Abstract

Background and Objective

Inappropriate antimicrobial use can lead to adverse consequences, including antimicrobial resistance. The objective of our study was to describe patterns of prophylactic antimicrobial prescribing in Australian residential aged-care facilities and thereby provide insight into antimicrobial stewardship strategies that might be required.

Methods

Annual point prevalence data submitted by participating residential aged-care facilities as part of the Aged Care National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey between 2016 and 2020 were extracted. All antimicrobials except anti-virals were counted; methenamine hippurate was classified as an antibacterial agent.

Results

The overall prevalence of residents prescribed one or more prophylactic antimicrobial on the survey day was 3.7% (n = 4643, 95% confidence interval 3.6–3.8). Of all prescribed antimicrobials (n = 15,831), 27.1% (n = 4871) were for prophylactic use. Of these prophylactic antimicrobials, 87.8% were anti-bacterials and 11.4% antifungals; most frequently, cefalexin (28.7%), methenamine hippurate (20.1%) and clotrimazole (8.8%). When compared with prescribing of all antimicrobial agents, prophylactic antimicrobials were less commonly prescribed for pro re nata administration (7.0% vs 20.3%) and more commonly prescribed greater than 6 months (52.9% vs 34.1%). The indication and review or stop date was less frequently documented (67.5% vs 73.8% and 20.9% vs 40.7%, respectively). The most common body system for which a prophylactic antimicrobial was prescribed was the urinary tract (54.3%). Of all urinary tract indications (n = 2575), about two thirds (n = 1681, 65.3%) were for cystitis and 10.6% were for asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Conclusions

Our results clearly identified immediate antimicrobial stewardship strategies that aim to improve prophylactic antimicrobial prescribing in Australian residential-aged care facilities are required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Inappropriate antimicrobial use can lead to adverse consequences, including antimicrobial resistance. |

Of all prescribed antimicrobials (n = 15,831) in our residential aged-care facilities, 27.1% (n = 4871) were for prophylactic use; the most common body system for which a prophylactic antimicrobial was prescribed was the urinary tract (54.3%). |

Immediate antimicrobial stewardship strategies that aim to improve prophylactic antimicrobial prescribing are required. |

1 Introduction

Prophylactic antimicrobials can be prescribed to prevent an initial infection or to prevent the recurrence or reactivation of an infection [1]. Inappropriate prophylactic or therapeutic antimicrobial use can lead to adverse consequences, including local hypersensitivity reactions, toxicity, drug interactions, the selection of pathogenic organisms (such as Clostridium difficile), antimicrobial resistance and unnecessary additional healthcare costs [2, 3].

Australian residential-aged care facilities (RACFs), as part of their accreditation assessments, are required to demonstrate an antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) programme has been implemented [4, 5]. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes are a systematic approach to optimising the use of antimicrobials [6] and involve the appropriate prescribing of antimicrobials, including the optimal antimicrobial to treat their condition, at the right dose, by the right route, at the right time and for the right duration, based on an accurate assessment and timely review. Essential programme strategies include monitoring and reporting infections, antimicrobial use, and related outcomes in order to guide policy and practice change [7].

In Australia, there are approximately 2883 RACFs (2704 aged care homes and 179 multi-purpose health services that enable flexible health and aged care service options for small rural and remote communities). If required, clinical care at these facilities is mostly provided by personal care attendants, nurses, offsite general medical practitioners and accredited pharmacists. All Australian facilities are eligible to voluntarily participate in an annual Aged Care National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey (Aged Care NAPS). First implemented in 2015, this standardised point prevalence survey supports AMS programmes and is based on the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use in Long Term Care Facilities project [8].

It is of concern that an extensive use of antimicrobials in Australian RACFs has been consistently reported. The most recently published Aged Care NAPS report found the prevalence of residents prescribed at least one antimicrobial in 2019 was 8.2% [9]. A 10-year national-wide RACF study using linked pharmaceutical claims data showed most residents (86%) were dispensed an antibiotic at least once during the study period; the annual prevalence of antibiotic use increased from 63.8 to 70.3%, a 0.8% average annual increase (p < 0.001) [10]. A 3-year study using electronic health record data found the annual prevalence of antibiotic use across 68 RACFs decreased from 68.4% in 2015 to 63.4% in 2017, suggesting fewer residents were taking antibiotics but using them for longer [11].

The objective of our study was to specifically describe patterns of prophylactic antimicrobial prescribing in Australian RACFs using Aged Care NAPS data and thereby provide insight into AMS policy and practice strategies that might be required. The analyses presented in this article extend beyond those previously included in Aged Care NAPS reports [9].

2 Methods

2.1 Timeframe and Study Population

For our current study, 2016–2020 Aged Care NAPS data submitted by participating RACFs were extracted. Voluntary participation in the Aged Care NAPS for all years was encouraged via numerous communication strategies such as newsletters, direct correspondence (larger providers only) and Twitter. Participation by the 180 public RACFs located in Victoria was mandated by the State government in that jurisdiction.

2.2 Data Collection and Submission

Auditors, mostly nurses or pharmacists employed at the participating RACFs, were required to collect and submit de-identified data on a single survey day between June and August or June and December, dependent on the year. Standardised guidelines and online training sessions were provided on how to complete the survey, and if necessary, auditors could access e-mail and telephone support. Data were sourced from clinical histories and medication charts and were submitted via a web-based interface to a central database.

For those residents prescribed an antimicrobial on the survey day, data collected included antimicrobial selection, start date if known and less than or equal to 6 months (otherwise greater than 6 months or unknown), frequency including pro re nata, route of administration, therapy type (prophylaxis or therapeutic) and indication. The indication and body system (if known) were reported according to a standardised list. If an indication was not included on the list, the auditor was required to report ‘Other’ and the body system, for example, ‘Other—Urinary tract’. Whether the indication for commencing the antimicrobial and review or stop date was documented by the prescriber was also recorded.

2.3 Data Analysis

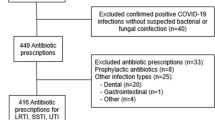

Data were analysed with Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All non-finalised resident records were excluded and for those RACFs that participated multiple times per year, only their most recent survey per year was included. All antimicrobials (antibacterial, antifungal and anti-parasitic agents) except antivirals were counted; methenamine hippurate, a urinary antiseptic sometimes prescribed to prevent recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) was classified as an antibacterial agent. For some analyses, prophylactic antimicrobials were sub-categorised as ‘systemic and topical combined’ or ‘systemic only’.

The prevalence of antimicrobial use was calculated as the proportion of residents present on the survey day who were prescribed at least one antimicrobial with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) derived using the binomial exact method. The proportion of prophylactic antimicrobials prescribed was determined by dividing the number of prophylactic antimicrobials prescribed by the total number of antimicrobials prescribed over all survey years. Prophylactic and total (prophylactic and therapeutic) antimicrobial prescriptions were compared to identify variations in prescribing practices (pro re nata orders, duration and documentation of indication, and review or stop date). The proportion of frequently prescribed prophylactic antimicrobials for different body systems (e.g. urinary tract) was calculated.

2.4 Ethics Review

Consistent with nationally defined quality assurance activities [12], no resident-identifying data were collected, and pooled data were captured for purposes of quality improvement within participating healthcare facilities. Ethical approval was therefore not required.

3 Results

During the study period, 1122 RACFs completed the Aged Care NAPS at least once and 126,137 residents were audited. All states and territories, remoteness groups and provider types were represented. Most participating RACFs were located in the states of Victoria (34.4%) and New South Wales (21.6%), and in major cities (48.2%) and regional areas (46.0%). About half (52.1%) were classified as ‘not for profit’, followed by ‘public’ (31.7%) and 'private' (16.2%).

Overall, 13,997 residents were prescribed one or more antimicrobial on the survey day, corresponding to a prevalence of 11.1% (95% CI 10.9–11.3). The overall prevalence of residents prescribed one or more prophylactic antimicrobial on the survey day was 3.7% (n = 4643, 95% CI 3.6–3.8). The overall prevalence of residents prescribed one or more prophylactic antimicrobial excluding methenamine hippurate was 3.0% (n = 3732, 95% CI 2.9–3.1).

Of all prescribed antimicrobials (n = 15,831), 27.1% (n = 4871) were for prophylactic use. Of these prophylactic antimicrobials, 87.8% were antibacterials and 11.4% antifungals; most frequently cefalexin (28.7%), methenamine hippurate (20.1%) and clotrimazole (8.8%). For systemic prescribed antimicrobials only (n = 9577), 42.3% (n = 4047) were for prophylactic use; most frequently, cefalexin (34.6%), methenamine hippurate (24.1%) and doxycycline (8.2%) (Table 1).

When compared to prescribing of all antimicrobial agents, prophylactic antimicrobials were less commonly prescribed for pro re nata administration (7.0% vs 20.3%) and more commonly prescribed greater than 6 months (52.9% vs 34.1%). The indication and review or stop date was less frequently documented (67.5% vs 73.8% and 20.9% vs 40.7%, respectively) (Table 2).

The most common body systems for which a prophylactic antimicrobial was prescribed were urinary tract (54.3%), skin, soft tissue and mucosal (18.1%), and respiratory tract (7.3%); the most frequently prescribed antimicrobial was cefalexin (40.2%), clotrimazole (43.2%) and doxycycline (49.7%), respectively (Table 3). Of all urinary tract indications (n = 2575), about two thirds (n = 1681, 65.3%), were for cystitis; 10.6% were for asymptomatic bacteriuria.

4 Discussion

Our study is the first of this scale to specifically evaluate the patterns of prophylactic antimicrobial use in Australian RACFs. Key findings included prolonged duration of use beyond 6 months (52.9%), and incomplete documentation of indication (67.5%) and review or stop date (20.9%). Comparison with similarly collected European Healthcare Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Use in Long Term Care Facilities project data [13] highlighted a relatively high prophylactic use (42.3% vs 29.4%) and the documentation of the review or stop date to be notably low (18.8% vs 64.6%) in our region. For both regions, prophylactic antimicrobials were most commonly prescribed for UTIs (65.5% vs 74.0%); most frequently in our study, cefalexin (40.2%), methenamine hippurate (34.1%) and trimethoprim (9.3%) and in the European study, trimethoprim (29.7%), nitrofurantoin (27.0%) and methenamine hippurate (11.6%). Implementation of simple AMS strategies [7] is required to improve prescribing of prophylactic antimicrobials in our RACFs, and thereby reduce risks for adverse consequences in vulnerable residents.

Prescribing of prophylactic antimicrobials should be according to standardised and evidence-based criteria. As a follow-up to our study, we plan to remind RACFs in our region that female residents prescribed antimicrobial prophylaxis for cystitis should have had at least two or more symptomatic infections within a 6-month period, or three or more infections within a 12-month period. Additionally, residents should be symptomatic [3]. As highlighted in other national campaigns [14], we will re-emphasise that antimicrobial therapy should not be prescribed for residents with asymptomatic bacteriuria.

There are no indications for which antifungal prophylaxis is indicated in immunocompetent patients. We identified clotrimazole to be the prophylactic antimicrobial most commonly prescribed for skin, soft tissue and mucosal indications. This should be reserved for the treatment of cutaneous candidiasis, seborrheic dermatitis and angular cheilitis [3]. With respect to prophylaxis for respiratory tract infections, expert advice should be sought before commencing prophylactic antimicrobial therapy for residents diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); antimicrobial prophylaxis should be “reserved for those who have severe COPD with recurrent exacerbations, in whom other treatments (for example, pulmonary rehabilitation) have been optimised” [15].

First-line antimicrobials, in comparison to second-line and third-line antimicrobials are usually recommended because of higher clinical effectiveness and/or fewer adverse effects. We believe that further evaluation is required to determine the reasons for prophylactic prescribing not being aligned with current prescribing guidelines [3]. For prophylaxis of UTIs in non- pregnant women, trimethoprim (first line), cefalexin (second line) and nitrofurantoin (third line) is recommended. It is noted that whilst bacterial resistance is avoided, evidence supporting the use of methenamine hippurate to prevent UTIs (commonly prescribed in our RACFs) is poor and inconsistent. Further, a recent study supported the use of macrolides before tetracyclines (doxycycline included) if prophylactic antimicrobial therapy is warranted for COPD management. Macrolides were more likely to prolong the time to the next exacerbation, improve quality of life and reduce serious adverse events [16].

In general, all antimicrobials should be prescribed for the shortest duration of therapy, consistent with the condition being treated and the patient’s clinical response [3]. In our RACFs, it is expected use of the new Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission user guide and clinical pathway for managing suspected UTIs will curtail prolonged continuous prophylaxis; these resources support an accurate interpretation of clinical assessments and the instigation of recommended actions [17]. Targeted improvement in documentation of review or stop dates will support consistent communication and may prompt more timely prescription amendments.

A potential limitation of our study is inherent to data extracted from point prevalence studies such as the Aged Care NAPS; prophylactic antimicrobials prescribed for longer durations are over-represented because they are more likely to overlap the survey day. Although not all Australian RACFs chose to participate in Aged Care NAPS, participation or non-response bias was not considered a major issue; as previously noted all states and territories, remoteness groups and provider types were represented. The many auditors in the different RACFs with diverse expertise were supported (e.g. user guide) to collect and submit standardised data.

5 Conclusions

Our findings clearly identified an improvement in prophylactic antimicrobial prescribing in Australian RACFs is required. Looking ahead, our immediate AMS policy and practice strategies supported by accreditation assessments will focus on constantly assessing if prophylactic antimicrobials are truly indicated, aligning prophylactic antimicrobial prescriptions with clinical guideline recommendations and always documenting key prescribing elements in residents’ clinical records.

References

Enzler MJ, Berbari E, Osmon DR. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in adults. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(7):686–701.

Schuts EC, Hulscher M, Mouton JW, Verduin CM, Stuart J, Overdiek H, et al. Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):847–56.

Antibiotic Expert Group. Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic. Version 16. Melbourne: Melbourne Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2019.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antimicrobial Stewardship in Australian Health Care. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2018.

Australian Government Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission. Guidance and resources for providers to support the aged care quality standards. Adelaide: Australian Government Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission; 2021.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antimicrobial stewardship clinical care standard. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2020.

Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. The core elements of antibiotic stewardship for nursing homes. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Prevention and Control; 2015.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Healthcare associated infections in long term care facilities in Europe: the HALT project. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthcare-associated-infections-long-term-care-facilities. Accessed 18 Jul 2022.

National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship and Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Antimicrobial prescribing and infections in Australian residential aged care facilities: results of the 2019 Aged Care National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2020.

Sluggett JK, Moldovan M, Lynn DJ, Papanicolas LE, Crotty M, Whitehead C, et al. National trends in antibiotic use in Australian residential aged care facilities, 2005–2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(12):2167–74.

Raban MZ, Lind KE, Day RO, Gray L, Georgiou A, Westbrook JI. Trends, determinants and differences in antibiotic use in 68 residential aged care homes in Australia, 2014–2017: a longitudinal analysis of electronic health record data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):883.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Ethical considerations in quality assurance and evaluation activities. 2014. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/e111. Accessed 18 Jul 2022.

Ricchizzi E, Latour K, Karki T, Buttazzi R, Jans B, Moro ML, et al. Antimicrobial use in European long-term care facilities: results from the third point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use, 2016 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2018;23(46):1800394.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: reducing inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing for aged care facility residents. Sydney: Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care; 2020.

Lung Foundation Australia and the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. The COPD-X plan: Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 2021. Brisbane: Queensland Lund Foundation Australia; 2021.

Janjua S, Mathioudakis AG, Fortescue R, Walker RA, Sharif S, Threapleton CJ, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;1: CD013198.

Australian Government Aged Care Quality and Safety Commission. AMS clinician resources 2021. https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/antimicrobial-stewardship/clinician-resources#clinical-pathway-for-suspected-urinary-tract-infections. Accessed 18 Jul 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the RACFs that have collected and submitted data as part of the Aged Care NAPS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

Noleen Bennett, Michael J. Malloy, Rodney James, Xin Fang, Karin Thursky and Leon J. Worth have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors whose names appear on the submission; (1) made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data; (2) drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; (3) approved the version to be published; and (4) agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bennett, N., Malloy, M.J., James, R. et al. Prophylactic Antimicrobial Prescribing in Australian Residential Aged-Care Facilities: Improvement is Required. Drugs - Real World Outcomes 9, 561–567 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-022-00323-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-022-00323-5