50, original italics). For Levinas, meeting the Other “is the most basic subject for philosophical reflection because nothing precedes it or has priority over it” (Davis 46, p. 48).

The existence of the Other requires a response from me. As Levinas (98) observed, humans have a consciousness and they use this to conceive the world around them. When they do this, they understand the world as a totality, a systematic orderly whole. Morgan (116) calls this “a kind of idealism, a taming of the world and domesticating it to my capacities and venue as if my capacities were wholly general and detached and impersonal”. In doing this, “I make everything thinkable and knowable by drawing everything within the border of [my] conceptual capacities’ (p. 39). In other words, we create and want the world for ourselves; our thinking and the objects of our thinking, whether things or people, we reduce to our desires (i.e., the Same). However, the Other’s existence calls “into question my spontaneity” (Levinas 98, p. 43). They challenge my self-absorption and isolation, they say no to my unchecked desire, and no to unbridled self-interest.

Levinas (98) describes this encounter as “the way in which the Other presents himself, exceeding the idea of the Other in me, we here name face” (p. 50, original italics). However, this is not simply “an experience in the sensible sense of the term, relative and egoist” (Levinas, p. 193), which would be totalizing. Instead, as Davis (46) explains, “the Other is simply there, present to me in an originary and irreducible relation that Levinas calls le face á face (the face-to-face)” (p. 46, original italics). However, because the face of the Other challenges my freedom and my power, I may, initially at least, want to harm them: “I can wish to kill only an existent which is absolutely independent, which exceeds my powers infinitely, and therefore does not oppose them but paralyzes the very power of power. The Other is the sole being I can wish to kill” (Levinas 98, p. 198). Indeed, the face’s “primordial expression, is the first word: ‘you shall not commit murder” (p. 199, original italics). Consequently, when we come face-to-face with the Other, we have a choice – we can either respond with violence or with responsibility. Because the face of the Other is before me, I cannot choose not to respond, I cannot escape their appeal. Instead, I can use my freedom to either totalize them, which for Levinas is violence toward the Other, or to be unconditionally open, vulnerable, and compassionate, regardless of how different they are, and in doing so become fully human.

If TI is about the infiniteness of, and responsibility for, the Other, then Levinas’ (100) later work, Otherwise than Being (OB) turns “back to the moral sensibility of the subject awakened by the other, to its unique temporal and moral de-phasing, a fissured self, traumatized, held hostage by the other” (Cohen 38, p. xii). The attention now is on the repercussions of this asymmetrical relationship on the I who must ethically subject themselves to and for the Other. Moreover, as Critchley (43) observes, whereas TI finds “the point of exteriority in the face of the other” (p. 17), in OB, in an attempt to avoid the trap of ontological language (Derrida 47), Levinas puts more emphasis on discourse as exteriority’s primary source, and in particular the difference concerning the Said (le Dit) and the Saying (le Dire).

For Levinas (100), philosophy has been concerned primarily with the Said (e.g., philosophical propositions about the world). Unfortunately, prioritizing the Said (i.e., the ontological) has come at the expense of the Saying (i.e., the ethical), which is the “underlying situation, structure or event in which I am exposed to the Other as a speaker and receiver of discourse” (Davis 46, p. 75). The Saying, argues Levinas (1998b), is pre-original because without it there would be no conditions for language (i.e., for the Said). By focusing only on the Said “we overlook the essential exposure to the Other without which there would be no utterance nor meaning” (Davis 46, p. 75). In this way, discourse (or ‘the saying’) is not about expression alone but also conditions consciousness. While both the Said and the Saying are required for making sense of the world, the Saying ensures that “the ‘I’ does not meet the Other as an intact subject facing another subject rather, it “exposes the ‘I’ to the alterity of the Other… [and] belongs to the order of the traumatic, to a vulnerability or openness to the Other” (Iyer 82, p. 40). Before I even exist as an individuated subject, I have responsibility for the Other, entirely and without contest, because “my existence is completely bound up with my relation to him or her” (Davis 46, p. 80). That is why Levinas describes this relationship with the Other as “an obsession, a shuddering of the human quite different from cognition”, “the wound that cannot heal over”, and as emptying “like in a hemophiliac’s hemorrhage” (Levinas 100, pp. 87, 126).

Since Levinas (98) resists categorizing the Other, how does he deal with wider society when it comes to ethics? He does this through the idea of le tiers (the third party or the other Others). My face-to-face encounter with the Other suggests the possibility of an entire world beyond the self: “The third party looks at me in the eyes of the Other – language is justice… the epiphany of the face qua face opens humanity” (p. 213). Taking this idea further in OB, Levinas (100) writes le tiers are present in the proximity of the Other because the Other is never just my Other. Therefore, justice is more than applying abstract frameworks, it involves a society of others where everyone cares for everyone else: “Justice, society, the State and its institutions, exchanges, and work are comprehensible out of proximity. This means that nothing is outside of the control of the responsibility of the one for the Other” (Levinas 100, p. 159). It is imperative to grasp, however, that this obligation does not replace the primary and originary ethical relation with the Other because it is only through this asymmetrical relationship that le tiers can be fully recognized (Davis 46).

Levinas avoids the classic philosophical problem of whether others exist. The self, for Levinas, does not pre-exist before its encounter with the Other; rather, it forms as it meets and engages with the Other. Moreover, Levinas avoids epistemological questions by focusing on ethics (or the relationship with the Other) which is a priori over everything else. Interestingly, Critchely (42) summarizes Levinas’ philosophy as a critique of our ego which wants to reduce everything to its understanding, while asking us to think about our infinite accountability to the Other. If that is the case, then what can such critique offer to leadership? How might Levinas’ understanding of the Other enrich SL as a management practice?

Servant-Leadership-for-the-Other

SL is usually considered the least self-oriented and most caring form of dyadic leadership (Rhodes 128) but it has limitations. While it is a positive leadership style that often benefits followers, the organization, and the wider community (Langhof and Güldenberg 92; Lee et al. 95), it could be enriched further. Relational leadership does offer a means of overcoming SL’s limitations, but this style is limited in its ability to constitute leader ethical subjectivity (Steiner 143). Given these issues, this paper offers a version of SL that is more other-oriented, which reverses the dyadic relation between leader and follower, which fosters wide collaboration through the third party, and which encourages development of a leader’s full ethical self. If we start with the framework that Eva et al. (53) developed to synthesize SL (i.e., motive, mode, and mindset), as well as the different dimensions of SL (Spiritual, Ethical & Communal), and we augment that using Levinas’ ideas about the Other (see also Jones 84), then we can produce an understanding of what SLO might look like in practice (see Table 1 below).

Before going any further, it is important to stress how difficult it is to engage with business organizations in a Levinasian way, and that promoting SLO, does not downplay this difficulty. Indeed, several authors have noted the challenge of applying Levinas in this context (Jones 83; Mansell 109; Roberts 135), arguing business’ raison d’etre is “serving its self-interest with profit as a proxy” (Bevan and Corvellec 19, p. 210), and that it is an institution where leadership is often reflective of this underlying motivation (Rhodes 128; Shearer 140). Unfortunately, as Ketcham et al. (2016) observes, “Levinas himself left us no roadmap or ‘recipe’ for understanding just what responsibility to the Other means” (p. 38).

Consequently, this paper does not offer SLO as a comprehensive replacement for SL, which would simply be another form of totalizing egological leadership. Rather, SLO is a “responsible response developed in the interfacial meeting” when SLs are drawn from themselves “to a metaphysical space where the opportunity to become (not just be) is possible.” (Kertcham et al. 87, p. 39). And it is here, in this durable ethical space, that SLs have a chance to truly “exercise the copper rule […]: do unto others as they would want done to them” (p. 39). In other words, SLO is not an overarching style but instead is the individual concern of an agent (i.e., a leader) for a follower (i.e., for otherness) in a specific and unique context (i.e., at that time and place in an organization), whereby such concern works to delimit alterity (i.e., embrace follower uniqueness and difference) while unfolding the practical implications of this (Bevan and Corvellec 19). Indeed, it is with such practicality in mind that the sections below hope to unpack ideas where Levinas’ philosophy could enrich SL based on the criteria provided in Table 1.

Motive

For SL, the motive is serving others (Eva et al. 53) but unfortunately, the economic egology found at the heart of organizations often ensures this service is as much for the leader and the firm, as it is for the employee (Shearer 140). Moreover, given its religious undertone, SL can become an instrument in the organization’s tool belt “to re-engineer the thought processes of employees and to heighten devotion to the corporate ideal, by imbuing routine organizational processes with a heightened sense of the mystical” (Tourish and Pinnington 148, p. 165). If, however, a leader’s motivation was before the self and its freedom and did “not rest on any authoritative structure” (Caygill 35, p. 149), then such service might be stripped of its sovereignty (Levinas 100), that is, it might be service motivated by responsibility for the Other and their autonomy. This is still a spiritual response because it accents the transcendent Infinite which becomes “the moral force encountered in the Other’s face as the subject’s obligation to and responsibility for that other person” (Cohen 1994 cited in Morgan 116, p. 144).

Unfortunately, there are mechanisms at work that insulate leaders from followers. Organizational structures often invest leaders with hierarchical power, and this can be difficult to give up even if the leader wishes to do so (Blok 21). Systems like finance can reduce employees to impersonal criteria such as numbers on a balance sheet or key performance indicators (Lewis and Farnsworth 101), while human resource systems can reduce them to roles (Rhodes and Harvey 133) or consumers of benefits and development opportunities (Dale 45). These mechanisms often erase any possibility of “genuine ethics since the unstable moment of recognition of the Other is translated into an abstracted form” (p. 186). At the same time, leaders can develop a preoccupation with themselves and how they appear to the powers above them (Roberts 135). Such narcissistic thinking means leaders become independent of followers, which cuts them off from the fundamental premise of Levinas’ ethical worldview, openness to the Other.

SLO, on the other hand, strives to consider the humanity of everyone in an interaction. Followers are not simply resources, and they are more than roles or key performance indicators; indeed, they are neighbors and part of a social reality necessary for business ethics to exist (Jones 84). To reduce moral distance, SLO fosters proximity with followers (Mansell 109), not for control or proficiency, but to understand and respect their differences and individuality. Not surprisingly, enhancing nearness has been shown to reduce intergroup fear and stereotypes (Pettigrew and Tropp 124; Stephan and Stephan 144). Perhaps leaders can justify, on economic grounds, the use of financial mechanisms to achieve shareholder returns but in doing so, they often reduce employees to an economic category, and this may be violence (Lewis and Farnsworth 101). As a cure for such reductionism, SLO desires continual negotiation with those affected by their decisions, as well as applying any other processes flexibly to consider follower individuality while reflecting on how applicable these processes are in each unique situation (Mansell 109).

SLO, endeavours where possible, to disrupt systems that manage subjectivity (Alvesson and Willmott 4). Such leaders are resistant toward any process “that intervenes in an employee’s life in order to get employees to sacrifice more of themselves to the needs of the organization” (Greenwood 73, p. 264). To accomplish this, SLO is “practiced through questioning and problematizing the morality vested in organizational practices” (Rhodes 129, p. 1504), and in doing so, it contests the sovereignty of the organization and its view of the world (see e.g., Bakan 11). A good illustration of SLO comes from Fairhurst et al’s. (54) analysis of downsizing at a manufacturing firm. After rounds of painful restructuring, the manager consulted employees and developed an alternative system based around employee dignity and respect even though this drew the anger of senior management whose focus was on efficiency and costs. This action led to the firm’s written protocols changing so that employee interests would be primary in any future downsizings. This differs from a standard SL approach, for instance, which might help employees cope with downsizing out of a sense of compassion but fail to challenge the actual restructuring process, and its underlying reasons, since this action fulfils the organization’s, and the management’s, wider interests (Gotsis and Grimani 69).

Instead of managing their subjectivity, SLO approaches employees with an a priori hospitality that allows them to decide what is best for themselves. This means communication is dialogical – it should not favor the dominant position of organizational privilege (Maak and Pless 107) but instead, should support the radical disruption of the leader that is central to genuinely loving others. To do this, SLO listens for employee’s “radical alterity” and “makes a place for it” which means it “listens for and makes space for the difficult, the different, the radically strange” (Lipari 104, p. 138). For example, when constructing human resource policies about compensation systems, SLO elicits open-ended employee input, or more radical still, lets employees set their own goals and pay levels. SEMCO, the Brazilian conglomerate, has had success with this approach. In part, this was also because SEMCO made all financial information open to employees and because employees had developed a personal stake where nobody wanted to take advantage of the process (Vanderburg 154).

SLO is the critical conscience of the organization. It is not the referee of fairness and justice, using moral codes and bureaucratic policies that can suppress the Other. Rationalist approaches tend to imbue leadership decisions with an element of bias, which often favors the organization (Aasland 1). Such thinking totalizes others by ignoring or surpassing their multiple voices (Rhodes 128), while also ‘liberating’ leaders from their responsibility (Jones 83). If anything, SLO desires to release the plurality of voices, not constrain them within pre-existing abstract categories (Gama et al. 60). Certainly, this is challenging in an egological system that suppresses the possibility of such outcomes (Bauman 15), and therefore, the motivation of SLO more than anything else should be to establish organizational goals and capabilities that privilege the transcendent nature and alterity of the Other.

Mode

Eva et al. (53) describe the mode of SL as “one-on-one prioritizing of follower individual needs, interests, and goals above those of the leader” (p. 114). This comes from taking an interest in followers’ personal lives and their specific behaviors, blurring the line between private and work. Moreover, SL seeks to cultivate entrusted followers “in multiple areas such as psychological well-being, emotional maturity, and ethical wisdom” (p. 114). Altogether then, SL strives to develop well-rounded moral employees who care about the organization and who want to see their wider community flourish.

While valuable in principle, SLO understands that trying to cultivate follower morality is fraught with egocentric bias (Roberts 135) and can reflect an ideology “that configures all aspects of existence in economic terms” (Brown 26, p. 17). Moreover, SLO rejects any ethic of reciprocity entrenched in the idea that relationships are about human flourishing and cultivating social integrity (Rhodes and Badham 132). For Levinas (98), leader and follower relationships are “irreducible to objective knowledge” (p. 68) and as such, are both non-reciprocal and conditional in that the leader develops their own moral identity and obligations as they “arrive in the context of their relationships and the social structures in which those relationships exist” (Rhodes and Badham 132, p. 78). Instead of privileging their leadership, followers help the leader comprehend that “there is a sense of goodness and a realization that there is more at stake in my life than myself and my fulfilment” (Arnett 7, p. 58).

Importantly, SLO does not take on the moral identity of followers, which would be totalizing in reverse. Nor does it mean SLO is simply a social construction created by followers (Meindl et al. 113), rather it is an understanding that “ethics as responsibility for the Other is an act that makes possible [my] human life – without the Other, there is no I” (Arnett 7, p. 57). For SLO, this means at least two things. First, who leaders are in the organization is not a product of their position or authority so much as it is of their responsibility for other people, which is inexhaustible and without reciprocity. Therefore, all behavior and decision-making must come from an attitude that is fundamentally based on openness, service, and compassion for others (Steiner 143). Second, SLO constantly questions leader identity in relation to the followers for whom they are responsible. Theirs is a constant reflection on how they deal with the particularity of every individual and situation and the ethical freedom that comes from putting followers first (Rhodes 128).

Levinas (98) asks us to consider the uniqueness of each person, to be “my brother’s [and sister’s] keeper” (Gen. 4:9). This means being open and vulnerable to the strangeness of others and doing this “independent then of belonging to a system, irreducible to a totality” (Levinas 97, p. 165). To develop an organization that reflects this openness, SLO embraces “diverse cultures and subjectivities as claimants to mutual recognition” (Hancock 75, p. 1370) as well as recognizing that individuals “are always in process, as it were, but that such processes of becoming require a level of recognition that not only tolerates but rather embraces difference as an integral ontological precondition” (p. 1371). This approach lessens managing differences between people, as well as in-group and out-group categories, and focuses on respecting others regardless of distinction. In the case of minorities for instance, instead of categorized as different, SLO respects such people, and indeed rewards them, for overcoming the challenges of work that most people do not face but also for how they are altering society’s views about minorities. Such people teach leaders about what it is to walk in the shoes of the marginalized in society and what this means for organizations to meet their real needs.

Serving, for Levinas, is more than going “beyond self-interest”, “being first among equals”, or “being a steward who holds the organization in trust” (van Dierendonck 152, p. 1231); rather it involves suppressing desires, and paying attention to other’s needs without expectation of reciprocity. To achieve this, SLO goes beyond utilitarian notions that emphasize outcomes “in terms of averaged costs and benefits and imagine [themselves] instead, at the fullest of [their] emotions, in the skin of the worst-off individual in the worst situation” (Bevan and Corvellec 19, p. 215) for whom they are responsible despite themselves. While not a business leader per se, Mother Teresa personifies this approach to service. Selflessly, she devoted herself to aiding the poorest of the poor. Instead of lording over who she served, she adapted her lifestyle to their living conditions and shared in their suffering. This was not just about helping the community; it was also about her own spiritual and ethical development. According to Pio and McGhee (125), in the context of modern leadership, such actions translate as leaders going back to the basics to try and understand the lived experience of all their employees and then create policies and actions which focus on their well-being.

For Levinas (1998a), compassion “can be affirmed as the very nexus of human subjectivity, to the point of being raised to the level of a supreme ethical principle” (p. 81). When experiencing the suffering of others, I feel the call to take on that suffering and to relieve it. Even though Levinas (1998b) views compassion as sacrificial, it is not compassion itself that is ethical, but the opening to others and the sacrificing of my own needs for them. Compassion, he writes, “is not a gift of the heart, but of the bread from one's mouth, of one's own mouthful of bread, it is the openness, not only of one's pocketbook, but of the doors of one's home, ‘a sharing of your bread with the famished’, a ‘welcoming of the wretched into your house’ (Isaiah 58)” (Levinas 100, p. 74).

An example of this is found in Dutton et al. (51) who describes a CEO who had lost seven employees in the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Shortly after the attacks he gathered his staff together and read out the names of those who died. He then arranged for grief counsellors to be available that day and paid for a plane to bring relatives of the victims from Canada and Europe to the USA where he greeted them upon their midnight arrival at the airport. This leader opened himself to the suffering of those families and acted compassionately to relieve their pain at significant cost. Not once did he think about his needs in this demanding situation.

If we take another example, and we apply these ideas of openness, service, and compassion to something like a stakeholder negotiation, several things vary from a typical approach (Blok 22). For example, in 2016 in Auckland, New Zealand, a major building company legally purchased land (Ihumātao) for $19 million that had been confiscated unlawfully by the Government from Māori (the indigenous race of New Zealand) in the nineteenth century. This area was among the first places to be settled by Māori in Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), and now it was going to be used to build 480 houses in a city desperate for new houses (Fernandes 56). Some members of the local iwi (tribe) did not want the Whenua (land), which they whakapapa (their history/ancestry) back to, sold for housing and they organized an occupation. The company took a business approach to negotiations, refusing to return the land, or make significant concessions. In the end, the Government bought the land from the company for just under $30 million in 2020. By that time, the occupation of Ihumātao had lasted four years.

If the CEO of the company had looked to genuinely serve the Other, then the relationship would have begun based on the needs of iwi members, not on what the company wanted. Second, the iwi members would not be a category of people reduced to a historic problem that has no place in the modern world. The CEO would have been open to their suffering while realizing he could not fully understand their position. This separation would have ensured the relationship between the CEO and iwi members was “intrinsically ethical, that is, responsive to stakeholder demands and needs” (Blok 22, p. 248). This insight would require the CEO to substitute in place of the current iwi members who bore or stood for the negative outcomes of historic harms. Rather than applying universal norms to justify the purchase, the CEO’s moral imagination (Werhane 158) might have called for ethical action, dependent on the context in which the issue arose, meaning the land may have been returned despite the loss to the company. After this, the company could have sought redress from the Government who originated this problem with their illegal appropriation of the land in the first place.

Applying Levinas in the case above ensures the SLO dimension is ethical and while iwi members are the focus, it is the CEO’s humanity that develops. Moreover, responding this way is better than using abstract frameworks when it comes to making complex decisions because it deals with proximate social relations. Overall, such leadership is call for a re-imagining of the purpose of business and a re-developing of it in a way that serves the Other first and contributes to a more flourishing society (Tajalli and Segal 146).

Mindset

SL desires a just and fair society. Indeed, such leaders expect “to generate added value for local communities through placing the common good over her/his narrow self-interest…. servant leaders are expected to adopt equitable practices in view of furthering social welfare, thus meeting the expectations of socially disadvantaged groups to a greater extent than other, more conventional types of leaders” (Gotsis and Grimani 69, p. 1002). While SL's intention to further justice is valuable, it is often enacted within a techno-rational context where “justice is a means rather than an end” and where leaders strive “to “ensure that their followers do not feel they are being treated unfairly so that the leader can better achieve his or her organizational goals” (Rhodes 128, p. 1315).

Conversely, Levinas’ view of justice is based on the alterity of others. This is a difficult justice because it supplants “rational reciprocation and exchange with pre-rational affective relationships between people as the very basis of ethically informed justice” and because it comes in a form where the “demands of all of the others cannot be met” (Rhodes 128, p. 1312). It is not a justice that emphasizes reciprocity, serves the common good, or fights for human rights which can be a form “of subjective colonialism, where all the other’s desires are reduced to the desires of the home country, the self” (Nealon 118, p. 32). Rather, it is a justice that extends to a more humane understanding by putting the Other infinitely first.

The complexity in modern organizations means SLs may find it challenging to promote communal justice by adopting an altruistic position toward individuals (Rhodes 128). While SLs may certainly show compassion toward a person, what happens when this conflicts with the ethical demands of another individual (le Tiers or the Third)? As Rhodes notes, “this is the conundrum of an ethically informed justice – it is a pre-rational desire for the other that instigates justice, but justice itself calls for a certain practical rationality that works out how to divide things between all of the others” (p. 1322). For SLO, this means constantly questioning relationships with others for whom they are responsible. Their leadership is not about showing fairness to enhance followers’ well-being and improve organizational effectiveness. Instead, for Rhodes, “it is about navigating the ethical quandaries and dilemmas that leading other people and being responsible for them, inevitably raise” (p. 1322). As Rhodes notes, this type of justice does not revert to abstract norms or principles to make decisions, it “attests to the radical particularity of each such situation and the call to attend to the ethical specificities that this engenders” (p. 1323).

If we take a social justice issue like diversity, then improving this benefits both organizations (Roberson 134) and society (Goodman 68), and it has been claimed that SLs can play a key role in shaping these outcomes. For instance, Gotsis and Grimani (69) argue that “Servant leaders’ attributes are invested with a potential of prompting practices that foster perceptions of inclusion among social identity groups. Servant leaders will encourage fair and socially responsible practices, as well as interventions that reduce tensions between sub-groups, which are in turn expected to nurture followers’ feelings of belongingness” (p. 997). However, as Liu (105) notes, leaders and followers co-construct the practice of SL, which not only means both parties must be open to the notion, but it also encourages the categorization of individuals. In Liu’s intersectional study, employees embraced their senior manager as ‘servant’ but not as ‘leader,’ and there was no evidence of improved trust or inclusion in the organization due to the manager’s SL approach. Moreover, Liu found socio-political systems such as power, gender, and race negatively influenced the effectiveness of SL to improve inclusiveness, which again highlights the issue of conceptualizing such leadership as politically neutral and as a simple altruistic relationship between leader and follower.

Because of responsibility to the Other and the Third, SLO will “seek to deliberate using fair criteria to judge equitably, always under the light and the control of responsible actors” (Bruna and Bazin 29, p. 9). This means adopting the ethics of the Other at the level of the individual, the fairness of the Third at the community level, and at a more global level, the pursuit of “acting in favor of human dignity recognition, individual emancipation, and collective well-being” (p. 9). Applying these three levels to the issue like diversity means SLO, at the individual level, avoids grouping people (Liu 105) while being open to difference in a way that, “The invoked is not what I comprehend: He is not under a category” (Levinas 98, pp. 69, original italics). Certainly, this is challenging in a context that views diversity management through the lens of business success (Konrad 91). However, Rhodes (130) in recognizing this problem, suggests leaders create pockets of resistance “where the ‘business case’ rhetoric of ‘workplace diversity’ can act as a Trojan horse: on the outside are the HRM [business case] arguments, on the inside is a passion for justice and, for the marginalized, a drive for empowerment” (p. 541). For instance, they might establish employee groups “to facilitate experiences that foster the success of their membership and facilitate broader organizational change in respect to diversity” (Green 71, p. 635). Such “groups have been found to participate in advocacy, mentoring, community engagement, increasing visibility, and voice, recruitment and retention, as well as learning and development” (p. 635).

At the community level, accounting for the third must also take place. SLO strives for “mechanisms for judging generosity and threat, for protecting people generally from those that threaten violence in various ways and for organizing life to help and protect all” (Morgan 115, p. 23). This means encouraging vulnerability to and respect for existing diverse community values, norms, and traditions. These SLs emphasize the community’s lived experience, thereby making leadership an act of responsibility toward specific individuals rather than predetermined categories (Pendola 123). If, for example, an organization engages in a project with significant environmental consequences, then SLO would elicit unlimited stakeholder participation from the wider community in evaluating the project. If we take another example from New Zealand, then the principles of partnership, participation, and protection founded in the Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) are community norms and traditions that deserve respect. As such, any SL engaged in such a project would consult widely with the local Iwi before any commitment. Moreover, they would protect Māori Tikanga (culture norms), and ensure Māori are the main beneficiaries. This style of “decision-making helps orient policies for the Third from within the ethics of the Other” (Pendola 123, p. 1536) to engage with diversity at a community level.

Finally, SLO is concerned with diversity at a global level. The demands of the Third via the Other also represent society in general, “The extraordinary commitment of the Other with regard to the third party calls for control, to the search for justice, to society and the State, to comparison and possession, and to commerce and philosophy, and, outside of anarchy, to the search for principle” (Levinas 100, p. 161). This idea goes beyond human rights, which can be totalizing. For Levinas, human rights do not originate within a person, they take shape via one’s experience of the Other. For instance, it is not my right to freedom that matters, it is my freedom that comes from a relationship with the Other (Stone 145) that counts. When applied to something like diversity, it is about the Other’s (and the Third’s) rights, and how they produce an ethical response from leaders. Therefore, at a global level, SLO advocates for laws “designed to mediate and effectuate people’s responsibilities for multiple [diverse] others” (Stone 145, p. 110). SLO desires relationships that lessen the sources of discrimination and engages in diplomacy via face-to-face discourse. These interventions are not about securing business’ economic interests, as they have so often been historically (Klein 89), but are effected for the Other alone.

The mindset of SLs for the other is toward communal justice but not through any abstract principles or norms, and not to serve the organization. Instead, it comes from the primordial ethical relation in which SLs acknowledge responsibility for followers, and through them, others in the organization and the wider community. This collaborative recognition calls SLs to engage with followers while also developing principles of justice that help decide between competing responsibilities of other parties. It is the incessant wrestling with these conflicting interests that conditions, through their accountability to the Other, a leader’s moral and social self.

Levinasian Implications for the Management Practice of Leadership

Broadly speaking, what Levinas’ philosophy means for the management practice of leadership is that fundamentally a leader’s responsibility towards the Other-at-work is theirs alone. Leaders have a personal responsibility to their employees that is non-transferable and non-transitive (Bruna and Bazin 29). This responsibility cannot pass to an abstract institution either. It cannot be “imposed through administrative procedures or organizational policies…it eschews boundaries and barriers” (p. 581–582). This responsibility is infinitely demanding and always starts with and for the individual employee. Such a perspective runs counter to functionalist approaches that reduces leadership to the practice of planning, organizing, commanding, coordinating, and controlling of employees (Willmott 159). It also rejects any economic ideology (e.g., neo-liberalism), and its philosophical foundations (e.g., ethical egoism, social contractarianism), and any theory (e.g., agency theory, transaction cost theory, resource-based theory, and game theory), which views managers and employees as Homo Economicus or rational self-interested maximizers (Ghoshal 65). SLO’s motivation goes beyond this because of its responsibility for and accountability to the irreducible Other. It is a spiritual response not to improve organizational culture (Jurkiewicz and Giacalone 85) or performance (Garcia-Zamar 62) but because in the face of the Other, they touch the Infinite (Morgan 116).

The management practice of leadership should derive from a basic ethical premise: all the leader’s interests are not self-interests, or by extension organizational interests, but are, in the first instance, moral responsibilities to and for the Other (Werhane 157) because “it is through the condition of being hostage that there can be in this world pity, compassion, pardon and proximity – even the little there is, even the simple ‘After you, sir’” (Levinas 100, p. 117). For Levinas, leadership is not about role modelling ethical behavior or managing ethical processes to achieve certain organizational outcomes (Brown and Treviño 27). Rather, it is about how a leader’s interactions with employees forms their ethical self. Specifically, a leader’s conscious self-actualization depends on the alterity of the Other. Without this, the self cannot become fully human in an existential and social sense – without the Other, there is no ethical I (Arnett 6). SLO understands it is not follower adulation that is important, but their needs (Gibbs 66), and how meeting those needs teaches leaders about vulnerability, compassion, and humility.

Using management tools like ethical codes, social responsibility principles, and corporate value statements to influence decision-making offers little to leaders from Levinas’ perspective since these are typically underpinned by philosophical frameworks such utilitarianism (Audi 8) and Kantian ethics (Bowie 24), which tend to imbue leadership practice with an element of bias (e.g., it is the leader who ultimately decides what constitutes happiness/unhappiness or what constitutes a universal maxim), and when applied in a business context, inevitably results in ethics being “in the service of the self-interest of the company” (Aasland 1, p. 226). Moreover, the abstract and universal nature of such tools often totalizes individual employees and suppresses the plurality of stakeholder voices (Rhodes 128), which leads to practices with a semblance of ethicality. As an illustration, Roberts (135) cites a company social responsibility report that states: “We care about what you think about us” (p. 123). This statement conveys concern for the Other, but only to the extent, it helps the company. Such actions have little to do with ethics and could be conceived as an exercise in power, where the need to look ethical transcends any real sense of responsibility (Knights and O’Leary 90).

From a Levinasian standpoint, the management practice of leadership is not about organizing and controlling groups of people, or more specifically, strategic or human resource management, rather it is about wrestling with the demands of different stakeholders to arrive at decisions which, while not necessarily satisfying everyone, are derived based on their fairness (Knights and O’Leary 90). This raises two points. First, there is a constant tension between the infinite responsibility to others and the limitations of this within finite social contexts (Byers and Rhodes 32). Unlike other abstract approaches which tend to provide definitive answers to the dilemmas that arise from this confluence, SLO recognizes that relationships come before ‘doing ethics’ per se (Aasland 1). Therefore, SLO constantly strives to deliver justice to all even while understanding the impossibility of this requirement. Such striving leads to the second point, that such justice is grounded in a personal ethic not some abstract formula of rules or norms, which typically results in moral distance and ethical indifference (Bauman 15). In understanding justice this way, SLO attempts to consider the wider organizational community and the society it belongs to. This leads to a much fuller form of social responsibility than usually exists in the business literature, which typically is based on enlightened self-interest (Carroll and Shabana 34).

Good leadership practice (e.g., being an SLO), means accepting one’s “own fallibility and ineptitude in the face of the demands to which [leaders] are called to respond” (Rhodes and Badham 132, p. 73). This form of reflexivity allows leaders to see the flaws and hubris within themselves, while also critiquing the human folly of presuming that they leaders know everything. Good leadership practice also communicates the necessity and infinite demand of the Other, while also, “in both rhetoric and ritual, communicating its contested nature and finite limitations” (Rhodes and Badham 132, p. 86). This involves “initiating forms of rhetoric and ‘anti-rites’” (p. 87) that enable the recognition and discussion of the multiple and unresolvable demands placed on leaders. In doing this, leadership becomes subversive and transformative in the “questioning of presumed final vocabularies and associated hierarchies” (p. 87). It shifts leadership away from reinforcing existing power structures and repressing dissenting views to “speaking truth to power” by allowing these multiple “tensions to be voiced without being neutered through artificial reconciliation” (p. 87). Finally, good leadership practice involves “a reflective appreciation of both the rationality of justice and the ethics of generosity, as well as divisions within and incompatibilities between them, advocates for each, and preparedness to be outsiders-within” (p. 90). For example, an SLO might adopt a ‘layered’ approach to decision-making. Such an approach means having a ‘thin’ commitment to ethical generalities while being involved at a deeper level in local ethical action. McGhee and Grant’s (110) notion of a spiritual tempered radical has some parallels here. Such persons have broad spiritual concerns about justice for all but act at the local level in subtle ways that incrementally shift organizational cultures towards the infinite Other (and the Third) without ignoring the “contradictory nature of our moral and public spheres, the limits of our capacity to act on behalf of others” and “coupled with an enduring commitment to aspirational hopes” (Rhodes and Badham 132, p. 90).

Of course, there are limitations to a Levinasian SLO. First, as discussed earlier, there is the risk of SLO becoming a totality which assimilates all other approaches to leadership. This is avoidable if we understand SLO is not a full alternative to SL, or indeed other approaches, but instead, is an enrichment, while also being open to continual self-reflection and criticism of this style. If we fail to perform this critique, then we risk developing leadership narcissism (Roberts 135). Second, we must recognize, despite examining broad concepts like leadership, organizations, and ethics, that only individuals can embed and embody leadership. An organization “cannot experience and nourish responsibility because it has no body, no subjectivity, and no independent existence… It can neither (subjectively) recognize the Other nor feel responsibility” (Bruna and Bazin 29, p. 581). Finally, it is clear why Levinas insists ethics and the Other precede the Self given his desire to undermine the Western philosophical pre-occupation with the subject which is a legacy of the enlightenment (Knights and O’Leary 90). The issue is whether in doing so, he undermines his argument. Enlightenment philosophies make ethics dependent on the rational autonomous self, Levinas makes the rational autonomous self-dependent on ethics – it is the same argument but in reverse. As a rhetorical device, this has merit in undermining our pre-occupation with the self in post-enlightenment cultures. However, it can be problematic if “the Other cannot be recognized outside the condition of self-consciousness” (p. 135). Levinas, though, might dispute this claiming that it falls yet again into solipsism, with the Self assimilating the Other on its terms. All forms of essentialist or collaborative leadership are sooner or later undermined by such thematizing (Steiner 143).

Conclusion

If we consider leadership, and SL specifically, then it may be fair to describe it as often a hierarchical, egological, and performance-oriented phenomenon (Eicher-Catt 52). While there is certainly no denying that SLs care about their followers and the wider community, they often enact this care in such a way that these broader characteristics get reinforced. This becomes problematic when dealing with people considered ‘different’ (e.g., the disabled, Indigenous groups) or in politically complex organizations and/or communities. A Levinasian SLO is open and vulnerable to all people as infinitely Other and therefore desires to treat them as neighbors, with an unconditional ethical response that says “yes, here I am (me voici)” (Levinas 100, pp. 146, original italics). While fallible, and in need of constant reflection and evaluation, SLO offers a potentially better style of leadership for our postmodern twenty-first century.

Data Availability (data transparency)

Not applicable

Code Availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable

References

Aasland, D.G. 2007. The exteriority of ethics in management and its transition into justice: A Levinasian approach to ethics in business. Business Ethics: A European Review 16 (3): 220–226.

Aasland, D.G. 2004. On the ethics behind “Business Ethics.” Journal of Business Ethics 53: 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000039395.63115.c2.

Aasland, D.G. 2009. Ethics and economy. London: MayFlyBooks.

Alvesson, M., and H. Willmott. 2002. Identity regulation as organizational control: Producing the appropriate individual. Journal of Management Studies 39 (5): 619–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00305.

Antonakis, J., and D.V. Day. 2017. Leadership: Past, present, and future. In The Nature of Leadership, 3rd ed., ed. J. Antonakis and D.V. Day, 3–26. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Arnett, R.C. 2004. A dialogic ethic “between” Buber and Levinas: A responsive ethical “I.” In Dialogue: Theorizing Difference in Communication Studies, ed. L.A. Baxter and K.N. Cissna, 75–90. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Arnett, R.C. 2008. Provinciality and the face of the Other. In Communication Ethics: Between Cosmopolitanism and Provinciality, ed. K.G. Robert and R.C. Arnett, 69–88. New York: Peter Lang.

Audi, R. 2007. Can utilitarianism be distributive? Maximization and distribution as criteria in managerial decisions. Business Ethics Quarterly 17 (4): 593–611. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq20071741.

Avolio, B.J., D.A. Waldman, and F.J. Yammarino. 1991. Leading in the 1990s: The four I’s of transformational leadership. Journal of European Industrial Training 15 (4): 9–16.

Yukl, G. 2012. Effective leadership behavior: What we know and what questions need more attention. Academy of Management Perspectives 26 (4): 66–85. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0088.

Avolio, B.J., W.L. Gardner, F.O. Walumbwa, F. Luthans, and D.R. May. 2004. Unlocking the mask: A look at the process bywhich authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly 15 (6): 801–823.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.003.

Avramides, A. (2020). Other minds. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter ed.). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2020/entries/other-minds/

Bakan, J. 2004. The corporation: The pathological pursuit of profit and power. New York: Free Press.

Barthes, R. 1972. Mythologies (A. Lavers, Trans.). New York: Hill & Wang.

Bass, B.M. 1990. From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dymanics 18 (3): 19–31.

Bass, B.M., and R. Bass. 2008. The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications, 4th ed. New York: Free Press.

Bauman, Z. 1989. Modernity and the holocaust. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bell, E., and S. Taylor. 2003. The elevation of work: Pastoral power and the New Age work ethic. Organization 10 (2): 329–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508403010002009.

Bendell, J., and R. Little. 2015. Seeking sustainable leadership. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship 60: 13–26. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2015.de.00004.

Benson, P. 2018. The concept of the other from Kant to Lacan. Philosophy Now, 127 (August/September). Retrieved from https://philosophynow.org/issues/127/The_Concept_of_the_Other_from_Kant_to_Lacan.

Bevan, D., and H. Corvellec. 2007. The impossibility of corporate ethics: For a Levinasian approach to managerial ethics. Business Ethics: A European Review 16 (3): 208–219.

Blanch, J., F. Gil, M. Antino, and A. Rodríguez-Muñoz. 2016. Positive leadership models: Theoretical framework and research. Psychologist Papers 37 (3): 170–176.

Blok, V. 2017. Levinasian ethics in business. In Encyclopedia of Business and Professional Ethics, ed. D.C. Poff and A.C. Michalos, 1–5. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Blok, V. 2019. From participation to interruption: Toward an ethics of stakeholder engagement, participation and partnership in corporate social responsibility and responsible innovation. In International Handbook of Responsible Innovation, ed. R. von Schomberg and J. Hankins, 243–257. Northhampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bowie, N.E. 2000. A Kantian theory of leadership. Leadership and Organization Development Journal 21: 185–193.

Bowie, N. E. 2002. A Kantian approach to business ethics. In T. Donaldson., P. H. Werhane., & M. Cording. (Eds.), Ethical Issues in Business: A Philosophical Approach. (7th ed., pp. 61–71). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Bradley, Y. 1999. Servant leadership: A critque of Robert Greenleaf’s concept of leadership. Journal of Christian Education 42 (2): 43–54.

Brown, W. 2015. Undoing the demos: Neoliberalism’s stealth revolution. New York: Zone Books.

Brown, M.E., and L.K. Treviño. 2006. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly 17 (6): 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004.

Brown, M.E., L.K. Treviño, and D.A. Harrison. 2005. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 97 (2): 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002.

Bruna, M.G., and Y. Bazin. 2017. Answering Levinas’ call in organization studies. European Management Review 14 (4): 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12137.

Buber, M. 1970. I and Thou (W. Kaufmann, Trans.). New York: Touchstone.

Burns, J. 1978. Leadership. New York: Harper Row.

Byers, D., and C. Rhodes. 2007. Ethics, alterity, and organizational justice. Business Ethics: A European Review 16 (3): 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8608.2007.00496.x.

Calas, M., and L. Smircich. 1991. Voicing seduction to silence leadership. Organization Studies 12: 567–602.

Carroll, A.B., and K.M. Shabana. 2010. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. International Journal of Management Reviews 12 (1): 85–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00275.x.

Caygill, H. 2002. Levinas and the political. London: Routledge.

Chen, M. 2011. The other and the failure of philosophy. New Narratives. Retrieved from https://newnarratives.wordpress.com/issue-2-the-other/essays/the-other-the-failure-of-philosophy/.

Chiniara, M., and K. Bentein. 2018. The servant leadership advantage: When perceiving low differentiation in leader-member relationship quality influences team cohesion, team task performance and service OCB. The Leadership Quarterly 29 (2): 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.05.002.

Cohen, R. (1981). Foreword (A. Lingis, Trans.). Otherwise than Being (pp. xi-xvi). Pittsburg, Pennsylvania: Duquesne University Press.

Collinson, D. 2012. Prozac leadership and the limits of positive thinking. Leadership 8 (2): 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715011434738.