Abstract

Evidence for a relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns has started to emerge, however, to date, this literature has not been reviewed. The objective of the present study was, therefore, to review the literature examining the relationship between the use of Internet and social media and body image and eating concerns, and summarize the main findings. Databases were searched for published empirical studies examining the relationship between body image and eating concerns and Internet use. Our search identified 67 studies. The findings indicate the presence of appearance-related content on Internet and social media, including content promoting extreme body shapes or behaviors. The results from qualitative, correlational and experimental studies overall support the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns. The studies identified were grounded in three main theoretical frameworks: sociocultural, objectification theory, and social identity theory; however, other more minor frameworks were also used. The use of Internet, and particularly appearance-focused social media, is associated with heightened body image and eating concerns. Developmental characteristics may make adolescents particularly vulnerable to these effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Etiological models of body image and eating concerns have highlighted the role of the social focus on slenderness and muscularity in body image and eating concerns, and how environments that place a greater emphasis on appearance may increase the risk for these concerns (Basow et al. 2007; Klump et al. 2002; Thompson et al. 1999). In addition, research has shown how certain types of interpersonal interactions may also promote the development of body image and eating concerns (Menzel et al. 2010). Contemporary youth are increasingly engaged with, and interacting in, an online environment (Madden et al. 2013); however the effects of this on body image and eating concerns are not yet clear.

The Internet and social media present a number of characteristics that might theoretically lead them to be associated with body image and eating concerns. First, they represent a new form of mass-media, which, similarly to traditional forms of media (Tiggemann 2003), may therefore contain a high level of thin-ideal content associated with body image and eating concerns. Second, the Internet and social media are highly visual settings and encourage users to create profiles on various platforms, populated with photographs, in order to present themselves to other users. The attractiveness of individuals in online profiles has been suggested to influence their popularity and the amount and type of online interactions (Jaschinski and Kommers 2012; Peña and Brody 2014), and, consistent with this, women have been shown to use attractiveness as one of the main criteria for the images they choose to link to their online profiles (Pempek et al. 2009). This disproportionate reliance on physical appearance in the online world (perhaps to an even greater extent than offline) could be hypothesized to be associated with increased body image and eating concerns. Finally, the presence of online groups encouraging extreme weight loss and weight control behaviors such as pro-eating disorders websites may also contribute to the development or the maintenance of body image concerns and disordered eating (Rodgers et al. 2012). In sum, Internet and social media use may contribute to body image and eating concerns via multiple pathways.

In addition, the relationship between the Internet and body image and eating concerns might be particularly relevant among adolescents and emerging adults for several reasons. First, this age group is the most engaged in terms of social media use (Valkenburg and Peter 2009). Second, the Internet is relevant to a number of developmental issues that are salient in adolescence, particularly in relation to social development, such as identity, self-worth, peer relations, and health behaviors (Subrahmanyam and Greenfield 2008; Subrahmanyam and Šmahel 2011a, b; Valkenburg and Peter 2009)-aspects that are also highly relevant for body image and eating concerns. In this way, social networking has been found to strongly impact adolescent relationships (Antheunis et al. 2014; Subrahmanyam and Greenfield 2008), and the Internet has been revealed as an important space for identity creation among adolescents (Subrahmanyam et al. 2006, Subrahmanyam and Šmahel 2011b; Valkenburg et al. 2005). Furthermore, consistent with the aspects of the Internet highlighted above as relevant to the field of body image and eating concerns, within developmental psychology, the Internet has been conceptualized as a form of media, a form of communication, and a cultural tool (Greenfield and Yan 2006). Thus, there is a strong theoretical background for a relationship between Internet and social media use and body image and eating concerns among youth.

Over the last years, an emerging body of work has started to explore the hypothesized relationships between Internet and social media use empirically (Brown and Bobkowski 2011; Tiggemann and Slater 2014). However, to date, these data have not been reviewed. The objective of the present study was, therefore, to review this literature so as to provide an overview of the findings to date. While the overarching aim of the present article is to provide a summary of the existing data that will inform our understanding of the impact of Internet use among adolescents, the review is not constrained to studies among adolescents so as to provide a more complete picture of the existing data.

Methods

Relevant studies were identified by searching electronic databases including PsycInfo, ScienceDirect, and Medline, as well as Google Scholar. No time restraint was placed on the search at it was expected that most studies would be recent. In addition, the reference lists of articles were scanned for other potentially relevant articles. Key words used included “Internet,” “Online,” “Facebook,” “Social Media,” “Social Network,” “Twitter,” “Body,” “Eating,” “Self-objectification”, “self-surveillance,” “Social Comparison,” “Anorexia,” “Bulimia,” “social identity,” “Pro-ana,” “Pro-Eating.” Inclusion criteria were: published empirical articles or abstracts; in English, exploring the association between Internet use and body image and eating concerns. Review articles and theses were thus excluded. Data were collected by both authors (Table 1). The data collection form contained the following items: Authors, Date, Title, Country, Participants (N, mean (SD) age, gender), Design, Assessment of Internet or Social Media use, Outcomes, and Main Findings.

Research examining the role of media in the etiology of body image and eating concerns has highlighted a number of areas for consideration when evaluating support for this theory including: (1) the presence of appearance-related content; (2) qualitative reports of the association between exposure to this content and body image and eating concerns; (3) quantitative data supporting this relationship that are cross-section, longitudinal, and experimental (Levine and Murnen 2009). Consistent with this, the findings from our review were organized into these three areas. In each of these sections, findings relative to pro-eating disorder websites were considered separately, as they constitute an extreme form of online content, and one that is recognized as putatively deleterious, and outside of social norms.

Lastly, in addition to the data extracted above, the theoretical framework of each retained article was identified. When the theoretical framework was not explicitly stated in the introduction and rationale of the study, it was inferred from the theoretical model examined, the interpretation of findings, or the constructs assessed. An overview of the theoretical approaches used to frame the examinations of the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns in the studies identified was included in a fourth and final section of the results.

Results

Overall our search identified 67 empirical studies exploring the relationship between the Internet and body image and eating concerns (Table 1). Among the 67 identified studies, 52 collected data with study sample sizes ranging from 17 to 2036 participants. Studies were mainly conducted among children/adolescents (n = 13), college students (n = 23) and community samples (n = 12). One study was conducted among ED outpatients and one among adolescents with ED and their parents. In two studies mixed sample were reported: the first study aimed to compare a community sample and a sample of college students, and the second one included a mixed sample of adolescents and college students. Eighteen countries were represented in the studies included in this review with the majority of research conducted in the US (n = 20), Australia (n = 7), Holland (n = 4), Turkey (n = 4), and the UK (n = 4). In terms of study design, the majority of studies were correlational (n = 36), the remainder were descriptive (n = 20), experimental (n = 8) or qualitative (n = 6).

Presence of Appearance-, Body Image- and Eating-Related Content on the Internet and Social Media

Explicit Appearance and Weight Focused Content

Unlike most traditional forms of media, the Internet includes content contributed both by large multinational corporations and industry, as well as users. This is an important distinction as users, and particularly youth, may be less likely to attribute persuasive intentions to user-contributed content. Interestingly, the line is increasingly blurred between content contributed by individuals and corporations, as companies post on social media platforms, and individuals use the Internet to advance their own enterprises or garner support for various social movements. Similarly, celebrities, entertainers, or other high-profile individuals maintain their profiles on a number of social networking websites as “individuals” with the aim of promoting their work, or even “themselves” as a product (Kaplan and Haenlein 2012; Marshall 2010). One result of this is a focus on user-driven content and platforms in research as opposed content identified as commercial, likely supported by the idea that corporation-contributed online content would differ little from similar content presented on the television or billboards etc. From a developmental perspective, an important consideration is the degree of awareness of this marketing intent among youth. It has been shown that the awareness of the persuasive intent of traditional advertising (depicting a typical consumer product from a recognizable brand) may not yet be fully developed by the age of 10 (Greenfield 2004; Oates et al. 2002). Understanding the marketing intent of the Facebook profile of a celebrity (in which the individual is the product) may develop even later, at an age when children are already frequent Internet users (Wartella et al. 2005). Indeed, children and adolescents’ understanding of the complexities of the Internet, including its social aspects, has been shown to be limited (Yan 2005, 2009). As an illustration of this focus on user-contributed content, only one study has explored the content of advertisements on websites frequently used by adolescents, and revealed that the most frequently promoted products were cosmetics (Slater et al. 2012). Furthermore, the authors noted that many of the products advertised would be considered inappropriate for an adolescent audience, including weight-loss products or online dating and gambling services (Slater et al. 2012). Thus, there is preliminary evidence that corporation contributed content on the Internet contains a focus on appearance, however data are very scarce.

Regarding user-contributed content, a number of studies have suggested that it may contain a high level of appearance-related material. In addition, social media may also amplify the thin-ideal content portrayed by the media, as they allow individuals to comment on it and reinforce and normalize the pursuit of the thin-ideal. In 2013, nearly 1000 twitter messages were posted before and during the Victoria’s Secret fashion show, including tweets related to body image, eating, weight and appearance comparison (Chrisler et al. 2013). In another study exploring the presence of appearance-related content on Twitter, it was found that there was a high prevalence of words such as “fat” daily on Twitter (Fernandes et al. 2013). An analysis of fat stigmatizing videos on YouTube revealed that these videos were very frequently viewed, up to almost 14,000,000 times, and that they were often accompanied by fat-stigmatizing comments (Hussin et al. 2011). Therefore, appearance-related content appears to be frequent in user-contributed online content.

“Thinspiration” content, that is extreme thin-ideal content in the form of images of individuals with protruding bones (generally digitally modified), and messages encouraging extreme forms of weight-loss can also be found on the Internet. Much of this content is found on pro-eating disorder websites (as discussed below). The promotion of “fitness”, mainly meaning a toned and lean appearance attained through exercise and nutrition regimes is also highly prevalent on the Internet, termed “Fitspiration” content. “Fitspiration” includes objectifying images of individuals, generally portraying muscle definition on abdominals, arms, or legs, and appearance-targeted recommendations for diet and exercise behaviors. Content analyses of websites focusing on fitness have shown a high prevalence of images and messages emphasizing the importance of appearance, particularly thinness and muscularity, and promoting the use of dietary restriction through guilt and feelings of objectification (Boepple and Thompson 2015). Similarly, an analysis of 15 blogs on Tumblr authored by females with eating disorders revealed that all of the blogs contained images that could be classed as “thinspiration” and frequently included food and exercise logs (Gies and Martino 2014). Thus, high rates of appearance and eating-related content can be found on the Internet and social media.

Pro-eating Disorders

Pro-eating disorder websites present eating disorders as a life-choice rather than a severe mental-illness. Content analyses of such websites have revealed that many of them contain “thinspiration” images and content, as well as encouragement for maintaining and concealing eating disorder symptomatology (Borzekowski and Rickert 2001; Mulveen and Hepworth 2006; Ransom et al. 2010). Furthermore, many of the sites are interactive and offer forums through which participants can exchange stories or provide each other with support (Borzekowski and Rickert 2001; Mulveen and Hepworth 2006). This provision of support has been identified by members of pro-eating disorder online communities as one of the critical aspects of the groups (Brotsky and Giles 2007; Wooldridge et al. 2014). In addition, however, participants report visiting pro-eating disorder websites to obtain help in maintaining disordered eating (Csipke and Horne 2007; Gavin et al. 2008; Giles 2006), and the content of these sites often reaffirms the importance of thinness (Riley et al. 2009). Importantly, males as well as females have been shown to visit these websites (Wilson et al. 2006). Pro-eating disorder content has also been found to be prevalent on social media, including Facebook (Teufel et al. 2013). An analysis of social media content tagged as “Thinspiration” or “Thinspo” revealed that these images were generally highly objectifying, sexually suggestive, and frequently accompanied by endorsing comments (Ghaznavi and Taylor 2015).

Implicit Appearance- and Weight-Focused Content

In addition to the content described above, which presents an explicit focus on appearance, the online environment has been described as placing a more subtle emphasis on physical appearance. Indeed, adolescents have described appearance as being the central component of online presence and identity (Berne et al. 2014). Thus, physical appearance is one of the most important aspects of online self-presentation. Furthermore, the Internet provides a space in which an unusual amount of control can be exerted over one’s “appearance,” which can, therefore, be enhanced or manipulated and molded according to peer feedback. It has been proposed that the anonymity of the Internet as well as the heightened control over interactions and their pace may promote adolescents using this space for identity development purposes (Valkenburg et al. 2005). The above findings suggest that such online identity experiments may include modifying appearance in particular. However, adolescents have also emphasized the gendered aspects of seeking positive appearance-feedback online and the fact that this is socially acceptable mainly for girls (Berne et al. 2014), suggesting that gendered scripts extend to the online environment. In addition, research has found that adolescents modify the pictures of themselves that they post online to more closely resemble to social ideal (Siibak and Hernwall 2011), thereby also replicating social scripts. In this way, somewhat paradoxically, the additional control over self-presentation offered by the Internet results in appearance being one of the most salient dimensions of adolescents’ online presence.

More hurtful forms of online interpersonal feedback exist in the forms of cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is highly prevalent among adolescents, and almost 90 % of teenagers reporting knowing a friend who had been targeted (Hoff and Mitchell 2009). Among 15-year olds, appearance-based cyberbullying was perceived to be frequent, and an unavoidable part of using social media platforms such as Facebook or Instagram (Berne et al. 2014), and most prevalent among girls (Hoff and Mitchell 2009). Consistent with theories of bullying in the offline world (Garandeau et al. 2014), cyberbullying was perceived to be motivated by desire for social status, or sensation seeking (Berne et al. 2014; Hoff and Mitchell 2009; Wegge et al. 2014). Thus, cyberbullying constitutes a particularly harmful type of online appearance-related interaction.

Qualitative Data

To date, few studies have qualitatively explored the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns. However, the existing data point to an association, and highlight the role of social comparison processes. In a study among US Young adults, participants reported greater levels of body image concerns related to Facebook (such as being self-conscious when viewing photos one oneself on Facebook, or feeling motivated to change one’s appearance after comparing oneself with pictures of others on Facebook) compared to older adults (Hayes et al. 2015). Furthermore, in a sample of US undergraduate Facebook users, almost 10 % of the female participants agreed that pictures other people posted on Facebook “gave them a negative self body image,” thus implicitly referring to decreases in body satisfaction resulting from social comparison (Thompson and Loughleed 2012). Similarly, among female college students in Kuwait, over 20 % reported having dieted to lose weight “because of using Internet” (Musaiger and Al-Mannai 2013). Thus, the existing qualitative data support an association between Internet and social media use and body image and eating concerns.

Qualitative data from pro-eating disorder website users have also suggested an association between exposure to these websites and body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Studies have revealed that pro-eating disorder website users reported learning a range of new information and behaviors, and using new methods of weight loss, purging, symptom concealment (Jett et al. 2010; Ransom et al. 2010; Wilson et al. 2006). These findings, therefore, suggest a direct association between exposure to pro-eating disorder online content and engagement in eating disorder behaviors.

Overall, qualitative data regarding the relationship between Internet and social media use and body image and eating concerns are scarce. However, the existing data in the literature do support this relationship. Furthermore, these data highlight the impact of social media in particular.

Quantitative Data

Correlational and Longitudinal Studies

A number of correlational studies have now examined the relationship between Internet and social media use, and body image and eating concerns. Some of these have explored Internet use in general, while others have focused more specifically on certain social media platforms that allow individuals to engage more actively with the online environment. Finally, a small number of studies have examined the relationship between more extreme pro-eating disorder content and body image and eating concerns.

General Internet Use

A growing number of studies have reported a relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns. Among US female undergraduates, exposure to the Internet was associated with eating pathology, although the effect was small. Furthermore, this effect was fully mediated by the internalization of the thin-ideal (Bair et al. 2012). Similarly, among a sample of Chinese adults, Internet access was associated with subjective beliefs of fatness as well as concern about loss of control over food; however these relationships were not found among the comparison adolescent sample (Peat et al. 2014). Among a large sample of Australian 13–15 year olds, Internet exposure was associated with thin-ideal internalization, body surveillance, and drive for thinness (Tiggemann and Slater 2013). Similarly, among Australian pre-adolescents, time spent online was associated with thin-ideal internalization, body surveillance, dieting, and lower body esteem (Tiggemann and Slater 2014). In addition, among Australian pre-adolescents, Internet exposure was associated with self-objectification, which in turn was associated with body shame, dieting and depressive symptoms (Tiggemann and Slater 2015). Regarding more specific types of Internet content and body image and eating concerns, among a representative sample of Dutch individuals, exposure to sexually explicit online content was associated with increased body dissatisfaction 6 months later among males; however no associations were found among female respondents (Peter and Valkenburg 2014). Among French young women, Internet use was associated with body shame, body image avoidance and bulimic symptoms, although not body surveillance or body dissatisfaction (Melioli et al. 2015). Thus, while the data reveal some divergences, overall the relationship between general Internet use and body image and eating concerns is supported.

Interestingly, a larger body of work has investigated the relationship between problematic Internet use (or Internet addiction) and body image and eating concerns, and provided support for this relationship among a number of diverse populations. Thus, problematic Internet use has been found to be associated with body image concerns among Hungarian individuals aged 14–34 (Koronczai et al. 2013), Turkish college students (Ceyhan et al. 2012), Chinese adolescents and young adults (Tao 2013; Tao and Liu 2009), French young men and women (Rodgers et al. 2013), and US male undergraduates, although the relationship was not replicated among female participants (Hetzel-Riggin and Pritchard 2011). In addition, problematic Internet use has been found to be associated with disordered eating among Turkish high school students, and college students (Alpaslan et al. 2015; Çelik et al. 2015), Chinese adolescents and young adults (Tao 2013; Tao and Liu 2009), and French young men although not women (Rodgers et al. 2013). Problematic Internet use was also associated with drive for thinness among a sample of US female eating disorder outpatients (Claes et al. 2012). However, in contrast to these findings, a study among just under 2000 Turkish adolescents aged 14–18 years found no relationship between weekly Internet use, Internet addiction scores and disordered eating (Canan et al. 2014). In sum, the relationship between problematic Internet use and body image and eating concerns has also been overall supported.

Social Media

A number of studies have investigated the relationship between social media use and body image and eating concerns among adolescents and young adults. Among Australian high school students, exposure to appearance-related content on the Internet, and principally social media, was associated with drive for thinness and lower weight satisfaction (Tiggemann and Miller 2010). In addition, out of 11 popular websites, Facebook was the social media platform found to be most strongly associated with body image concerns (Tiggemann and Miller 2010). Similarly, among a large sample of Australian 13–15 year olds, Facebook users reported higher levels of body image concerns than non-users (Tiggemann and Slater 2013). Among a sample of over 600 Dutch adolescents aged 11–18, social media use was associated with both appearance investment and desire for cosmetic surgery (de Vries et al. 2014). Finally, among a sample of Belgium female adolescents, exposure to sexually objectifying content on social media was associated with self-objectification and body surveillance (Vandenbosch and Eggermont 2012). Therefore, social media use, and particularly Facebook, has been associated with increased body image concerns in adolescents.

Regarding young adults, among US female college students, duration of Facebook use was associated with disordered eating (Mabe et al. 2014), and Facebook involvement was found to be associated with objectified body consciousness, which in turn was associated with body shame (Manago et al. 2015). Similarly, among a sample of French young women, body image avoidance and disordered eating were associated with social networking website use; however these relationships were not replicated among young men (Rodgers et al. 2013). The relationship between social media use and body image and eating concerns has thus also been supported in young adults.

It has been suggested that one of the mechanisms accounting for the association between social media use and body image and eating concerns is appearance comparison. If this were the case, it would be expected that engaging in more appearance comparison while using social media would result in greater body image and eating concerns, and furthermore, that engaging with social media features that facilitate or encourage such comparisons would also be more strongly related to body image and eating concerns. Consistent with this, among US female adolescents, the use of appearance-related Facebook features (mainly photo-related features) was associated with internalization of the thin ideal, self-objectification, drive for thinness, and low weight satisfaction, whereas general Facebook use revealed no association with body image and eating variables (Meier and Gray 2014). In a sample of US young adults, time spent on social media was not associated with body image concerns; however the amount of time on Facebook spent engaged in activities such as commenting on others’ profiles or photos was associated with drive for thinness and appearance comparison (Kim and Chock 2015). Among Australian female college students, Facebook usage was associated with body image concerns (Fardouly and Vartanian 2015). Furthermore, this relationship was mediated by appearance comparisons with peers and celebrities (Fardouly and Vartanian 2015). Similarly, among a sample of UK adolescents and young women aged 17–25 years old, Facebook usage was associated with high self-objectification, and this relationship was mediated by comparisons with one’s peers on Facebook (Fardouly et al. 2015a). Finally, among a sample of 800 US men, self-objectification was associated with time spent on social networking sites, and time spent editing photos for social networking site (Fox and Rooney 2015). In sum, social comparison has been supported as one of the mechanisms through which social media use impacts upon body image and eating concerns.

Attention has also been paid to negative feedback received on social media sites. In an innovative study, researchers coded participants’ status updates posted on Facebook during a 31-day period, as well as other users’ responses to these updates. Findings revealed that receiving negative comments in response to status updates concerning personal life was associated with higher levels of weight, shape, and eating concerns at the end of the 31 day period (Hummel and Smith 2015). In addition, individuals who tended to seek feedback on Facebook but received negative feedback reported higher levels of dietary restraint (Hummel and Smith 2015). Similarly, among a sample of female college students, maladaptive Facebook usage, defined as using Facebook for social comparison or negative self-evaluation purposes, predicted increases in bulimic symptoms and episodes of over-eating 4 weeks later (Smith et al. 2013). Regarding more aggressive forms of negative feedback, cyberbullying has been found to be associated with lower body esteem among a sample of over 1000 Swedish children and adolescents aged 10, 12, and 15 years (Frisén et al. 2014). In this way, receiving negative feedback from others on social media has also been associated with high body image and eating concerns.

Pro-eating Disorders

A small number of studies have examined the relationship between exposure to pro-eating disorder websites and body image and eating concerns. In the only study conducted among adolescents aged 13, 15 and 17, visiting pro-anorexia websites was associated with high drive for thinness, body dissatisfaction and perfectionism (Custers and Van den Bulck 2009). Among college women, exposure to pro-anorexia websites was associated with decreased caloric consumption during the week following exposure (Jett et al. 2010), and more frequent pro-eating disorder website viewing was associated with higher levels of body dissatisfaction, drive for thinness and bulimic symptoms (Harper et al. 2008). Similarly among male and female undergraduates, the internalization of pro-anorexia messages was associated with drive for thinness and drive for muscularity (Juarez et al. 2012), and among users of pro-eating disorder websites, higher levels of website usage were associated with higher levels of disordered eating (Peebles et al. 2012). These findings have, therefore, provided support for the hypothesized relationship between exposure to pro-eating disorder websites and body image and eating concerns.

Thus, a number of correlational studies have examined the relationship between various types of Internet use, and body image and eating concerns. Together, these studies have provided emerging evidence that a number of different aspects of Internet use might be associated with higher body image and eating concerns. Furthermore, studies focusing on social media in particular have highlighted the role of appearance comparison as a critical mechanism accounting for the relationship between social media use and body image and eating concerns. In sum, this literature therefore supports and clarifies the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns.

Experimental Studies

The Internet and Social Media

Experimental studies exploring the effects of exposure to the Internet on body image and eating concerns have focused on specific types of websites, principally social media platforms such as Facebook, and pro-eating disorder content. One study, in a sample of US young adults, mimicking the content of social media platforms in general, exposed participants to images of very attractive Internet users or somewhat unattractive users. Participants exposed to images of attractive Internet users reported lower levels of body satisfaction following exposure compared to those who viewed images of unattractive users (Haferkamp and Krämer 2011). Thus, given the rates of images of individuals held to be attractive on social media, exposure to social media may increase body image concerns.

Experimental studies focusing on the effects of exposure to Facebook have examined the effect of exposure to Facebook content (real or mock) compared to comparison websites. Among a sample of British young women, exposure to their own Facebook profile for 10 min resulted in greater negative mood compared to the comparison websites, although not greater body dissatisfaction (Fardouly et al. 2015b). In addition, however, participants with high trait levels of social comparison reported more facial, hair, and skin-related discrepancies after exposure to Facebook compared to the comparison websites, suggesting that Facebook exposure may increase concerns related to facial attractiveness as opposed to body weight and shape (Fardouly et al. 2015b). Among a sample of female US college students, those assigned to view their own profile, as opposed to a neutral website (Wikepedia), maintained their initial levels of weight and shape concerns, and anxiety, while those assigned to the comparison condition reported decreased levels at post-test (Mabe et al. 2014). Examining the role of specific types of Facebook content, a cross-cultural study explored the effects of exposing a sample of US female college students and a sample of Japanese female college students to mock Facebook profiles containing fat talk which either encouraged or discouraged weight loss (Taniguchi and Lee 2012). Findings revealed that among Japanese students, those who witnessed weight-loss-promoting profiles reporting lower body satisfaction compared to those who witnessed weight-loss-discouraging profiles; however, there were no differences between conditions in the American sample (Taniguchi and Lee 2012). In sum, the existing experimental data overall support a relationship between Facebook exposure and body image and eating concerns.

One team of researchers created protocols replicating the creation of an online profile as occurs on social networking sites, thus exploring the effects of contributing to social media rather than exposure to it. In a study, framed as an investigation of consumer choices, Dutch young women were invited to rate two advertisements that were either neutral or objectifying (lingerie). They then created an online profile which they were either told was private or would be accessible to others (audience manipulation) (de Vries and Peter 2013). Findings revealed that the audience manipulation was associated with significant differences in the amount of self-objectifying statements referring to physical appearance included in the profiles generated by participants, with profiles intended for an audience containing more of these statements, suggesting that the creation of a profile to be viewed by others increased participants’ feelings of self-objectification (de Vries and Peter 2013).

Pro-eating Disorders

A small number of experimental studies have examined the effects of exposure to pro-eating disorder content on subsequent body image and eating concerns. In a pilot study, a small sample of female undergraduates were exposed to either a specifically constructed “pro-anorexia” website, a home décor website, or a female fashion website (Bardone-Cone and Cass 2006). Findings revealed that, compared to participants who viewed the home décor or female fashion websites, those exposed to the pro-anorexia website reported more negative affect and feelings of being overweight, and lower self-esteem, perceived attractiveness and appearance self-efficacy at the trend level (Bardone-Cone and Cass 2006). In a second larger study with a similar design, study participants exposed to the pro-anorexia website reported higher levels of negative affect, lower self-esteem, perceiving themselves as heavier, engaging in more social comparison, and being more likely to exercise and think about their weight in the future, compared to those viewing one of the comparison websites (Bardone-Cone and Cass 2007). In a third study, building upon this design, Dutch young women were allocated to view one of the three specifically constructed websites described above or a fourth one promoting self-injury (Delforterie et al. 2014). Findings revealed that scores on one of the three body image measures differed between the pro-anorexia condition and the comparison conditions, however, they also revealed participants exposed to the pro-anorexia websites to be more satisfied with their appearance, which contrasted with findings from the two previous studies (Delforterie et al. 2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis identified nine studies examining the effect of exposure to eating disorder websites on eating pathology, and concluded that there was a small to large effect on different eating disorder symptoms (Rodgers et al. 2015). In sum, the existing experimental data point to the deleterious effects of exposure to pro-eating disorder content on body image and eating concerns.

Theoretical Backgrounds

Three main theoretical frameworks were identified as being used as grounding frameworks for the studies included in this review: Sociocultural theory (n = 39), self-objectification theory (n = 11), and social identity theory (n = 13). As the theoretical underpinnings of these frameworks have been described in detail elsewhere (Rodgers 2015) they will be presented only very briefly here. Four more minor theoretical frameworks were also identified: body image avoidance theory (n = 5), addiction/self-regulation theory (n = 5), interpersonal theory (n = 1), and sedentarity (n = 1).

Sociocultural Theory

Cultivation

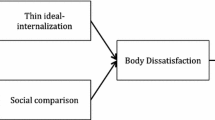

The sociocultural theory of body image and eating concerns emphasizes the role of messages from media and interpersonal influences such as peers and parents on body image and eating concerns (Thompson et al. 1999). More specifically, messages regarding the importance of pursuing the social-promoted thin-and muscular ideal received from these sources of influence are internalized by individuals, and, in conjunction with appearance comparison processes, result in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating (Keery et al. 2004; Rodgers et al. 2014; Sinton et al. 2012). For a number of reasons, adolescent girls and young women may be particularly vulnerable to these processes. First, the social ideal presented is a very youthful one, and as individuals tend to engage in comparisons with age-appropriate targets this may make youth more vulnerable (Tiggemann 2004). Secondly, adolescence is an important time for identity development and girls may look to the media as a source of role models or practical information regarding the ways in which to conform to social gender scripts and appearance norms (Lloyd 2002; Thompson et al. 2004). In addition, adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to peer pressure and appearance feedback from peers and parents (Jones et al. 2004).

The studies identified in this review that were grounded in sociocultural theory highlighted the presence of appearance and thin-and-muscular content on the Internet, which frequently portrayed objectified bodies, and emphasized the importance of the pursuit of the thin-and-toned ideal (Boepple and Thompson 2015; Slater et al. 2012), sometimes with extreme “thinspiration” or “fitspiration” content (Boepple and Thompson 2015). In addition, messages regarding eating and exercise were often constructed so as to increase feelings of guilt as a means of motivating individuals to engage in body change behaviors (Boepple and Thompson 2015). The high prevalence of fat-stigmatizing content on social media has also been studied within this framework, illustrating the saturation of the media environment with these messages (Hussin et al. 2011). Therefore, the existing data confirm of the presence of appearance-related online content, which may then result in youth endorsing the importance of appearance and internalizing the thin and muscular appearance ideals.

Internet and social media and exposure has been conceptualized as exposure to appearance pressures within sociocultural theory, and has been shown to be associated with appearance investment, desire for cosmetic surgery (de Vries et al. 2014), as well as body image and eating concerns among a variety of demographic groups (Mabe et al. 2014; Meier and Gray 2014; Musaiger and Al-Mannai 2013; Peat et al. 2014; Tiggemann and Miller 2010; Tiggemann and Slater 2013), although the relationship between frequency of general internet use and disordered eating has not always been supported (Melioli et al. 2015). Exposure to images of attractive individuals or sexually explicit material on the Internet has been associated with lower body satisfaction (Haferkamp and Krämer 2011; Peter and Valkenburg 2014). Exposure to the extreme forms of pro-eating disorder content has also been shown to be associated with body image and eating concerns (Bardone-Cone and Cass 2006, 2007; Delforterie et al. 2014; Harper et al. 2008; Jett et al. 2010; Juarez et al. 2012; Rodgers et al. 2015). Thus, from a sociocultural perspective, the Internet, as a form of media influence, has been shown to be associated with higher body image and eating concerns.

Regarding the presence of messages from other sources of pressure on the Internet, studies have highlighted the presence of peer influence and fat-talk on social media (Chrisler et al. 2013; Fernandes et al. 2013; Gies 2008). Furthermore, exposure to peer comments encouraging weight-loss was associated with higher body dissatisfaction (Taniguchi and Lee 2012). More extreme peer influences in the form of cyberbullying have also shown an association with body image concerns (Frisén et al. 2014). In this way, the Internet could also be considered as a form of peer influence, and has revealed as association with body image and eating concerns.

Regarding the role of appearance comparison, one of the two important mechanisms accounting for the effect of sociocultural influences on body image and eating concerns, research has supported its role within the online environment. Social comparison with images of others posted on social networking sites has been shown to be associated with increased body dissatisfaction (Fardouly et al. 2015b; Hayes et al. 2015; Thompson and Loughleed 2012). In addition, appearance comparison has been shown to mediate the relationship between engagement in commenting on others’ profiles and pictures on Facebook and Facebook use, and body image concerns among US young adults (Fardouly et al. 2015a; Kim and Chock 2015). Maladaptive Facebook use (for example for social comparison purposes) has also been associated with increases in bulimic symptomatology over time (Smith et al. 2013). Finally, social media may allow individuals to be exposed to evidence of the social comparison engaged in by others (Chrisler et al. 2013), thus normalizing and supporting upward social comparisons with models or media images. Internalization of media-ideals, mainly the thin-ideal, the second important mechanism in sociocultural theory accounting for the impact of sociocultural sources of influence on body image and eating concerns, has also received support as a mediator of the effects of Internet use on body image and eating concerns. Internalization has been shown to mediate the relationship between Internet exposure and body image concerns and disordered eating (Bair et al. 2012; Tiggemann and Miller 2010; Tiggemann and Slater 2014). In sum, the mechanisms through which traditional media and peer influences have been shown to impact body image and eating concerns have been shown to play a similar role in the relationship between Internet and social media use and body image and eating concerns.

Social Learning

In addition to their role as socialization agents, and in line with developmental theories, the media, peers, and family members may exert a direct influence on eating behaviors through modeling and social learning (Bandura 1962; Kichler and Crowther 2009; Rodgers and Chabrol 2009). A number of studies examining the relationship between exposure to pro-eating disorder content and body image and eating concerns have adopted this social learning perspective, whereby behaviors and attitudes are learned through observation and modeling (Bandura 1962). Consistent with this, individuals have described learning new eating disorder behaviors on pro-eating disorder websites and subsequently using them, thus exacerbating or maintaining their own symptoms (Borzekowski and Rickert 2001; Ransom et al. 2010; Wilson et al. 2006), and more frequent use of these websites was associated with higher levels of disordered eating (Peebles et al. 2012). Thus, the Internet has also been shown to model eating disorder behaviors that are then learned by youth.

In sum, sociocultural theories represent the most frequently used theoretical framework to date for examining the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns. A number of the principal aspects of the theory, such as the mediating role of internalization and appearance comparison in the relationship between sociocultural influences and body image and eating outcomes, have been supported in the online environment. These findings suggest that it is a promising framework for these investigations.

Self-Objectification Theory

Self-objectification theory posits that the awareness of being subjected to the sexually objectifying male gaze results in women, and increasingly men, considering themselves as sexual objects (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). This internalized self-objectification has been shown to be associated with body image concerns and disordered eating (Moradi and Huang 2008). An important concept of this theory is that of body surveillance, referring to attention directed to controlling the appearance of one’s body to others (McKinley 1996). From a developmental perspective, adolescence is an important time for self-objectification as it is hypothesized that the sexual objectification of girls’ bodies increases sharply as they reach puberty, and that the physical changes resulting from puberty are accompanied by increasing self-objectification (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). In addition, the access to sexually explicit online content might be associated with early sexual priming, which could increase self-objectification at an earlier age (Greenfield 2004)

Objectification theory has been used to frame studies exploring online content such as “thinspiration” content on Twitter (Ghaznavi and Taylor 2015). In addition, objectification theory has been used in studies exploring the relationship between poor body image and the attention paid to photos of oneself shared online (Fox and Rooney 2015). Furthermore, experimental studies have suggested that the personal profile format, so frequently encountered on social networking websites, may be associated with self-objectification, through the awareness of being evaluated by other users (de Vries and Peter 2013).

Internet exposure has been shown to be associated with body surveillance among female adolescents and pre-adolescents, and male and female college students (Fardouly et al. 2015a; Manago et al. 2015; Meier and Gray 2014; Tiggemann and Slater 2013, 2014), as well as with body shame among young adults (Melioli et al. 2015). In addition, in this last study, body shame mediated the relationship between Internet use and bulimic symptoms (Melioli et al. 2015). Furthermore, engagement in photo-related activities on Facebook, as opposed to general Facebook use, has shown the most consistent relationship with body image and eating concerns (Meier and Gray 2014), which provides support for the idea that constant self-monitoring and the appraisal by others of one’s online appearance may increase self-objectification. Moreover, consistent with the pathways predicted by objectification theory, among a sample of Australian pre-adolescents, Internet exposure was associated with self-objectification, which itself predicted body shame, which in turn predicted both dieting and depressive symptoms (Tiggemann and Slater 2015). Finally, exposure to sexually objectifying content on social media sites was associated with self-objectification and body surveillance (Vandenbosch and Eggermont 2012).

The findings described above suggest that self-objectification theory has emerged as a useful framework for the examination of the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns. In addition, recent efforts to integrate aspects of self-objectification and sociocultural theory (Fitzsimmons-Craft 2011) are reflected in the fact that some studies have used the intersection of both these frameworks to guide their investigations (Meier and Gray 2014; Tiggemann and Slater 2013, 2014).

Social Identity Theory

Social identity theory emphasizes how identity is created through group memberships (Tajfel 1982). Adolescence is a period when individuals spend an increasing amount of time with peers, and it is, therefore, characterized by an increased striving for acceptance by, and popularity with, the peer group (Dijkstra et al. 2013). Consistent with this, adolescents have reported using the Internet to seek out appearance related feedback and compare themselves to others (Berne et al. 2014), and being knowledgeable in terms of the gendered appearance scripts to reproduce to obtain the most positive feedback (Siibak and Hernwall 2011). In addition, cyberbullying has often been considered from a social identity perspective (Berne et al. 2014; Hoff and Mitchell 2009). Thus, social identity theory has been shown to be relevant to the study of the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns.

Explorations of pro-eating disorder websites have conceptualized within a “group identity” framework, highlighting how these online groups develop a common identity, reinforced by the perceived hostility of the outgroup (proponents of eating “disorders”), and the provision of social support to ingroup members (Brotsky and Giles 2007; Giles 2006; Riley et al. 2009; Teufel et al. 2013; Wooldridge et al. 2014). A high proportion of eating disorder patients utilize these websites (Wilson et al. 2006). In addition, on some websites, pro-anorexia as a life choice is presented as being qualitatively different from the medical diagnosis of Anorexia Nervosa due to the element of awareness and free-choice (Csipke and Horne 2007; Mulveen and Hepworth 2006). This identity is strengthened through the normalization of pro-eating disorder thoughts and behaviors (Gavin et al. 2008). Studies have also highlighted how regarding these eating behaviors as a lifestyle may also encourage or maintain them, as illustrated by the association between visiting these websites and body image and eating concerns (Custers and Van den Bulck 2009). These findings have confirmed the usefulness of social identity theory in extending our understanding of the impact of pro-eating disorder websites.

In sum, to date, the social identity framework has been most frequently used to examine the effects of pro-eating disorder content on body image and eating concerns. However, there is emerging evidence that this approach is also useful in understanding how adolescents use the Internet in the processes associated with the development of body image.

Other Theoretical Frameworks

Body Image Avoidance Theory

Theories of the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns that highlight the role of body image avoidance posit that a preference for computer-mediated communication in which physical appearance is most often hidden, due to negative feelings about one’s appearance or social anxiety, may, over time, increase body image concerns through avoidance (Rodgers et al. 2013). In support of this theory, it has been found that the effect of body dissatisfaction on Internet addiction was mediated by poor problem solving skills and depressive symptoms (Ceyhan et al. 2012; Koronczai et al. 2013). Furthermore, weight preoccupation was found to be associated with problematic Internet use among young men (Hetzel-Riggin and Pritchard 2011). In addition, social media and general Internet use have been found to be associated with body image avoidance (Melioli et al. 2015; Rodgers et al. 2013). Therefore, there is preliminary support for the usefulness of considering the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns within a body image avoidance framework.

Addiction, Self-Regulation, Impulsivity

A few studies have considered that the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns might be due to common underlying self-regulation deficits (Wilson 2010). Consistent with this, findings have supported the relationship between compulsive and addictive Internet use, and disordered eating (Alpaslan et al. 2015; Claes et al. 2012; Tao 2013; Tao and Liu 2009), although one study found no evidence of a relationship between Internet addiction and disordered eating (Canan et al. 2014). Thus, overall, findings have confirmed that considering self-regulation deficits might help clarify the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns.

Other Theories

One study identified by our review was grounded in the interpersonal theory of eating disorders (Rieger et al. 2010) and revealed that feedback on Facebook has been shown to be associated with higher levels of body image and eating concerns at a later date (Hummel and Smith 2015). In another study it was hypothesized that the sedentariness and social isolation associated with spending long amounts of time on the Internet might be associated with weight gain, which would mediate the relationship with disordered eating (Çelik et al. 2015). To date however, the data from these theoretical standpoints are scarce.

Discussion

Findings from the present review provide empirical support for the presence of high levels of thin-ideal and appearance focused content on the Internet, as well as the relationship between Internet and social media use and body image and eating concerns. Furthermore, engaging with certain aspects of the Internet that are likely to increase social comparison such as photo-related activities (posting, commenting, tagging, etc.), or viewing content likely to reinforce the importance of pursuing the thin-ideal such as thinspiration and fitspiration content may be most strongly related to body image and eating concerns. To date, less attention has been paid to individual characteristics that might render youth more vulnerable to the effects of Internet use on body image and eating concerns. It has been suggested that individual patterns of social media use may vary, with some individuals likely to be frequent active contributors and other more occasional passive users (Alarcón-del-Amo et al. 2011). Extending these approaches to explore the individual characteristics and patterns of Internet use that might be most strongly related to body image and eating concerns could be a fruitful direction.

The three main theoretical frameworks that have been used to conceptualize the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating having found emerging support for the relationship; however, each proposes different mechanisms. Sociocultural theory proposes that this relationship occurs through the amplification of social messages regarding the importance of attaining a thin and toned physical appearance; self-objectification and feminist theory highlights the importance of feeling evaluated and objectified by others; and social identity theory articulates the importance of social categorization and group membership. While the majority of the existing work has been conducted within a sociocultural framework, an emerging body of evidence has lent initial support to considering these relationships within other theoretical frameworks. Each of these frameworks may present strengths in the examination of the relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns and an integrated model capitalizing on these strengths has been presented (Rodgers 2015).

Regardless of theoretical grounding, methodological challenges exist regarding our limited ability to date to assess Internet and social media use and engagement. Traditional questions regarding the amount of time spent engaged with media start to make little sense in a world where youth are permanently and simultaneously connected to their online networks through multiple mobile devices, receiving status updates from friends, blogging, tweeting, and posting on various platforms. Critically, one of the few studies that has explored “online multi-tasking” among 12 year old girls found it to be associated with lower well-being (Pea et al. 2012). Similarly, methods of capturing the quality as opposed to the quantity of online engagement and interaction might help increase our understanding of the effects of the Internet on body image and eating concerns. Thus, improving our assessment of Internet use is a critical methodological focus.

In view of the emerging evidence for the relationship between Internet and social media use and body image and eating concerns, another important area of consideration is the development of appropriate prevention strategies. One approach would be to adapt and extend existing successful prevention programs to include the Internet among the targeted risk-factors. Much of the content from media literacy programs could be easily tailored to include online advertising and content. Other aspects of the Internet, however, may call for specifically designed prevention programs. Previous research has suggested that, for example, viewing a video highlighting the use of make up and digital altering techniques before viewing a music video can buffer against the detrimental effects of media on body satisfaction (Quigg and Want 2011). However, a similar short media literacy intervention highlighting the use of digital modification on pictures posted on Facebook failed to protect against the negative effects of viewing on body satisfaction (Bardone-Cone and Karam 2013). These findings suggest that efforts should be made to design and develop successful prevention interventions specifically targeting the Internet and social networking in addition to integrating the Internet into the content of existing successful programs.

More broadly, the field of body image and eating disorders needs to consider these concerns within the changing communication landscape. A particular focus on youth is warranted, as they represent the age group both the most vulnerable to body image and eating concerns and most engaged with mobile technology and social media (Levine and Murnen 2009). In view of the speed of the development of social media, there is a need to correspondingly accelerate our understanding of the effects of new forms of communication and interpersonal relations. In addition, there is a need to accelerate the translation of research findings into practice and potentially policy. The present generation is the first to experience the world through the lens of mobile technology (both literally and figuratively). Therefore, there is no accumulated intergenerational knowledge to be passed down on how best to negotiate these aspects, and adolescents are creating new shared norms (Greenfield and Yan 2006). Simultaneously, as cultural critics, it is important to retain an integrative overview and reflection about the ways in which young women relate to media and to each other through media.

In addition, research is warranted on opportunities afforded by the Internet to forge positive body image through the exploration of different online identities, the creation of counter-cultures, the diversification of gender roles and the provision of social support. If the initial feminist optimism that the Internet would provide an escape from the objectifying male gaze and patriarchal discourse has somewhat dimmed (Fahs and Gohr 2012), it need not be entirely abandoned. Studies exploring positive body image as related to Internet use are needed.

Conclusion

The existing data support a relationship between Internet use and body image and eating concerns, and adolescents may be particularly vulnerable to the impact of the Internet. In particular, engagement with visual, appearance-focused social media platforms is associated with heightened concerns. Researchers and clinicians should continue to explore how Internet can contribute to empowering young women, and how they can contribute to making the online world a positive space. The Internet offers opportunities for online activism, which has the capacity of reaching more people in a shorter time-span than any other form. These opportunities should be capitalized on to work towards social change and move away from the focus on the thin-ideal online and offline.

References

Alarcón-del-Amo, M.-d.-C., Lorenzo-Romero, C., & Gómez-Borja, M.-Á. (2011). Classifying and profiling social networking site users: A latent segmentation approach. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(9), 547–553. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0346.

Alpaslan, A. H., Koçak, U., Avci, K., & Taş, H. U. (2015). The association between internet addiction and disordered eating attitudes among Turkish high school students. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 1–8. doi:10.1007/s40519-015-0197-9.

Antheunis, M. L., Schouten, A. P., & Krahmer, E. (2014). The role of social networking sites in early adolescents’ social lives. The Journal of Early Adolescence,. doi:10.1177/0272431614564060.

Bair, C. E., Kelly, N. R., Serdar, K. L., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2012). Does the Internet function like magazines? An exploration of image-focused media, eating pathology, and body dissatisfaction. Eating Behaviors, 13, 398–401. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.06.003.

Bandura, A. (1962). Social learning through imitation. In M. R. Jones (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 211–274). Oxford: University of Nebraska Press.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., & Cass, K. M. (2006). Investigating the impact of pro-anorexia websites: A pilot study. European Eating Disorders Review, 14(4), 256–262. doi:10.1002/erv.714.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., & Cass, K. M. (2007). What does viewing a pro-anorexia website do? An experimental examination of website exposure and moderating effects. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(6), 537–548. doi:10.1002/eat.20396.

Bardone-Cone, A. M., & Karam, A. M. (2013). Facebook and the effect of a media litteracy intervention on body dissatisfaction. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Eating Disorder Research Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

Basow, S. A., Foran, K. A., & Bookwala, J. (2007). Body objectification, social pressure, and disordered eating behavior in college women: The role of sorority membership. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 394–400. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00388.x.

Berne, S., Frisén, A., & Kling, J. (2014). Appearance-related cyberbullying: A qualitative investigation of characteristics, content, reasons, and effects. Body Image, 11(4), 527–533. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.08.006.

Boepple, L., & Thompson, J. K. (2015). A content analytic comparison of fitspiration and thinspiration websites. International Journal of Eating Disorders. doi:10.1002/eat.22403.

Borzekowski, D. L. G., & Rickert, V. I. (2001). Adolescent cybersurfing for health information: A new resource that crosses barriers. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 155, 813–817. doi:10.1001/archpedi.155.7.813.

Borzekowski, D. L., Schenk, S., Wilson, J. L., & Peebles, R. (2010). e-Ana and e-Mia: A content analysis of pro–eating disorder web sites. American journal of public health, 100(8), 1526.

Brotsky, S. R., & Giles, D. (2007). Inside the “Pro-ana” community: A covert online participant observation. Eating Disorders, 15(2), 93–109. doi:10.1080/10640260701190600.

Brown, J. D., & Bobkowski, P. S. (2011). Older and newer media: Patterns of use and effects on adolescents’ health and well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 95–113. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00717.x.

Canan, F., Yildirim, O., Ustunel, T. Y., Sinani, G., Kaleli, A. H., Gunes, C., & Ataoglu, A. (2014). The relationship between Internet addiction and body mass index in Turkish adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(1), 40–45. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0733.

Çelik, Ç. B., Odacı, H., & Bayraktar, N. (2015). Is problematic internet use an indicator of eating disorders among Turkish university students? Eating and weight disorders-studies on anorexia. Bulimia and Obesity, 20(2), 167–172. doi:10.1007/s40519-014-0150-3.

Ceyhan, A., Ceyhan, E., & Kurtyilmaz, Y. (2012). The effect of body image satisfaction on problematic Internet use through social support, problem solving skills and depression. The Online Journal of Counselling and Education, 1(3), 83–95.

Chrisler, J. C., Fung, K. T., Lopez, A. M., & Gorman, J. A. (2013). Suffering by comparison: Twitter users’ reactions to the Victoria’s secret fashion show. Body Image, 10, 648–652.

Claes, L., Müller, A., Norré, J., Assche, L., Wonderlich, S., & Mitchell, J. E. (2012). The relationship among compulsive buying, compulsive internet use and temperament in a sample of female patients with eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 20(2), 126–131. doi:10.1002/erv.1136.

Csipke, E., & Horne, O. (2007). Pro-eating disorder websites: Users’ opinions. European Eating Disorders Review, 15(3), 196–206. doi:10.1002/erv.789.

Custers, K., & Van den Bulck, J. (2009). Viewership of pro-anorexia websites in seventh, ninth and eleventh graders. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(3), 214–219. doi:10.1002/erv.910.

de Vries, D. A., & Peter, J. (2013). Women on display: The effect of portraying the self online on women’s self-objectification. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 1483–1489.

de Vries, D. A., Peter, J., Nikken, P., & de Graaf, H. (2014). The effect of social network site use on appearance investment and desire for cosmetic surgery among adolescent boys and girls. Sex Roles, 71(9–10), 283–295. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0412-6.

Delforterie, M. J., Larsen, J. K., Bardone-Cone, A. M., & Scholte, R. H. (2014). Effects of viewing a pro-ana website: An experimental study on body satisfaction, affect, and appearance self-efficacy. Eating Disorders, 22(4), 321–336. doi:10.1080/10640266.2014.898982.

Dijkstra, J. K., Cillessen, A. H., & Borch, C. (2013). Popularity and adolescent friendship networks: Selection and influence dynamics. Developmental Psychology, 49(7), 1242. doi:10.1037/a0030098.

Fahs, B., & Gohr, M. (2012). Superpatriarchy meets cyberfeminism: Facebook, online gaming, and the new social genocide. MP An Online Feminist Journal, 3(6), 1–40.

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). The mediating role of appearance comparisons in the relationship between media usage and self-objectification in young women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. doi:10.1177/0361684315581841.

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015b). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women’s body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002.

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12, 82–88. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004.

Fernandes, C. A., Rodgers, R. F., & Franko, D. L. (2013). “Yo/Eu Gorda? Nunca!” (Me, fat? Never!): An exploration of Latino and English appearance-related micro-aggressions on Twitter. Paper presented at the International Conference on Eating Disorders, Montreal, QC.

Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E. (2011). Social psychological theories of disordered eating in college women: Review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1224–1237. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.011.

Fox, J., & Rooney, M. C. (2015). The Dark Triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self-presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 161–165. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.017.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Frisén, A., Berne, S., & Lunde, C. (2014). Cybervictimization and body esteem: Experiences of Swedish children and adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 11(3), 331–343. doi:10.1080/17405629.2013.825604

Garandeau, C. F., Lee, I. A., & Salmivalli, C. (2014). Inequality matters: Classroom status hierarchy and adolescents’ bullying. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(7), 1123–1133. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-0040-4.

Gavin, J., Rodham, K., & Poyer, H. (2008). The presentation of “Pro-Anorexia” in online group interactions. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 325–333. doi:10.1177/1049732307311640.

Ghaznavi, J., & Taylor, L. D. (2015). Bones, body parts, and sex appeal: An analysis of# thinspiration images on popular social media. Body Image, 14, 54–61. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.03.006.

Gies, L. (2008). How material are cyberbodies? Broadband Internet and embodied subjectivity. Crime, Media, Culture, 4(3), 311–330. doi:10.1177/1741659008096369.

Gies, J., & Martino, S. (2014). Uncovering ED: A qualitative analysis of personal blogs managed by individuals with eating disorders. The Qualitative Report, 19(29), 1–15.

Giles, D. (2006). Constructing identities in cyberspace: The case of eating disorders. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45(3), 463–477. doi:10.1348/014466605x53596.

Greenfield, P. M. (2004). Developmental considerations for determining appropriate Internet use guidelines for children and adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(6), 751–762. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2004.09.008.

Greenfield, P., & Yan, Z. (2006). Children, adolescents, and the Internet: A new field of inquiry in developmental psychology. Developmental Psychology, 42(3), 391. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.391.

Haferkamp, N., & Krämer, N. C. (2011). Social comparison 2.0: Examining the effects of online profiles on social-networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14, 309–314. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0120.

Harper, K., Sperry, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2008). Viewership of pro-eating disorder websites: Association with body image and eating disturbances. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(1), 92–95. doi:10.1002/eat.20408.

Hayes, M., van Stolk-Cooke, K., & Muench, F. (2015). Understanding Facebook use and the psychological affects of use across generations. Computers in Human Behavior, 49, 507–511. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.040.

Hetzel-Riggin, M. D., & Pritchard, J. R. (2011). Predicting problematic internet use in men and women: The contributions of psychological distress, coping style, and body esteem. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 14(9), 519–525. doi:10.1089/cyber.2010.0314.

Hoff, D. L., & Mitchell, S. N. (2009). Cyberbullying: Causes, effects, and remedies. Journal of Educational Administration, 47, 652–665. doi:10.1108/09578230910981107.

Hummel, A. C., & Smith, A. R. (2015). Ask and you shall receive: Desire and receipt of feedback via Facebook predicts disordered eating concerns. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(4), 436–442. doi:10.1002/eat.22336.

Hussin, M., Frazier, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2011). Fat stigmatization on YouTube: A content analysis. Body Image, 8, 90–92. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.10.003.

Jaschinski, C., & Kommers, P. (2012). Does beauty matter? The role of friends’ attractiveness and gender on social attractiveness ratings of individuals on Facebook. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 8(3), 389–401. doi:10.1504/IJWBC.2012.048060.

Jett, S., LaPorte, D. J., & Wanchisn, J. (2010). Impact of exposure to pro-eating disorder websites on eating behaviour in college women. European Eating Disorders Review, 18(5), 410–416. doi:10.1002/erv.1009.

Jones, D. C., Vigfusdottir, T. H., & Lee, Y. (2004). Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys an examination of friend conversations, peer criticism, appearance magazines, and the internalization of appearance ideals. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19(3), 323–339. doi:10.1177/0743558403258847.

Juarez, L., Soto, E., & Pritchard, M. E. (2012). Drive for muscularity and drive for thinness: The impact of pro-anorexia websites. Eating Disorders, 20(2), 99–112. doi:10.1080/10640266.2012.653944.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2012). The Britney Spears universe: Social media and viral marketing at its best. Business Horizons, 55(1), 27–31. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2011.08.009.

Keery, H., Van den Berg, P., & Thompson, J. K. (2004). An evaluation of the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance with adolescent girls. Body Image, 1, 237–251. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.03.001.

Kichler, J. C., & Crowther, J. H. (2009). Young girls’ eating attitudes and body image dissatisfaction: Associations with communication and modeling. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 212–232. doi:10.1177/0272431608320121.

Kim, J. W., & Chock, T. M. (2015). Body image 2.0: Associations between social grooming on Facebook and body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 331–339. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.009.

Klump, K. L., Wonderlich, S., Lehoux, P., Lilenfeld, L. R., & Bulik, C. (2002). Does environment matter? A review of nonshared environment and eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31(2), 118–135. doi:10.1002/eat.10024.

Koronczai, B., Kökönyei, G., Urbán, R., Kun, B., Pápay, O., Nagygyörgy, K., et al. (2013). The mediating effect of self-esteem, depression and anxiety between satisfaction with body appearance and problematic internet use. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 39, 259–265. doi:10.3109/00952990.2013.803111.

Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2009). “Everybody knows that mass media are/are not [pick one] a cause of eating disorders”: A critical review of evidence for a causal link between media, negative body image, and disordered eating in females. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 9–42. doi:10.1521/jscp.2009.28.1.9.

Lloyd, B. T. N. (2002). A conceptual framework for examining adolescent identity, media influence, and social development. Review of General Psychology, 6(1), 73. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.1.73.

Mabe, A. G., Forney, K. J., & Keel, P. K. (2014). Do you “like” my photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(5), 516–523. doi:10.1002/eat.22254.

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Duggan, M., Cortesi, S., & Gasser, E. (2013). Teens and technology 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project.

Manago, A. M., Ward, L. M., Lemm, K. M., Reed, L., & Seabrook, R. (2015). Facebook involvement, objectified body consciousness, body shame, and sexual assertiveness in college women and men. Sex Roles, 72(1–2), 1–14. doi:10.1007/s11199-014-0441-1.

Marshall, P. D. (2010). The promotion and presentation of the self: Celebrity as marker of presentational media. Celebrity Studies, 1(1), 35–48. doi:10.1080/19392390903519057.

McKinley, N. M. J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181.

Meier, E. P., & Gray, J. (2014). Facebook photo activity associated with body image disturbance in adolescent girls. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(4), 199–206. doi:10.1089/cyber.2013.030.

Melioli, T., Rodgers, R. F., Rodrigues, M., & Chabrol, H. (2015). The role of body image in the relationship between Internet use and bulimic symptoms: Three theoretical frameworks. Cyber Psychology, Behavior, & Social Networking (in press).

Menzel, J. E., Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Mayhew, L. L., Brannick, M. T., & Thompson, J. K. (2010). Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 7(4), 261–270. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.05.004.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y.-P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377–398. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Mulveen, R., & Hepworth, J. (2006). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of participation in a pro-anorexia Internet site and its relationship with disordered eating. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(2), 283–296. doi:10.1177/1359105306061187.

Musaiger, A. O., & Al-Mannai, M. (2013). Role of obesity and media in body weight concern among female university students in Kuwait. Eating Behaviors, 14(2), 229–232. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.12.004.

Oates, C., Blades, M., & Gunter, B. (2002). Children and television advertising: When do they understand persuasive intent? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1(3), 238–245. doi:10.1002/cb.69.

Pea, R., Nass, C., Meheula, L., Rance, M., Kumar, A., Bamford, H., et al. (2012). Media use, face-to-face communication, media multitasking, and social well-being among 8-to 12-year-old girls. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 327. doi:10.1037/a0027030.

Peat, C. M., Von Holle, A., Watson, H., Huang, L., Thornton, L. M., Zhang, B., et al. (2014). The association between internet and television access and disordered eating in a Chinese sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders,. doi:10.1002/eat.22359.

Peebles, R., Wilson, J. L., Litt, I. F., Hardy, K. K., Lock, J. D., Mann, J. R., & Borzekowski, D. L. G. (2012). Disordered eating in a digital age: Eating behaviors, health, and quality of life in users of websites with pro-eating disorder content. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(5), e148. doi:10.2196/jmir.2023.

Pempek, T. A., Yermolayeva, Y. A., & Calvert, S. L. (2009). College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(3), 227–238. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.010.

Peña, J., & Brody, N. (2014). Intentions to hide and unfriend Facebook connections based on perceptions of sender attractiveness and status updates. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 143–150.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2014). Does exposure to sexually explicit Internet material increase body dissatisfaction? A longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 297–307. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.071.