Abstract

Institutional investors are increasingly pushing their investee companies to address environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues—a phenomenon commonly called ESG stewardship. Scholars have put forward various reasons for investors’ enthusiasm for ESG stewardship. They include the financial materiality of ESG issues, a desire to appeal to ESG-conscious customers, and the scope for fund operators to charge higher fees for funds that pursue ESG strategies. There is, however, another critical factor at play. ESG stewardship is also underpinned by a transnational development—what this article calls the ‘global ESG stewardship ecosystem’. This global ecosystem is comprised of various ESG-focused actors, including United Nations agencies, institutional investors, investor networks, service providers to institutional investors, and NGOs and activist organizations. These actors operate in a highly networked manner at the transnational level to develop and disseminate norms of ESG stewardship throughout global markets, and encourage and coordinate investors’ ESG stewardship activities on the ground. This article highlights the scale, complexity and influence of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem, revealing it to be a significant facilitator of institutional investors’ ESG stewardship. This insight calls into question important contemporary assumptions and theories about institutional investors, including claims that they are ‘rationally reticent’, under-invest in corporate governance activities, and are incapable of overcoming collective action challenges. The global ESG stewardship ecosystem is also a remarkable example of the transnational influences shaping contemporary corporate governance. The ecosystem underpins the development and dissemination of norms of ESG stewardship and also assists institutional investors to undertake ESG stewardship ‘on the ground’ in the various markets in which they operate. The transnational influence of the ecosystem has important implications for national law makers and regulators who are focused on ESG investing and investor participation in public company corporate governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the fields of corporate governance and regulation, there is growing interest in the phenomenon of international or transnational corporate law,Footnote 1 which involves the creation and transmission of corporate governance laws and norms at a supranational level.Footnote 2 Scholars have highlighted the increasing significance of transnational corporate law and corporate governance rules,Footnote 3 as well as their complexity.Footnote 4 This complexity, which is a key characteristic of transnational law generally,Footnote 5 involves multi-directional processes of law development and transmission resulting from the initiatives of numerous state, international and private actors.Footnote 6

Transnational developments are driving a striking contemporary corporate governance practice: ESG stewardship. ‘ESG stewardship’ refers to investors using their influence as major shareholders to prompt public companies to address material environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) issues such as climate change.Footnote 7 Recent years have witnessed a ‘remarkable’Footnote 8 rise of ESG stewardship across various global markets.Footnote 9 In the United States, commentators have described this development as ‘a true paradigm shift in the relationships between public companies and their investors’.Footnote 10 ESG stewardship’s growing significance in the United States is also reflected in the critical attention it has received from Republican law makers and officials, who regard it as an inappropriate exercise in progressive politics and are taking steps to inhibit or penalize investors’ attempts to undertake ESG stewardship.Footnote 11

This corporate governance phenomenon is underpinned by what this article calls the ‘global ESG stewardship ecosystem’. This ecosystem is a transnational network of different non-state actors, including globally active institutional investors, international institutions and agencies, non-governmental organizations, investor networks and representative bodies, as well as the various service providers that support the governance activities of institutional investors.

This ecosystem exerts significant influence over ESG stewardship. It shapes institutional investors’ ESG stewardship both ‘on the books’ through its development and dissemination of norms of ESG stewardship, and ‘on the ground’ by facilitating and coordinating investors’ ESG stewardship activities. The ecosystem’s reach is global, with the result that ESG stewardship now targets public companies in markets around the world, including developing markets.Footnote 12

Our article analyzes and explores the global ESG stewardship ecosystem and its complex web of institutional investors and other actors. In doing so, the article makes three important contributions. First, it highlights the ecosystem’s scale and its influence in public company governance. Second, our original account of the ESG stewardship ecosystem challenges and calls into question claims about the limited capacity and incentives of institutional investors to engage in corporate governance activities.Footnote 13 It has been argued, for example, that institutional investors are ‘rationally reticent’ and require the intervention of more proactive actors, such as activist hedge funds, to spur their involvement in public company governance.Footnote 14 The activities of the ESG ecosystem suggest otherwise. Our article reveals how institutional investors play a leading role in the ecosystem, including by developing and disseminating ESG stewardship norms and practices and undertaking ESG stewardship ‘on the ground’. Much of this activity is undertaken collaboratively, leveraging the collective influence, know-how and experience of the ecosystem’s constituents. Our novel account of institutional investors’ proactive, collective and transnational behavior in the ESG stewardship ecosystem has important implications for contemporary debates in corporate governance scholarship, including in relation to investors’ capacity to engage meaningfully in corporate governance;Footnote 15 ‘systematic’ stewardship by highly diversified investors;Footnote 16 and the relevance and impact of institutional investor stewardship codes.Footnote 17

Finally, the article argues that the coordinated and transnational nature of the ecosystem’s activities creates the prospect of greater convergence and harmonization in ESG stewardship norms and practices across global markets.Footnote 18 This involves both opportunities and risks for corporate and financial regulation. On the one hand, the ecosystem may provide momentum for national initiatives to promote investor stewardship and sustainable finance. On the other hand, tension may arise where the goals, norms, and practices promoted by the ecosystem are inconsistent with the expectations of national law makers and regulators. Moreover, the variety of organizations in the ecosystem, any number of which may be sensitive to local interest group or political pressure, creates the possibility of regional or national variations in ESG stewardship norms and practices. This raises the very real possibility of what Gordon has described as ‘divergence within convergence’.Footnote 19 These insights have relevance for national law makers and regulators who are exploring regulatory strategies for encouraging investor participation in corporate governance and sustainable finance or, as the case may be, for constraining what they perceive to be a form of ‘woke capitalism’.

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 explores what is meant by ‘ESG stewardship’, why investors undertake it, and its increasing significance in practice. Section 3 highlights and examines the global ESG stewardship ecosystem—the substantial transnational phenomenon which this article argues is underpinning investors’ ESG stewardship. Section 4 considers the implications of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem for important contemporary corporate governance debates and developments, and Sect. 5 concludes.

2 ESG Stewardship

2.1 What Is ESG Stewardship?

Investors commonly use the acronym ESG adjectivally to describe a particular investment approach; namely, an approach that is guided by a broader conception of the considerations that are material to investment decision-making.Footnote 20 This broader conception is delineated by the ‘E’, ‘S’ and ‘G’ categories in the acronym ESG. ‘E’, ‘S’ and ‘G’ refer, respectively, to environmental issues, societal issues, and corporate governance practices and arrangements.Footnote 21 The boundaries of the ‘E’, ‘S’ and ‘G’ categories are, in practice, drawn broadly and encompass a wide range of salient issues, ranging from mitigation of climate change risk, respect for human rights, achieving board and workforce diversity, and executive remuneration practices.Footnote 22

Precisely how investors use ESG considerations in their investment activities varies. Many investors use them to guide capital allocation and trading decisions; for example, impact, divestment and screening investment strategies.Footnote 23 However, investors are also increasingly using ESG considerations to define the objectives and nature of their governance interactions with their investee companies.Footnote 24 For example, an investor which is concerned about a portfolio company’s preparedness for the transition to a low-carbon economy may pressure that company to hasten its adaptation through private discussions and/or voting in favor of shareholder proposals.Footnote 25 Highly diversified investors are engaging with multiple companies across an entire sector on the same ESG issues where they consider that such issues have sector-wide (or even economy-wide) significance.Footnote 26

The term ‘stewardship’ is now a common way of describing this type of investor-company engagement.Footnote 27 The term has acquired a degree of formality in the various jurisdictions that have adopted institutional investor stewardship codes—typically ‘soft law’ codes of conduct that exhort institutional investors to engage meaningfully with their investee companies with a view to encouraging sustainable corporate activity and investment returns. These codes typically envisage stewardship as encompassing meaningful recurring interactions between investors and investee companies, including through informed share voting and private communications.Footnote 28 Many stewardship codes also press investors to take escalatory action if companies do not address their concerns, such as by voting against the re-election of directors, although codes can vary in their emphasis on both the need for and methods of escalation.Footnote 29

Even in the United States, where critics have expressed doubts about the efficacy of stewardship codes as a mechanism for prompting institutional investors to play a proactive corporate governance role,Footnote 30 the term ‘stewardship’ has entered common parlance as a way of describing the interactions between investors and their investee companies.Footnote 31

2.2 ESG Stewardship in Action

ESG stewardship involves shareholders proactively engaging with their investee companies to address ESG issues. It therefore involves shareholders adopting an ‘activist’ stance; that is, taking action to influence change in their companies’ affairs in relation to ESG issues.

US academic literature has paid much attention to the role played by activist hedge funds as a catalyst for shareholder activism.Footnote 32 A classic example of this paradigm in the ESG context is the well-known activist campaign at ExxonMobil in the United States. In late 2020, a small hedge fund, Engine No. 1 LLC (Engine No. 1), nominated four new directors to ExxonMobil’s board of directors with the aim of ‘purposefully repositioning [the] company to succeed in a decarbonizing world’.Footnote 33 In spite of opposition from ExxonMobil’s management,Footnote 34 three of the nominees were elected.Footnote 35 Engine No. 1 was the clear leader in this offensive. However, the campaign’s success was due to the fact that BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, which collectively owned more than 20% of ExxonMobil’s stock,Footnote 36 ultimately supported the hedge fund which owned a mere 0.02% stake.Footnote 37 The institutional investors’ power in this regard has led to their description as ‘kingmakers’.Footnote 38

Hedge funds have also engaged in ESG stewardship in other jurisdictions. For example, in 2020, Sir Chris Hohn’s hedge fund, The Children’s Investment Fund Management (TCI), and its charitable foundation, The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), launched the so-called Say on Climate project, an annual voting initiative which is designed to prompt companies to inform shareholders about how they plan to manage greenhouse gas emissions in accordance with the Paris Agreement.Footnote 39

The Say on Climate project has gone global. TCI announced plans to file resolutions requesting annual shareholder ‘say on climate’ votes at 100 companies in the S&P 500 index by the end of 2022,Footnote 40 and several US issuers, including S&P Global and Moody’s, have publicly supported the initiative.Footnote 41 In the Asia-Pacific region, the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) joined with CIFF to file ‘say on climate’ resolutions at a number of Australian resource companies.Footnote 42 CIFF announced that it is also working with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), asset owners and asset managers to file ‘say on climate’ resolutions in Asia.Footnote 43

In spite of these examples, the hedge fund activism paradigm in US academic literature is not representative of most contemporary ESG stewardship. Much ESG stewardship is instead undertaken by mainstream institutional investors. The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance reports, for example, that ‘corporate engagement and shareholder action’ directed at ESG issues—which it defines as ‘[e]mploying shareholder power to influence corporate behavior’Footnote 44—has experienced consistent growth worldwide since 2016 as an investment strategy and, in 2020, was the third most common sustainable investment strategy (as measured by assets under management).Footnote 45

Indeed, in recent years it has become common for major international investment managers to proclaim their commitment to ESG stewardship. BlackRock, for instance, reported a 48% increase in engagements directed at ESG issues between 2019 and 2020.Footnote 46 Investors have also harnessed their voting power to pressure their investee companies to address ESG concerns.Footnote 47 Aberdeen Standard, for example, reported that in 2020 it took ‘voting action against 38 companies in the UK, 60 in the US, 4 in Canada, 5 in Switzerland and 3 in other European markets’ owing to concerns about board gender diversity.Footnote 48 Academic research has also highlighted the scope of investors’ ESG stewardship in various markets across the globe.Footnote 49

Commentators have heralded investors’ growing propensity for ESG stewardship as a ‘paradigm shift’ in public company governanceFootnote 50 and ‘a very powerful driver towards a more sustainability-oriented future in corporate governance’.Footnote 51

A range of factors lie behind investors’ increasing engagement in ESG stewardship. First, many investors regard ESG considerations as directly material to how they make and manage their investments. It is helpful to think of investors’ conception of this materiality as comprising a spectrum of views ranging from an approach at one end that takes account of ESG factors exclusively for their impact on the risk-adjusted return of an investment and an approach at the other end that takes account of ESG factors for non-financial reasons (such as ethical or faith-based considerations).Footnote 52 Commentary indicates that, in practice, a substantial majority of investors lie towards the value-based end of this spectrum, focusing on ESG considerations exclusively or mainly for their potential financial relevance.Footnote 53 For example, an investor may critically examine how an oil and gas company is adapting its business model to address climate change transition risks because a failure by the company to do so may result in an unsustainable business model that negatively affects the investor’s returns. Highly diversified institutional investors, in particular, may have strong incentives to pressure companies to address ESG issues that could have an economy-wide (or systemic) impact, such as climate change and social inequality. This is because the highly diversified nature of their investments means that these investors effectively ‘own the market’ and cannot, therefore, avoid the potential economy-wide impact of such issues.Footnote 54 Focusing on ESG factors because of their financial materiality has been described as the mainstream approach to ESG investing.Footnote 55

Second, regulatory and quasi-regulatory developments are also prompting a focus on ESG investing and stewardship.Footnote 56 The European Union, for example, has been particularly active in developing regulation in relation to investor stewardship and sustainable finance. The amended Shareholder Rights Directive contains a clear expectation that institutional investors will engage with their investee companies.Footnote 57 The EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive, Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation and Taxonomy Regulation also contain detailed requirements, which seek to promote sustainable economic activity and provide transparency regarding the approach of companies and investors toward sustainability issues.Footnote 58

Investor stewardship codes constitute another important development in this area. The United Kingdom’s Financial Reporting Council issued the original stewardship code in 2010 as a response to concerns that, during the Global Financial Crisis, institutional investors had exercised inadequate oversight of excessive risk taking by banks and other financial institutions.Footnote 59 The UK code exhorted institutional investors to monitor their investee companies, to develop a policy on when and how they would escalate unresolved concerns regarding their investee companies, and to act collectively with other shareholders to address such concerns.Footnote 60

Stewardship codes have proliferated since 2010 and now exist in at least 20 jurisdictions.Footnote 61 Some codes go a step further and actively promote ESG stewardship.Footnote 62 One of the Australian stewardship codes notes, for example, that

[s]tewardship refers to the responsibility asset owners have to exercise their ownership rights to protect and enhance long-term investment value for their beneficiaries … One way that asset owners can help protect and enhance their investments for the long term is by considering ESG matters through their stewardship practices.Footnote 63

Recent revisions to the UK, Japanese and Singaporean stewardship codes have also placed far greater weight on ESG considerations.Footnote 64

Finally, commentators have identified a variety of other commercial, political and social factors that are contributing to investors’ growing focus on ESG stewardship. It has been pointed out, for example, that operating ESG-focused funds can be financially attractive for fund managers.Footnote 65 US researchers claim that US index funds emphasize their commitment to ESG stewardship as a way of attracting business from millennial investors and to recruit and retain millennial employees.Footnote 66 The threat of further regulatory initiatives may also indirectly affect investor behavior. Davies, for example, has argued that investors in the United Kingdom have material incentives to demonstrate a commitment to ESG stewardship in order to forestall prescriptive government regulation in this area.Footnote 67

However, the growing significance of ESG stewardship across the globe is not simply the confluence of separate national trends shaped by local regulatory, political, social, commercial and financial factors. There is also an important transnational dimension to the increasing global significance of ESG stewardship: what this article calls the global ESG stewardship ecosystem.

3 Introducing the Global ESG Stewardship Ecosystem

The global ESG stewardship ecosystem is a transnational ecosystem of diverse non-state actors which provides both normative and practical support for the global dissemination of ESG stewardship. This article argues that the existence, scale and activities of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem have significant implications for our understanding of the potential and the regulatory implications of ESG stewardship and the role of institutional investors in corporate governance. This section outlines the key elements and moving parts of this global ecosystem.

3.1 International Agencies as Transnational ESG Stewardship Norm Creators and Stewardship Promoters

One point that quickly emerges from an examination of the recent growth of ESG stewardship is the significant role of international agencies in developing ESG stewardship norms and practices. This multiplicity of global standard-setters, which often act collectively, has been described as creating a ‘veritable alphabet soup of acronyms’.Footnote 68

The United Nations (UN) and its agencies have been at the forefront of ESG norm creation and dispersion.Footnote 69 In February 1999, then-Secretary General Kofi Annan proposed that the UN and business leaders establish a ‘global compact of shared values and principles, which will give a human face to the global market’.Footnote 70 Officially launched in July 2000,Footnote 71 the Global Compact describes itself as ‘the world’s largest corporate sustainability initiative’.Footnote 72 Through this initiative, the UN has strategically sought to involve the private sector in advancing human rights and global sustainability, as well as mobilizing ‘a global movement of sustainable companies and stakeholders’.Footnote 73 The Global Compact now has nearly 20,000 participating organizations that, as a condition of membership, pledge to operate responsibly, promote sustainability and report annually on their efforts.Footnote 74

In implementing the Global Compact, the UN and its agencies have focused in particular on the investment community, with a view to leveraging the capital markets to drive private sector changes.Footnote 75 In 2004, the Global Compact published a report entitled ‘Who Cares Wins: Connecting Financial Markets to a Changing World’, which first coined the ‘environmental, social and governance’ epithet and acronym.Footnote 76 The aim of this report was to improve the investment community’s understanding of ESG risks and opportunities and promote greater integration of ESG considerations in investment decisions.Footnote 77 The report’s central message was that ESG factors have real economic consequences and can, therefore, have a material impact on a firm’s financial performance and its valuation.Footnote 78

Another key UN initiative in this area was the 2006 launch at the New York Stock Exchange of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), which considers itself ‘the world’s leading proponent of responsible investment’.Footnote 79 The PRI published a set of six Principles for Responsible Investment (Principles),Footnote 80 which include a call for its signatories to incorporate ESG considerations into their investment analysis and decision-making and to engage actively with their investee companies regarding such considerations.Footnote 81 The PRI’s strategic plan seeks, inter alia, to ‘[f]oster a community of active owners’ and ‘[c]hampion climate action’.Footnote 82

The number of PRI signatories has grown from 100 at the time of its launch to more than 5000 institutional investors and allied organizations representing in excess of US$120 trillion in assets under management.Footnote 83 Some of the largest yearly increases in signatories have occurred since 2018.Footnote 84 In recent years, the PRI has directed resources and attention to ensuring greater accountability of signatories for failure to implement the Principles and for greenwashing.Footnote 85 New accountability mechanisms include development of a watch list for non-compliant signatories, with the potential for delisting if they fail to meet minimum criteria after 2 years.Footnote 86

The UN and the PRI have, in turn, helped to establish several climate change-focused collaborative initiatives with the investment sector. In 2019, the UN and PRI established the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance (Owner Alliance), which is supported by two prominent NGOs, the Worldwide Fund for Nature and Global Optimism.Footnote 87 Membership of the Owner Alliance comprises more than 60 institutional investors with over US$10 trillion assets under management.Footnote 88 These members have committed to achieving net-zero emissions in their investment portfolios by 2050, using a range of measures including company engagement.Footnote 89

In 2020, the PRI also co-founded a parallel initiative targeting asset managers. The Net Zero Asset Managers Alliance (Managers Alliance) has more than 300 signatories, managing in excess of US$64 trillion of assets.Footnote 90 These signatories are committed to supporting investment strategies that are aligned with a goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 or sooner.Footnote 91 Membership of the Managers Alliance has implications for ESG activism. By becoming members, signatories commit to implementing ‘a stewardship and engagement strategy, with a clear escalation and voting policy, that is consistent with the [Managers Alliance’s] ambition’.Footnote 92 Both the Owner Alliance and the Managers Alliance are members of the Race to Zero network, which was formed under the auspices of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Race to Zero network’s primary goal is to mobilize non-state actors into promoting efforts towards a decarbonized world economy.Footnote 93

Another supranational program designed to address climate change is The Investor Agenda. This program, founded by the PRI, the UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP Finance Initiative) and five investor networks,Footnote 94 describes itself as ‘a common leadership agenda … focused on accelerating investor action for a net-zero emissions economy’.Footnote 95 One of The Investor Agenda’s core objectives is to prompt investors to engage with, and put pressure on, companies to ‘accelerat[e] the business transition to a net-zero carbon economy’ and ‘drive the boards and senior management … to take action to reduce GHG emissions across the value chain’.Footnote 96 To this end, it encourages investors to support one of three investor-driven initiatives designed to prompt public companies to respond to the risks of climate change.Footnote 97 The Investor Agenda also includes prominent NGO organizations, such as ShareAction and the Interfaith Centre on Corporate Accountability, as ‘supporting partners’.Footnote 98

To foster investors’ pursuit of ESG-related objectives, UN agencies have emphasized that responsible investment practices, such as ESG stewardship, are permitted, and perhaps required, by existing laws.Footnote 99 In 2005, the UNEP Finance Initiative commissioned a report from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer (Freshfields Report) on this topic.Footnote 100 A decade later, the PRI, the UNEP Finance Initiative and the Generation Foundation launched a four-year project, entitled ‘Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century’.Footnote 101 The group published a preliminary report in 2015,Footnote 102 a Global Statement on Investor Obligations and Duties the following yearFootnote 103 and a Final Report in 2019 (2019 Final Report).Footnote 104 The overall project was prompted by the apparent belief of some institutional investors that consideration of ESG factors was inconsistent with their fiduciary duties.Footnote 105 An ancillary issue was whether ‘active ownership and public policy engagement’ accorded with investors’ fiduciary duties.Footnote 106

The Freshfields Report, together with the various statements and reports associated with the Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century project, concluded that institutional investors are required to have regard to ESG considerations in their decision-making. The foreword to the Freshfields Report, for example, states that the Report’s findings should help dispel the ‘all-too-common misunderstanding’ that fiduciary responsibility is restricted to profit maximization.Footnote 107 The 2015 Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century report states that ‘failing to consider long-term investment value drivers, which include environmental, social and governance issues, in investment practice is a failure of fiduciary duty’.Footnote 108 According to the 2019 Final Report, the reason for this is that ESG factors are ‘financially material’ and failure to identify and consider them can result in mispricing of risk and sub-optimal decisions regarding asset allocation.Footnote 109

A handful of other international and supranational bodies play a role in the development and dissemination of ESG stewardship norms and practices. For example, the World Economic Forum established an Active Investor Stewardship Project to promote investor stewardshipFootnote 110 and an initiative comprising institutional investors and other financial sector organizations to promote stakeholder capitalism through coordinated action between multiple stakeholders.Footnote 111 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has published guidance to assist institutional investors implement due diligence practices to address human rights, environmental, labor rights and corruption issues in their investment portfolios.Footnote 112 Actions recommended by the OECD guidance include active engagement by institutional investors with their portfolio companies, together with ‘participation in industry or multi-stakeholder initiatives … (e.g. PRI Collaboration Platform, UNEP Finance Initiative, Investor networks on climate change, Corporate Sustainability Reporting Coalition)’.Footnote 113

In summary, a raft of international agencies today plays a key role in developing norms of ESG stewardship, including a clear expectation that investors will engage proactively with companies on ESG issues, and works closely with institutional investors and other organizations to encourage the dissemination and implementation of these norms.

3.2 Cross-Border Activities of Institutional Investors

As just noted, institutional investors play an important role in the international development, dissemination and implementation of ESG stewardship norms and practices.

Prominent institutional investors now routinely proclaim the international scope of their ESG stewardship. For example, Legal & General Investment Management, one of Europe’s largest asset managers, reported that in 2019 it engaged companies with low levels of gender diversity throughout the world, including in the US, Japan, Asia Pacific and emerging markets.Footnote 114 BlackRock’s 2020 and 2021 global stewardship reports provide examples of engagement in Asia, Europe, and Latin America.Footnote 115 European institutional investors have also demonstrated an increasing focus on ESG issues in Asia.Footnote 116

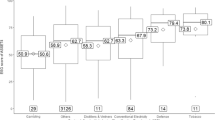

There is some evidence that the majority of such globally active investors hail from a handful of western markets. Dimson et al. report, for example, that more than half of the shareholders participating in coalitions coordinated through the global Collaboration Platform of the PRI were from just four countries.Footnote 117

The contribution of such globally active investors to local market ESG stewardship is multi-dimensional. In some cases, these investors effectively operate as ‘importers’ of ESG stewardship norms and practices. The Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, for instance, has acknowledged its role as a norm-importer in emerging markets where it operates. The Pension Board has noted that, although it needs to make some allowance in emerging markets for ‘normative differences’ regarding ESG considerations, it nonetheless adopts certain non-negotiable ‘baseline’ expectations. One such expectation is that investee companies in emerging markets take adequate action to manage climate change risk.Footnote 118

In other cases, globally active investors act as supporters rather than leaders, lending their investment heft and experience to support the initiatives of local investors, thereby creating a distinctive form of transnational ‘agency capitalism’.Footnote 119 Dimson et al. note, for example, how coalitions coordinated under the PRI’s Collaboration Platform commonly comprise a mixture of domestic and offshore investors, with the former often acting as lead investors and the latter as supporting investors.Footnote 120 A similar pattern can be seen in the Asian working group convened by Climate Action 100+, where one of the key objectives is to partner Asian investors with international investors in order to combine Asian investors’ local knowledge and cultural familiarity with international investors’ significant offshore engagement experience.Footnote 121

A 2020 shareholder campaign against Rio Tinto, one of the world’s largest mining companies which has a dual listing on the London and Australian stock exchanges, provides a notable case study of the multi-directional interactions between globally active and local investors that underpin ESG stewardship.Footnote 122

The background to the activist campaign against Rio Tinto is as follows. In late May 2020, Rio Tinto conducted a blasting operation at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia to gain access to a high-quality iron ore deposit.Footnote 123 Although the blasting was legislatively authorizedFootnote 124 and therefore legal, it destroyed two rock shelters, which were 46,000 year old Aboriginal cultural heritage sites.Footnote 125 The destruction was said to have caused ‘indescribable’ griefFootnote 126 for the traditional owners of the land, the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura peoples.Footnote 127

News of the blasting resulted in public outrageFootnote 128 and the launch of a government inquiry.Footnote 129 It also prompted an announcement by Rio Tinto in June 2020 that the board of directors would conduct a review of the company’s heritage management processes,Footnote 130 with a view to recommending procedural improvements.Footnote 131 The board’s report was published in August 2020.Footnote 132 Although the report identified serious deficiencies in the company’s processes and work culture,Footnote 133 the only penalty recommended was a £4 million reduction in executive pay for Rio Tinto’s then-CEO Jean-Sébastien Jacques and two other senior managers.Footnote 134

The report triggered an immediate negative response by some of Australia’s substantial industry pension (superannuation) funds,Footnote 135 and their representative organization, the Australian Council of Superannuation Investors (ACSI).Footnote 136 UniSuper and AustralianSuper, which were material shareholders in Rio Tinto, declared that the financial penalties were inadequate and failed to produce meaningful accountability.Footnote 137 ACSI adopted a similar position, stating that ‘[r]emuneration appears to be the only sanction applied to executives. This raises the question: does the company feel that £4 million is the right price for the destruction of cultural heritage?’Footnote 138

Yet, the ire of the Australian superannuation funds, which collectively held 20% of Rio Tinto stock, was not initially shared by US, UK and European investors, which owned a much larger proportion of Rio Tinto’s shares.Footnote 139 Indeed, it was reported that US investors were angry, not because they regarded Rio Tinto’s remuneration cuts as an inadequate penalty, but rather because they viewed them as overkill.Footnote 140

By early September 2020, this picture was changing, with reported ‘disquiet’ among some Rio Tinto board membersFootnote 141 and growing support for the stance of the Australian institutions coming from some international investors, such as the UK-based Local Authority Pension Fund (LAPFF) and the UK Church of England Pension Fund.Footnote 142 Aberdeen Standard Investments, one of the largest holders of Rio Tinto’s London-listed stock, also publicly announced that the destruction of the Juukan rock shelters called into question Rio Tinto’s commitment ‘to doing what is right, not just what is legal’.Footnote 143

A group of eleven institutional investors, acting collectively, wrote to Rio Tinto’s chairman urging the board to take stronger action.Footnote 144 Rio Tinto responded by announcing, on 11 September 2020, that its CEO and the two other executives would leave the company.Footnote 145 At the company’s annual shareholder meeting in London the following month, influential shareholders, including Norway’s oil fund and the LAPFF, voted against Rio Tinto’s remuneration report, which disclosed a pay rise for Jean-Sébastien Jacques in spite of the events at Juukan Gorge.Footnote 146

Local and international institutional investors have used the Juukan Gorge destruction to place pressure, not only on Rio Tinto, but also on other global mining companies.Footnote 147 In late October 2020, 64 institutional investors, representing over US$10.2 trillion, became signatories to a letter sent by ACSI and the UK Church of England Pension Fund, to major Australian and international mining companies.Footnote 148 The consortium of additional signatories was truly global in nature, comprising 12 Australian institutions; 34 UK institutions; 9 European institutions; 6 US institutions; one institution based in Canada and another in Chile.Footnote 149 Their letter, which was a clear shot across the bow, sought assurances from some of the world’s largest mining companies as to ‘how the sector obtains and maintains its social license to operate with First Nations and Indigenous peoples’.Footnote 150 The letter stressed that incidents such as the Juukan Gorge blasting pose a serious investment risk,Footnote 151 noting that, although this particular incident occurred in Australia, ‘the principles apply to projects across the world’.Footnote 152

The destruction of the Juukan Gorge has been described as a ‘potent global symbol’ of the growing importance of ESG investment.Footnote 153 As a case study, the Juukan Gorge incident highlights the intricate, networked nature of ESG stewardship. It shows that local and international institutional investors can build relationships and become repeat players in relation to ESG stewardship. For example, this was not the first time that the UK Church of England Pension Fund had collaborated with Australian superannuation funds to put ESG pressure on Rio Tinto.Footnote 154 The Juukan Gorge case study also highlights how institutional investors undertake their ESG stewardship collectively, and how larger, globally focused institutions play a pivotal role in such collective initiatives.

3.3 Investor Associations and Networks as Transnational Norm Developers and ESG Stewardship Facilitators

The Juukan Gorge case study is an example of international and local investors forming an ad hoc coalition to respond to a significant ESG concern. However, spontaneous formations of investor coalitions are not the only means by which institutional investors leverage their ESG stewardship. Investors are also increasingly exerting collective influence through representative bodies and formal investor networks,Footnote 155 a number of which operate across national borders and play a significant part in the global ESG stewardship ecosystem.

Some of these transnational investor associations and networks develop and promote stewardship norms and best practice behaviors.Footnote 156 Examples include the International Corporate Governance Network (ICGN)Footnote 157 and the European Fund and Asset Management Association (EFAMA).Footnote 158 Both organizations have published model stewardship codes that reference ESG considerations.Footnote 159 The preamble to the ICGN Code claims that stewardship involves ‘[c]onsideration of wider ethical, environmental and social factors as core components of [investors’] fiduciary duty’,Footnote 160 and Principle 6 of the Code states that investors should incorporate ESG factors into their stewardship activities.Footnote 161 The EFAMA Code defines stewardship as ‘engagement’ and notes that ‘[e]ngagement can be on matters such as … environmental and social concerns; corporate governance issues’.Footnote 162 Principle 1 requires that investors publish an engagement policy which should disclose how investee companies are monitored in relation to, among other things, ‘[e]nvironmental and social concerns’.Footnote 163

Recent research reveals the international influence of the ICGN and EFAMA model codes. Using a detailed textual analysis and cross-referencing methodology, Katelouzou and Siems highlight the influence of the ICGN Code on codes adopted in Malaysia and Kenya and the influence of the EFAMA Code on Italian stewardship codes.Footnote 164

Several other transnational investor networks assist institutional investors in their efforts to implement ESG stewardship ‘on the ground’. These networks do so by providing guidance and facilitating collective action by investors in relation to particular ESG issues. Examples of these networks include Climate Action 100+ (CA100+) (focused on climate change),Footnote 165 Investors Against Slavery and Trafficking APAC (focused on slavery and human trafficking in the Asia Pacific region)Footnote 166 and the PRI’s Collaboration Platform (which pursues a range of sustainability-related issues).Footnote 167 These networks cooperate with their investor members to settle agreed strategy and objectives in relation to their ESG focus areas, identify companies to target for intervention, and form coalitions of interested members to undertake the interventions.Footnote 168 Interventions can take a variety of forms, only some of which are visible.Footnote 169 Behind-the-scenes engagement can, for example, involve letter writing (as in the Juukan Gorge case study) or private meetings. Public interventions include voting against directors or filing a shareholder proposal at shareholder meetings.Footnote 170

These investor networks have global strategies and utilize evolved organizational structures to achieve transnational reach and influence. ICGN, for example, has an explicitly stated strategy of promoting good corporate governance and responsible investing stewardship globallyFootnote 171 and, as part of this mission, has coordinated global networks of investor associations and stewardship code issuers.Footnote 172

CA100+ also exemplifies the trend toward global collaboration. This investor network aims to leverage the shareholding power of institutional investors to compel the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters to address the climate change implications of their businesses.Footnote 173 The network brings together five separate investor networks, each of which has a particular geographical focus, to implement CA100+’s strategies. These networks are the Ceres Investor Network on Climate Risk and Sustainability (North American focus), the Asia Investor Group on Climate Change (Asian focus), the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (European focus) and the Investor Group on Climate Change (Australian and New Zealand focus).Footnote 174 A fifth network—the PRI—has a global focus.Footnote 175

CA100+ has a steering committee, comprising investor representatives, which maintains a ‘focus list’ of companies of concern and formulates broad strategic priorities for engaging with those companies.Footnote 176 Each network assists in assembling and coordinating coalitions of institutional investors to engage with targeted ‘focus list’ companies located in the network’s respective region.Footnote 177 The networks also help to develop and disseminate relevant know-how and assistance.Footnote 178 For example, State Street Global Advisors has adopted the influential Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) decarbonization framework as a guide to achieving net-zero investment portfolio decarbonization.Footnote 179

Similar transnational coordination can be seen in networks that are focused on other aspects of ESG. Investors Against Slavery and Trafficking APAC, for example, receives administrative and know-how support from three other ESG-focused organizations: the Liechtenstein Initiative for Finance Against Slavery and Trafficking; the Australian NGO, Walk Free; and the Find It, Fix It, Prevent It project run by CCLA Investment Management (which is based in the UK and manages investments for charities, religious organizations and the public sector).Footnote 180 The CCLA Investment Management project is, in turn, supported by the PRI.Footnote 181

These various networks claim significant investor support. CA100+, for example, states that it has more than 700 investors across 33 markets with over US$68 trillion of assets under management.Footnote 182 Survey data from North America and Australasia reveals that a significant proportion of institutional investors in those regions participate in at least one such network.Footnote 183

3.4 Internationally Active Advocacy Organizations

Internationally active public advocacy organizations also play a role in the global ESG stewardship ecosystem.Footnote 184 These are non-commercial organizations which engage in activism in relation to environmental or social issues. Some of these organizations, such as ShareAction and Shareholder Commons, engage in international collaborations as part of their campaigns to compel major public companies to address environmental or social concerns and work closely with institutional investors to achieve their aims.

For example, ShareAction coordinates three investor coalitions comprised of institutional investors from around the globe relating to climate change, improving children’s health and improving workplace safety.Footnote 185 ShareAction has also partnered with the Australia-based advocacy organization, the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility, the Carbon Disclosure Project and the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, to promote the introduction of ‘say on climate’ votes at companies across the globe.Footnote 186 Shareholder Commons has partnered with Jesus College, Cambridge, and the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge to work with investors to encourage proxy advisers to take into account the systemic effects of corporate behavior when providing proxy advice to investors.Footnote 187

3.5 The Global ESG Advisory Industry

Several developments discussed above are supported by an array of commercial service providers that assist and advise investors with their ESG stewardship. This includes engagement firms, proxy advisers, data providers and consultants.Footnote 188 Investors use these specialist firms to access their expertise, supplement their in-house resources and expand the scope of their engagement activities.Footnote 189 Many of these organizations are multinational and use their international reach to assist investors with their global stewardship activities. For example, Sustainalytics, which is part of Morningstar group, offers engagement services on a global basis;Footnote 190 ISS ESG, the ESG consulting arm of Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS), also markets its ability to assist investors to engage with companies on ESG-related matters on a global basis.Footnote 191 Federated Hermes has a division, Federated Hermes EOS, which specializes in the provision of ESG-related engagement services to investors. Its engagement report for the first quarter of 2021 discloses that it undertook ESG-related engagements in Europe, Asia, North America, Australia and New Zealand.Footnote 192 In 2019, Federated Hermes EOS entered into an engagement services agreement with an Australian industry association representing Australia’s superannuation funds,Footnote 193 reflecting the global stewardship ambitions of the Australian funds.

Other service providers offer data and analysis to inform investors’ global stewardship activities.Footnote 194 RepRisk offers ESG data in relation to more than 170,000 companies extending to ‘all countries’, including emerging and so-called ‘frontier markets’.Footnote 195 A number of think-tanks and non-governmental organizations also provide ESG-related know-how and support to investors. For example, the Transition Pathway Initiative is a global initiative led by asset owners, supported by asset managers and drawing on the resources of FTSE Russell and the London School of Economics to develop resources for assessing companies’ preparedness for the transition to a low-carbon economy.Footnote 196 As of September 2022, 143 investors and their service providers from across the globe had pledged support for the Transition Pathway Initiative.Footnote 197

4 Implications of the Transnational and Collective Model of ESG Stewardship

The preceding discussion highlights that investors’ ESG stewardship is not simply a domestic phenomenon shaped only by local market factors. Rather, the development and practice of ESG stewardship today is underpinned by the cross-border interactions of the various ESG-focused non-state actors described above. This article calls this significant transnational phenomenon the global ESG stewardship ecosystem.

A distinguishing feature of any ecosystem is its interconnected nature.Footnote 198 This is certainly a hallmark of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem, whose various actors do not operate independently and in isolation. Instead, they interact closely with one another to form a highly networked, global movement. This partnership building is visible, for example, in the steps taken by the UN and its agencies to form links with the investment community through the establishment of the PRI, the Net-Zero Asset Owner and Asset Manager Alliances and the Investor Agenda. Indeed, the UN has an articulated strategy of seeking to realize its sustainability objectives through multi-stakeholder, public-private partnerships.Footnote 199A high degree of networking is apparent in other aspects of the ecosystem examined in this article. Both of the Net-Zero Alliances disclose, for instance, that they seek to work collaboratively with other investor alliances, including CA100+, in relation to climate change stewardship.Footnote 200 CA100+, in turn, brings together regional investor networks which assist in establishing and coordinating investor coalitions. Service providers, think tanks and non-governmental organizations also collaborate with these networks and coalitions. For example, Glass Lewis offers an ESG Climate Solutions Set, which is linked to focus-list companies nominated by CA100+;Footnote 201 the Transition Pathway Initiative is a member of a technical advisory group convened by CA100+;Footnote 202 and Federated Hermes EOS is an active participant in investor coalitions formed under the auspices of CA100+ and its regional networks.Footnote 203

Although international institutions and non-governmental organizations are key participants, institutional investors lie at the heart of this byzantine configuration and underpin its corporate governance significance. As highlighted in Sect. 3, institutional investors participate in initiatives by international institutions and non-governmental organizations with respect to the development of ESG norms and goals; they establish and operate transnational investor networks; they engage and work with ESG service providers; and they engage (often collectively) in ‘on the ground’ ESG stewardship and activism in the various markets where they operate. These activities are driving material developments in corporate governance. In the face of ESG stewardship, public companies and their boards are now providing greater disclosure,Footnote 204 agreeing to adapt their business models,Footnote 205 assenting to changes in senior personnel and at board level,Footnote 206 and linking their executives’ remuneration to the attainment of ESG-related milestones.Footnote 207

As a result, today, when any individual company is engaged by institutional investors in relation to an ESG issue, that engagement may be just the tip of the iceberg. That is, it may be the outworking of complex, often unseen, interactions occurring among multiple organizations within the global ESG ecosystem.

The existence and role of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem has significant implications for our understanding of both the potential and the regulatory implications of institutional investor participation in corporate governance. We explore the key implications below.

4.1 Global ESG Stewardship Indicates a Need to Refine the Conception of the Institutional Investor as ‘Rationally Reticent’ and the ‘Agency Capitalism’ Model

Leading scholars have expressed doubts about the corporate governance potential of institutional investors. Some of these doubts are jurisdiction-specific; for example, commentators have suggested that stewardship in a market can be constrained by local capital market structure, cultural differences or regulatory settings.Footnote 208 A little over a decade ago, Brian Cheffins, for instance, expressed doubts about the potential of the UK stewardship code on the basis that it did not extend to foreign investors, which are responsible for a sizeable proportion of investment activity in the United Kingdom.Footnote 209 On this analysis, the presence of foreign investors in the UK’s highly fragmented capital market was the ‘weak link’ in the United Kingdom’s efforts to promote investor stewardship.

Other doubts are based on long-standing concerns about whether institutional investors have the capacity and incentives to engage in the governance of their investee companies.Footnote 210 These concerns have only escalated in recent years as a result of the continuing growth of institutional investor share ownership and, in particular, the proliferation of indexed investorsFootnote 211 with particularly constricted incentives to participate in corporate governance.Footnote 212

Gilson and Gordon conclude that, in light of these incentive issues, institutional investors will, in general, adopt a default stance in corporate governance of ‘rational reticence’; that is, they will usually find it economically rational not to engage proactively in the governance of their investee companies.Footnote 213 Gilson and Gordon argue, however, that institutions may shed their reticence when other market participants with greater incentives to engage in corporate governance formulate and put proposals before them for consideration.Footnote 214 In this regard, they highlight the role played by hedge funds, which ‘monitor company performance and then … present to companies and institutional shareholders concrete proposals’.Footnote 215 According to Gilson and Gordon, hedge funds’ role is ‘an endogenous [market] response to the monitoring shortfall that follows from ownership reconcentration in intermediary institutions’.Footnote 216 In these circumstances, institutional investors act as a ‘swing’ constituency,Footnote 217 determining the outcome of proposals formulated by such other actors. So conceived, institutional investors are a reactive constituency that will engage in company-specific stewardship only when catalyzed by other market actors. Gilson and Gordon therefore conclude that, without more, stewardship codes are unlikely to prompt institutions to behave as proactive corporate stewards at the company level.

On the other hand, Gilson and Gordon recognize that it may sometimes make sense for highly diversified investors to invest in initiatives intended to address issues of broad relevance to their overall portfolios, for example, changes to corporate governance practices and norms.Footnote 218 The portfolio-wide relevance of such issues is likely to make them more financially material from the perspective of a diversified investor than activism designed to address a specific issue of strategy or performance at an individual investee company. More recently, Gordon has argued that it also makes sense for diversified investors to focus their engagement activities on issues involving systematic risk, such as climate change.Footnote 219 This is because such risk cannot be eliminated through diversification and must therefore be managed. Again, Gordon considers that such engagement is more likely to take the form of initiatives operating at a broader market level, for example, lobbying for regulatory change to compel companies to provide more comprehensive ESG disclosure to allow for more accurate pricing of systematic risk. Gordon doubts that diversified investors have the incentives to engage in company-specific ESG initiatives and considers that they are more likely to be responders to, rather than instigators of, such activism.Footnote 220

Our analysis of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem indicates that this paradigm of institutional investor stewardship requires refinement along a number of dimensions. First, our account of the ecosystem highlights a more complex division of labor in a system of ‘agency capitalism’ than Gilson and Gordon’s hedge fund / institutional investor model. Investors’ ESG stewardship is underpinned by an array of collaborative activity, including collective action through investor coalitions and networks and joint initiatives between institutional investors and international agencies, non-governmental activist organizations, and various service providers. Our review of the ecosystem demonstrates how these varied forms of collaboration enable investors to expand the breadth and depth of their ESG engagement and echoes other research which has emphasized the significance of collaborative activity in contemporary corporate governance.Footnote 221 The varied and evolved forms of collaboration in the global ESG stewardship ecosystem are additional endogenous responses to the concentration of share ownership in the hands of incentive-constrained institutional investors.Footnote 222

Second, this collaborative activity does not invariably involve institutional investors adopting a stance of rational reticence.Footnote 223 This article’s analysis instead shows the key role played by institutional investors in the global ESG stewardship ecosystem—one that frequently involves deliberate, strategic and coordinated behavior. CA100+, for instance, is a network of investors whose steering committee comprises representatives of a ‘who’s who’ of major institutional investors and regional investor networks.Footnote 224 CA100+ undertakes company-specific engagement against ‘focus companies’ in which institutional investors act as either ‘lead’ investors or ‘supporting’ investors.Footnote 225

Finally, our analysis of the ecosystem challenges the claim that institutional investor stewardship is more likely to involve engagement designed to change market-wide norms or practices than interventions focused on company-specific concerns. The ecosystem instead supports both macro-level initiatives (such as ESG norm development) and company-specific interventions (such as those conducted by CA100+ or the intervention against Rio Tinto). Even macro-level initiatives, such as attempts to compel market-wide disclosure of climate change risk and decarbonization commitments, are ultimately contributing to material changes in the underlying businesses of companies operating in carbon-intensive sectors. The breadth and depth of the ecosystem’s activities is therefore blurring the paradigmatic distinction between macro-level engagement and engagement directed at company-specific issues.

4.2 The Content of ESG Stewardship Is Not Solely Determined by Local Market Factors

The evidence presented in this article also highlights how the nature of ESG stewardship in a particular market will not necessarily be determined exclusively by domestic factors. ESG stewardship norms and practices in a market may instead be shaped by the activities of international agencies, transnational investor networks and globally active non-governmental organizations. The evidence demonstrates, in particular, how globally focused institutional investors may act as ‘importers’ of ESG stewardship norms and practices.Footnote 226 In markets with high levels of inbound institutional investor ownership, globally focused institutional investors may therefore exert significant influence on local ESG stewardship norms and practices.

This insight has important implications for national law makers and regulators. Owing to the diverse actors that inhabit the global ESG ecosystem, ESG stewardship norms and practices in a given market may be shaped by actors that do not have any formal responsibility for the development of such norms and practices at a local level.Footnote 227 Therefore, jurisdictions that do not currently have a stewardship code or other regulatory initiative addressing ESG stewardship prescriptively may find that they are subject to ESG stewardship norms and practices developed within the global ESG stewardship ecosystem.Footnote 228 As a result of its transnational nature, it cannot be assumed that the ecosystem will address ESG concerns which are considered material by local law makers and regulators, or will address such concerns in a manner acceptable to local law makers and regulators.Footnote 229 This issue is compounded by the expansive and evolving nature of the concept and meaning of ‘ESG’, which has been described as a ‘highly flexible moniker’ that can mean different things to different people.Footnote 230

In light of the dramatic growth in ESG stewardship, one international commentator recently argued that ESG stewardship ‘has the potential to become a very powerful driver towards a more sustainability-oriented future’ and, as a market phenomenon, is likely to provide a more dynamic and flexible means of achieving economic sustainability than mandatory regulation.Footnote 231 Law makers and regulators who may be attracted to this argument must appreciate, however, that leaving ESG stewardship ‘to the market’ will mean, among other things, that the nature and objectives of ESG stewardship are likely to be shaped to a significant extent, not just by domestic developments, but rather by the transnational activities of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem.Footnote 232

An even more fundamental issue can arise in these circumstances—namely, whether the influence of the global ESG ecosystem may affect the legitimacy of ESG stewardship from a local market perspective.Footnote 233 For example, to what extent are transnational developments consistent with governmental policy and/or the preferences of underlying beneficiaries in the local market?Footnote 234 Scholars have recently claimed that ESG stewardship can have particular economic relevance for institutional investors seeking to protect their highly diversified portfolios from undiversifiable systematic risk.Footnote 235 They have noted that it may make good economic sense for such investors to support shareholder proposals which have the effect of decreasing the value of systematically problematic companies in their portfolio (e.g., by putting pressure on oil and gas companies to make significant and value-decreasing changes to their businesses in order to manage climate change risk), provided that such decreases are outweighed by overall gains in their portfolio as a whole due to systematic risk mitigation. If ESG stewardship proceeds on this basis, what implications could it have in a market where domestic public companies are particularly exposed to these types of systematic risk? In these circumstances, the prospect of political backlash to investor stewardship is very real. This is highlighted by recent events in the United States where a number of Republican-controlled states are pursuing legislative or regulatory measures designed to constrain ESG investing and stewardship. This includes regulation prohibiting or limiting the scope for state entities (including public pension authorities) to consider ESG factors when investing state resources; initiatives to ‘blacklist’ investors which engage in divestment campaigns, boycotts or other forms of discriminatory behavior against fossil fuel companies; and regulation aimed at curtailing ESG-related activities of proxy advisers and other service providers to institutional investors.Footnote 236 At the federal level, a congressional committee has proposed legislative measures that would constrain the filing of ESG-related shareholder proposals under Rule 14a-8 and make voting on such proposals by shareholders more difficult.Footnote 237

Political pushback is not confined to the United States. During a 2021 inquiry conducted by the Australian Federal Parliament into ‘common ownership’ concerns, the committee chairperson, a member of the then conservative government, expressed concern about the increasing influence of Australia’s superannuation funds in the governance of Australian public companies.Footnote 238 The government’s concerns were founded in part on a perception that the industry superannuation funds were not supportive of its conservative policies owing to the funds’ historical ties to the Australian trade union movement.Footnote 239

The prospect of tension with local political and policy goals suggests that convergence of ESG stewardship norms and practices is unlikely to be seamless and is by no means assured. We return to this point below in Sect. 4.4.

4.3 Stewardship Codes Play a Somewhat Uncertain Role in the Global ESG Ecosystem

Stewardship codes are often regarded as having significant instrumental potential in developing stewardship norms and practices.Footnote 240 It has been argued, for example, that these codes have the potential to establish ESG stewardship norms and practices in markets that have not traditionally promoted sustainable investment, and that they can also assist investors in giving effect to ESG-related legal requirements in markets that already emphasize sustainable investing.Footnote 241 Although we do not dispute this potential for stewardship codes, nonetheless, we argue that codes’ capacity to play such a role must be assessed by reference to the global ESG stewardship ecosystem. As this article demonstrates, ESG stewardship has an extraordinary momentum that appears to be independent of, or at least not solely shaped by, stewardship codes.Footnote 242

In the past, it has generally been considered advantageous for stewardship codes to be non-prescriptive in nature, on the basis that this creates flexible regulatory instruments that can allow best practice to develop incrementally and responsively over time.Footnote 243 One of the implications of our analysis is that, although this stance is not necessarily inappropriate, policy makers and code issuers should, nonetheless, bear in mind the potential implications of such an approach in markets where transnational developments have considerable sway over market practice. An important implication in this context is that a non-prescriptive domestic code which provides investors with latitude through a ‘comply or explain’ approach may struggle to establish distinctive local norms and practices.Footnote 244 ESG stewardship may already be underway in the market, and actors in the global ESG ecosystem may be shaping the nature and extent of that stewardship. As a consequence, the issuer of such a code could find that ESG stewardship in that market evolves in unanticipated ways due to global pressures. This may present challenges if a local code issuer has a particular conception of ESG stewardship that differs from the norms and practices evolving within the global ESG stewardship ecosystem. In these circumstances, a more prescriptive approach towards stewardship in a particular market might be justified.Footnote 245

4.4 Novel Implications for the Convergence-Divergence Debate

Some aspects of the ESG stewardship ecosystem, such as the pivotal role played by international agencies and institutional investors, accord with Gordon’s identification of supranational forms of corporate governance convergence.Footnote 246 As Gordon has noted, convergence may be driven by a variety of factors.Footnote 247 Sometimes it is driven by companies themselves voluntarily adopting certain governance mechanisms to try to achieve a competitive advantage in a particular product or capital market.Footnote 248 However, according to Gordon, supranational forms of convergence also exist through:

-

(i)

international institutions, such as the OECD, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and the Financial Stability Board, endorsing certain corporate governance measures, which they believe will promote financial stability;Footnote 249 and

-

(ii)

institutional investors promoting particular governance techniques designed to foster stability and mitigate risk in their global investment portfolios.Footnote 250

The global ESG stewardship ecosystem encompasses both of these supranational forms of convergence, via its various actors, including international institutions, investor networks, and non-governmental organizations. The coordinated and collective nature of the activities undertaken by the ecosystem creates the promise of greater ESG convergence and harmonization.

On the other hand, a handful of factors may complicate the ecosystem’s ultimate impact in a local market. As already noted, tension may arise where the goals, norms, and practices promoted by the ecosystem are inconsistent with the expectations of national law makers and regulators. The variety of organizations in the ecosystem, any number of which may be sensitive to local interest group pressure or political or economic imperatives, also creates the possibility of regional or national variations in ESG stewardship norms and practices.Footnote 251 Moreover, the impact of the ecosystem may vary across ‘E’, ‘S’ and ‘G’ elements. It is notable that many of the examples in this article of the ecosystem’s activities relate to climate change, which is an issue of global significance. Although ‘S’ and ‘G’ issues also figure in the ecosystem,Footnote 252 they are currently less prominent in relative terms than climate change issues. It is conceivable that varying political, historical, legal and social context is resulting in different emphasis across jurisdictions on ‘S’ and ‘G’ issues.Footnote 253

This suggests that convergence in relation to ESG stewardship is unlikely to be seamless and that the ultimate effect of the global ESG stewardship ecosystem in a local market will be uneven and will depend on a range of local economic, institutional, social and political factors. In these circumstances, the possibility of what Gordon calls ‘divergence within convergence’ is very real.Footnote 254

Stewardship codes provide a clear example of the potential for divergence within convergence. Although the popularity of stewardship codes over the last decade might at first suggest formal convergence, stewardship codes around the world are far from uniform in the emphasis given to ESG issues.Footnote 255 One of the reasons for such ‘divergent convergence’ is that many jurisdictions have adopted these codes for different reasons and to address different problems.Footnote 256 Furthermore, a variety of organizations have responsibility for ‘writing the rules’ of stewardship codes. Some codes are written by regulators or quasi-regulators, whereas others are written by stock exchanges or investor associations.Footnote 257 Different authorship of stewardship codes can significantly affect not only their ESG content, but also issues relating to institutional investor activism, including whether collective activism is encouraged.Footnote 258 Moreover, the extent to which the norms embodied in stewardship codes are effective in practice may depend on the level of prescription in them, their coverage and who is responsible for monitoring compliance with them.Footnote 259

Recognizing ESG stewardship as an example of contingent convergence underscores two points. First, as noted earlier, local law makers and regulators must appreciate that the development of ESG stewardship norms and practices is not an exclusively national phenomenon. Second, the transnational nature of this phenomenon also creates uncertainty regarding the actual local implications of this phenomenon in national markets. What ultimately prevails in a local market from the interplay between the global ESG stewardship ecosystem and local factors will be uncertain and must be carefully considered by local law makers and regulators.

5 Conclusion

The rise of institutional investors’ ESG stewardship is a critical feature of contemporary corporate governance. It reflects fundamental themes of transnational law and has a momentum that defies the more pessimistic assessments in recent literature of institutional investors’ capacity and willingness to engage in stewardship.

Institutional investors’ ESG stewardship now forms part of an extensive global ecosystem of non-state actors. Understanding the nature and scope of that ecosystem, together with its activities and influence, is critical to understanding the full implications of several contemporary corporate governance debates and developments. These include the assumed ‘rational reticence’ of institutional investors, the nature of ‘agency capitalism’ and the role and potential of stewardship codes. More generally, the existence and activities of the ecosystem highlights that convergence may be underway in corporate governance, albeit in a complex way that defies simple predictions of its ultimate endpoint.

Notes

See Pargendler (2021) (expressing a preference for the term ‘international corporate law’ over alternative epithets, such as ‘transnational corporate law’ or ‘global corporate law’).

See Halliday and Shaffer (2015).

Pargendler (2021), p 1818 (describing international corporate law as ‘not monolithic, but fragmented, diverse, highly networked, and dynamic’).

Hill (2024).

See, e.g., Sustainalytics (2022).

Kell (2018).

Strine et al. (2020).

For further details, see infra Sect. 4.2.

See infra Sect. 2.2.

Gilson and Gordon (2013).

See, generally, Katelouzou and Puchniak (2022).

Gordon (2018), pp 28, 32, 41-44.

Bowley and Hill (2024), Part II.

See, generally, Pollman (2022).

Bowley and Hill (2024).

Responsible Investment Association Australasia (2020).

Ibid.

Bowley and Hill (2024), Part II.

For an analysis of the various methods of engagement employed by shareholders today, see Bowley et al. (2024).

See, generally, Katelouzou and Puchniak (2022).

Hill (2018).

See, e.g., BlackRock (undated).

See, e.g., Gilson and Gordon (2013).

ExxonMobil argued that the nominees would implement a ‘value-destructive agenda’: ExxonMobil, Letter to shareholders, 16 March 2021.

See Mufson (2021).

Vanguard held approximately 8.2% of ExxonMobil’s stock, BlackRock had a 6.7% stake and State Street owned 5.7%. See Herbst-Bayliss (2021).

See Alliance Advisors (2021).

ACCR (2021a). ACCR sought an annual vote on the adoption of a climate report, consistent with recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the Climate Action 100+ Benchmark. In February 2021, Rio Tinto became the first Australian-listed company to commit to a ‘say on climate’ vote, see ACCR (2021b). Santos and Woodside committed to adopting ‘say on climate’ votes in March 2021. Santos (2021); ACCR (2021c). Other Australian-listed companies to adopt a ‘say on climate’ vote in 2021 included Oil Search, AGL Energy, Origin Energy, and South32. See ACCR (undated).

Hohn (2021).

Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2021), p 7.

Ibid., p 11 (noting also that, in contrast, norms-based screening, positive screening and negative screening have each experienced a ‘more variable trajectory since 2016’).

BlackRock (2020), p 20. See also Papadopoulos et al. (2020) (reporting that in 2020 the European investment firm, AXA IM, had undertaken more engagement ‘than ever before’, targeting 181 issuers in a 6-month period in relation to matters concerning public health, workforce management, and shareholder rights); Legal & General (2020).

See further Bowley and Hill (2024), Part VI. It is worth noting, however, that BlackRock has since indicated that it is unlikely to support climate change-related proposals it considers to be too onerous on companies, given the economic and geopolitical challenges resulting from the conflict in Ukraine: Masters (2022).

Aberdeen Standard Investments (2020).

See, e.g., Becht et al. (2021) (examining ‘behind the scenes’ ESG engagement in Japan between institutional investors and portfolio companies via an equity ownership service, Governance for Owners Japan); Dimson et al. (2021), pp 2–3 (examining engagement projects coordinated by the Principles for Responsible Investment between 2007 and 15); Dimson et al. (2015), p 3227 (examining the ESG stewardship of a major institutional investor and reporting that it engages worldwide and, in 2014, had 4186 communications with investee companies regarding ESG matters).

Strine et al. (2020).

Ringe (2022), p 93.

Responsible Investment Association Australasia (2020), p 18.

See Gadinis and Miazad (2020) (arguing that attention to social risk can provide protection against downside risks to corporate value); Pollman (2021), p 666 (distinguishing ESG on this basis from its predecessor, corporate social responsibility, which is often viewed as involving ethical or moral principles); Ho (2016), pp 662–68 (discussing the economic rationales for risk-related shareholder activism and the link between non-financial and financial risks).

Williams (2021).

It has been said that the amended Directive effectively imposes a ‘duty to demonstrate engagement’ on institutional investors: Chiu and Katelouzou (2017).

Ringe (2022), pp 37–38.

Financial Reporting Council (2010).

See, generally, Katelouzou and Klettner (2022).

ACSI (2018), p 5.

Ringe points out that in some markets there is increasing client demand for such funds and that fund managers are often able to charge higher management fees in relation to such funds: Ringe (2022).