Abstract

The idea of this paper is inspired by the dismal experience and lessons from the initially ineffective global (WHO-led) response to the 2014–2016 West African Ebola virus epidemic. It charts the evolution of global health policy and governance in the post-World War II international order to the current post-2015 UN Sustainable Development Goals era. In order to respond adequately existing and emerging health and development challenges across developing regions, the paper argues that global health governance and related structures and institutions must adapt to changing socio-economic circumstances at all levels of decision-making. Against the background of a changing world order characterised by the decline of US-led Western international liberalism and the rise of the emerging nations in the developing world, it identifies the ‘Rising Powers’ (RPs) among the emerging economies and their soft power diplomacy and international development cooperation strategy as important tools for responding to post-2015 global health challenges. Based on analysis of illustrative examples from the ‘BRICS’, a group of large emerging economies—Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa—the paper develops suggestions and recommendations for the RPs with respect to: (1) stimulating innovation in global health governance and (2) strengthening health systems and health security at country and regional levels. Observing that current deliberations on global health focus largely, but rather narrowly, on what resource inputs are needed to achieve the SDG health targets, this paper goes further and highlights the importance of the ‘how’ in terms of a leadership and driving role for the RPs: How can the RPs champion global governance reform and innovation aimed at producing strong, resilient and equitable global systems? How can the RPs use soft power diplomacy to enhance disease surveillance and detection capacities and to promote improved regional and international coordination in response to health threats? How can they provide incentives for investment in R&D and manufacturing of medicines to tackle neglected and poverty-related diseases in developing countries?

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: Framing Global Health Diplomacy and Global Power

At the end of World War II, the dominant world order was a US-led Western, multifaceted, liberal international system organised around multilateral and governance institutions created to promote and sustain economic growth, stability and prosperity, security cooperation and democratic solidarity (Ruggie 1982; Smith 1994; Cox and Sinclair 1996; Mandelbaum 2004). After seven decades of dominance, this model of ‘liberal internationalism’ is now under pressure in a rapidly changing world order. The world is already a different place than it was at the turn of the millennium or even a decade ago. The election of a US President, Donald Trump, in November 2016, who is openly hostile to multilateralism on virtually all issues of economic and security cooperation is contributing in no small measure to the fading of liberal internationalism and decline in the importance of global institutions and the rules of post-war Pax Americana (Ikenberry 2018; Norrlof 2018). International liberalism has also been threatened by the rise of far-right ‘populist’ regimes and nationalisms across the democratic world (Jahn 2018). Furthermore, Britain’s decision to leave the EU seems to be having a stressful and divisive effect on European solidarity, which could further undermine the current liberal world order. These changes in the international order are also impacting existing global governance mechanisms (structure, process and agenda) and leading towards a transition or shift in global power distribution and leadership (Kagan 2017; Layne 2018).

As the Trump administration continues to self-inflict a declining leadership role for the USA in the international order in pursuit of its narrow ‘America First’ nationalist agenda, the ‘Rising Powers’ (RPs) among the larger emerging economies—China, India, Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia, Mexico, among others—are using their growing economic weight to secure an increasingly important role in the definition of global policies and goals, including through demands for a larger role in major global governance institutions (Kirton 2015; Kliengibiel 2016; Layne 2018). The RPs are now among the most enthusiastic actors in global negotiations aimed at building a post-2015 international order around the fulfilment of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which rather ambitiously seek to ‘end poverty, in all its forms, everywhere’ and tackle marginalisation and inequality.

An important early indication of growing influence of the RPs on the architecture of global governance was the 1999 shift in global economic power with the transformation of the G8 into the G20 and with the inclusion of China and other key emerging economies, among them India, Turkey, Indonesia and South Africa, as the premier forum for international economic cooperation (Keohane 2001; Ullrich 2008; Kahler 2013; Kirton 2015). At the same time, the RPs have maintained a noticeably strong and increasingly influential presence in the United Nations system and other existing multilateral global institutions (WTO, World Bank, IMF). As they become responsible stakeholders in these institutions, the RPs now demand reforms in their governance structures, thereby challenging the existing order. In addition to creating their own parallel or alternative institutions in their preferred image, the RPs view existing global institutions as enablers for the legitimisation of their international engagement. This reveals a new, multi-order tension between the post-Cold War and the newly emerging order. On which side the RPs throw their influence will have a profound effect on which order prevails: a renewed liberal order, or a new, possibly illiberal order.

In the light of the above, it is not surprising therefore that two of the dominant themes of scholarly discussion in international relations over the past decade have been global governance and rising powers. Underlying both are weighty questions about which norms, principles and power relations characterise and which should influence governance in the global order. Central questions are: how the world should be ordered; who is responsible for addressing global problems in various domains; are there alternatives to existing governance structures and how can change be managed; how can governance be organised so as to confer benefit on peoples across the globe equitably (Gill and Benatar 2006).

This paper explores important conceptual and practical issues and contemporary challenges of global governance under the impact of the growing influence of the RPs alongside the retreat of the once pre-eminent US and European countries. It focuses specifically on the domain of health. Unlike most of the other spheres of global governance (e.g. finance, trade, climate change, intellectual property rights, labour), health is indeed a truly ‘global’ phenomenon in the sense that affects the well-being of all humanity and is regarded as right—as enshrined in the 1948 constitution of the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The inspiration for this paper stems from the current crisis in global health, perhaps, most catastrophically manifested by the failure of health systems at all levels to respond promptly and adequately to the 2014–2016 West Africa Ebola virus epidemic that killed over 11,300 persons in the three most affected countries, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, and affected several other nations in Africa, Europe and the USA. Lessons from this particular health tragedy—which exposed both the world’s vulnerability to global epidemics and also the extreme effects of the crisis in an unequal global health system—suggest that the determinants of good health are much broader than a single-issue and distinctive governance structure and that the separation or ‘siloing’ of various issues in the current global health architecture is inappropriate because these are in fact linked both conceptually and logistically in an operational context.

The above example illustrates how health intersects with economics and order. In addition, recent studies show that economic development and better health lead on the one hand to the epidemiological transition and also to increased migration (which, when dealing with avian flu to TB, poses a health risk): this raises the stakes for countries, especially RPs wherein most migration will take place, to address both health and health economics. Both liberal democracies and RPs can and must show a new way forward, since the old institutions and nationalisms are inadequate to conceive of and cope. How they might do so is part of the focus of this article.

Indeed, from the perspective of SDG 16—to build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions—the growing importance of the RPs in global negotiations and forums indicates that they can become a source of reform in global (and regional) institutions that could change existing norms and practices for addressing an array of international development challenges (Kliengibiel 2016; Kahler 2013).

Health, which can justifiably be conceptualised as a ‘global public good’, is the domain where the fusion of the normative and change in the global order is perhaps most distinct and potentially impactful (Dodgson et al. 2002; Woodward et al. 2002; Garrett 2007; Schaferhoff et al. 2015). Global health governance provides a good illustration of the notion of change in the world order as both a cause and effect the rise of new powers among the emerging nations and the challenges they pose to the existing structures which are largely the vestige of the post-World War II global distribution of power. The paper examines how the convergence of the emerging nations—collectively (e.g. global south–south or regional cooperation) and individually (bilateral partnership)—acts within the framework of soft power development diplomacy to bring about ‘desirable’ modifications to existing global health policy and governance aimed at contributing to the fulfilment of the post-2015 health Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets (Sekalala 2017; Sehovic 2017). The growing influence of the RPs on current global health architecture could in the future result in global health governance looking radically different from where it stood prior to 2015 (Cooper et al. 2007; Cooper and Kirton 2009; Harman and Lisk 2009; Kickbusch et al. 2016).

In its simplest form, global health governance refers to the framework of international norms, rules and principles that define and shape the way by which societies make and implement collective decisions (i.e. global health policy) to respond to health problems and challenges in the context of specific national and common transnational interests (Lee et al. 2002; Ruger 2012; WHO 2014; Kickbusch and Szabo 2014). The intersection of traditional and RP influence here is evidenced, for example, in Thailand’s lead in the UN’s Foreign Policy and Global Health Initiative (FPGHI) as well as that country’s national and international efforts to promote both the SDGs and Universal Health Coverage (UHC). We are witnessing a link between global health (diplomacy) and development (international cooperation)—involving new lead actors, non-state actors (NGOs, private organisations joining with national and local governments). In this regard, the paper analyses how and to what extent Rising Powers are poised to introduce needed patterns of innovation in ideas and institutions to global health policy and governance responses, but also maintains that core elements of existing post-World War II institutions are required for the ongoing transformation of the international order. Innovations in global governance are thus required, including those that diverge from the model of formal, intergovernmental organisations.

The paper draws on the example of the BRICS group of emerging economies—Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa—to illustrate the role of the RPs in the global health arena, both from the standpoints of new configurations of actors and possible future shift in the global balance of power through governance innovation (Kirton et al. 2014). This group of five major emerging economies comprises over 40% of the world’s total population, accounts for nearly 30% of world GDP and has a share of about 24% in world trade. Globally, the political and economic influence of the BRICS is rapidly increasing. Although some BRICS member countries, China and India for example, have been engaged in development cooperation with countries in Africa and Asia for decades, their role as influential development actors has only recently been acknowledged in both the literature and in terms of power distribution in the international order. Once themselves aid recipient countries, these RPs are becoming ‘donors’ in their own right; rather than simply being a beneficiary of global public goods, they are now actively generating and sustaining development In this transition, they are influencing how development is done.

The purpose of the analysis is not to provide an exhaustive narrative of the health-oriented programmes and soft power development diplomacy of the BRICS in the context of the larger sphere of the global order. Instead, it is to show how important proactive, collaborative and coordinated soft power diplomacy efforts can be for facilitating needed governance innovations and shaping global health policy and what are limitations in reality. The BRICS group of large emerging nations is moving into a position where it can contribute to various programmes and institutions that impact on global health and its governance. These programmes and institutions are not limited to a narrow range of medical-related issues (e.g. responding to pandemics, availability of drugs, capacity strengthening of domestic health systems, R&D, etc.), but include a broader international development cooperation framework that leverages power and accountability, shared responsibility, legitimacy as well as ideology, social and cultural issues that directly and indirectly affect health outcomes. This approach provides a good basis to better understand the events and factors in both development diplomacy and global health policy that enable the RPs to assume a leading role in influencing and introducing governance innovations.

The paper is structured as follows. Following the above introduction which presents an overview of the concept and practice of global health governance under the impact of growing influence of the RPs in the international order, the next section reviews the current global health architecture and governance process in the light of a changing world order. This is followed by an exploration of opportunities for the Rising Powers, through the prism of soft power diplomacy of the BRICS, to play a leading role in global health policy as an integral part of the international development cooperation agenda and through championing global health governance innovations aimed at greater equity in health systems delivery and financing. It looks at the engagement of the BRICS with different aspects of global health governance and its institutions, focussing on efforts to enunciate alternatives to the current structures of global health governance through new and existing arrangements. The paper ends with a critical appraisal of the strategy, impact and limit of the RPs in their efforts to create new institutional mechanisms through governance innovations that could improve global health policy and enhance the fulfilment of the objectives and targets of the health component of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

2 Global Health Architecture and a Changing World Order: Policy Issues and Governance Implications

The adoption of the International Sanitary Regulations in 1851 by the international sanitary conference organised by the French Government marked the first effort towards international cooperation in public health. The aim of these regulations was to standardise international quarantine rules and guidelines for managing and controlling the spread of infectious diseases at the time, specifically cholera, plague and yellow fever. Though not referred to as such, the scientific foundation of health security through international cooperation was further strengthened and consolidated through 13 more international sanitary conferences held in Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century (Howard-Jones 1975). The establishment of the World Health Organisation (WHO) within the United Nations system in 1948 provided a global multilateral framework for monitoring, regulating and managing health risks and promoting health diplomacy. The WHO became the ‘standard setter’ for global health policy within the context of the international community, and setting the global health agenda, establishing norms and guidelines and engaging partners for international health policy development and implementation. In 1969, the WHO’s World Health Assembly adopted the first International Health Regulations (IHRs) which were revised and updated by the Assembly in 2005 within an environment of global health diplomacy. In the context of the post-war global order, the WHO was unique in terms of its legitimacy as the only international institution with a mandate to promulgate international law within the context of global diplomacy for ensuring health security.

The start of the twenty-first century began well for global health, with the governments of 189 countries signing on to the UN Millennium Declaration in 2000 and committing themselves to the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which highlighted the important contribution of health to the overarching objective of poverty reduction. The Declaration firmly acknowledged the need to address the root causes of ill health as an important means towards its objective. The first decade of the new millennium saw a flurry of activities and initiatives in the health field, which led some observers across the international community to label this period as ‘the grand decade for global health’. Several new players appeared on the global health scene, including institutions and initiatives such as UNAIDS, Stop TB Partnership, Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI), Roll Back Malaria, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Gates Global Health and Clinton HIV/AIDS Foundations, and UNITAID, some of which were designed to deliver life-saving interventions on a massive scale.

Political leaders from the world’s most advanced industrial and emerging economies (G7/8 and later G20) incorporated health global health issues into the globalisation response agenda at their annual meetings, resulting in some of the most innovative health initiatives (Chatham House 2010; Kirton 2015; Larionova and Kirton 2015). Individual G8 and G20 members had their own particular priorities regarding global health challenges: Japan focused on fighting global pandemic through the lens of human security; France addressed inequality of access to health services and medicines; the UK called for massive investments and financial transfers from rich to poor countries to fight poverty, perceived as the main driver of poor health status. The launching of the multi-billion dollar US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2003 gave a big boost to official development aid for health (disease treatment, vaccines and medicines) which more than tripled over the decade. More significantly in terms of global health diplomacy, this initiative represented the strategic use of health interventions in selected developing countries to achieve foreign policy goals of the donor country (Daschel and Frist 2015; Michaud and Kates 2012; Feldbaum et al. 2010).

The grand decade also saw the establishment of multi-sectoral (public–private) operative partnerships and a shift from a system-focused towards a problem-focused approach to health challenges emphasising demand-driven funding (Buse and Walt 2000a, b; Buse 2004; West et al. 2017). Under this scenario, collaborative public–private efforts towards finding solutions to global health problems often involved the exploitation of market dynamics to stimulate investment in research and production capacity for medical products and to drive prices down. At the same time, multilateral organisations and national governments entered into open-ended discussions with civil society organisations, private philanthropic foundations and academics to find solutions to some of the largest health problems facing the global community (Khoubesserian 2009; Moran and Stevenson 2013). Significantly from a governance standpoint, the role of non-state actors (NSAs) in civil society in the success of some of these ventures should not be underestimated: without the moral voice and protests of the AIDS activist movement, it is unlikely that the decisions made by political leaders and multilateral agencies would have been as bold as they were or the financial commitments as large as they were.

The growth of these global health initiatives in the grand decade reflected an awareness of the inadequacy of the traditional responses of WHO and other multilateral development agencies to recognise the urgency of global health problems in the 1980s and 1990s. As the Cold War wound down, what some described as unipolar moment emerged which emphasised democratisation over development. Health was not an integral part of the overall development agenda at the time; this lack of interest in health matters was due predominantly to the framing of the role of the state in the national development process essentially in economic terms. What did eventually bring the increase in global health initiatives in the post-cold war era was a convergence between the development and security agendas particularly in the context of the burgeoning HIV/AIDS pandemic (Buzan et al. 1998). This link was necessary to ensure that health issues received the resources necessary to respond. However, over time, this development focus morphed into a predominantly security focus to the point where the response to infectious diseases was no longer part and parcel of health as a global public good but rather as a way of preventing bioterrorism and providing security. This linkage was counterproductive as it distorted health governance agenda and created competitive convergences, as reflected in the North–South power relationship divide (e.g. G7 v African countries) in negotiations. Such a securitised (Buzan et al. 1998; Enemark 2017) approach to global health governance in effect undermined the validity and legitimacy of existing international level organisations (e.g. WHO).

Despite the wave of new global health initiatives which characterised the grand decade of global health, key indicators of global health status (e.g. reduction in child mortality; improvements in maternal health; proportion of population with access to affordable essential medicines, ratio of qualified healthcare personnel to total population) did not register significant improvements. Single-disease initiatives favoured by prevailing global health policy were not complemented by the strengthening of domestic health systems, as is required for strong and accessible healthcare services. This fundamental weakness in global health policy—neglect of health systems in poor countries—was due to lack of policy coherence at all levels, as well as to gaps and distortions in resource allocation which neglected the poorest and most vulnerable in society. In reality, policy coherence in global health did not evolve fast enough to ensure that emerging globalisation and development issues (challenges and problems) related to public provision of health care were aligned at national, regional and multilateral levels (Lin and Kickbush 2017). Further evidence that the global health architecture was not effective in achieving health improvements on a sustainable basis can be deduced from the unsatisfactory progress towards the achievement of the health-related UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) between 2000 and 2015.

The increasing complexities of political and economic institutional arrangements at global and regional levels, and their interplay with developmental policies at national level, have also undermined policy coherence in global health architecture. This is perhaps best exemplified by the landmark TRIPS agreement adopted by the WTO (the Doha Declaration of 2001). At the time it was considered a watershed in terms of balancing the need for economic incentives and commercial interests of dominant pharmaceutical companies in the global north with the need of developing countries for improved access to essential and life-saving medicines at affordable cost. Unfortunately, as the experience and outcome of the TRIPS agreement subsequently showed, the existence or introduction of powerful donor-driven bilateral and multilateral trade and economic agreements undermined the necessary multi-level policy coherence in development, trade and public health policies needed to enable developing countries benefit from S (Aginam 2005; Lisk 2010; Sekalala 2017).

Globalisation also brought about changes in patterns of health and disease worldwide, which in turn affected the basis on which decisions on health were made globally (Cornia 2001; Woodward, et al. 2002; Labonté and Gagnon 2010). On the positive side, globalisation fostered the creation of new possibilities for the spread of information and knowledge and resource mobilisation to save lives, increase life expectancy and improve the quality of human health and life. But globalisation also contributed to the spread of disease and death globally due to the rapid increase in economic and social interconnectedness of the world brought about mainly by low-cost communications and budget travel. Globalisation also increased awareness of economic, political and social environments elsewhere which, for example, enabled healthcare professionals badly needed in their own poor countries in the global south to migrate to better jobs and opportunities in richer countries in the north. These changes beg the question: how can states across the globe collectively protect and promote health in an increasingly globalised world?

The failure of international organisations to respond to emerging health challenges, particularly with respect to new diseases, has its root in imbalances in global decision-making power. This inadequacy can be best underscored by the frequently referenced ‘10/90 gap’, by which only 10% of global health research funding is dedicated to the diseases that affect the poorest 90% of the world’s population (Kirton et al. 2014). In the case of the WHO, decisions concerning the allocation of resources to various health problems are largely determined by a few powerful member states and their interests as reflected in their dedicated voluntary funding. In contrast, the organisation’s regular budget, which is used for its core operations, has declined steadily in real terms. Most notably, funding of core work in health emergencies and epidemic and pandemic response has been significantly reduced. In the 6 years leading up to the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the WHO’s budget for infectious disease outbreak and crisis response was reduced from US$ 469 million for 2009–2010 to $241 million for 2014–2015.

The challenges posed by the necessity to tackle an increasing array of global health problems within the institutional framework of the WHO have given rise to evolving and changing patterns of global health diplomacy and processes of agenda setting and negotiations. These processes are conducted at country, regional and international levels, and mechanisms have been established to coordinate. Under the current global health architecture, certain elements of governance (process and agenda), institutional structures (e.g. WHO) and policy initiatives (UNAIDS, GFATM plus bilateral ODAs) have emerged as key to the dominant response to global health problems.

Global health governance is now coming under threat anew mainly because of declining US commitment to global health security under the Trump administration. This was exemplified first by the administration’s failure to seek renewed foreign aid funding in 2017 to sustain the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and USAID post-Ebola investments in infectious disease preparedness, resulting in significant scaling down of CDC’s presence and activities in sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, the administration’s 2018 proposal to return an unspent amount of US$ 252 million in residual Ebola emergency response funds from the 2014–2015 outbreak to Congress could instead have gone towards combating future outbreaks. These developments point towards an abandonment of US global investments in health security preparedness and a reduction in resources available for future outbreak response. The dissolution on the part of the Trump administration of the US governments’ capabilities to effectively manage either of those things has been further compounded by the position of a global health security preparedness czar having become an early casualty of John Bolton’s National Security Council leadership reshuffles. Before the Trump administration took an axe to it, the USA contributed an estimated US$ 10 billion a year throughout the ‘grand decade of global health’, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. It is now expected to fall from the current US$ 10 billion to about US$ 6 billion.

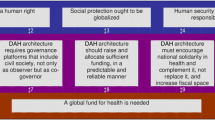

In summary, the global health governance structures set up at the end of World War II had gaps and weaknesses which made them relatively ineffective in responding to current and evolving global health challenges. These gaps have turned dire: with respect to the future directions in global health governance, there is now more or less widespread consensus that only through improved international cooperation and collective action based on a new form of global health diplomacy can governments address the multiple and complex global public health problems and challenges of the future. Responses to current global health risks and deficits require new set of actors, institutions and processes. It is in this regard that the soft power diplomacy efforts of the RPs are examined below.

3 Responding to Post-2015 Global Health Challenges Through Soft Power Diplomacy of the RPs: The Case of BRICS

The soft power diplomacy of the RPs builds on the strategic priorities of the grand decade of global health, including medicine (prevention and treatment of diseases, access to essential drugs), economics (trade, finance) and human security (rights and social justice). These define a global health landscape characterised by the interrelationship between justifications for and the object(s) of pursuing good health. These are also underpinned by certain normatively based values, ideas and belief systems—such as diplomacy, accountability, cooperation, partnership and innovation—emphasised in the role(s) of different actors, agendas and diplomacy modalities.

While the advent of new global health initiatives and non-state actors in the 2000s changed the pattern of health financing in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Africa, challenges for global health governance, especially in relation to right and equity, remain. These relate to key questions: How can greater commitment be ensured by all countries towards the provision for health as a global public good? How can political support be gained for global health action addressing hitherto neglected health needs of the developing regions—e.g. neglected tropical diseases, malnutrition? How can the voice of developing countries be ensured in global health governance when pitted against powerful political and commercial vested interests in developed countries? These complex global health challenges create space for new kinds of action shaped by the realities of global engagements and shifting economic and political power relationships, and present opportunities for governance innovation and institutional change (Scharferhoff et al. 2015; Kickbusch et al. 2016). Today, the global health architecture cannot rely solely on the post-World War II aid-related, traditional north–south divide governance structures. The RPs have the potential to change global health governance structures into a new architecture that is both universal and transformative, grounded in the realities of people’s health needs and aspirations.

Prior to 2015, the RPs were already increasing their influence in global governance in major areas of economics, politics and culture. As the US retrenched its leadership and as Europe dithered over its assumption, the RPs, among them BRICS, Turkey and Indonesia, acting counter-cyclically, increasing international contacts and seeking opportunities for deepened interactions covering various domains through soft power diplomacy and investments (Brautignam 2010; Kirton et al. 2014; Kickbusch et al. 2016; Lin and Kickbush 2017). In addition, the RPs boosted economic and political advances through the establishment of the New Development Bank and the Asia Investment Infrastructure, which now rival the World Bank and regional development banks as development financial institutions.

BRICS emphasises the principles of cooperation and multilateralism in global engagements, and the ‘BRICS brand’ is developed and shaped through cooperation among emerging and developing countries. Beyond benefitting the BRICS alone, the organisation’s and member states’ ability to cooperate and deliver on initiatives and summit decisions reflects positively on their capabilities to introduce innovations to global governance. In a global environment characterised by economic volatility and increased regional tensions, BRICS as a group is striving to create a unique space for itself in global development cooperation (Kirton et al. 2014).

BRICS has positioned itself as an advocate of fair globalisation and global free trade that benefit the global South, and has aimed to become a force that advances the cause of a just, equitable and integrated multi-polar world order. As a consistent advocate of transformation in global governance (including opposing unilateralism and powers that undermine a rule-based multilateral world), the geographic spread and political diversity of BRICS membership represent an asset for strengthening south–south cooperation and increasing the soft power impact of the group collectively as an organisation and individually as member states. BRICS as such serves as a flagship of major emerging nations: its member states to acquire prestige from participating in the bloc.

Health first appeared on the BRICS agenda as a discussion point at the third BRICS summit in China in 2011. The focus was on HIV/AIDS. Since then, the group has held annual meetings devoted to health. In 2012, BRICS health ministers also decided to meet every year on the sidelines of the WHO Assembly. Inter-BRICS health cooperation is gaining momentum and represents a promising channel for improving global health governance. Such cooperation—based on individual countries’ capacities and comparative advantages—provides member countries with a valuable platform to share their experiences and cooperate to address key public health issues including neglected tropical diseases and towards the achievement of universal health coverage (UHC) in accordance with the SDGs. This can benefit other developing countries, particularly in Africa, which bears a disproportionately high share of the global burden of disease and also suffers from the largest capacity deficits with respect to infrastructure and human resource for healthcare service delivery. Indeed, China, as the leading BRICS nation, has offered much-needed medical aid to African countries. What has been dubbed ‘health diplomacy’ has become an important facet of BRICS soft power foreign policy strategy for African countries.

The growing presence of BRICS on the global health scene represents a shift in the political and economic burdens in health governance. It is now recognised that exemplary and innovative public health programmes and policies are emerging from developing country economies and are transforming global healthcare practices. Key BRICS contributions include affordable generic medicines to manage HIV and TB; different health service delivery systems and innovative diagnostic tools; and production of various vaccines for the global market against pandemic influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, hepatitis, etc. In addition to promoting south–south cooperation in the health domain, BRICS has also been active in promoting triangular cooperation in global health, which involves the collaboration between a traditional donor from the OECD/DAC, an emerging power from the global South as a technical partner, and a beneficiary developing low-/middle-income country—for example, Japan/UK financing, Brazil/India building the infrastructure and providing training and Mozambique/Uganda benefiting in the form of a fully operational hospital facility.

Such is the magnitude and diversity of activities by the BRICS nations in the field of health development in recent years that the group can seriously now be considered a new force in global health, capable of acting as a unified bloc on matters of global health policy and governance and with new set of priorities that often contrast with the dominant western health development paradigm. Reflecting this, it is worth noting that the BRICS nations were instrumental in securing the election of a developing region candidate (Ethiopia’s Foreign Minister, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus) to the top position of Director-General of the WHO in 2017. Within his first full year in office, the new DG published an innovative ‘Concept Note on the WHO 2019–2023 Programme of Work’. The Concept Note covers key policy and governance themes for the future direction of the WHO, including the role of the organisation in offering advice and providing technical support for achieving UHC, regional and global coordination of operations, and setting of standards and global norms for reducing global health inequality. Such is the magnitude and diversity of activities by the BRICS nations in the field of health development in recent years that the group can seriously now be considered a new force in global health, capable of acting as a unified bloc on matters of global health policy and governance and with new set of priorities that often contrast with the dominant western health development paradigm.

The BRICS member states are now contributing to reshaping global health cooperation—positioning themselves as ‘development partners’ rather than as donors—a significant distinction significant in global governance. The nature, modalities and responsibilities that apply to south–south cooperation differ from those of north–south cooperation. The medical aid that the China provides to developing countries includes sending doctors overseas for extended period to operate Chinese-built hospitals and clinics and training African health personnel, which the northern countries do not do. There are also Chinese medical teams working in Africa sponsored by Chinese private sector organisations and companies, another difference. By the end of 2010, China had sent 17,000 medical workers to 48 African countries, treating 200 million African patients, according to the Chinese Ministry of Health. It was reported that in 2009 alone, 1324 Chinese medical professionals worked in 130 institutions in 57 developing countries: of that number, more than 1000 Chinese doctors were in 40 African countries alone (Anshan 2011). The majority of Chinese foreign medical aid funds has gone into building hospitals and clinics, establishing malaria prevention and treatment centres (over 40 anti-malarial prevention and treatment centres have been built in African countries in the past decade and approximately US$ 50 million of anti-malarial medicines distributed); despatching medical teams for AIDS, tuberculosis and Ebola control and treatment; and providing medicines and equipment (Huang 2017). The Chinese government is now broadening its focus to include maternal and child health care as well as nutrition-related non-communicable diseases. Such health diplomacy has become an effective foreign aid ‘relations-building’ strategy for the Chinese. It should, however, be noted that China’s foreign aid investments in health development in Africa usually involve the execution of projects tied to Chinese companies and foster Chinese exports, hence constituting mutual benefits (‘win–win’) for both China and recipient countries. Similar provisos have also been identified with regard to health aid from India to a number of African countries.

BRICS nations doubled their foreign assistance to support health initiatives in the developing world between 2009 and 2014, covering capacity-building, access to affordable medicines and the development of new tools and strategies for health system strengthening (Kirton et al. 2014). Such is the growing importance of the BRICS in global health that the WHO devoted its June 2014 monthly news bulletin to the theme of ‘BRICS and Global Health’. The bulletin reported that inter-BRICS health cooperation has become a valuable platform for knowledge exchange and transfer particularly with regard to the risks and threats of epidemics and how to treat neglected tropical and poverty-related diseases. Already by 2014 BRICS nations were producing high-quality and affordable medicines, vaccines, diagnostic and other high technologies that strengthen health systems in the poorer areas of the world. BRICS sees the global heath agenda as giving priority to partnerships with other developing countries through bilateral and multilateral mechanisms and the implementation of south–south and triangular cooperation projects.

BRICS is also committed to supporting existing international health-oriented organisation such as the WHO, UNAIDS and UNICEF and global and regional health partnerships. In some ways, the priorities of BRICS in health policy are different to those of the OECD countries and even contrast with the dominant western health development paradigm in certain areas. BRICS promotes a global health discourse informed by its members own experiences, and its development cooperation with developing countries is based on stated partnership and equity. This pattern of engagement may result in innovations in global health governance that diverge from the model of traditional intergovernmental organisations. Rather than producing and relying on formal agreements for promoting global public health, governance is influenced by a variety of formats linked to development cooperation and soft power diplomacy initiated by the rising emerging powers themselves and in cooperation with the recipient countries as partners, and where applicable in coordination with multilateral organisations.

4 The Rising Powers and Global Health Governance Innovation: A Reassessment of Strategy and Impact

We have observed that global health governance can be influenced by soft power diplomacy and new modes of international development cooperation act as change agents in a rapidly changing world order. Since the turn of the millennium, the world has witnessed a deliberate and increasing incursion into the global health arena by RPs, influencing innovative governance. It is important to assess the role of the RPs and their impact on contemporary global health architecture from the standpoints of policy and institutional reforms towards more equitable partnerships and power relationships, and with regard to the effectiveness of this role in anticipating and combatting global health challenges. While the contribution of RPs such as BRICS through soft power diplomacy has undoubtedly led to some improvement in global health and strengthening of domestic health systems, health insecurity in terms of the right to good health and the knowledge and resources for responding to the complexity of contemporary global health challenges remains in a large swathe of the developing world and particularly Africa. The present international system for preventing and responding to health risks and challenges needs to be overhauled especially in terms of the instruments (rules and policy) and the multiple institutions (purpose, principles and priorities) of global health governance.

There are gaps and weaknesses in the current global health architecture with respect to institutional coordination and policy harmonisation, which reinforce inequalities in health status and ability to respond to existing and new health challenges between and within regions and countries. Some of these challenges indicate necessary normative enquiries concerning the implications of emergent redistributions of economic and political power for the sustainability of and legitimacy of an equitable global health policy and new forms of global health governance. Certain proposals for reform and innovative mechanisms favoured by the RPs for responding to concerns about current global health governance structures also raise important questions of accountability, global shared responsibility, development effectiveness of health aid and suitability in specific political or economic context. Although soft power health diplomacy interventions by the RPs could promote and deepen support for new forms of global health governance, it is also clear that there could be difficulties and tensions in seeking to fundamentally alter existing global governance structures. RPs involvement in global health governance is not an easy or set solution.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted at the UN in late 2015 as a set of universal goals and targets to which all countries agreed and are expected to implement, represent a positive step towards recognising that rights and equity are fundamental to the success of healthy and sustainable societies in the post-2015 international development framework. The SDGs provide an opportunity to integrate health within the broader development agenda and, if implemented creatively and innovatively, the achievement of the specific health component (SDG 3) and other health-related SDGs and targets can be enhanced through improved governance of global health. For the SDGs to make a real difference in global health in terms of the achievement of universal health coverage (UHC)—i.e. is ensuring that everyone, everywhere can access quality health services without risk of financial hardship—action is needed at all levels and through a convergence of all types of countries and within the framework of existing multilateral arrangements (Van de Plas et al.). This again may require important changes in the existing global health architecture and in some areas complete transformation.

It is doubtful whether this magnitude of governance innovation can be achieved singularly or mainly through the soft power diplomacy initiated by the RPs. While the current post-2015 international development deliberations have focused on what should be achieved collectively in the next 15 years, more attention needs to be focused on how future global health targets will be attained (Scharferhoff et al. 2015). It is in this regard that the contribution of the RPs to global health policy and domestic health sector development should be framed, if at all these are to be relevant for responding to current and emerging global health challenges. Emerging global health governance agendas of the RPs may therefore require collective recognition, mutual responsibility and shared commitment from other groups interested in transformative development

In order to fulfil the SDGs health targets, the RPs governance innovation strategy should encompass what the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health called a ‘grand convergence’ between poor and rich countries (Lancet Commission 2013). According to the Lancet report, global health convergence will cost US $70 billion per year—which far exceeds current aid flows for health to help finance stronger health sectors. It implies an increasing and evolving role for the RPs as donors and investors in global health to achieve this convergence. This will require investments in ‘global functions’-type assistance (e.g. global public goods like R&D, data needs, pandemic preparedness and containment of anti-microbial resistance)—as well as ‘country-specific functions’-type assistance favoured by RPs. Achieving the SDG health targets would thus require substantial new investments over time, some of which may fall outside the boundaries of soft power diplomacy-type assistance. According to the WHO, investment in global health would need to increase from US$ 134 billion annually in 2017 to $371 billion by 2030 to meet the health targets of the SDGs. If the RPs are to assume a significant role in global health or have a strong influence in the WHO as a global normative agency, they would need to ensure that their soft power diplomacy and international development cooperation programmes contribute to a stronger correlation between more spending and better outcomes. This requires introducing innovations and changes to guide those with responsibility for managing health systems at global, regional and country levels to adopt good governance and prudent management practices based on the principle of value for money.

Today’s global health leaders face the same challenges that informed the construction of health goals and targets of the MDGs in 2000. The expansion of global health initiatives since 2000 has made the global governance system more prone to responding to emergencies than planning to prevent them. There is a need for a more pragmatic mode of cooperation through governance innovation and institutional reform. The WHO, if reformed for example in terms of its funding pattern, management efficiency and governance structure, is in a unique position to support the implementation of the health component of the SDGs 2030 Agenda. Health is an important input to, or impacted by, most of the SDGs targets. Health actors at global, regional, national and sub-national levels are well positioned to contribute to the SDGs health targets. The RPs through soft power development diplomacy need to position themselves in influential ways of organising and prioritising global health efforts and, even prompting a more appropriate global health architecture predicated by global governance innovations, similar to what took place around the turn of the millennium when several new types of global health initiatives appeared on the international scene. But there are key questions still to be addressed: Should global health governance be based on a single lead agency (i.e. the WHO)? How can conflict of interests in decision-making be avoided by the different types of countries among its membership and multiple stakeholders? Should governance arrangements involve distribution of leadership and accountability among stakeholders?

In this context, we need to look at the ability of the RPs in terms of identifying opportunities for governance innovation that facilitate the finding of solutions to today’s global health problems and those emerging in the future. The RPs would need to ensure that their interventions in the global health domain recognise and endorse credible initiatives like the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA), which is a partnership of governments and international organisations aiming to accelerate achievement of the core outbreak preparedness and response capacities required by the IHRs. It is anticipated that the 40th anniversary of the WHO Alma-Ata Declaration (1978) which identified primary health care as the key to the attainment of the goal of ‘Health for All’ will be marked with a new declaration at a global health conference in Astana in October 2018 and be proposed for adoption by the World Health Assembly in May 2019. This will provide another opportunity for the RPs to play a leading role towards a convergence of different interests in helping to shape global health governance for the acceleration of the UHC agenda worldwide.

Current global health governance has clear hierarchical structures—led by the WHO executive committee, with specific roles for national authorities and supported by the ability of the WHO to call on a roster of experts to help in addressing global health challenges. While there is widespread agreement that a WHO influenced strongly by the rich developed nations can no longer be ‘the sole manager of intergovernmental challenges relating to the governance of global health’ (Kickbusch and Szabo 2014), the RPs need to recognise both the possibility and limitation implicit in a need to redistribute the ‘ownership’ of global health governance. Some of the innovative activities and practices of the RPs in the global health field would undoubtedly pose new challenges to the existing structures of global health governance, but the RPs would need to rely on certain fundamentals of these existing structures as enablers in their quest to influence and change the global health architecture. The international development cooperation platform on which the RPs soft power diplomacy is based thus faces the dual challenges of addressing innovation in governance mandate and coexisting with existing multilateralism.

This calls for a delicate balancing act: not only must the RPs continue clamouring for a greater role and aiming to restructure norms, rules and institutions (i.e. ‘rule-makers’), they should also see themselves as ‘rule-takers’ through accommodation of legitimate values rather than seeking revolutionary change in global health agendas. The RPs governance innovation efforts should also incorporate action and policy to promote development effectiveness among their partner developing countries and their leadership. They should encourage them to revive the development effectiveness agenda and broaden the coalition of the local population stakeholders (civil society, private sector, humanitarian organisations, etc.) interested in the ‘how’ of development cooperation. In this manner, the RPs can contribute to a profound change in the global health landscape by suggesting and implementing governance innovations in line with global expectations and to support regional and national development ambitions of developing countries.

Although the RPs role in health cooperation has increased over the past decade, it is still hard to come by systematic data and information required for an accurate assessment of the impact on global health policy and governance. For example, it is also not clear at this point whether the New Development Bank established by the BRICS nations to mobilise resources for infrastructure projects in the emerging and developing economies would also support health sector initiatives and projects directly as important development challenges. The tendency in national development strategy of many developing countries is for health and social development challenges to play second fiddle to economic goals such as infrastructure and industrial development. If the BRICS New Development Bank emerges as a focus for improving population well-being, human development and health, this could indeed be one of the wisest investments by the group. This will serve as a further indication by RPs such as BRICS are ready to channel their ability to more actively translate their declarations and commitments into concrete health policy action.

5 Conclusion

This paper has framed a broad overview of global health policy and architecture from the post-World War II ‘liberal internationalism’ systems which dominated for seven decades to today’s alternative models of a different global order. It has sought to define and elaborate existing and emerging global health challenges in a rapidly changing world order, focusing specifically on the contribution that the Rising Powers (RPs) among the emerging economies can make through soft power diplomacy and new modes of international development cooperation towards addressing these challenges. The analysis of the evolution of the RPs as a ‘change agent’ in the global health scene is illustrated by the efforts of the BRICS group of emerging nations to influence and impact global health and its governance. The rise of BRICS as a major player in global health is an example of mounting efforts by the larger emerging nations towards more equal, sustainable and inclusive structures in many domains of global governance. Through a combination of global action, in the form of soft power development cooperation diplomacy, and governance innovation, the WHO and other global development and humanitarian agencies in the health field are now faced with the challenge of adapting health cooperation to new patterns and structures influenced by the growing power of the RPs in international economic and political environments.

The analysis of the governance innovation efforts of the RPs thus far revealed that there is no single pathway to progress in global health policy towards the ‘ideal’ governance structures. Multiple and flexible pathways of institutional change and governance innovation may be needed to adapt and respond to diverse interests, needs and priorities of global health. While there are good governance justifications today for fundamental shifts in some key structures, institutions, systems and norms that shape global health policy, incremental rather than revolutionary changes may be preferable to bring about desirable transformation in governance structures. A clear challenge facing all involved in global health is to determine how to introduce innovations in the current global health architecture, while operating within the institutional framework of existing multilateral arrangements established and universally accepted for the formulation and execution of international health rules and regulations. This might imply a trade-off between processes that prioritise norms and principles of an established system, on the one hand, and the creativity and innovation needed for development effectiveness on the other.

The RPs influence on global health policy and governance mainly through soft power diplomacy will be grounded in an inherently political space within the framework of the international development landscape. Consequently, the effectiveness of the RPs will not be limited to the logic of medical or technical solutions but will traverse policy pathways influenced by a changing world order that is supported by the realisation of a differentiated and transformative international development agenda. In this regard, the role of the RPs as an agent of change and promoter of health governance innovation can be strategically framed to advance interventions in health as well as other sectors outside health (e.g. security, macroeconomics, human rights) and to appeal to different audiences within specific contexts and timeframes, in order to achieve desired outcomes. In other words, new global health governance models must recognise the realities of global engagement, different interest groups, capabilities and mandates, and multiplicity of stakeholders (multilateral organisations, the state, public health agencies, health professionals, private sector foundations, ‘big pharma’, etc.). In many ways, the RPs engagement in global health governance has only just begun, and it will be some time before its full consequences are revealed and realised. Whatever form it may take, the RPs future on global health governance is likely to be fundamentally different from its past and current structures.

References

Aginam, Obijiofor. 2005. Global health governance: International law and public health in a divided world. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

Anshan, Li. 2011. Chinese Medical Cooperation in Africa. With Special Emphasis on Medical Teams and Anti-Malaria Campaign. Discussion Paper. Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala.

Brautignam, Deborah. 2010. The dragon’s gift: The real story of China in Africa. Oxford: OUP.

Buse, Kent 2004. Global health partnerships: Increasing their impact by improved governance. GHP Study Paper 5. DFID Health Resource Centre: London.

Buse, Kent, and G. Walt. 2000a. Global public–private partnerships: Part I—A new development in health. WHO Bulletin 78 (4): 549–561.

Buse, Kent, and G. Walt. 2000b. Global public–private partnerships: Part II—What are the health issues for global governance? WHO Bulletin 78 (4): 699–709.

Buzan, Barry, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde. 1998. Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner Publications.

Chatham House. 2010. What is next for the G20? Investing in health and development. Conference Summary. 30 June 2010. London.

Cooper, Andrew, and John J. Kirton. 2009. Innovation in global health governance: Critical cases. Farnham: Ashgate.

Cooper, Andrew, John J. Kirton, and Ted Schrecker (eds.). 2007. Governing global health: Challenge, response, innovation. Farnham: Ashgate.

Cornia, Giovanni Andrea. 2001. Globalisation and health: Results and options. WHO Bulletin 79 (9): 834–841.

Cox, Robert, and Timothy J. Sinclair (eds.). 1996. Approaches to world order (Cambridge studies in international relations). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Daschel, Tom, and Bill Frist. 2015. The case for strategic health diplomacy: A study of PEPFAR. Washington, DC: Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC).

Dodgson, Richard, Kelley Lee, and Nick Drager. 2002. Global health governance: A conceptual review. Geneva: WHO and LSHTM.

Enemark, Christian. 2017. Ebola, disease-control, and the security council: From securitization to securing circulation. Journal of Global Security Studies 2 (2): 137–149.

Feldbaum, Harley, Kelley Lee, and Joshua Michaud. 2010. Global health and foreign policy. Epidemiology Review 32: 82–92.

Garrett, L. 2007. The challenge of global health. Foreign Affairs, January/February Issue. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2007-01-01/challenge-global-health.

Gill, Stephen, and Solomon Benatar. 2006. Global health governance and global power: A critical commentary on the lancet-University of Oslo commission report. International Journal of Health Services 46 (2): 346–365.

Harman, Sophie, and Franklyn Lisk (eds.). 2009. Governance of HIV/AIDS: Making participation and accountability work. London: Routledge.

Howard-Jones, Norman. 1975. The scientific background of the international sanitary conferences. Geneva: WHO.

Huang, Yanzhong. 2017. China’s response to the 2014 ebola outbreak in West Africa. Global Challenges 1 (2): 1600001. https://doi.org/10.1002/gch2.201600001.

Ikenberry, G.John. 2018. The end of liberal international order. International Affairs 94 (1): 7–24.

Jahn, Beate. 2018. Liberal internationalism: Historical trajectory and current prospects. International Affairs 94 (1): 43–61.

Kagan, Robert. 2017. The twilight of the liberal world order. 24 January, Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/.

Kahler, Miles. 2013. Rising powers and global governance: Negotiating change in a resilient status quo. International Affairs 89 (3): 711–729.

Keohane, Robert. 2001. Governance in a partially globalised world. American Political Science Review 95 (1): 1–13.

Khoubesserian, Caroline. 2009. Global health initiatives: A health governance response? In Innovation in global health governance: Critical cases, ed. A. Cooper and J. Kirton. Farnham: Ashgate.

Kickbusch, Ilona, Andrew Cassels and Austin Liu. 2016. New directions in governing the global health domain-leadership challenges for WHO. Global Health Centre Working Paper 13, Graduate Institute for International and Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland. http://repository.graduateinstitute.ch/record/294882/files/GHPWP_13_Ilona_2016.pdf.

Kickbusch, Ilona, and Martina Marianna Cassar Szabo. 2014. A new governance space for health. Global Health Action 7 (1): 23507.

Kirton, John. 2015. G20 Governance for a globalised world. Farnham: Ashgate.

Kirton, John, Julia Kulik, and Caroline Bracht. 2014. Generating global health governance through BRICS summitry. Contemporary Politics 20 (2): 146–162.

Kliengibiel, Stephan. 2016. Global problem-solving approaches: The crucial role of China and the group of rising powers. Rising Powers Quarterly 1 (1): 33–41.

Labonté, Ronald, and Michelle L. Gagnon. 2010. Framing health and foreign policy: Lessons for global health diplomacy. Globalisation and Health 6 (14): 1–19.

Lancet Commission on Investing in Health. 2013. Global Health 2035: A world converging within a generation. The Lancet 382 (9908): 1898–1955.

Larionova, Marina, and John J. Kirton (eds.). 2015. The G8–G20 relationship in global governance. Farnham: Ashgate.

Layne, Christopher. 2018. The US-Chinese power shift and the end of the Pax Americana. International Affairs 94 (1): 89–111.

Lee, Kelley, Kent Buse, and Suzanne Fustukian. 2002. Health policy in a globalising world. Cambridge: CUP.

Lin, Vivian and Ilona Kickbush eds. 2017. Progressing the sustainable development goals through health in all policies: Case studies from around the world. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/publications/progressing-sdg-case-studies-2017.pdf.

Lisk, Franklyn. 2010. Global institutions and HIV/AIDS: Responding to an international crisis. London: Routledge.

Mandelbaum, Michael. 2004. The ideas that conquered the world: Peace, democracy, and free markets in the twenty-first century. New York: Public Affairs.

Michaud, Josh, and Jen Kates. 2012. Raising the profile of diplomacy in the US global health response: A backgrounder on global health diplomacy. Policy Brief: Kaiser Family Foundation.

Moran, Michael, and Michael Stevenson. 2013. Illumination and innovation: What philanthropic foundations bring to global health governance. Global Society 27 (2): 117–137.

Norrlof, Carla. 2018. Hegemony and inequality: Trump and the liberal playbook. International Affairs 94 (1): 63–88.

Ruger, Jennifer Prah. 2012. Global health governance as shared health governance. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 66 (7): 653–661.

Ruggie, John Gerard. 1982. International regimes, transactions, and change: Embedded liberalism in the post-war economic order. International Organization 36 (2): 379–415.

Schaferhoff, Marco, Elina Suzuki, Philip Angelides and Steven J. Hoffman. 2015. Rethinking the global health systems. Chatham House Research Paper. https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/field/field_document/20150923GlobalHealthArchitectureSchaferhoffSuzukiAngelidesHoffman.pdf.

Sehovic, Annemarie Bindenagel. 2017. Coordinating global health responses: From HIV/AIDS to Ebola and beyond. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Sekalala, Sharifah. 2017. Soft law and global health problems: Issues from responses to HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Tony. 1994. America’s mission: The United States and the worldwide struggle for democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ullrich, Heidi. 2008. Global health governance and multi-level policy coherence: Can the G8 provide a cure? CIGI Working Paper No. 35. Waterloo, ON: The Centre for International Governance Innovation (GIGI).

West, Darrell M., John Villasenor and Jake Schneider. 2017. Health governance capacity: Enhancing private sector investment in global health. The Brookings Private Sector Global Health Project Working Paper. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/cti_20170329_health_governance_capacity_final.pdf.

WHO. 2014. Health systems governance for universal health coverage. Action Plan, Department of Health Systems Governance and Financing.

Woodward, David, Nick Drager, Robert Beaglehole, and Debra Lipson. 2002. Globalisation and health: A framework for analysis and action. WHO Bulletin 79 (9): 875–881.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lisk, F., Šehović, A.B. Rethinking Global Health Governance in a Changing World Order for Achieving Sustainable Development: The Role and Potential of the ‘Rising Powers’. Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 13, 45–65 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-018-00250-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40647-018-00250-2