Abstract

Parental substance use, that is alcohol and illicit drugs, can have a deleterious impact on child health and wellbeing. An area that can be affected by parental substance use is the educational outcomes of children. Current reviews of the literature in the field of parental substance use and children's educational outcomes have only identified a small number of studies, and most focus on children's educational attainment. To grasp the available literature, the method from Arksey and O’Malley (2005) was used to identify literature. Studies were included if they were empirical, after 1950, and focused on children’s school or educational outcomes. From this, 51 empirical studies were identified which examined the relationship between parental alcohol and illicit drug use on children’s educational outcomes. Five main themes emerged which included attainment, behavior and adjustment, attendance, school enjoyment and satisfaction, academic self-concept, along with other miscellaneous outcomes. This paper highlights the main findings of the studies, the gaps in the current literature, and the challenges presented. Recommendations are made for further research and interventions in the areas of parental substance use and child educational outcomes specifically, but also for broader areas of adversity and child wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Parental alcohol and illicit drug use can have deleterious and enduring impacts on their children’s health and wellbeing (Kuppens et al., 2020; McGovern et al., 2018; Park & Schepp, 2015; Velleman & Templeton, 2016). Research has found that children who grow up in environments where their parents use substances are at higher risk for externalizing symptoms, such as hyperactivity (Finan et al., 2015; Hussong et al., 2010) and also internalizing symptoms, such as depression or anxiety (Lee & Cranford, 2008; Pisinger et al., 2016). These children can also be at greater risk for injury or infectious diseases (Crandall et al., 2006; Raitasalo et al., 2015). Furthermore, a large body of evidence highlights that parental substance use is associated with their own children’s substance use in adolescence (Chassin et al., 1993, 1996, 1999; Hussong et al., 2012).

While reviews of the literature on parental substance use have often included many health and wellbeing outcomes in their search strategy and subsequent findings, they continue to report a low number of studies regarding educational outcomes (Kuppens et al., 2020; McGovern et al., 2018; Park & Schepp, 2015; Velleman & Templeton, 2016). For instance, in Kuppens et al. (2020) only one study was identified that examined the longitudinal relationship between parental alcohol use and children’s academic achievement (McGrath et al., 1999). Likewise, McGovern et al. (2018) found three studies in their rapid review, and stated that there was a lack of research which considered children's educational outcomes following non-dependent parental substance use. Other reviews of evidence also cite a lower number of studies regarding children's educational outcomes, and perhaps this explains why education outcomes are not discussed at length compared to other health and wellbeing outcomes (Park & Schepp, 2015; Velleman & Templeton, 2016).

The lower attention given to educational outcomes in other reviews of literature is a concern when educational outcomes permit access to further and higher education, which have implications for later employment opportunities. Indeed, Howieson and Iannelli (2008) found that those who had lower educational attainment had poorer labor market outcomes by the time they were 22 to 23 years old. Given employment opportunities influence socioeconomic status, which is related to later health and wellbeing (Marmot, 2005) and disability free years (Melzer, 2000) a negative impact could have implications for life opportunities and satisfaction.

This is further warranted when problem substance use is concernedly prevalent. Recent estimates suggest that 3.7% of children have a parent known to alcohol and drug services, 15—24% have parents who used illicit drugs in the last year, and 14—37% have a parent who has an alcohol dependency (Galligan & Comiskey, 2019); these estimates are higher than older estimates presented by Manning et al. (2009). As a result, a large proportion of children could be at risk for lower educational outcomes and denied subsequent life opportunities. Therefore, as previous reviews in this area have found a small number of studies, a wider search strategy will be used to capture the extent of research exploring the relationship between parental substance use, that is alcohol or illicit drugs, and children’s educational outcomes.

Methods

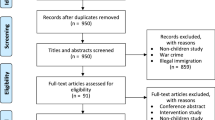

The review aimed to map out and synthesize the current research, while identifying the gaps in existing literature to draw conclusions from overall activity (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). The review was conducted using the guidance from Arksey and O’Malley, (2005) as the research question was broad and not well defined, and there was no quest to find answers from a narrow range of quality assessed studies. The guidance provides five steps: research question; identification; study selection; charting data; collating and summarizing the results.

Research Question

As in the guidelines, the research question remained broad—What is the relationship between parental substance use and children’s educational outcomes?

Identifying Relevant Studies

The search for literature started from late 2017 to mid-2018 using an array of sources. First, electronic databases were searched to identify literature using keywords such as ‘parental substance use’, ‘maternal alcohol’, ‘children of alcoholics’, ‘school attainment’, ‘school outcomes’, ‘educational achievement’, ‘academic attainment’ etc. Electronic searches were largely conducted on Google Scholar as grey literature, published studies, and doctoral theses could be identified simultaneously. Second, a hand searching of reports from key organizations (e.g., NSPCC) was conducted to identify literature. Third, the references of each source included were traced to identify further literature. Fourth, the citations were traced on all sources that were included. Lastly, existing networks, relevant organizations and conferences were used to identify any further literature. Once the main search had been conducted, a citation alert on highly cited papers in the area (e.g., Berg et al., 2016; Torvik et al., 2011) was created on Google Scholar to ensure the review was updated, and references and citations were traced as before. The inclusion of any research which was published after 2018, is a result of communication with existing networks or the citation alert.

Study Selection

The title was reviewed initially to determine the relevance of the publication, if relevant the abstract would be reviewed, and then the full-text. The inclusion criteria required the evidence to be empirical, which focused on both parental substance use and children’s educational (or school) outcomes; measures of IQ and cognitive functioning often appeared but were excluded as these coincided less with the educational system. Journal articles, doctoral theses, and other grey literature was included as it was peer reviewed; reviews of evidence were used only to identify literature via references or citations. The exclusion criteria included undergraduate or master’s dissertations, articles not in English, and research that was conducted before 1950. Articles that were not available via Cardiff University were requested via inter-library loans. Key literature was identified until a saturation point was reached where no new literature was identified (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

Charting of Data

The information of each empirical study was recorded in Microsoft Excel, as in Arksey and O’Malley (2005). The details included author; year of publication; study location; study population; measurement of substance use; study aims; methods; outcome measures, and key findings. This is approach is described more similar to a narrative review, as it uses a ‘describe-analytical’ method (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) and was used to collate the findings and identify themes.

Collating and Summarizing Results

The number of studies, their methods, location, and age could be reported in a descriptive sense. The findings of each study was recorded and collated into areas of subject focus, such as attainment, so useful comparisons could be made across sources and dominant findings could be identified. Through this, the research gaps were also identified and are later discussed.

Results

The review identified 51 empirical studies and eight reviews (Kuppens et al., 2020; McGovern et al., 2018; Park & Schepp, 2015; Smith, 1993; Velleman & Templeton, 2007, 2016; West & Prinz, 1987; Wilens, 1994). Note, reviews were only used to identify literature and do not feature in the main body of the findings. Table 1 summarizes information on each study, including the population and research focus. Most studies were conducted in the United States (26), Canada (5), Sweden (3), India (3), Denmark (3), and Spain (3). One study was found in each country of Russia, Greece, Slovenia, Brazil, Republic of Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Finland and Wales, UK; some studies included two countries in their population. Under a third of the studies were published since 2000 (19), 15 in the 1990s, 8 in the 1980s, 6 in the 1970s, and 3 in 1960s. Most of the literature explored parental alcohol use (41), whereas five studies examined illicit drug use, and poly-use. The literature was predominantly quantitative (48) compared to qualitative (2) or mixed-method (1). The findings are summarized in terms of the educational outcome areas of attainment, behavior and adjustment, attendance, academic self-concept, school enjoyment and satisfaction and other miscellaneous outcomes.

Attainment

Attainment was the most common outcome and the majority of studies evidenced a negative association between parental substance use and their children’s educational attainment. A number of longitudinal studies were identified, particularly in the last 10 years. Some of these studies used routine data to measure parental substance use in the form of hospital admissions, or parental alcohol problems (Berg et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2020; Gifford et al., 2015; Raitasalo et al., 2020) some of which had large population-level samples. Most studies found a negative association, for example Evans et al. (2020) found an increased risk of not attaining the expected grade at age seven years and eleven years, if the child had a parent with an alcohol admission or problem. Likewise, Raitasalo et al. (2020) found the likelihood of attainment was lower for children with parental alcohol problems, with maternal problems being a greater risk, and economic distress being a partial mediator. However, Berg et al. (2016) did not find a remaining significant negative association once models were adjusted for confounders.

Alongside this, a large number of observational studies were found. The largest study and most recent was Díaz et al. (2008) who compared 371 children of alcoholics to 147 matched controls; they found that children of alcoholics were nine times at risk of lower performance, and twice as likely to repeat a grade. Likewise, Sher et al. (1991) explored data from 253 children of alcoholics and 237 controls, and found that children of alcoholics had lower class ranks and test scores. However, a small number of observation studies did not find a significant difference. A qualitative study found that drug-using parents often were challenged by maintaining routine in the home, but teachers were mixed on their experiences of children, as some were still reaching their full potential (Hogan & Higgins, 2001). An earlier study by Hogan (1997) found that all teachers registered some concern about the attainment of children with drug-using parents, some with serious concerns which they anticipated would continue throughout the life course.

School Behavior and Adjustment

Studies also explored school adjustment, suspensions, exclusions, truancy, and early school departure. A population-level study by Torvik et al. (2011) found that children who frequently saw their parents intoxicated were more likely to have conduct problems; this finding was mirrored in other studies for alcohol (e.g., Puttler et al., 1998; Rydelius, 1981) and drug use (Hogan & Higgins, 2001; Sowder & Burt, 1980). However, McGrath et al. (1999) did not find this, and argued that the school environment promotes positive behaviors. However, qualitative research illuminated that children of substance users often had discipline issues at school, which were defined as impulsive or angry (Hogan, 1997; Kolar et al., 1994). In addition to adjustment, suspensions and exclusions were a key feature. A large study by Jennison (2014) found that parental alcohol use was associated with early departure from school, and a threefold increased risk of suspensions; this was mirrored in other studies (e.g., Díaz et al., 2008; Miller & Jang, 1977; Pinto & Kulkarni, 2012).

School Attendance

Some studies highlighted that the children of substance users were also at greater risk for poor school attendance (e.g., Gifford et al., 2015; McGrath et al., 1999; Sowder & Burt, 1980); this finding was found across longitudinal quantitative and cross-sectional qualitative research. Qualitative research elicited that poor attendance by some of the children had affected their educational progress, as some children had missed two months of school (Hogan, 1997; Hogan & Higgins, 2001). Likewise, Jeffreys et al. (2009) found that children experiencing parental substance use and maltreatment were more likely to be absent than children who experienced maltreatment alone.

Academic Self-Concept

Two studies focused on child academic self-concept (Gakhar & Jaswal, 2000; Hyphantis et al., 1991) this was measured by using self-rated performance at school by children. Hyphantis et al. (1991) found that children of alcoholics were less likely to rate themselves as ‘excellent’ or ‘very good’, and more likely to rate themselves as ‘good’, ‘moderate’, or ‘bad’. Likewise, Gakhar and Jaswal (2000) found that around half of the children of alcoholics rated themselves as ‘above average’ compared to children of non-alcoholics. The authors theorize that poor academic self-concept is related to lower self-esteem, insecurity, and feelings of being inferior due to the lower quality relationships in the home when a caregiver uses substances.

School Satisfaction and Enjoyment

Four studies explored school satisfaction and enjoyment across children whose parents used substances; the findings across studies were mixed. Torvik et al. (2011) found no association in school satisfaction; likewise, other studies found no differences in school enjoyment across children of substance-users and controls (Chandy et al., 1993; Sowder & Burt, 1980). However, Johnson and Rolf (1988) found that children of alcoholics disliked school more (28%) compared to controls (10%).

Miscellaneous

Across the research identified, some studies investigated outcomes that were niche. For instance, lower homework completion was explored by Hogan's (1997) qualitative study. Moreover a number of studies touched on the ‘special classes’ attended by children of substance users which were related to academic progress and discipline problems (Carbonneau et al., 2017; Knop et al., 1985; Kolar et al., 1994; Malo & Tremblay, 1997). Some studies also included the use and referral to the school psychologist by children of substance users (Knop et al., 1985; Schulsinger et al., 1986; Sowder & Burt, 1980). Overall, studies suggested that the school are often aware of problems in the family home and attempt to provide early support for affected children.

Discussion

This review was able to identify 51 empirical studies that explored the relationship between parental substance use and children’s educational outcomes. Five themes emerged in the literature which featured attainment, school behavior and adjustment, attendance, academic self-concept, school enjoyment and satisfaction, along with more miscellaneous outcomes. Attainment was the most commonly explored outcome across the studies, with children of substance using parents often attaining lower grades. Indeed, children experiencing parental substance use were more likely to have behavioral problems, lower attendance, and poorer academic self-concept. More niche findings included lower homework completion, and attendance of ‘special classes’ including referrals to the school psychologist.

While many reviews have focused on academic attainment and school behavioral problems to an extent, this review goes further to highlight how other aspects of educational outcomes are affected. For example, this review provided a more detailed account of behavioral problems in terms of conduct (Torvik et al., 2011), discipline issues (Kolar et al., 1994), attention deficit, and suspensions and exclusions (Jennison, 2014). Moreover, it documented lower attendance at school, and how qualitative work explored the impact this had (Hogan & Higgins, 2001). Attention was also given to how children perceive themselves at school, termed as academic self-concept, and how self-esteem may impact on educational outcomes. This recognition of broader educational outcomes may elude to potential mechanisms between childhood adversity and educational attainment; for example, how low attendance was described as an explanation for slower academic progress, or how challenging behavior often led to classroom removal, which decreased the time spent learning.

Moreover, this review highlighted studies which also identified how the school can be a protective factor for some children experiencing adversity. Most studies did not find a difference in school enjoyment and satisfaction between the children who had substance using parents and those who did not. Perhaps it is plausible to posit that if the school is identified as a safe environment by the child, it can be used to provide support to children experiencing substance use. Smith (1993) discusses the value of school-level interventions for children of substance users, and argues that the school can foster good teacher–pupil relationships, and provide routine when children’s family or home environment is chaotic.

From this review, the author encourages researchers to include educational outcomes when considering childhood adversity. While considerable attention has been given to the domains of mental health and wellbeing, substance use and injury, greater attention is needed on educational outcomes. Research shows educational attainment has important implications for socioeconomic position, subsequent life opportunities and health (Marmot, 2005) such as suicide (Bjorkenstam et al., 2011) or drug abuse (Gauffin et al., 2013). Given that domains of health and wellbeing can cascade to others (Masten et al., 2004) the inclusion of a broader range of outcomes would benefit how we understand and navigate childhood adversity.

While the review found considerable literature, a number of significant gaps in the field remained. First, there is a lack of research on children where parents use illicit drugs (Barnard & McKeganey, 2004) as few studies examined this, and most were dated before 2001 (Brook et al., 2010; Chandy et al., 1993; Gifford et al., 2015; Hogan, 1997; Hogan & Higgins, 2001; Jeffreys et al., 2009; Kolar et al., 1994; Moss et al., 1995; Sowder & Burt, 1980). Second, and building on the previous point, fewer studies considered parental poly-use of substances, which is a concern when Raitasalo et al. (2015) found that poly-use has a greater association with child hospital admissions. Moreover, research on parental substance use dynamics has found that behaviors can be mirrored, and heavier substance users often have a higher likelihood of poly-use (Lowthian et al., 2020). Third, studies should consider comparing estimates using different measurements of substance use (e.g., dependence vs. binge drinking) as studies largely differed; for example, some research used hospital admissions (Evans et al., 2020), dependence (Díaz et al., 2008) or quantity (Mangiavacchi & Piccoli, 2018). It is also advised that studies ensure that they adjust for key confounders, as some studies included did not do this, and this limits interpretability. Given the link between deprivation and adversity (Bellis et al., 2014) and some studies finding no association once models were adjusted (Berg et al., 2016) research must include confounders.

Lastly, very few studies considered the mechanisms, or potential mediators in the relationship between parental substance use and children’s educational outcomes. Brook et al. (2010) used a small sample to examine whether the mother–child relationship was a mediator between parental substance use and academic achievement; they found moderate evidence that substance use decreases the mother–child relationship, which was concerning, as this had a positive association with academic achievement. Given that reviews of this field often point towards household dysfunction and parenting being key explanations (Kuppens et al., 2020; McGovern et al., 2018; Park & Schepp, 2015; Velleman & Templeton, 2016) future research and interventions (e.g. Dawe et al., 2003) must evaluate the contribution of parenting and the family environment to confirm associations and pathways.

While this review has consolidated a body of research, it is limited by the non-systematic strategy used. Hence, it is strongly recommended that a systematic review is conducted, given the volume of literature found in this review that has not been identified in others. A systematic review will provide a more robust method for identifying literature, and also can evaluate the studies in terms of methodological quality. Nevertheless, this review has confirmed that most studies found a negative association between parental substance use and a broad range of children’s educational outcomes. In addition, it has identified research gaps in terms of parental drug use, poly-use and mechanisms. Following this, there are a number of research recommendations to improve our understanding, which may better inform interventions and strategies for supporting families experiencing substance use, and childhood adversity more broadly.

References

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Aronson, H., & Gilbert, A. (1963). Preadolescent sons of male alcoholics: An experimental study of personality patterning. Archives of General Psychiatry, 8(3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1963.01720090023002

Barnard, M., & McKeganey, N. (2004). The impact of parental problem drug use on children: What is the problem and what can be done to help? Addiction, 99(5), 552–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00664.x

Bellis, M. A., Lowey, H., Leckenby, N., Hughes, K., & Harrison, D. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences: Retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. Journal of Public Health, 36(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdt038

Berg, L., Bäck, K., Vinnerljung, B., & Hjern, A. (2016). Parental alcohol-related disorders and school performance in 16-year-olds—A Swedish national cohort study. Addiction, 111(10), 1795–1803. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13454

Bjorkenstam, C., Weitoft, G. R., Hjern, A., Nordstrom, P., Hallqvist, J., & Ljung, R. (2011). School grades, parental education and suicide—A national register-based cohort study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 65(11), 993–998. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.117226

Braggio, J. T., Plshkln, V., Gameros, T. A., & Brooks, D. L. (1993). Academic achievement in substance-abusing and conduct-disordered adolescents. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(2), 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199303)49:2<282::AID-JCLP2270490223>3.0.CO;2-N

Brook, J. S., Saar, N. S., & Brook, D. W. (2010). Developmental pathways from parental substance use to childhood academic achievement. The American Journal on Addictions, 19(3), 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00037.x

Carbonneau, R., Vitaro, F., & Tremblay, R. E. (2017). School Adjustment and Substance Use in Early Adolescent Boys: Association With Paternal Alcoholism With and Without Dad in the Home. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(7), 1008–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431617708054

Casas-Gil, M. J., & Navarro-Guzman, J. I. (2002). School characteristics among children of alcoholic parents. Psychological Reports, 90(1), 341–348. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2002.90.1.341

Chandy, J. M., Harris, L., Blum, R. W., & Resnick, M. D. (1993). Children of alcohol misusers and school performance outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 15(6), 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/0190-7409(93)90029-9

Chassin, L., Curran, P. J., Hussong, A. M., & Colder, C. R. (1996). The relation of parent alcoholism to adolescent substance use: A longitudinal follow-up study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105(1), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.105.1.70

Chassin, L., Pillow, D. R., Curran, P. J., Molina, B. S., & Barrera, M. (1993). Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: A test of three mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3

Chassin, L., Pitts, S. C., DeLucia, C., & Todd, M. (1999). A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: Predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(1), 106–119.

Connolly, G. M., Casswell, S., Stewart, J., Silva, P. A., & O’brien, M. K. (1993). The effect of parents’ alcohol problems on children’s behaviour as reported by parents and by teachers. Addiction, 88(10), 1383–1390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02025.x

Crandall, M., Chiu, B., & Sheehan, K. (2006). Injury in the first year of life: Risk factors and solutions for high-risk families. The Journal of Surgical Research, 133(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2006.02.027

Dawe, S., Harnett, P., Rendalls, V., & Staiger, P. (2003). Improving family functioning and child outcome in methadone maintained families: The Parents Under Pressure programme. Drug and Alcohol Review, 22(3), 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/0959523031000154445

Díaz, R., Gual, A., García, M., Arnau, J., Pascual, F., Cañuelo, B., Rubio, G., de Dios, Y., Fernández-Eire, M. C., Valdés, R., & Garbayo, I. (2008). Children of alcoholics in Spain: From risk to pathology. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0264-2

Evans, A., Hardcastle, K., Bandyopadhyay, A., Farewell, D., John, A., Lyons, R. A., Long, S., Bellis, M. A., & Paranjothy, S. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences during childhood and academic attainment at age 7 and 11 years: An electronic birth cohort study. Public Health, 189, 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.08.027

Finan, L. J., Schulz, J., Gordon, M. S., & Ohannessian, C. M. (2015). Parental problem drinking and adolescent externalizing behaviors: The mediating role of family functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 43, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.001

Fine, E. W., Yudin, L. W., Holmes, J., & Heinemann, S. (1976). Behavioral disorders in children with parental alcoholism. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 273(1), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1976.tb52922.x

Gakhar, S., & Jaswal, I. J. S. (2000). Self-concept and academic performance of adolescent children of alcoholics (COAs). The Anthropologist, 2(1), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09720073.2000.11890620

Galligan, K., & Comiskey, C. M. (2019). Hidden Harms and the Number of Children Whose Parents Misuse Substances: A Stepwise Methodological Framework for Estimating Prevalence. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(9), 1429–1437. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2019.1584224

Gauffin, K., Vinnerljung, B., Fridell, M., Hesse, M., & Hjern, A. (2013). Childhood socio-economic status, school failure and drug abuse: A Swedish national cohort study. Addiction, 108(8), 1441–1449. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12169

Gifford, E. J., Sloan, F. A., Eldred, L. M., & Evans, K. E. (2015). Intergenerational effects of parental substance-related convictions and adult drug treatment court participation on children’s school performance. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85(5), 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000087

Haberman, P. W. (1966). Childhood symptoms in children of alcoholics and comparison group parents. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 28(2), 152–154. https://doi.org/10.2307/349271

Hill, S. Y., Locke, J., Lowers, L., & Connolly, J. (1999). Psychopathology and achievement in children at high risk for developing alcoholism. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(7), 883–891. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199907000-00019

Hogan, D. (1997). The social and psychological needs of children of drug users: Report on exploratory study. Children’s Research Centre, Trinity College Dublin.

Hogan, D., & Higgins, L. (2001). When parents use drugs: Key findings from a study of children in the care of drug-using parents. [Report]. Children’s Research Centre. http://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/5061/

Howieson, C., & Iannelli, C. (2008). The effects of low attainment on young people’s outcomes at age 22–23 in Scotland. 34(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920701532137

Hussong, A. M., Huang, W., Curran, P. J., Chassin, L., & Zucker, R. A. (2010). Parent alcoholism impacts the severity and timing of children’s externalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(3), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9374-5

Hussong, A. M., Huang, W., Serrano, D., Curran, P. J., & Chassin, L. (2012). Testing Whether and When Parent Alcoholism Uniquely Affects Various Forms of Adolescent Substance Use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(8), 1265–1276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9662-3

Hyphantis, T., Koutras, V., Liakos, A., & Marselos, M. (1991). Alcohol and drug use, family situation and school performance in adolescent children of alcoholics. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 37(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076409103700105

Jacob, T., & Windle, M. (2000). Young adult children of alcoholic, depressed and nondistressed parents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61(6), 836–844.

Jeffreys, H., Hirte, C., Rogers, A., & Wilson, R. (2009). Parental substance misuse and children’s entry into alternative care in South Australia. South Australia. Department for Families and Communities.

Jennison, K. M. (2014). The impact of parental alcohol misuse and family environment on young people’s alcohol use and behavioral problems in secondary schools. Journal of Substance Use, 19(1–2), 206–212. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659891.2013.775607

Johnson, J. L., & Rolf, J. E. (1988). Cognitive functioning in children from alcoholic and non-alcoholic families. British Journal of Addiction, 83(7), 849–857. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00520.x

Kammeier, M. L. (1971). Adolescents from families with and without alcohol problems. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 32(2), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.15288/qjsa.1971.32.364

Knop, J., Teasdale, T. W., Schulsinger, F., & Goodwin, D. W. (1985). A prospective study of young men at high risk for alcoholism: School behavior and achievement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 46(4), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1985.46.273

Kolar, A. F., Brown, B. S., Haertzen, C. A., & Michaelson, B. S. (1994). Children of substance abusers: The life experiences of children of opiate addicts in methadone maintenance. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 20(2), 159–171.

Kuppens, S., Moore, S. C., Gross, V., Lowthian, E., & Siddaway, A. P. (2020). The Enduring Effects of Parental Alcohol, Tobacco, and Drug Use on Child Well-being: A Multilevel Meta-Analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 32(2), 765–778. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579419000749

Lee, H. H., & Cranford, J. A. (2008). Does resilience moderate the associations between parental problem drinking and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors? A study of Korean adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 96(3), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.007

Lowthian, E., Moore, G., Greene, G., Kristensen, S. M., & Moore, S. C. (2020). A latent class analysis of parental alcohol and drug use: Findings from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Addictive Behaviors, 104, 106281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106281

Malo, J., & Tremblay, R. E. (1997). The impact of paternal alcoholism and maternal social position on boys’ school adjustment, pubertal maturation and sexual behavior: A test of two competing hypotheses. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 38(2), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01853.x

Mangiavacchi, L., & Piccoli, L. (2018). Parental alcohol consumption and adult children’s educational attainment. Economics & Human Biology, 28, 132–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2017.12.006

Manning, V., Best, D. W., Faulkner, N., & Titherington, E. (2009). New estimates of the number of children living with substance misusing parents: Results from UK national household surveys. BMC Public Health, 9(377). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-377

Marcus, A. M. (1986). Academic achievement in elementary school children of alcoholic mothers. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198603)42:2<372::AIDJCLP2270420228>3.0.CO;2-B

Marmot, M. (2005). Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet, 365, 6.

Masten, A. S., Burt, K. B., Roisman, G. I., Obradovic, J., Long, J. D., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1071–1094. British Nursing Database; ProQuest Central.

McCarthy, W. J., & Anglin, M. D. (1990). Narcotics addicts: Effect of family and parental risk factors on timing of emancipation, drug use onset, pre-addiction incarcerations and educational achievement, narcotics addicts: effect of family and parental risk factors on timing of emancipation, drug use onset, pre-addiction incarcerations and educational achievement. Journal of Drug Issues, 20(1), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/002204269002000107

McGovern, R., Gilvarry, E., Addison, M., Alderson, H., Geijer-Simpson, E., Lingam, R., Smart, D., & Kaner, E. (2018). The association between adverse child health, psychological, educational and social outcomes, and nondependent parental substance: A rapid evidence assessment. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018772850

McGrath, C. E., Watson, A. L., & Chassin, L. (1999). Academic achievement in adolescent children of alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60(1), 18–26.

McLachlan, John. F. C., Walderman, Rodeen. L., & Thomas, S. (1973). A study of teenagers with alcoholic parents (pp. 1–60) [Research Monograph]. Donwood Institute.

Melzer, D. (2000). Socioeconomic status and the expectation of disability in old age: Estimates for England. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 54(4), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.54.4.286

Miller, D., & Jang, M. (1977). Children of alcoholics: A 20-year longitudinal study. Social Work Research and Abstracts, 13(4), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1093/swra/13.4.23

Moss, H. B., Vanyukov, M., Majumder, P. P., Kirisci, L., & Tarter, R. E. (1995). Prepubertal sons of substance abusers: Influences of parental and familial substance abuse on behavioral disposition, IQ, and school achievement. Addictive Behaviors, 20(3), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(94)00077-C

Murphy, R. T., O’Farrell, T. J., Floyd, F. J., & Connors, G. J. (1991). School adjustment of children of alcoholic fathers: Comparison to normal controls. Addictive Behaviors, 16(5), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(91)90020-I

Nylander, I. (1960). Children of alcoholic fathers. Acta Paediatrica, 49(3), 313–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1960.tb07739.x

Offord, D. R., Poushinsky, M. F., & Sullivan, K. (1978). School performance, IQ and delinquency. The British Journal of Criminology, 18(2), 110–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjc.a046885

Park, S., & Schepp, K. G. (2015). A systematic review of research on children of alcoholics: Their inherent resilience and vulnerability. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(5), 1222–1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9930-7

Pinto, V. N., & Kulkarni, R. N. (2012). A case control study on school dropouts in children of alcohol-dependent males versus that in abstainers/social drinkers’ children. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 1(2), 92–96. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.104944

Pisinger, V. S. C., Bloomfield, K., & Tolstrup, J. S. (2016). Perceived parental alcohol problems, internalizing problems and impaired parent—Child relationships among 71 988 young people in Denmark. Addiction (abingdon, England), 111(11), 1966–1974. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13508

Poon, E., Ellis, D. A., Fitzgerald, H. E., & Zucker, R. A. (2000). Intellectual, cognitive, and academic performance among sons of alcoholics during the early school years: Differences related to subtypes of familial alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(7), 1020–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04645.x

Puttler, L. I., Zucker, R. A., Fitzgerald, H. E., & Bingham, C. R. (1998). Behavioral outcomes among children of alcoholics during the early and middle childhood years: Familial subtype variations. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 22(9), 1962–1972. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb05904.x

Raitasalo, K., Holmila, M., Autti-Rämö, I., Notkola, I. L., & Tapanainen, H. (2015). Hospitalisations and out-of-home placements of children of substance-abusing mothers: A register-based cohort study. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12121

Raitasalo, K., Østergaard, J., & Andrade, S. B. (2020). Educational attainment by children with parental alcohol problems in Denmark and Finland. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072520968343

Reich, W., Earls, F., & Powell, J. (1988). A comparison of the home and social environments of children of alcoholic and non-alcoholic parents. British Journal of Addiction, 83(7), 831–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00518.x

Robins, L., N., West, P., A., Ratcliff, K., S., & Herjanic, B., M. (1977). Father’s alcoholism and children’s outcomes. Currents in Alcoholism, 4, 313–327.

Rydelius, P. A. (1981). Children of alcoholic fathers. Their social adjustment and their health status over 20 years. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica, 286, 236–245.

Schulsinger, F., Knop, J., Goodwin, D. W., & Teasdale, T. W. (1986). A prospective study of young men at high risk for alcoholism: Social and psychological characteristics. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43(8), 755–760. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080041006

Serec, M., Švab, I., Kolšek, M., Švab, V., Moesgen, D., & Klein, M. (2012). Health-related lifestyle, physical and mental health in children of alcoholic parents. Drug and Alcohol Review, 31(7), 861–870. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00424.x

Sher, K. J., Walitzer, K. S., Wood, P. K., & Brent, E. E. (1991). Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427

Smith, G. H. (1993). Intervention strategies for children vulnerable for school failure due to exposure to drugs and alcohol. The International Journal of the Addictions, 28(13), 1435–1470. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089309062193

Sowder, B. J., & Burt, M. R. (1980). Children of heroin addicts: An assessment of health, learning, behavioral, and adjustment problems. Praeger.

Tarter, R. E., Hegedus, A. M., Goldstein, G., Shelly, C., & Alterman, A. I. (1984). Adolescent sons of alcoholics: Neuropsychological and personality characteristics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 8(2), 216–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05842.x

Torvik, F. A., Rognmo, K., Ask, H., Røysamb, E., & Tambs, K. (2011). Parental alcohol use and adolescent school adjustment in the general population: Results from the HUNT study. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 706. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-706

Velleman, R., & Templeton, L. (2007). Understanding and modifying the impact of parents’ substance misuse on children. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13(2), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.106.002386

Velleman, R., & Templeton, L. J. (2016). Impact of parents’ substance misuse on children: An update. Bjpsych Advances, 22(2), 108–117. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.114.014449

Vitaro, F., Dobkin, P. L., Carbonneau, R., & Tremblay, R. E. (1996). Personal and familial characteristics of resilient sons of male alcoholics. Addiction, 91(8), 1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.91811618.x

West, M. O., & Prinz, R. J. (1987). Parental Alcoholism and Childhood. Psychopathology, 102(2), 2014–2218.

Wilens, T., & E. (1994). The child and adolescent offspring of drug- and alcohol-dependent parents. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 7, 319–323.

Zanoti-Jeronymo, D. V., & Carvalho, A. M. P. (2005). Self-concept, academic performance and behavioral evaluation of the children of alcoholic parents. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 27(3), 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462005000300014

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my PhD supervisors, Professor Graham Moore and Professor Simon Moore, who both offered full support over the course of my study. I am grateful for Dr Heather Trickey, who offered guidance, and explained the process in a straightforward, no nonsense manner! I am grateful to Jodie Luker, who gave the manuscript a much needed proofread. Finally, I would like to thank the Cardiff University library service, who processed all of my inter-library loans with diligence and kindness.

Funding

This research was funded by an ESRC Wales Doctoral Training Centre (DTC) PhD Studentship at Cardiff University. This work was supported by Health Data Research UK, which receives its funding from HDR UK Ltd (HDR-9006) funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation (BHF) and the Wellcome Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Emily Lowthian has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lowthian, E. The Secondary Harms of Parental Substance Use on Children’s Educational Outcomes: A Review. Journ Child Adol Trauma 15, 511–522 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00433-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00433-2